Atomic theory has come a long way over the past few thousand years. Beginning in the 5th century BCE with Democritus‘ theory of indivisible “corpuscles” that interact with each other mechanically, then moving onto Dalton’s atomic model in the 18th century, and then maturing in the 20th century with the discovery of subatomic particles and quantum theory, the journey of discovery has been long and winding.

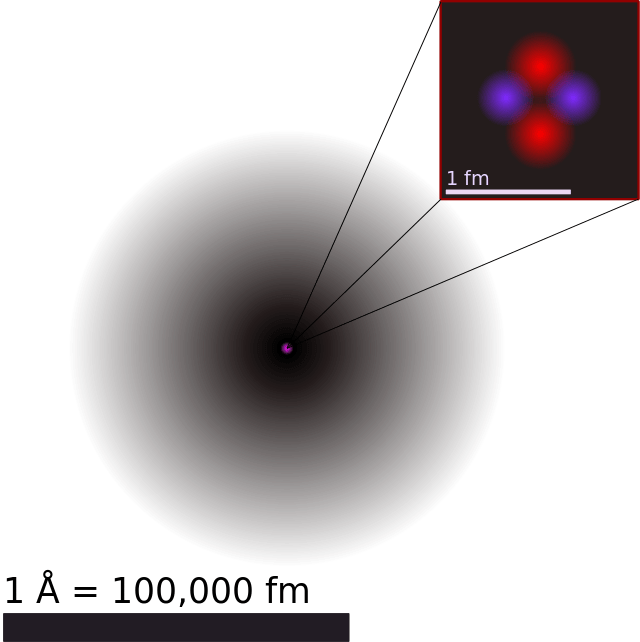

Arguably, one of the most important milestones along the way has been Bohr’ atomic model, which is sometimes referred to as the Rutherford-Bohr atomic model. Proposed by Danish physicist Niels Bohr in 1913, this model depicts the atom as a small, positively charged nucleus surrounded by electrons that travel in circular orbits (defined by their energy levels) around the center.

Atomic Theory to the 19th Century:

The earliest known examples of atomic theory come from ancient Greece and India, where philosophers such as Democritus postulated that all matter was composed of tiny, indivisible and indestructible units. The term “atom” was coined in ancient Greece and gave rise to the school of thought known as “atomism”. However, this theory was more of a philosophical concept than a scientific one.

It was not until the 19th century that the theory of atoms became articulated as a scientific matter, with the first evidence-based experiments being conducted. For example, in the early 1800’s, English scientist John Dalton used the concept of the atom to explain why chemical elements reacted in certain observable and predictable ways. Through a series of experiments involving gases, Dalton went on to develop what is known as Dalton’s Atomic Theory.

This theory expanded on the laws of conversation of mass and definite proportions and came down to five premises: elements, in their purest state, consist of particles called atoms; atoms of a specific element are all the same, down to the very last atom; atoms of different elements can be told apart by their atomic weights; atoms of elements unite to form chemical compounds; atoms can neither be created or destroyed in chemical reaction, only the grouping ever changes.

Discovery of the Electron:

By the late 19th century, scientists also began to theorize that the atom was made up of more than one fundamental unit. However, most scientists ventured that this unit would be the size of the smallest known atom – hydrogen. By the end of the 19th century, this would change drastically, thanks to research conducted by scientists like Sir Joseph John Thomson.

Through a series of experiments using cathode ray tubes (known as the Crookes’ Tube), Thomson observed that cathode rays could be deflected by electric and magnetic fields. He concluded that rather than being composed of light, they were made up of negatively charged particles that were 1ooo times smaller and 1800 times lighter than hydrogen.

This effectively disproved the notion that the hydrogen atom was the smallest unit of matter, and Thompson went further to suggest that atoms were divisible. To explain the overall charge of the atom, which consisted of both positive and negative charges, Thompson proposed a model whereby the negatively charged “corpuscles” were distributed in a uniform sea of positive charge – known as the Plum Pudding Model.

These corpuscles would later be named “electrons”, based on the theoretical particle predicted by Anglo-Irish physicist George Johnstone Stoney in 1874. And from this, the Plum Pudding Model was born, so named because it closely resembled the English desert that consists of plum cake and raisins. The concept was introduced to the world in the March 1904 edition of the UK’s Philosophical Magazine, to wide acclaim.

The Rutherford Model:

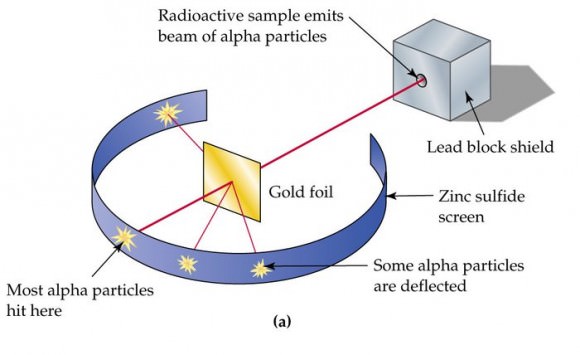

Subsequent experiments revealed a number of scientific problems with the Plum Pudding model. For starters, there was the problem of demonstrating that the atom possessed a uniform positive background charge, which came to be known as the “Thomson Problem”. Five years later, the model would be disproved by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, who conducted a series of experiments using alpha particles and gold foil – aka. the “gold foil experiment.”

