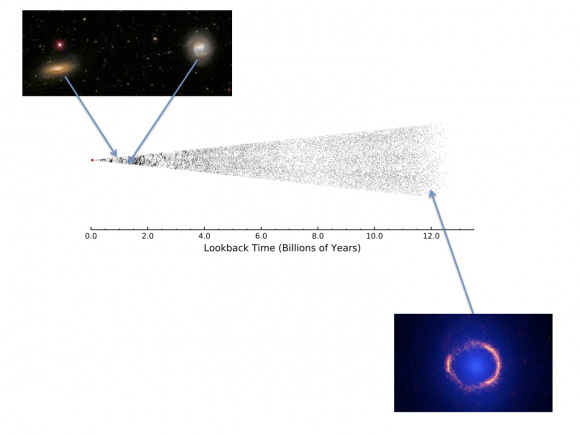

The speed of light gives us an amazing tool for studying the Universe. Because light only travels a mere 300,000 kilometers per second, when we see distant objects, we’re looking back in time.

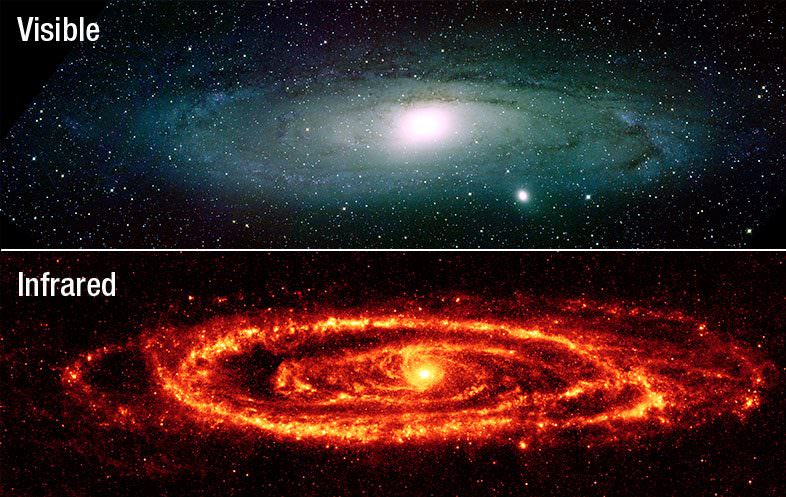

You’re not seeing the Sun as it is today, you’re seeing an 8 minute old Sun. You’re seeing 642 year-old Betelgeuse. 2.5 million year-old Andromeda. In fact, you can keep doing this, looking further out, and deeper into time. Since the Universe is expanding today, it was closer in the past.

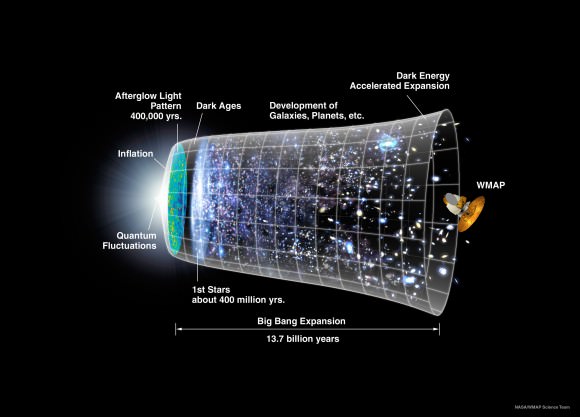

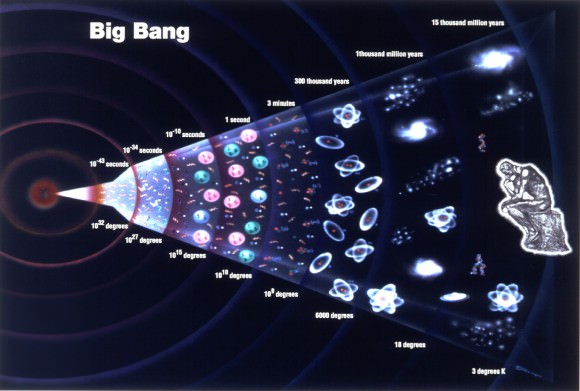

Run the Universe clock backwards, right to the beginning, and you get to a place that was hotter and denser than it is today. So dense that the entire Universe shortly after the Big Bang was just a soup of protons, neutrons and electrons, with nothing holding them together.

