A recent paper by Stephen Hawking has created quite a stir, even leading Nature News to declare there are no black holes. As I wrote in an earlier post, that isn’t quite what Hawking claimed. But it is now clear that Hawking’s claim about black holes is wrong because the paradox he tries to address isn’t a paradox after all.

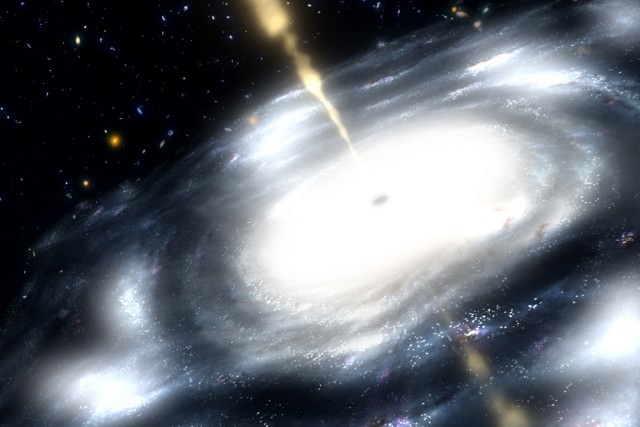

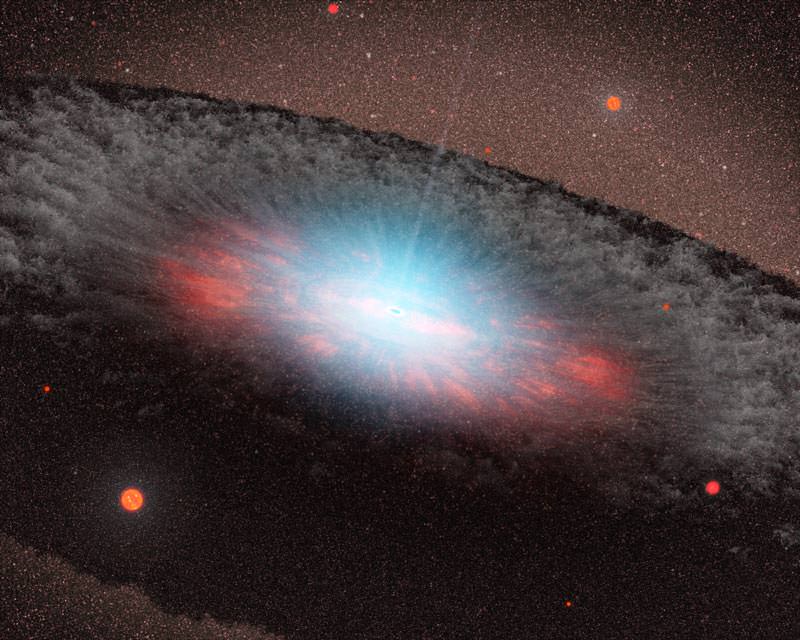

It all comes down to what is known as the firewall paradox for black holes. The central feature of a black hole is its event horizon. The event horizon of a black hole is basically the point of no return when approaching a black hole. In Einstein’s theory of general relativity, the event horizon is where space and time are so warped by gravity that you can never escape. Cross the event horizon and you are forever trapped.

