On May 10th, 2024, people across North America were treated to a rare celestial event: an aurora visible from the Eastern Seabord to the Southern United States. This particular sighting of the Northern Lights (aka. Aurora Borealis) coincided with the most extreme geomagnetic storm since 2003 and the 27th strongest solar flare ever recorded. This led to the dazzling display that was visible to residents all across North America but was also detected by some of Ocean Networks Canada‘s (ONC) undersea sensors at depths of almost three kilometers.

Continue reading “That Recent Solar Storm Was Detected Almost Three Kilometers Under the Ocean”What a Weekend! Spectacular Aurora Photos from Around the World

“A dream come true.”

“I never expected this!”

“The most amazing light show I’ve ever seen in my life!”

“Once in a lifetime!”

“No doubt, this weekend will be remembered as ‘that weekend.’”

That’s how people described their views of the Aurora borealis this weekend, which put on a breathtaking celestial show around the world, and at lower latitudes than usual. This allowed hundreds of millions of people to see the northern lights for the first time in their lives. People as far south as Arizona and Florida in the US and France, Germany and Poland in Europe got the views of their life as a series of intense solar storms – the most powerful in more than 20 years – impacted Earth’s atmosphere starting Friday and through the weekend.

Continue reading “What a Weekend! Spectacular Aurora Photos from Around the World”If You’ve Never Seen An Aurora Before, This Might Be Your Chance!

Tonight and the rest of the weekend could be your best chance ever to see the aurora.

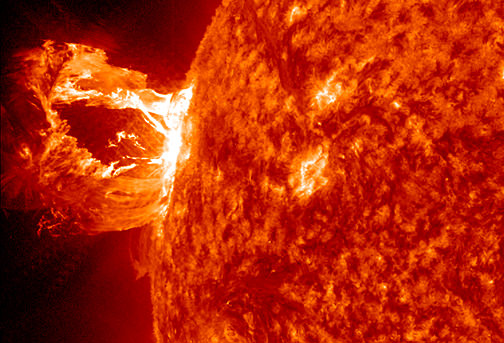

The Sun has been extremely active lately as it heads towards solar maximum. A giant Earth-facing sunspot group named AR3664 has been visible, and according to Spaceweather.com, the first of an unbelievable SIX coronal mass ejections were hurled our way from that active region, and is now hitting our planet’s magnetic field.

Solar experts predict that people in the US as far south as Alabama and Northern California could be treated to seeing the northern lights during this weekend. For those of you in northern Europe, you could also be in for some aurora excitement. Check the Space Weather Prediction Center’s 30-minute Aurora Forecast for the latest information.

If the weather conditions are right in your area, you might hit the aurora jackpot. See a map with predictions, below.

Continue reading “If You’ve Never Seen An Aurora Before, This Might Be Your Chance!”The Sun Just Blasted its Strongest Flare in 6 Years. Get Ready for Auroras

While many of us were celebrating the end of 2023 and the coming of 2024, the Sun was having its own celebration blasting an X5.0 flare from sunspot region 3536. Records show this to be the most powerful flare seen since 10 September 2017 when an X8.2 flare erupted. The flare is expected to arrive around Jan 2 – EEK that’s today! Get your aurora watching kit out!

Continue reading “The Sun Just Blasted its Strongest Flare in 6 Years. Get Ready for Auroras”An 1874 Citizen Science Project Studying the Aurora Borealis Helped Inspire Time Zones

For millennia, humans have gazed at the northern lights with wonder, pondering their nature and source. Even today, these once mysterious phenomena still evoke awe, though we understand them a little better now. Still, most of our knowledge about the northern lights has come recently, in the last century or two. Astronomers and meteorologists of the 1800s worked for years to understand the aurora, wondering if they were a feature of Earth’s atmospheric weather, of outer space, or, perhaps, something that straddled the boundary in-between. This centuries-old attempt to understand the northern lights was an immense, international-scale project, and, through fortunate happenstance, it even helped inspire one of the underlying foundations of modern society – time zones.