In fact, once it expanded and cooled down a bit, the entire Universe was merely as hot and as dense as the core of a star like our Sun. It was cool enough for ionized atoms of hydrogen to form.

Because the Universe has the conditions of the core of a star, it had the temperature and pressure to actually fuse hydrogen into helium and other heavier elements. Based on the ratio of those elements we see in the Universe today: 74% hydrogen, 25% helium and 1% miscellaneous, we know how long the Universe was in this “whole Universe is a star” condition.

It lasted about 17 minutes. From 3 minutes after the Big Bang until about 20 minutes after the Big Bang. In those few, short moments, clowns gathered all the helium they would ever need to haunt us with a lifetime of balloon animals.

The fusion process generates photons of gamma radiation. In the core of our Sun, these photons bounce from atom to atom, eventually making their way out of the core, through the Sun’s radiative zone, and eventually out into space. This process can take tens of thousands of years. But in the early Universe, there was nowhere for these primordial photons of gamma radiation to go. Everywhere was more hot, dense Universe.

The Universe was continuing to expand, and finally, just a few hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, the Universe was finally cool enough for these atoms of hydrogen and helium to attract free electrons, turning them into neutral atoms.

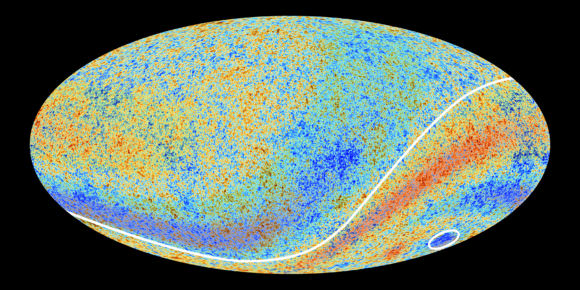

This was the moment of first light in the Universe, between 240,000 and 300,000 years after the Big Bang, known as the Era of Recombination. The first time that photons could rest for a second, attached as electrons to atoms. It was at this point that the Universe went from being totally opaque, to transparent.