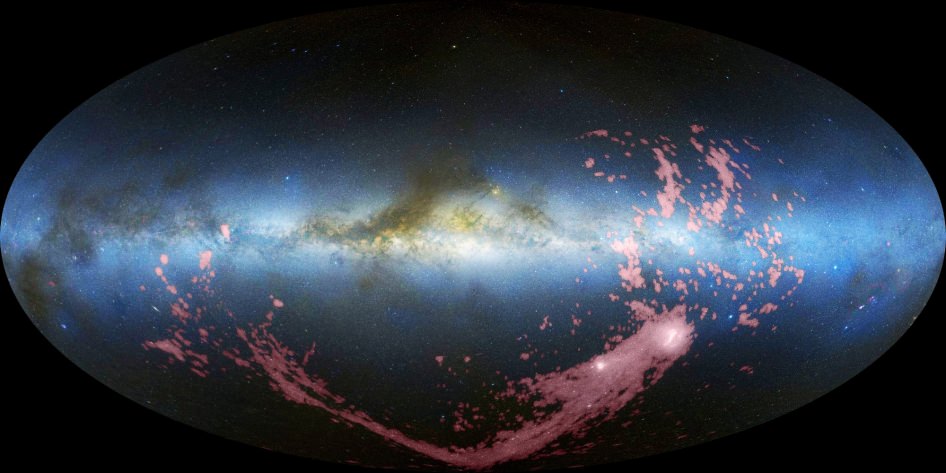

This one-way nature of an event horizon has long been a challenge to understanding gravitational physics. For example, a black hole event horizon would seem to violate the laws of thermodynamics. One of the principles of thermodynamics is that nothing should have a temperature of absolute zero. Even very cold things radiate a little heat, but if a black hole traps light then it doesn’t give off any heat. So a black hole would have a temperature of zero, which shouldn’t be possible.

Then in 1974 Stephen Hawking demonstrated that black holes do radiate light due to quantum mechanics. In quantum theory there are limits to what can be known about an object. For example, you cannot know an object’s exact energy. Because of this uncertainty, the energy of a system can fluctuate spontaneously, so long as its average remains constant. What Hawking demonstrated is that near the event horizon of a black hole pairs of particles can appear, where one particle becomes trapped within the event horizon (reducing the black holes mass slightly) while the other can escape as radiation (carrying away a bit of the black hole’s energy).

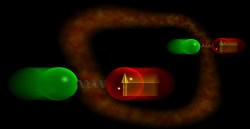

While Hawking radiation solved one problem with black holes, it created another problem known as the firewall paradox. When quantum particles appear in pairs, they are entangled, meaning that they are connected in a quantum way. If one particle is captured by the black hole, and the other escapes, then the entangled nature of the pair is broken. In quantum mechanics, we would say that the particle pair appears in a pure state, and the event horizon would seem to break that state.

Last year it was shown that if Hawking radiation is in a pure state, then either it cannot radiate in the way required by thermodynamics, or it would create a firewall of high energy particles near the surface of the event horizon. This is often called the firewall paradox because according to general relativity if you happen to be near the event horizon of a black hole you shouldn’t notice anything unusual. The fundamental idea of general relativity (the principle of equivalence) requires that if you are freely falling toward near the event horizon there shouldn’t be a raging firewall of high energy particles. In his paper, Hawking proposed a solution to this paradox by proposing that black holes don’t have event horizons. Instead they have apparent horizons that don’t require a firewall to obey thermodynamics. Hence the declaration of “no more black holes” in the popular press.

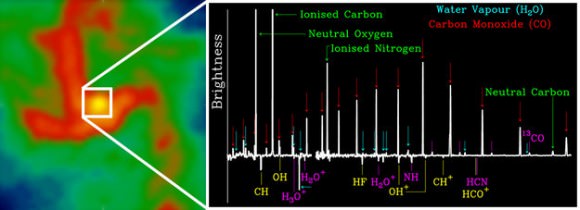

But the firewall paradox only arises if Hawking radiation is in a pure state, and a paper last month by Sabine Hossenfelder shows that Hawking radiation is not in a pure state. In her paper, Hossenfelder shows that instead of being due to a pair of entangled particles, Hawking radiation is due to two pairs of entangled particles. One entangled pair gets trapped by the black hole, while the other entangled pair escapes. The process is similar to Hawking’s original proposal, but the Hawking particles are not in a pure state.

So there’s no paradox. Black holes can radiate in a way that agrees with thermodynamics, and the region near the event horizon doesn’t have a firewall, just as general relativity requires. So Hawking’s proposal is a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist.

What I’ve presented here is a very rough overview of the situation. I’ve glossed over some of the more subtle aspects. For a more detailed (and remarkably clear) overview check out Ethan Seigel’s post on his blog Starts With a Bang! Also check out the post on Sabine Hossenfelder’s blog, Back Reaction, where she talks about the issue herself.