Continue reading “An 1874 Citizen Science Project Studying the Aurora Borealis Helped Inspire Time Zones”That New Kind of Aurora Called “Steve”? Turns Out, it Isn’t an Aurora at All

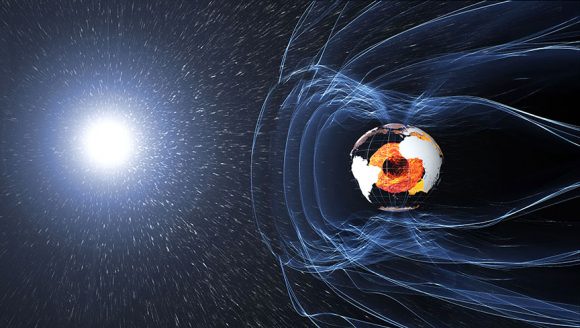

Since time immemorial, people living in the Arctic Circle or the southern tip of Chile have looked up at the night sky and been dazzled by the sight of the auroras. Known as the Aurora Borealis in the north and Aurora Australis in the south (the “Northern Lights” and “Southern Lights”, respectively) these dazzling displays are the result of interactions in the ionosphere between charged solar particles and the Earth’s magnetic field.

However, in recent decades, amateur photographers began capturing photos of what appeared to be a new type of aurora – known as STEVE. In 2016, it was brought to the attention of scientists, who began trying to explain what accounted for the strange ribbons of purple and white light in the night sky. According to a new study, STEVE is not an aurora at all, but an entirely new celestial phenomenon.

The study recently appeared in the Geophysical Research Letters under the title “On the Origin of STEVE: Particle Precipitation or Ionospheric Skyglow?“. The study was conducted by a team of researchers from the Department of Physics and Astronomy from the University of Calgary, which was led by Beatriz Gallardo-Lacourt (a postdoctoral associate), and included Yukitoshi Nishimura – an assistant researcher of the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of California.

STEVE first became known to scientists thanks to the efforts of the Alberta Aurora Chasers (AAC), who occasionally noticed these bright, thin streams of white and purple light running from east to west in the night sky when photographing the aurora. Unlike auroras, which are visible whenever viewing conditions are right, STEVE was only visible a few times a year and could only be seen at high latitudes.

Initially, the photographers thought the light ribbons were the result of excited protons, but these fall outside the range of wavelengths that normal cameras can see and require special equipment to image. The AAC eventually named the light ribbons “Steve” – a reference to the 2006 film Over the Hedge. By 2016, Steve was brought to the attention of scientists, who turned the name into a backronym for Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement.

For their study, the research team analyzed a STEVE event that took place on March 28th, 2008, to see if it was produced in a similar fashion to an aurora. To this end, they considered previous research that was conducted using satellites and ground-based observatories, which included the first study on STEVE (published in March of 2018) conducted by a team of NASA-led scientists (of which Gallardo-Lacourt was a co-author).

This study indicated the presence of a stream of fast-moving ions and super-hot electrons passing through the ionosphere where STEVE was observed. While the research team suspected the two were connected, they could not conclusively state that the ions and electrons were responsible for producing it. Building on this, Gallardo-Lacourt and her colleagues analyzed the STEVE event that took place in March of 2008.

They began by using images from ground-based cameras that record auroras over North America, which they then combined with data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration‘s (NOAA) Polar Orbiting Environmental Satellite 17 (POES-17). This satellite, which can measure the precipitation of charged particles into the ionosphere, was passing directly over the ground-based cameras during the STEVE event.

What they found was that the POES-17 satellite detected no charged particles raining down on the ionosphere during the event. This means that STEVE is not likely to be caused by the same mechanism as an aurora, and is therefore an entirely new type of optical phenomenon – which the team refer to as “skyglow”. As Gallardo-Lacourt explained in an AGU press release:

“Our main conclusion is that STEVE is not an aurora. So right now, we know very little about it. And that’s the cool thing, because this has been known by photographers for decades. But for the scientists, it’s completely unknown.”

Looking ahead, Galladro-Lacourt and her colleagues seek to test the conclusions of the NASA-led study. In short, they want to find out whether the streams of fast ions and hot electrons that were detected in the ionosphere are responsible for STEVE, or if the light is being produced higher up in the atmosphere. One thing is for certain though; for aurora chasers, evening sky-watching has become more interesting!

Further Reading: AGU

What Was the Carrington Event?

Isn’t modern society great? With all this technology surrounding us in all directions. It’s like a cocoon of sweet, fluffy silicon. There are chips in my fitness tracker, my bluetooth headset, mobile phone, car keys and that’s just on my body.

At all times in the Cain household, there dozens of internet devices connected to my wifi router. I’m not sure how we got to the point, but there’s one thing I know for sure, more is better. If I could use two smartphones at the same time, I totally would.

