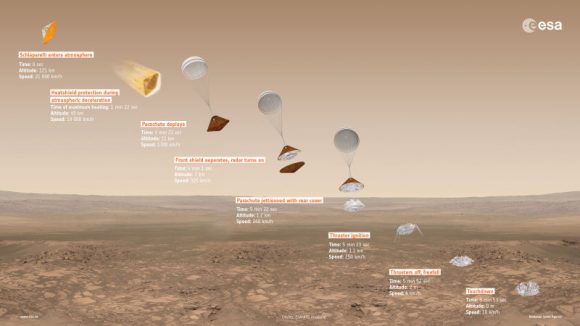

Last week, ESA’s Schiaparelli lander smashed onto the surface of Mars. Apparently its descent thrusters shut off early, and instead of gently landing on the surface, it hit hard, going 300 km/h, creating a 15-meter crater on the surface of Mars.

Fortunately, the orbiter part of ExoMars mission made it safely to Mars, and will now start gathering data about the presence of methane in the Martian atmosphere. If everything goes well, this might give us compelling evidence there’s active life on Mars, right now.

It’s a shame that the lander portion of the mission crashed on the surface of Mars, but it’s certainly not surprising. In fact, so many spacecraft have gone to the galactic graveyard trying to reach Mars that normally rational scientists turn downright superstitious about the place. They call it the Mars Curse, or the Great Galactic Ghoul.

Mars eats spacecraft for breakfast. It’s not picky. It’ll eat orbiters, landers, even gentle and harmless flybys. Sometimes it kills them before they’ve even left Earth orbit.

At the time I’m writing this article in late October, 2016, Earthlings have sent a total of 55 robotic missions to Mars. Did you realize we’ve tried to hurl that much computing metal towards the Red Planet? 11 flybys, 23 orbiters, 15 landers and 6 rovers.

How’s our average? Terrible. Of all these spacecraft, only 53% have arrived safe and sound at Mars, to carry out their scientific mission. Half of all missions have failed.

Let me give you a bunch of examples.

In the early 1960s, the Soviets tried to capture the space exploration high ground to send missions to Mars. They started with the Mars 1M probes. They tried launching two of them in 1960, but neither even made it to space. Another in 1962 was destroyed too.

They got close with Mars 1 in 1962, but it failed before it reached the planet, and Mars 2MV didn’t even leave the Earth’s orbit.

