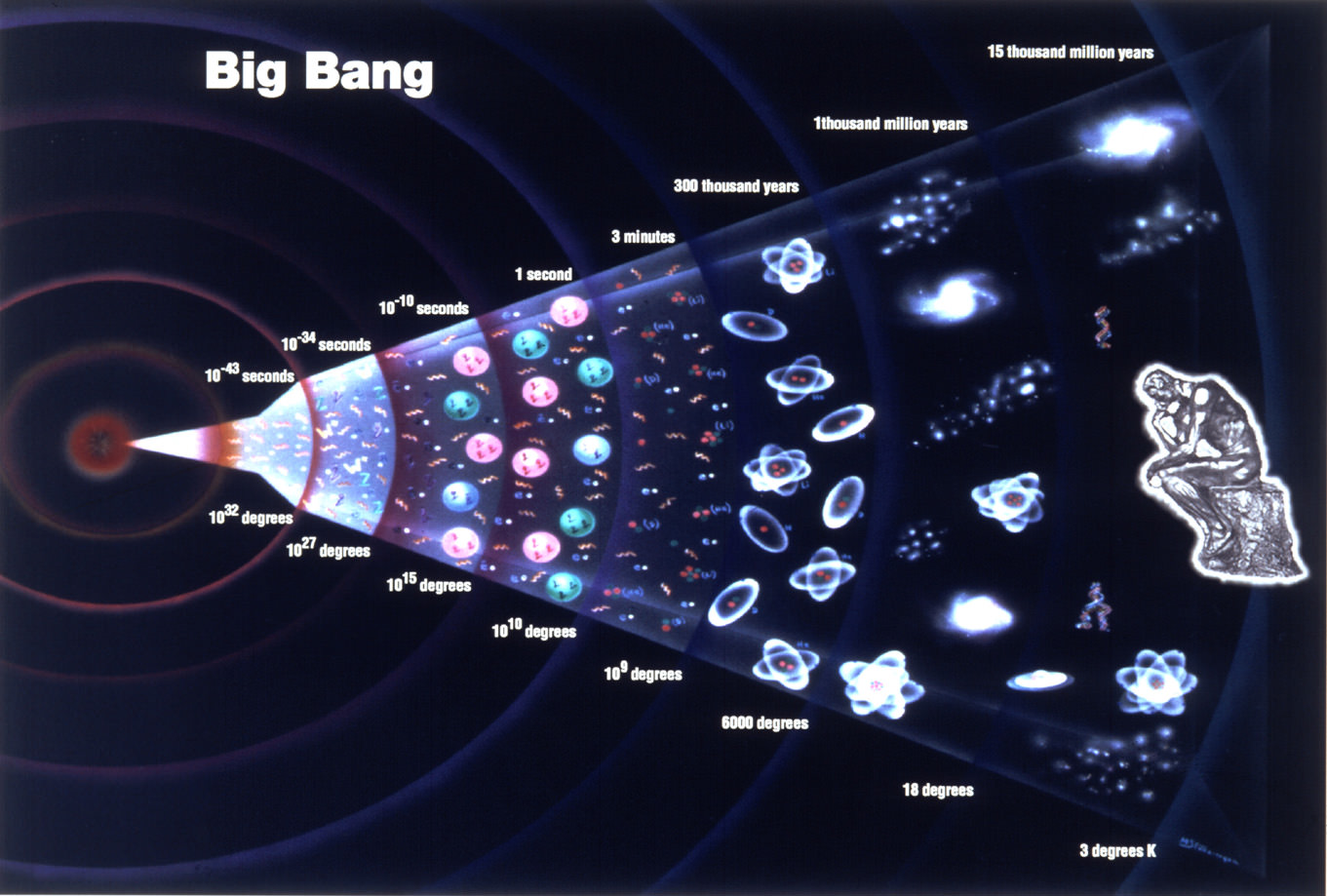

We owe our entire existence to the Sun. Well, it and the other stars that came before. As they died, they donated the heavier elements we need for life. But how did they form?