And I’m sure you agree, that without all this technology, life would be a pale shadow of its current glory. Without these devices, we’d have to actually interact with each other. Maybe enjoy the beauty of nature, or something boring like that.

It turns out, that terrible burning orb in the sky, the Sun, is fully willing and capable of bricking our precious technology. It’s done so in the past, and it’s likely to take a swipe at us in the future.

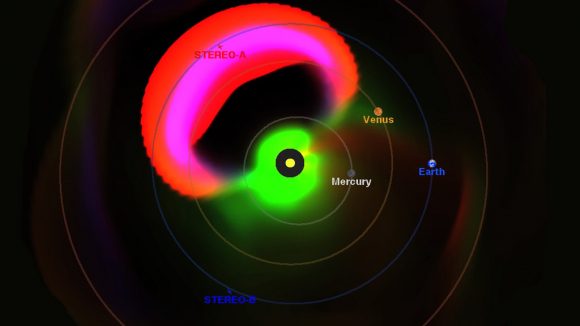

I’m talking about solar storms, of course, tremendous blasts of particles and radiation from the Sun which can interact with the Earth’s magnetosphere and overwhelm anything with a wire.

In fact, we got a sneak preview of this back in 1859, when a massive solar storm engulfed the Earth and ruined our old timey technology. It was known as the Carrington Event.

Follow your imagination back to Thursday, September 1st, 1859. This was squarely in the middle of the Victorian age.

And not the awesome, fictional Steampunk Victorian age where spectacled gentleman and ladies of adventure plied the skies in their steam-powered brass dirigibles.

No, it was the regular crappy Victorian age of cholera and child labor. Technology was making huge leaps and bounds, however, and the first telegraph lines and electrical grids were getting laid down.

Imagine a really primitive version of today’s electrical grid and internet.

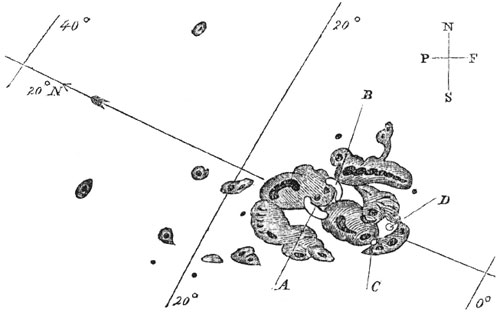

On that fateful morning, the British astronomer Richard Carrington turned his solar telescope to the Sun, and was amazed at the huge sunspot complex staring back at him. So impressed that he drew this picture of it.

While he was observing the sunspot, Carrington noticed it flash brightly, right in his telescope, becoming a large kidney-shaped bright white flare.

Carrington realized he was seeing unprecedented activity on the surface of the Sun. Within a minute, the activity died down and faded away.

And then about 5 minutes later. Aurora activity erupted across the entire planet. We’re not talking about those rare Northern Lights enjoyed by the Alaskans, Canadians and Northern Europeans in the audience. We’re talking about everyone, everywhere on Earth. Even in the tropics.

In fact, the brilliant auroras were so bright you could read a book to them.

The beautiful night time auroras was just one effect from the monster solar flare. The other impact was that telegraph lines and electrical grids were overwhelmed by the electricity pushed through their wires. Operators got electrical shocks from their telegraph machines, and the telegraph paper lit on fire.

What happened? The most powerful solar flare ever observed is what happened.