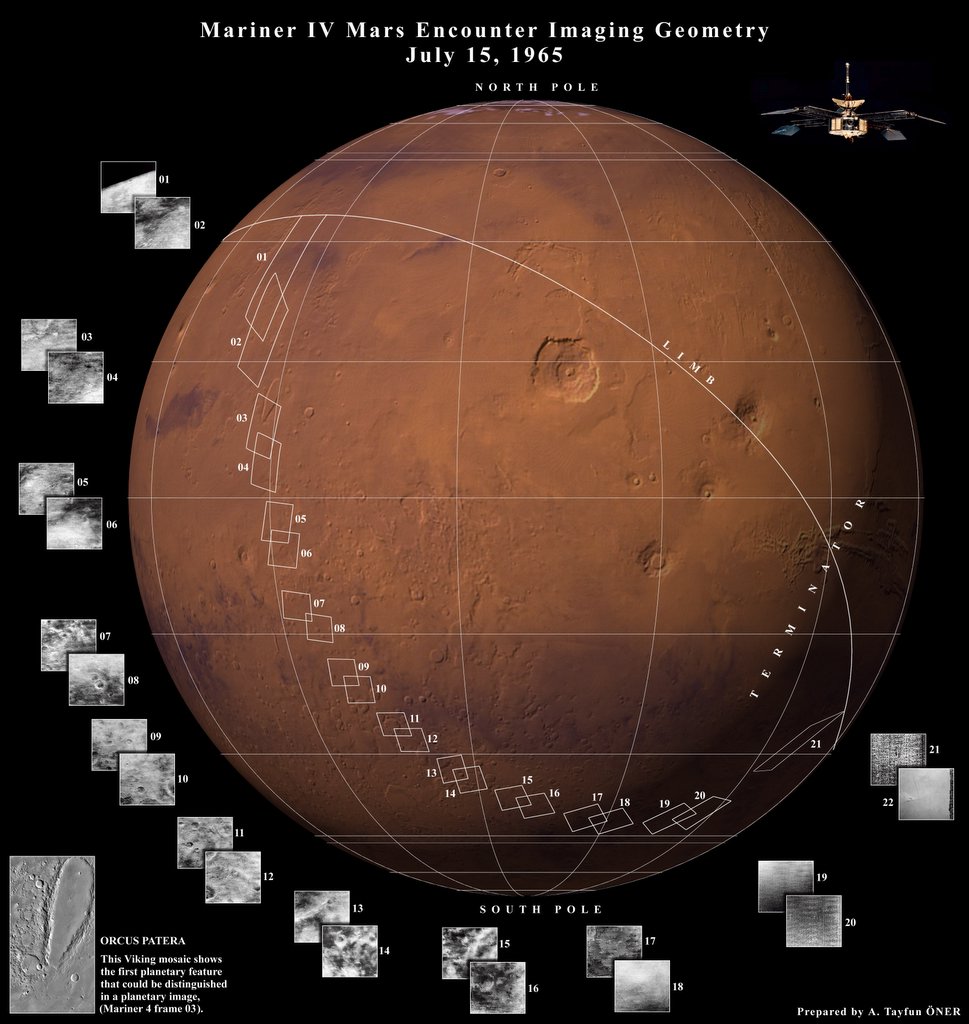

Five failures, one after the other, that must have been heartbreaking. Then the Americans took a crack at it with Mariner 3, but it didn’t get into the right trajectory to reach Mars.

Finally, in 1964 the first attempt to reach Mars was successful with Mariner 4. We got a handful of blurry images from a brief flyby.

For the next decade, both the Soviets and Americans threw all kinds of hapless robots on a collision course with Mars, both orbiters and landers. There were a few successes, like Mariner 6 and 7, and Mariner 9 which went into orbit for the first time in 1971. But mostly, it was failure. The Soviets suffered 10 missions that either partially or fully failed. There were a couple of orbiters that made it safely to the Red Planet, but their lander payloads were destroyed. That sounds familiar.

Now, don’t feel too bad about the Soviets. While they were struggling to get to Mars, they were having wild success with their Venera program, orbiting and eventually landing on the surface of Venus. They even sent a few pictures back.

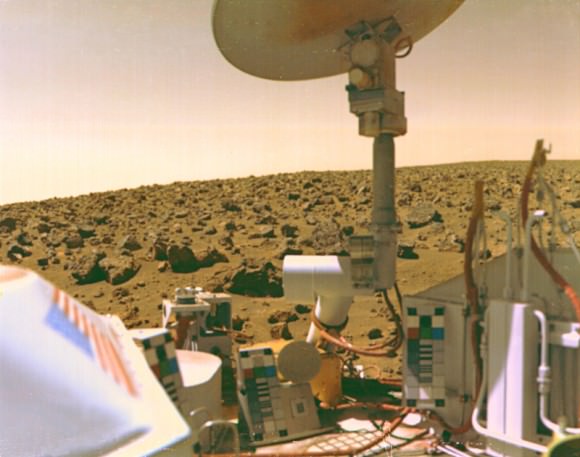

Finally, the Americans saw their greatest success in Mars exploration: the Viking Missions. Viking 1 and Viking 2 both consisted of an orbiter/lander combination, and both spacecraft were a complete success.

Was the Mars Curse over? Not even a little bit. During the 1990s, the Russians lost a mission, the Japanese lost a mission, and the Americans lost 3, including the Mars Observer, Mars Climate Orbiter and the Mars Polar Lander.

