If you’re a semi-serious amateur astronomer, chances are you’ve heard of a variable pair of stars called SS Cygni. When you watch the system for long enough, you’re rewarded with a brightness outburst that then fades away and then returns, regularly, over and over again.

Turns out this bright pair is even closer to us than we imagined — 370 light-years away, to be precise.

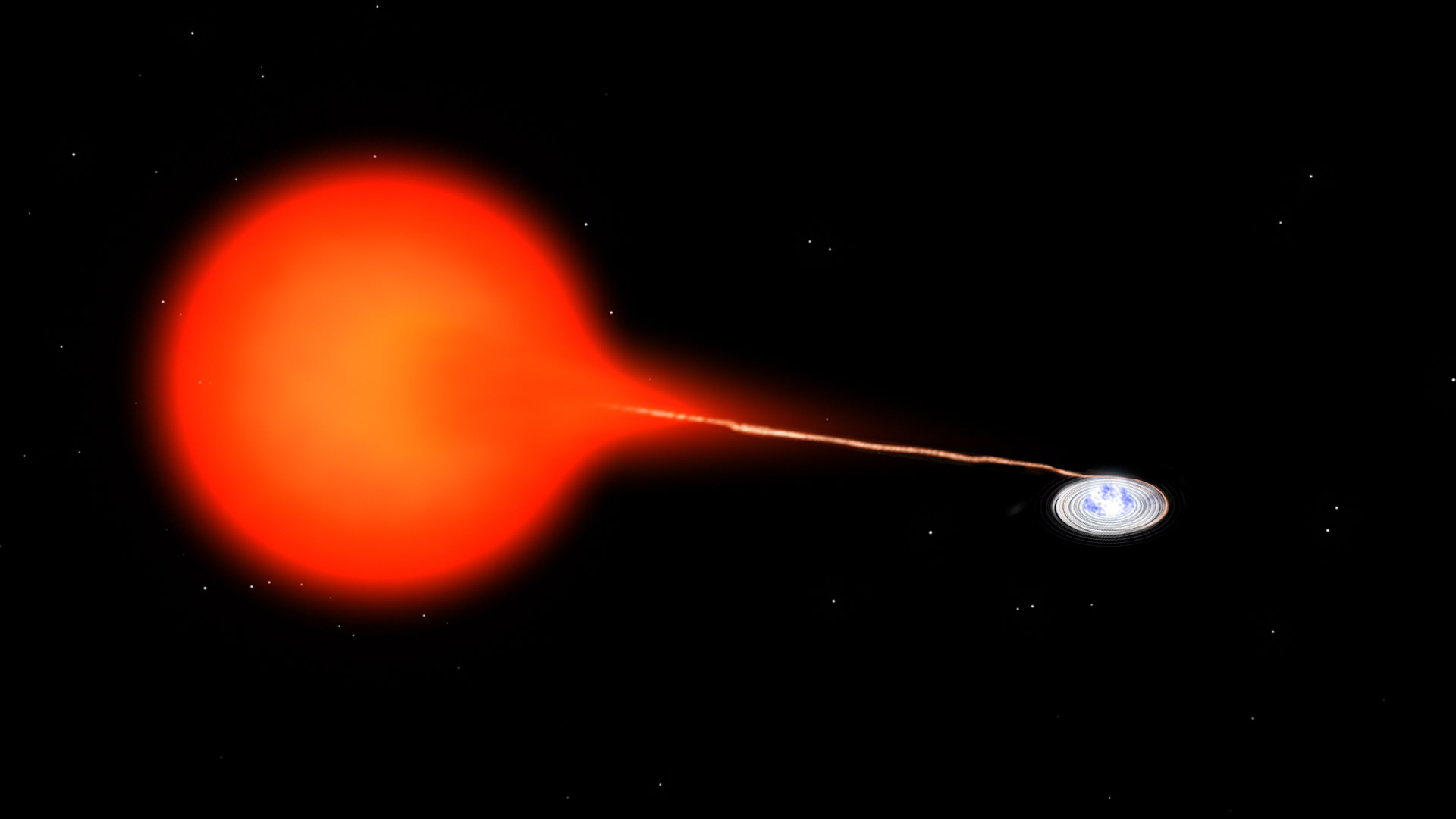

Before we get into how this was discovered, a bit of background on what SS Cygni is. As the name of the system implies, it’s in the constellation of Cygnus (the Swan). The pair consists of a cooling white dwarf star that is locked in a 6.6-hour orbit with a red dwarf.