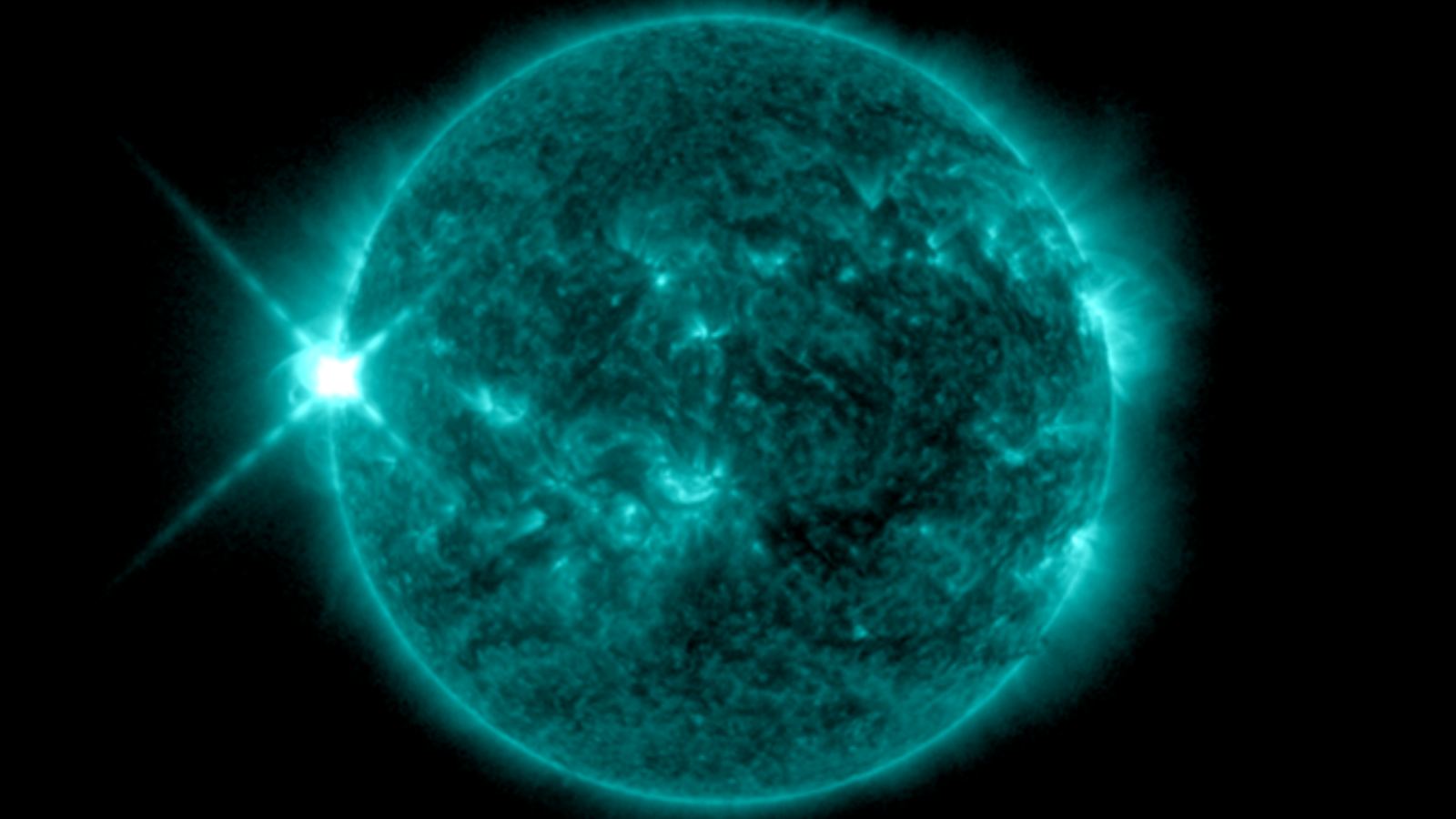

A solar flare occurs because the Sun’s magnetic field lines can get tangled up in the solar atmosphere. In a moment, the magnetic fields reorganize themselves, and a huge wave of particles and radiation is released.

Flares happen in three stages. First, you get the precursor stage, with a blast of soft X-ray radiation. This is followed by the impulsive stage, where protons and electrons are accelerated off the surface of the Sun. And finally, the decay stage, with another burp of X-rays as the flare dies down.

These stages can happen in just a few seconds or drag out over an hour.

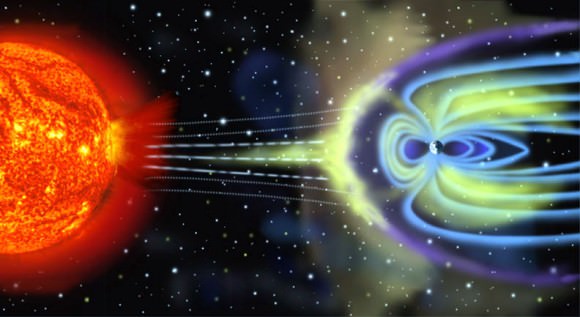

Remember those particles hurled off into space? They take several hours or a few days to reach Earth and interact with our planet’s protective magnetosphere, and then we get to see beautiful auroras in the sky.

This geomagnetic storm causes the Earth’s magnetosphere to jiggle around, which drives charges through wires back and forth, burning out circuits, killing satellites, overloading electrical grids.