In this experiment, Geiger and Marsden measured the scattering pattern of the alpha particles with a fluorescent screen. If Thomson’s model were correct, the alpha particles would pass through the atomic structure of the foil unimpeded. However, they noted instead that while most shot straight through, some of them were scattered in various directions, with some going back in the direction of the source.

Geiger and Marsden concluded that the particles had encountered an electrostatic force far greater than that allowed for by Thomson’s model. Since alpha particles are just helium nuclei (which are positively charged) this implied that the positive charge in the atom was not widely dispersed, but concentrated in a tiny volume. In addition, the fact that those particles that were not deflected passed through unimpeded meant that these positive spaces were separated by vast gulfs of empty space.

By 1911, physicist Ernest Rutherford interpreted the Geiger-Marsden experiments and rejected Thomson’s model of the atom. Instead, he proposed a model where the atom consisted of mostly empty space, with all its positive charge concentrated in its center in a very tiny volume, that was surrounded by a cloud of electrons. This came to be known as the Rutherford Model of the atom.

The Bohr Model:

Subsequent experiments by Antonius Van den Broek and Niels Bohr refined the model further. While Van den Broek suggested that the atomic number of an element is very similar to its nuclear charge, the latter proposed a Solar-System-like model of the atom, where a nucleus contains the atomic number of positive charge and is surrounded by an equal number of electrons in orbital shells (aka. the Bohr Model).

In addition, Bohr’s model refined certain elements of the Rutherford model that were problematic. These included the problems arising from classical mechanics, which predicted that electrons would release electromagnetic radiation while orbiting a nucleus. Because of the loss in energy, the electron should have rapidly spiraled inwards and collapsed into the nucleus. In short, this atomic model implied that all atoms were unstable.

The model also predicted that as electrons spiraled inward, their emission would rapidly increase in frequency as the orbit got smaller and faster. However, experiments with electric discharges in the late 19th century showed that atoms only emit electromagnetic energy at certain discrete frequencies.

Bohr resolved this by proposing that electrons orbiting the nucleus in ways that were consistent with Planck’s quantum theory of radiation. In this model, electrons can occupy only certain allowed orbitals with a specific energy. Furthermore, they can only gain and lose energy by jumping from one allowed orbit to another, absorbing or emitting electromagnetic radiation in the process.

These orbits were associated with definite energies, which he referred to as energy shells or energy levels. In other words, the energy of an electron inside an atom is not continuous, but “quantized”. These levels are thus labeled with the quantum number n (n=1, 2, 3, etc.) which he claimed could be determined using the Ryberg formula – a rule formulated in 1888 by Swedish physicist Johannes Ryberg to describe the wavelengths of spectral lines of many chemical elements.

Influence of the Bohr Model:

While Bohr’s model did prove to be groundbreaking in some respects – merging Ryberg’s constant and Planck’s constant (aka. quantum theory) with the Rutherford Model – it did suffer from some flaws which later experiments would illustrate. For starters, it assumed that electrons have both a known radius and orbit, something that Werner Heisenberg would disprove a decade later with his Uncertainty Principle.

In addition, while it was useful for predicting the behavior of electrons in hydrogen atoms, Bohr’s model was not particularly useful in predicting the spectra of larger atoms. In these cases, where atoms have multiple electrons, the energy levels were not consistent with what Bohr predicted. The model also didn’t work with neutral helium atoms.

The Bohr model also could not account for the Zeeman Effect, a phenomenon noted by Dutch physicists Pieter Zeeman in 1902, where spectral lines are split into two or more in the presence of an external, static magnetic field. Because of this, several refinements were attempted with Bohr’s atomic model, but these too proved to be problematic.

In the end, this would lead to Bohr’s model being superseded by quantum theory – consistent with the work of Heisenberg and Erwin Schrodinger. Nevertheless, Bohr’s model remains useful as an instructional tool for introducing students to more modern theories – such as quantum mechanics and the valence shell atomic model.

It would also prove to be a major milestone in the development of the Standard Model of particle physics, a model characterized by “electron clouds“, elementary particles, and uncertainty.

We have written many interesting articles about atomic theory here at Universe Today. Here’s John Dalton’s Atomic Model, What is the Plum Pudding Model, What is the Electron Cloud Model?, Who Was Democritus?, and What are the Parts of the Atom?

Astronomy Cast also has some episodes on the subject: Episode 138: Quantum Mechanics, Episode 139: Energy Levels and Spectra, Episode 378: Rutherford and Atoms and Episode 392: The Standard Model – Intro.

Sources:

- Niels Bohr (1913) “On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part I”

- Niels Bohr (1913) “On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules, Part II Systems Containing Only a Single Nucleus”

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Borh Atomic Model

- Hyperphysics – Bohr Model

- University of Tennessee, Knoxville – The Borh Model

- University of Toronto – The Bohr Model of the Atom

- NASA – Imagine the Universe – Background: Atoms and Light Energy

- About Education – Bohr Model of the Atom