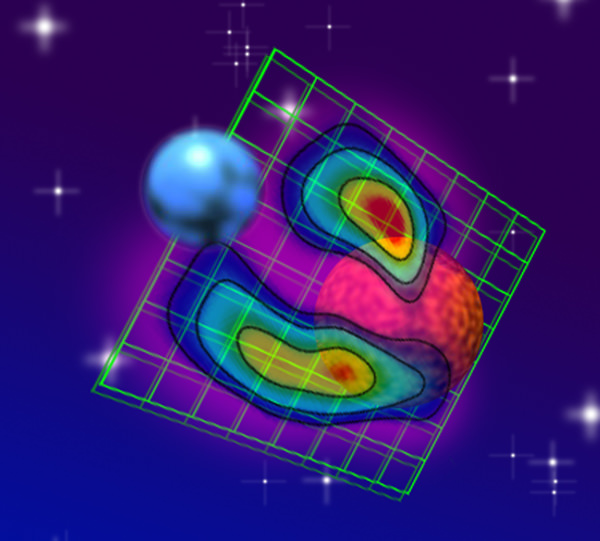

The white dwarf’s gravity, which is much stronger than that of the red dwarf, is bleeding material from its neighbor. This interaction causes outbursts — on average, about once every 50 days.

Previously, the Hubble Space Telescope put the distance to these stars much further away, at 520 light-years. But that caused some head-scratching among astronomers.

“That was a problem. At that distance, SS Cygni would have been the brightest dwarf nova in the sky, and should have had enough mass moving through its disk to remain stable without any outbursts,” stated James Miller-Jones, of the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, Australia.

Astronomers call SS Cygni a dwarf nova. When comparing it to similar systems, astronomers said the outbursts happen as matter changes its flow speed through the disc of material surrounding the white dwarf.

“At high rates of mass transfer from the red dwarf, the rotating disk remains stable, but when the rate is lower, the disk can become unstable and undergo an outburst,” stated the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. So what was happening?

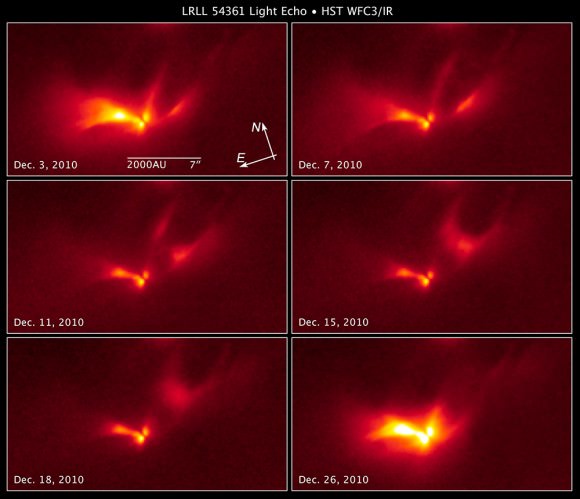

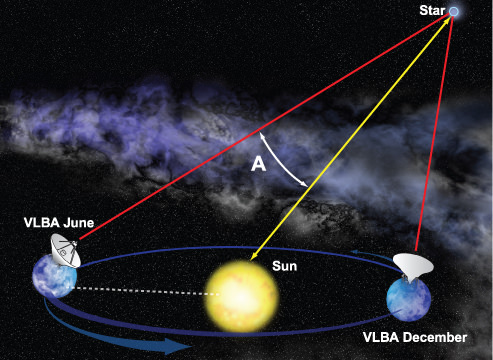

To again look at the distance of the star, astronomers used two sets of radio telescopes, the Very Large Baseline Array and the European VLBI Network. Each set has a bunch of telescopes working together as an interferometer, allowing for precise measurements of star distances.

Scientists then took measurements at opposite ends of the Earth’s orbit, using the planet itself as a tool. By measuring the star’s distance at opposite sides of the orbit, we can calculate its parallax or apparent movement in the sky from the perspective of Earth. It’s an old astronomical tool used to pin down distances, and still works.

“This is one of the best-studied systems of its type, but according to our understanding of how these things work, it should not have been having outbursts. The new distance measurement brings it into line with the standard explanation,” stated Miller-Jones.

And where did Hubble go wrong? Here’s the theory:

“The radio observations were made against a background of objects far beyond our own Milky Way Galaxy, while the Hubble observations used stars within our galaxy as reference points,” NRAO stated. “The more-distant objects provide a better, more stable, reference.”

The results were published in Science on May 24.