Ever since the 16th century when Nicolaus Copernicus demonstrated that the Earth revolved around in the Sun, scientists have worked tirelessly to understand the relationship in mathematical terms. If this bright celestial body – upon which depends the seasons, the diurnal cycle, and all life on Earth – does not revolve around us, then what exactly is the nature of our orbit around it?

For several centuries, astronomers have applied the scientific method to answer this question, and have determined that the Earth’s orbit around the Sun has many fascinating characteristics. And what they have found has helped us to understanding why we measure time the way we do.

Orbital Characteristics:

First of all, the speed of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun is 108,000 km/h, which means that our planet travels 940 million km during a single orbit. The Earth completes one orbit every 365.242199 mean solar days, a fact which goes a long way towards explaining why need an extra calendar day every four years (aka. during a leap year).

The planet’s distance from the Sun varies as it orbits. In fact, the Earth is never the same distance from the Sun from day to day. When the Earth is closest to the Sun, it is said to be at perihelion. This occurs around January 3rd each year, when the Earth is at a distance of about 147,098,074 km.

The average distance of the Earth from the Sun is about 149.6 million km, which is also referred to as one astronomical unit (AU). When it is at its farthest distance from the Sun, Earth is said to be at aphelion – which happens around July 4th where the Earth reaches a distance of about 152,097,701 km.

And those of you in the northern hemisphere will notice that “warm” or “cold” weather does not coincide with how close the Earth is to the Sun. That is determined by axial tilt (see below).

Elliptical Orbit:

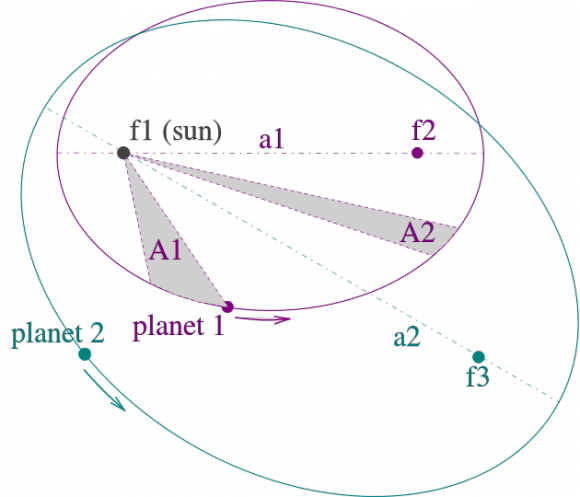

Next, there is the nature of the Earth’s orbit. Rather than being a perfect circle, the Earth moves around the Sun in an extended circular or oval pattern. This is what is known as an “elliptical” orbit. This orbital pattern was first described by Johannes Kepler, a German mathematician and astronomer, in his seminal work Astronomia nova (New Astronomy).

After measuring the orbits of the Earth and Mars, he noticed that at times, the orbits of both planets appeared to be speeding up or slowing down. This coincided directly with the planets’ aphelion and perihelion, meaning that the planets’ distance from the Sun bore a direct relationship to the speed of their orbits. It also meant that both Earth and Mars did not orbit the Sun in perfectly circular patterns.

In describing the nature of elliptical orbits, scientists use a factor known as “eccentricity”, which is expressed in the form of a number between zero and one. If a planet’s eccentricity is close to zero, then the ellipse is nearly a circle. If it is close to one, the ellipse is long and slender.

Earth’s orbit has an eccentricity of less than 0.02, which means that it is very close to being circular. That is why the difference between the Earth’s distance from the Sun at perihelion and aphelion is very little – less than 5 million km.

Seasonal Change:

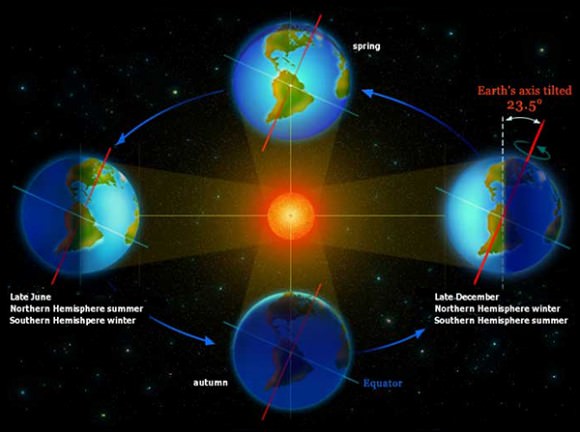

Third, there is the role Earth’s orbit plays in the seasons, which we referred to above. The four seasons are determined by the fact that the Earth is tilted 23.4° on its vertical axis, which is referred to as “axial tilt.” This quirk in our orbit determines the solstices – the point in the orbit of maximum axial tilt toward or away from the Sun – and the equinoxes, when the direction of the tilt and the direction to the Sun are perpendicular.