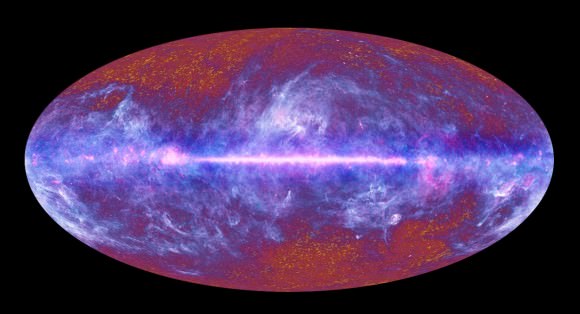

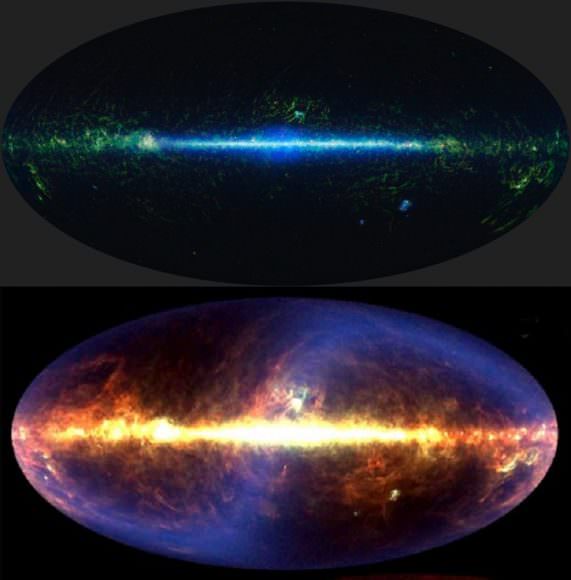

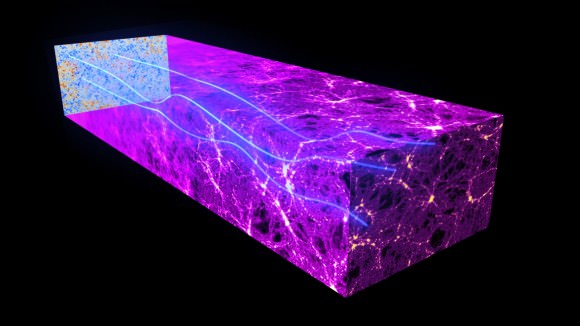

And this is the earliest possible light that astronomers can see. Go ahead, say it with me: the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. Because the Universe has been expanding over the 13.8 billion years from then until now, the those earliest photons were stretched out, or red-shifted, from ultraviolet and visible light into the microwave end of the spectrum.

If you could see the Universe with microwave eyes, you’d see that first blast of radiation in all directions. The Universe celebrating its existence.

After that first blast of light, everything was dark, there were no stars or galaxies, just enormous amounts of these primordial elements. At the beginning of these dark ages, the temperature of the entire Universe was about 4000 kelvin. Compare that with the 2.7 kelvin we see today. By the end of the dark ages, 150 million years later, the temperature was a more reasonable 60 kelvin.