Back in 1859, this wasn’t a huge deal, when our quaint technology hadn’t progressed beyond the occasional telegraph tower.

Today, our entire civilization depends on wires. There are wires in the hundreds of satellites flying overhead that we depend on for communications and navigation. Our homes and businesses are connected by an enormous electrical grid. Airplanes, cars, smartphones, this camera I’m using.

Everything is electronic, or controlled by electronics.

Think it can’t happen? We got a sneak preview back in March, 1989 when a much smaller geomagnetic storm crashed into the Earth. People as far south as Florida and Cuba could see auroras in the sky, while North America’s entire interconnected electrical grid groaned under the strain.

The Canadian province of Quebec’s electrical grid wasn’t able to handle the load and went entirely offline. For 12 hours, in the freezing Quebec winter, almost the entire province was without power. I’m telling you, that place gets cold, so this was really bad timing.

Satellites went offline, including NASA’s TDRS-1 communication satellite, which suffered 250 separate glitches during the storm.

And on July 23, 2012, a Carrington-class solar superstorm blasted off the Sun, and off into space. Fortunately, it missed the Earth, and we were spared the mayhem.

If a solar storm of that magnitude did strike the Earth, the cleanup might cost $2 trillion, according to a study by the National Academy of Sciences.

It’s been 160 years since the Carrington Event, and according to ice core samples, this was the most powerful solar flare over the last 500 years or so. Solar astronomers estimate solar storms like this happen twice a millennium, which means we’re not likely to experience another one in our lifetimes.

But if we do, it’ll cause worldwide destruction of technology and anyone reliant on it. You might want to have a contingency plan with some topic starters when you can’t access the internet for a few days. Locate nearby interesting nature spots to explore and enjoy while you wait for our technological civilization to be rebuilt.

Have you ever seen an aurora in your lifetime? Give me the details of your experience in the comments.

How Can You see the Northern Lights?

The Northern Lights have fascinated human beings for millennia. In fact, their existence has informed the mythology of many cultures, including the Inuit, Northern Cree, and ancient Norse. They were also a source of intense fascination for the ancient Greeks and Romans, and were seen as a sign from God by medieval Europeans.

Thanks to the birth of modern astronomy, we now know what causes both the Aurora Borealis and its southern sibling – Aurora Australis. Nevertheless, they remain the subject of intense fascination, scientific research, and are a major tourist draw. For those who live north of 60° latitude, this fantastic light show is also a regular occurrence.

Causes:

Aurora Borealis (and Australis) is caused by interactions between energetic particles from the Sun and the Earth’s magnetic field. The invisible field lines of Earth’s magnetoshere travel from the Earth’s northern magnetic pole to its southern magnetic pole. When charged particles reach the magnetic field, they are deflected, creating a “bow shock” (so-named because of its apparent shape) around Earth.

However, Earth’s magnetic field is weaker at the poles, and some particles are therefore able to enter the Earth’s atmosphere and collide with gas particles in these regions. These collisions emit light that we perceive as wavy and dancing, and are generally a pale, yellowish-green in color.

The variations in color are due to the type of gas particles that are colliding. The common yellowish-green is produced by oxygen molecules located about 100 km (60 miles) above the Earth, whereas high-altitude oxygen – at heights of up to 320 km (200 miles) – produce all-red auroras. Meanwhile, interactions between charged particles and nitrogen will produces blue or purplish-red auroras.

Variability:

The visibility of the northern (and southern) lights depends on a lot of factors, much like any other type of meteorological activity. Though they are generally visible in the far northern and southern regions of the globe, there have been instances in the past where the lights were visible as close to the equator as Mexico.

In places like Alaska, Norther Canada, Norway and Siberia, the northern lights are often seen every night of the week in the winter. Though they occur year-round, they are only visible when it is rather dark out. Hence why they are more discernible during the months where the nights are longer.

Because they depend on the solar wind, auroras are more plentiful during peak periods of activity in the Solar Cycle. This cycle takes places every 11 years, and is marked by the increase and decrease of sunspots on the sun’s surface. The greatest number of sunspots in any given solar cycle is designated as a “Solar Maximum“, whereas the lowest number is a “Solar Minimum.”

A Solar Maximum also accords with bright regions appearing in the Sun’s corona, which are rooted in the lower sunspots. Scientists track these active regions since they are often the origin of eruptions on the Sun, such as solar flares or coronal mass ejections.