There were some great successes, though, like the Mars Global Surveyor and the Mars Pathfinder. You know, the one with the Sojourner Rover that’s going to save Mark Watney?

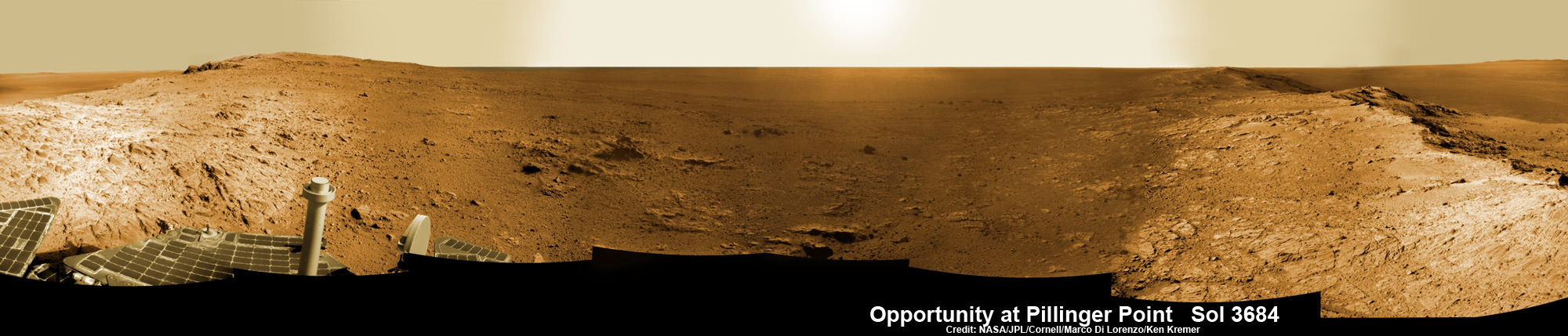

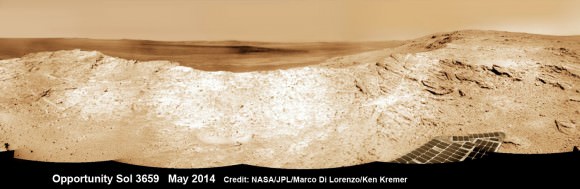

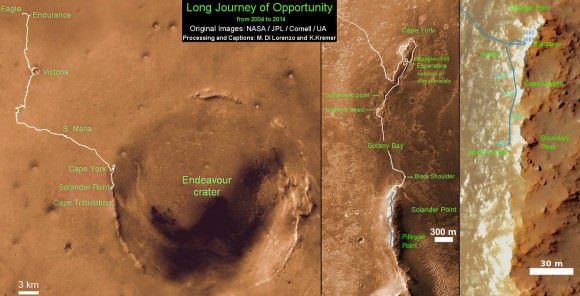

The 2000s have been good. Every single American mission has been successful, including Spirit and Opportunity, Curiosity, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and others.