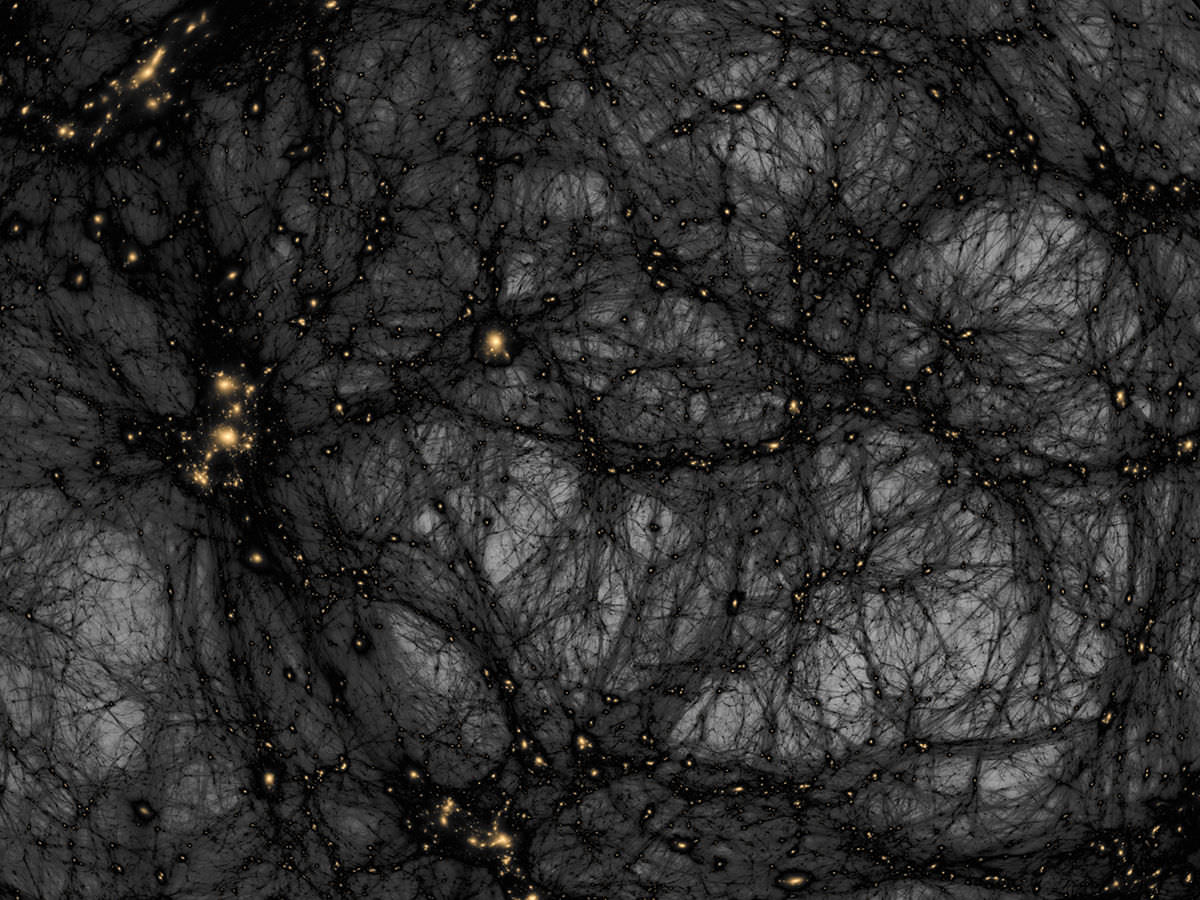

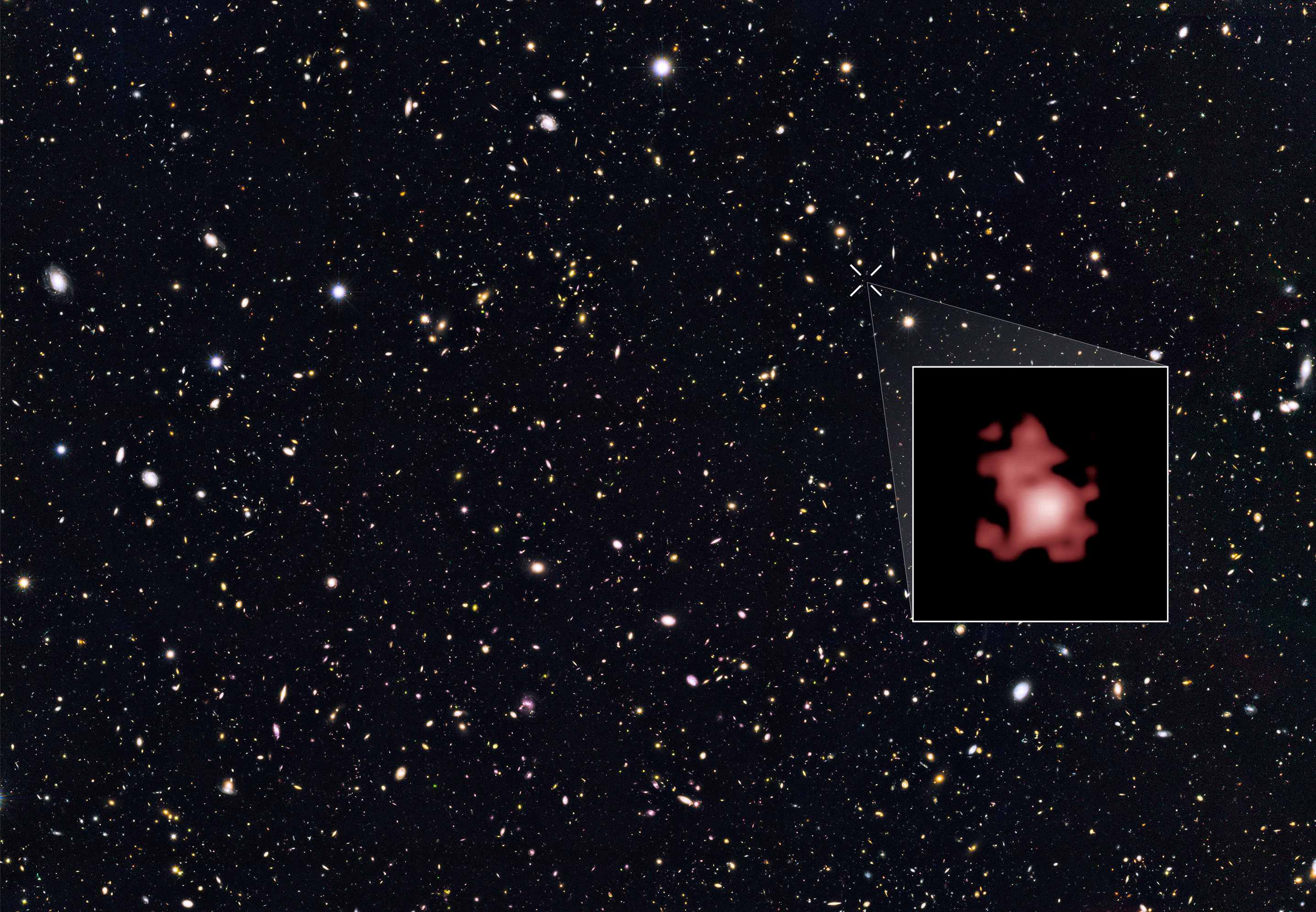

For the next 850 million years or so, these elements came together into monster stars of pure hydrogen and helium. Without heavier elements, they were free to form stars with dozens or even hundreds of times the mass of our own Sun. These are the Population III stars, or the first stars, and we don’t have telescopes powerful enough to see them yet. Astronomers indirectly estimate that those first stars formed about 560 million years after the Big Bang.

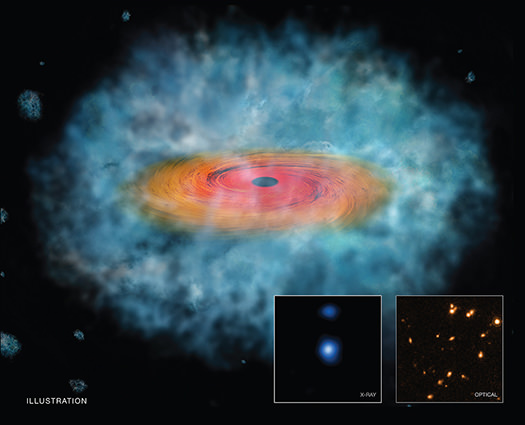

Then, those first stars exploded as supernovae, more massive stars formed and they detonated as well. It’s seriously difficult to imagine what that time must have looked like, with stars going off like fireworks. But we know it was so common and so violent that it lit up the whole Universe in an era called reionization. Most of the Universe was hot plasma.

The early Universe was hot and awful, and there weren’t a lot of the heavier elements that life as we know it depends on. Just think about it. You can’t get oxygen without fusion in a star, even multiple generations. Our own Solar System is the result of several generations of supernovae that exploded, seeding our region with heavier and heavier elements.

As I mentioned earlier in the article, the Universe cooled from 4000 kelvin down to 60 kelvin. About 10 million years after the Big Bang, the temperature of the Universe was 100 C, the boiling point of water. And then 7 million years later, it was down to 0 C, the freezing point of water.

This has led astronomers to theorize that for about 7 million years, liquid water was present across the Universe… everywhere. And wherever we find liquid water on Earth, we find life.

So it’s possible, possible that primitive life could have formed with the Universe was just 10 million years old. The physicist Avi Loeb calls this the habitable Epoch of the Universe. No evidence, but it’s a pretty cool idea to think about.

I always find it absolutely mind bending to think that all around us in every direction is the first light from the Universe. It’s taken 13.8 billion years to reach us, and although we need microwave eyes to actually see it, it’s there, everywhere.