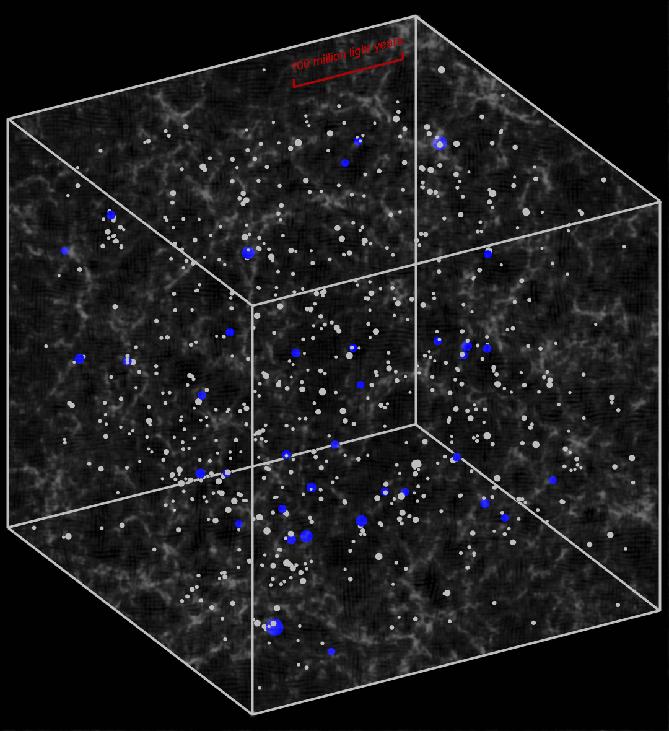

Stars begin as vast clouds of cold molecular hydrogen and helium left over from the Big Bang. These vast clouds can be hundreds of light years across and contain the raw material for thousands or even millions of times the mass of our Sun. In addition to the hydrogen, these clouds are seeded with heavier elements from the stars that lived and died long ago. They’re held in balance between their inward force of gravity and the outward pressure of the molecules. Eventually some kick overcomes this balance and causes the cloud to begin collapsing.

That kick could come from a nearby supernova explosion, collision with another gas cloud, or the pressure wave of a galaxy’s spiral arms passing through the region. As this cloud collapses, it breaks into smaller and smaller clumps, until there are knots with roughly the mass of a star. As these regions heat up, they prevent further material from falling inward.

At the center of these clumps, the material begins to increase in heat and density. When the outward pressure balances against the force of gravity pulling it in, a protostar is formed. What happens next depends on the amount of material.

Some objects don’t accumulate enough mass for stellar ignition and become brown dwarfs – substellar objects not unlike a really big Jupiter, which slowly cool down over billions of years.

If a star has enough material, it can generate enough pressure and temperature at its core to begin deuterium fusion – a heavier isotope of hydrogen. This slows the collapse and prepares the star to enter the true main sequence phase. This is the stage that our own Sun is in, and begins when hydrogen fusion begins.

If a protostar contains the mass of our Sun, or less, it undergoes a proton-proton chain reaction to convert hydrogen to helium. But if the star has about 1.3 times the mass of the Sun, it undergoes a carbon-nitrogen-oxygen cycle to convert hydrogen to helium. How long this newly formed star will last depends on its mass and how quickly it consumes hydrogen. Small red dwarf stars can last hundreds of billions of years, while large supergiants can consume their hydrogen within a few million years and detonate as supernovae. But how do stars explode and seed their elements around the Universe? That’s another episode.

We have written many articles about star formation on Universe Today. Here’s an article about star formation in the Large Magellanic Cloud, and here’s another about star formation in NGC 3576.

Want more information on stars? Here’s Hubblesite’s News Releases about Stars, and more information from NASA’s imagine the Universe.

We have recorded several episodes of Astronomy Cast about stars. Here are two that you might find helpful: Episode 12: Where Do Baby Stars Come From, and Episode 13: Where Do Stars Go When they Die?

Source: NASA