The most recent solar minimum occurred in 2008. As of January 2010, the Sun’s surface began to increase in activity, which began with the release of a lower-intensity M-class flare. The Sun continued to get more active, culminating in a Solar Maximum by the summer of 2013.

Locations for Viewing:

The ideal places to view the Northern Lights are naturally located in geographical regions north of 60° latitude. These include northern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Scandinavia, Alaska, and Northern Russia. Many organizations maintain websites dedicated to tracking optimal viewing conditions.

For instance, the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska Fairbanks maintains the Aurora Forecast. This site is regularly updated to let residents know when auroral activity is high, and how far south it will extend. Typically, residents who live in central or northern Alaska (from Fairbanks to Barrow) have a better chance than those living in the south (Anchorage to Juneau).

In Northern Canada, auroras are often spotted from the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Northern Quebec. However, they are sometimes seen from locations like Dawson Creek, BC; Fort McMurry, Alberta; northern Saskatchewan and the town of Moose Factory by James Bay, Ontario. For information, check out Canadian Geographic Magazine’s “Northern Lights Across Canada“.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency also provides 30 minute forecasts on auroras through their Space Weather Prediction Center. And then there’s Aurora Alert, an Android App that allows you to get regular updates on when and where an aurora will be visible in your region.

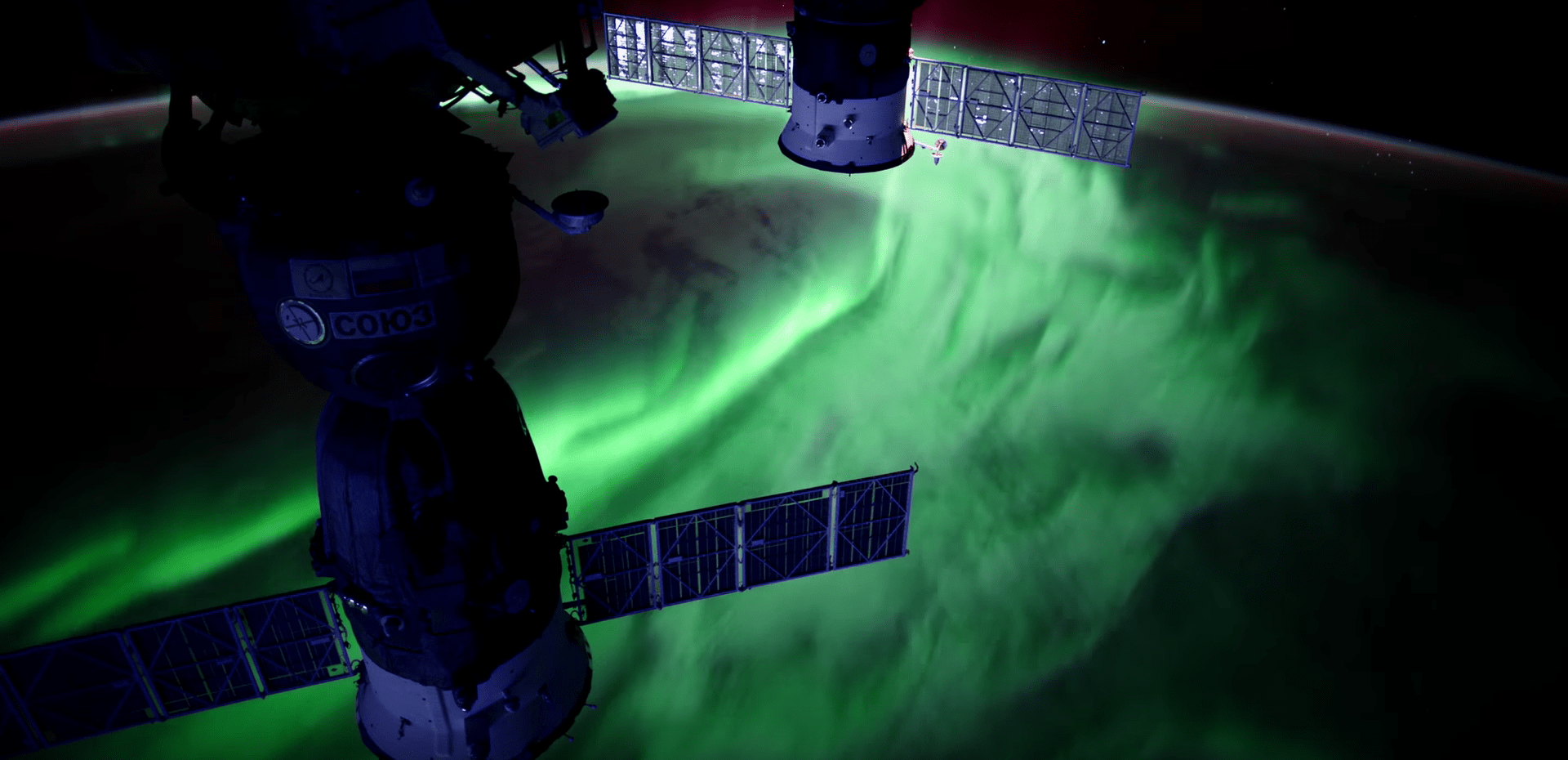

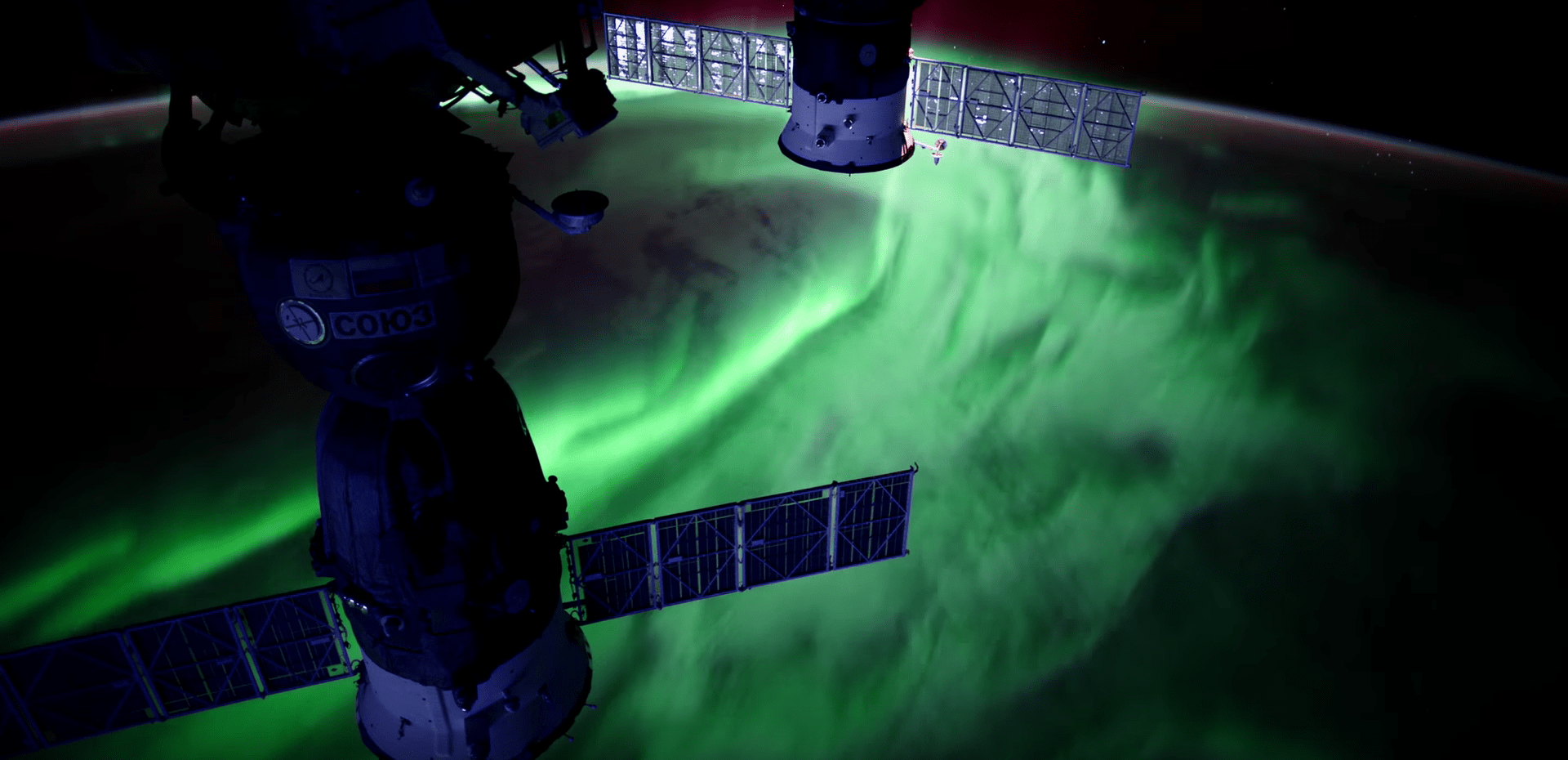

Understanding the scientific cause of auroras has not made them any less awe-inspiring or wondrous. Every year, countless people venture to locations where they can be seen. And for those serving aboard the ISS, they got the best seat in the house!