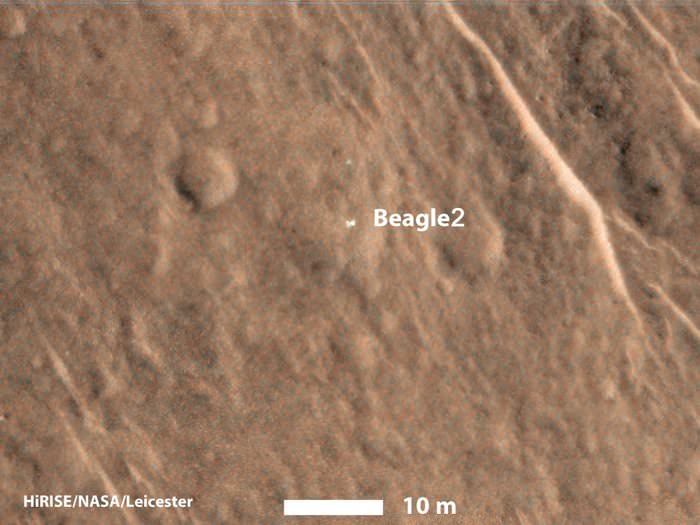

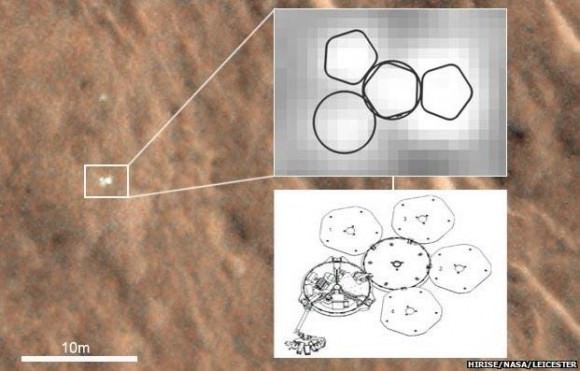

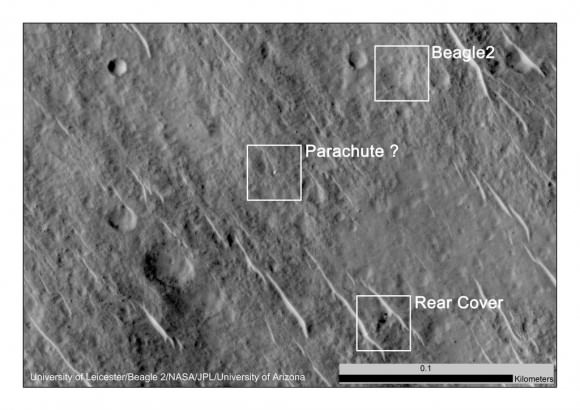

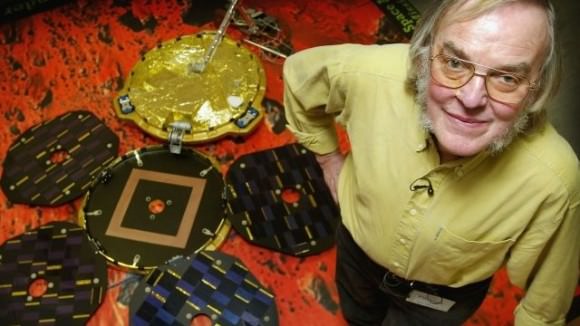

But the Mars Curse just won’t leave the Europeans alone. It consumed the Russian Fobos-Grunt mission, the Beagle 2 Lander, and now, poor Schiaparelli. Of the 20 missions to Mars sent by European countries, only 4 have had partial successes, with their orbiters surviving, while their landers or rovers were smashed.

Is there something to this curse? Is there a Galactic Ghoul at Mars waiting to consume any spacecraft that dare to venture in its direction?

Flying to Mars is tricky business, and it starts with just getting off Earth. The escape velocity you need to get into low-Earth orbit is about 7.8 km/s. But if you want to go straight to Mars, you need to be going 11.3 km/s. Which means you might want a bigger rocket, more fuel, going faster, with more stages. It’s a more complicated and dangerous affair.

Your spacecraft needs to spend many months in interplanetary space, exposed to the solar winds and cosmic radiation.

Arriving at Mars is harder too. The atmosphere is very thin for aerobraking. If you’re looking to go into orbit, you need to get the trajectory exactly right or crash onto the planet or skip off and out into deep space.

And if you’re actually trying to land on Mars, it’s incredibly difficult. The atmosphere isn’t thin enough to use heatshields and parachutes like you can on Earth. And it’s too thick to let you just land with retro-rockets like they did on the Moon.

Landers need a combination of retro-rockets, parachutes, aerobraking and even airbags to make the landing. If any one of these systems fails, the spacecraft is destroyed, just like Schiaparelli.

If I was in charge of planning a human mission to Mars, I would never forget that half of all spacecraft ever sent to the Red Planet failed. The Galactic Ghoul has never tasted human flesh before. Let’s put off that first meal for as long as we can.