In short, when the northern hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun, it experiences winter while the southern hemisphere experiences summer. Six months later, when the northern hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun, the seasonal order is reversed.

In the northern hemisphere, winter solstice occurs around December 21st, summer solstice is near June 21st, spring equinox is around March 20th and autumnal equinox is about September 23rd. The axial tilt in the southern hemisphere is exactly the opposite of the direction in the northern hemisphere. Thus the seasonal effects in the south are reversed.

While it is true that Earth does have a perihelion, or point at which it is closest to the sun, and an aphelion, its farthest point from the Sun, the difference between these distances is too minimal to have any significant impact on the Earth’s seasons and climate.

Lagrange Points:

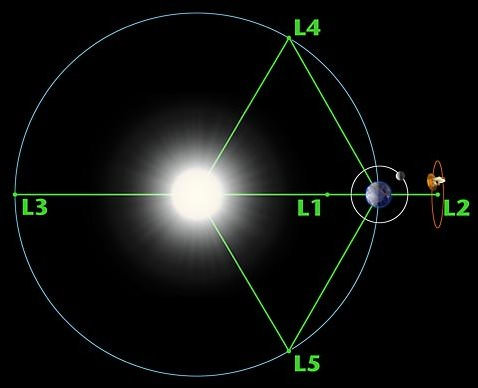

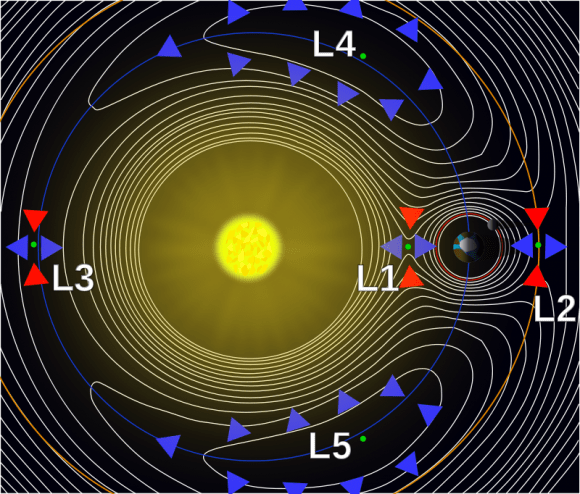

Another interesting characteristic of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun has to do with Lagrange Points. These are the five positions in Earth’s orbital configuration around the Sun where where the combined gravitational pull of the Earth and the Sun provides precisely the centripetal force required to orbit with them.

The five Lagrange Points between the Earth are labelled (somewhat unimaginatively) L1 to L5. L1, L2, and L3 sit along a straight line that goes through the Earth and Sun. L1 sits between them, L3 is on the opposite side of the Sun from the Earth, and L2 is on the opposite side of the Earth from L1. These three Lagrange points are unstable, which means that a satellite placed at any one of them will move off course if disturbed in the slightest.

The L4 and L5 points lie at the tips of the two equilateral triangles where the Sun and Earth constitute the two lower points. These points liem along along Earth’s orbit, with L4 60° behind it and L5 60° ahead. These two Lagrange Points are stable, hence why they are popular destinations for satellites and space telescopes.

The study of Earth’s orbit around the Sun has taught scientists much about other planets as well. Knowing where a planet sits in relation to its parent star, its orbital period, its axial tilt, and a host of other factors are all central to determining whether or not life may exist on one, and whether or not human beings could one day live there.

We have written many interesting articles about the Earth’s orbit here at Universe Today. Here’s 10 Interesting Facts About Earth, How Far is Earth from the Sun?, What is the Rotation of the Earth?, Why are there Seasons?, and What is Earth’s Axial Tilt?

For more information, check out this article on NASA- Window’s to the Universe article on elliptical orbits or check out NASA’s Earth: Overview.

Astronomy Cast also espidoes that are relevant to the subject. Here’s BQuestions Show: Black black holes, Unbalancing the Earth, and Space Pollution.

Sources: