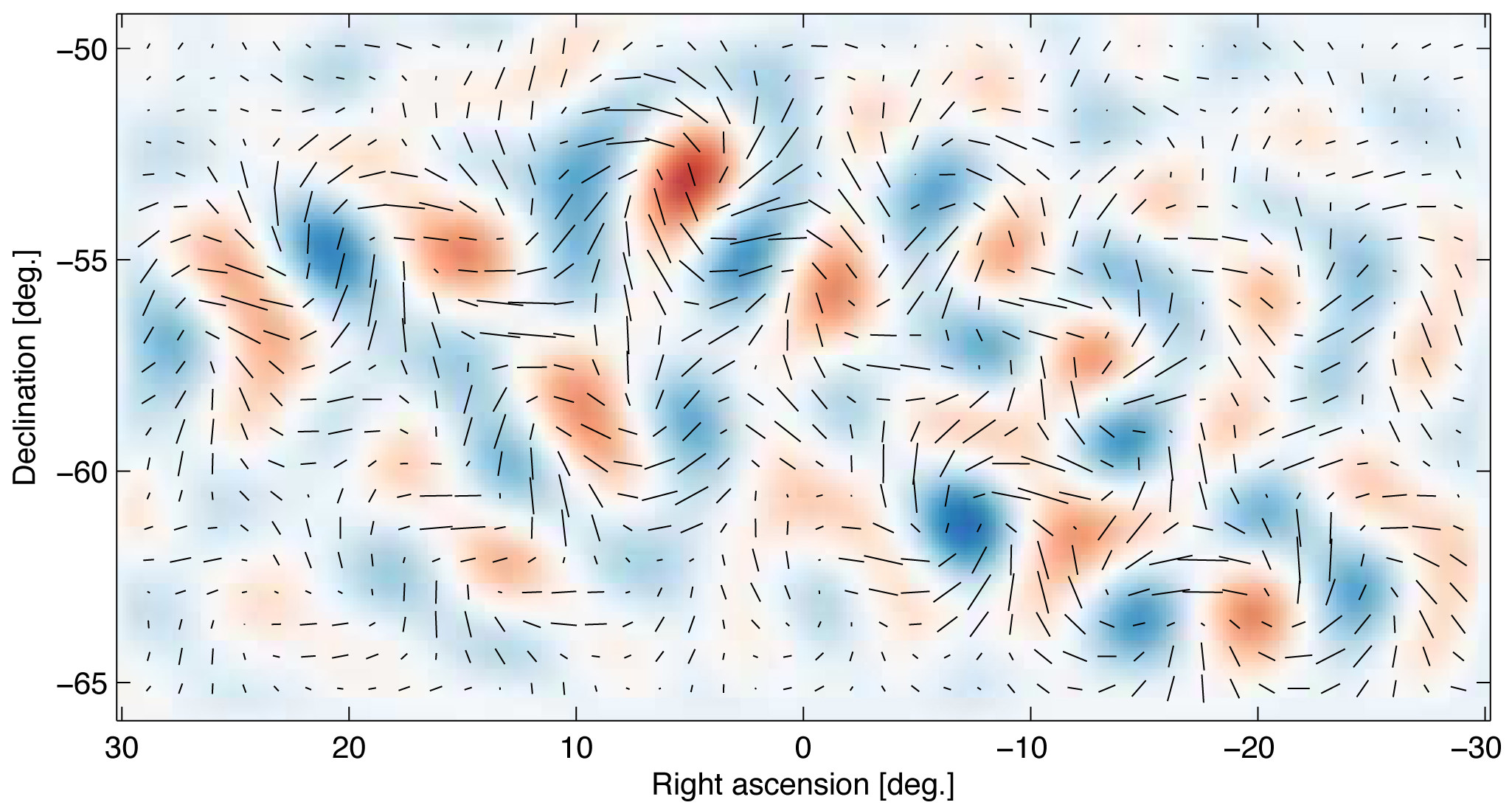

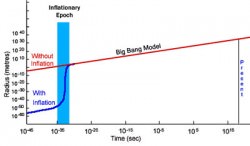

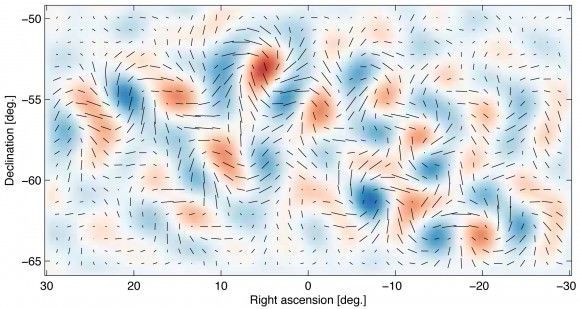

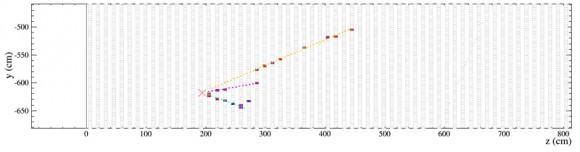

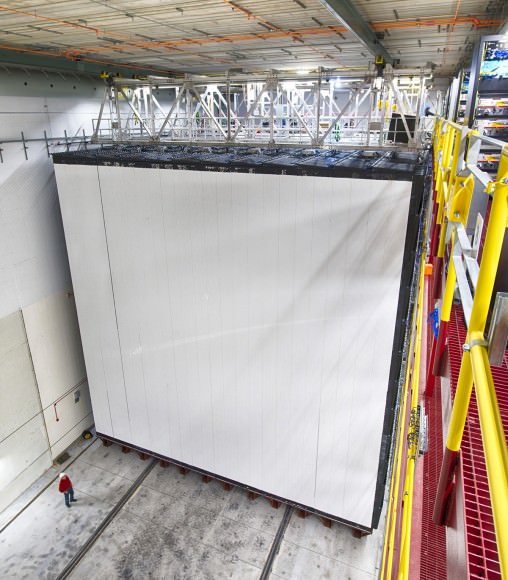

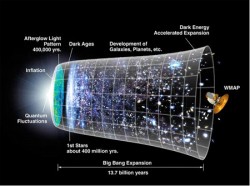

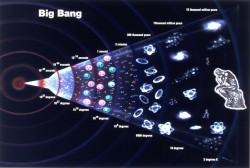

It was just a week ago that the news blew through the scientific world like a storm: researchers from the BICEP2 project at the South Pole Telescope had detected unambiguous evidence of primordial gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background, the residual rippling of space and time created by the sudden inflation of the Universe less than a billionth of a billionth of a second after the Big Bang. With whispers of Nobel nominations quickly rising in the science news wings, the team’s findings were hailed as the best direct evidence yet of cosmic inflation, possibly even supporting the existence of a multitude of other universes besides our own.

That is, if they really do indicate what they appear to. Some theorists are advising that we “put the champagne back in the fridge”… at least for now.

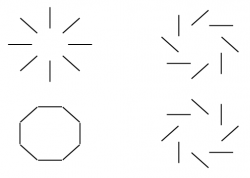

Theoretical physicists and cosmologists James Dent, Lawrence Krauss, and Harsh Mathur have submitted a brief paper (arXiv:1403.5166 [astro-ph.CO]) stating that, while groundbreaking, the BICEP2 Collaboration findings have yet to rule out all possible non-inflation sources of the observed B-mode polarization patterns and the “surprisingly large value of r, the ratio of power in tensor modes to scalar density perturbations.”

“However, while there is little doubt that inflation at the Grand Unified Scale is the best motivated source of such primordial waves, it is important to demonstrate that other possible sources cannot account for the current BICEP2 data before definitely claiming Inflation has been proved. “

– Dent, Krauss, and Mathur (arXiv:1403.5166 [astro-ph.CO])

Inflation may very well be the cause — and Dent and company state right off the bat that “there is little doubt that inflation at the Grand Unified Scale is the best motivated source of such primordial waves” — but there’s also a possibility, however remote, that some other, later cosmic event is responsible for at least some if not all of the BICEP2 measurements. (Hence the name of the paper: “Killing the Straw Man: Does BICEP Prove Inflation?”)

Not intending to entirely rain out the celebration, Dent, Krauss, and Mathur do laud the BICEP2 findings as invaluable to physics, stating that they “will be very important for constraining physics beyond the standard model, whether or not inflation is responsible for the entire BICEP2 signal, even though existing data from cosmology is strongly suggestive that it does.”

Read more: We’ve Discovered Inflation! Now What?

Now I’m no physicist, cosmologist, or astronomer. Actually I barely passed high school algebra (and I have the transcripts to prove it) so if you want to get into the finer details of this particular argument I invite you to read the team’s paper for yourself here and check out a complementary article on The Physics arXiv Blog.

And so, for better or worse (just kidding — it’s definitely better) this is how science works and how science is supposed to work. A claim is presented, and, regardless of how attractive its implications may be, it must stand up to any other possibilities before deemed the decisive winner. It’s not a popularity contest, it’s not a beauty contest, and it’s not up for vote. What it is up for is scrutiny, and this is just an example of scientists behaving as they should.

Still, I’d keep that champagne nicely chilled.

Source: The Physics arXiv Blog

_________

Want to read more about the BICEP2 findings from actual physicists? Read more in an article by Peter Coles, see what Matthew Francis has to say in his article on arstechnica here, and watch a video by Sean Carroll on PBS News Hour.