Speaking of which, be sure to check out this stunning NASA video which shows the Northern Lights being viewed from the ISS:

We have written many interesting articles about Auroras here at Universe Today. Here’s The Northern and Southern Lights – What is an Aurora?, What is the Aurora Borealis?, What is the Aurora Australis?, What Causes the Northern Lights?, How Does the Aurora Borealis Form?, and Watch Fast and Furious All-sky Aurora Filmed in Real Time.

For more information, visit the THEMIS website – a NASA mission that is currently studying space weather in great detail. The Space Weather Center has information on the solar wind and how it causes aurorae.

Astronomy Cast also has episodes on the subject, like Episode 42: Magnetism Everywhere.

Sources:

Stunning Auroras From the Space Station in Ultra HD – Videos

Stunning high definition views of Earth’s auroras and dancing lights as seen from space like never before have just been released by NASA in the form of ultra-high definition videos (4K) captured from the International Space Station (ISS).

Whether seen from the Earth or space, auroras are endlessly fascinating and appreciated by everyone young and old and from all walks of life.

The spectacular video compilation, shown below, was created from time-lapses shot from ultra-high definition cameras mounted at several locations on the ISS.

It includes HD view of both the Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis phenomena seen over the northern and southern hemispheres.

The video begins with an incredible time lapse sequence of an astronaut cranking open the covers off the domed cupola – everyone’s favorite locale. Along the way it also shows views taken from inside the cupola.

The cupola also houses the robotics works station for capturing visiting vehicles like the recently arrived unmanned SpaceX Dragon and Orbital ATK Cygnus cargo freighters carrying science experiments and crew supplies.

The video was produced by Harmonic exclusively for NASA TV UHD;

Video caption: Ultra-high definition (4K) time-lapses of both the Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis phenomena shot from the International Space Station (ISS). Credit: NASA

The video segue ways into multi hued auroral views including Russian Soyuz and Progress capsules, the stations spinning solar panels, truss and robotic arm, flying over Europe, North America, Africa, the Middle East, star fields, the setting sun and moon, and much more.

Auroral phenomena occur when electrically charged electrons and protons in the Earth’s magnetic field collide with neutral atoms in the upper atmosphere.

“The dancing lights of the aurora provide a spectacular show for those on the ground, but also capture the imaginations of scientists who study the aurora and the complex processes that create them,” as described by NASA.

Here’s another musical version to enjoy:

The ISS orbits some 250 miles (400 kilometers) overhead with a multinational crew of six astronauts and cosmonauts living and working aboard.

The current Expedition 47 crew is comprised of Jeff Williams and Tim Kopra of NASA, Tim Peake of ESA (European Space Agency) and cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko, Alexey Ovchinin and Oleg Skripochka of Roscosmos.

Some of the imagery was shot by recent prior space station crew members.

Here is a recent aurora image taken by flight engineer Tim Peake of ESA as the ISS passed through on Feb. 23, 2016.

“The @Space_Station just passed straight through a thick green fog of #aurora…eerie but very beautiful,” Peake wrote on social media.

A new room was just added to the ISS last weekend when the BEAM experimental expandable habitat was attached to a port on the Tranquility module using the robotic arm.

BEAM was carried to the ISS inside the unpressurized trunk section of the recently arrived SpaceX Dragon cargo ship.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Venus Compared to Earth

Venus is often referred to as “Earth’s Twin” (or “sister planet”), and for good reason. Despite some rather glaring differences, not the least of which is their vastly different atmospheres, there are enough similarities between Earth and Venus that many scientists consider the two to be closely related. In short, they are believed to have been very similar early in their existence, but then evolved in different directions.

Earth and Venus are both terrestrial planets that are located within the Sun’s Habitable Zone (aka. “Goldilocks Zone”) and have similar sizes and compositions. Beyond that, however, they have little in common. Let’s go over all their characteristics, one by one, so we can in what ways they are different and what ways they are similar.