The sign of a truly great scientific theory is by the outcomes it predicts when you run experiments or perform observations. And one of the greatest theories ever proposed was the concept of Relativity, described by Albert Einstein in the beginning of the 20th century.

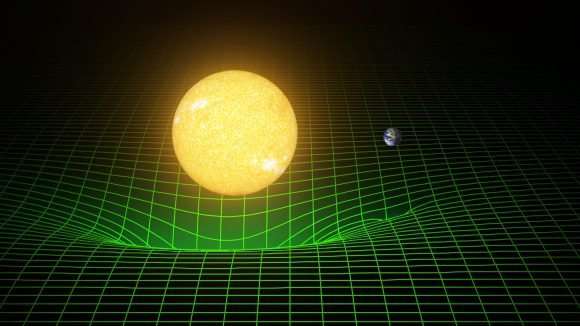

In addition to helping us understand that light is the ultimate speed limit of the Universe, Einstein described gravity itself as a warping of spacetime.

He did more than just provide a bunch of elaborate new explanations for the Universe, he proposed a series of tests that could be done to find out if his theories were correct.

One test, for example, completely explained why Mercury’s orbit didn’t match the predictions made by Newton. Other predictions could be tested with the scientific instruments of the day, like measuring time dilation with fast moving clocks.

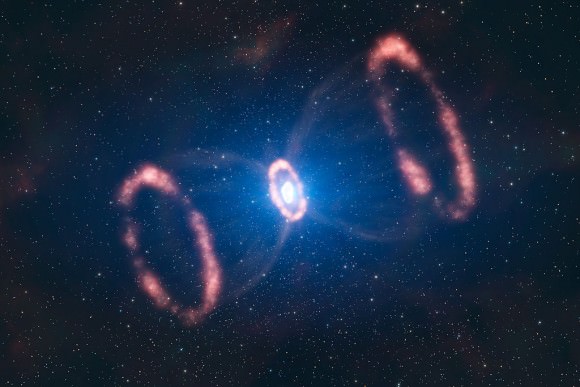

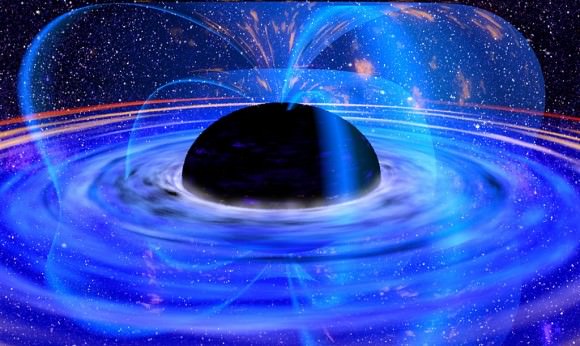

Since gravity is actually a distortion of spacetime, Einstein predicted that massive objects moving through spacetime should generate ripples, like waves moving through the ocean.

Just by walking around, you leave a wake of gravitational waves that compress and expand space around you. However, these waves are incredibly tiny. Only the most energetic events in the entire Universe can produce waves we can detect.

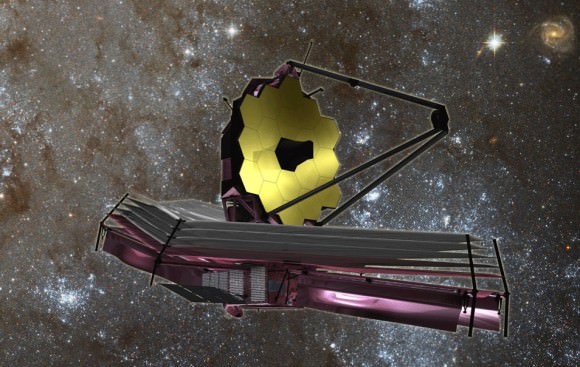

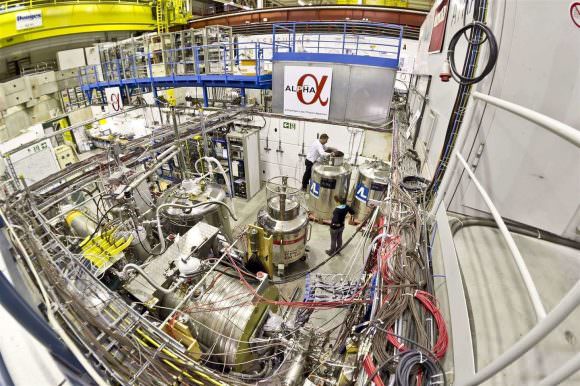

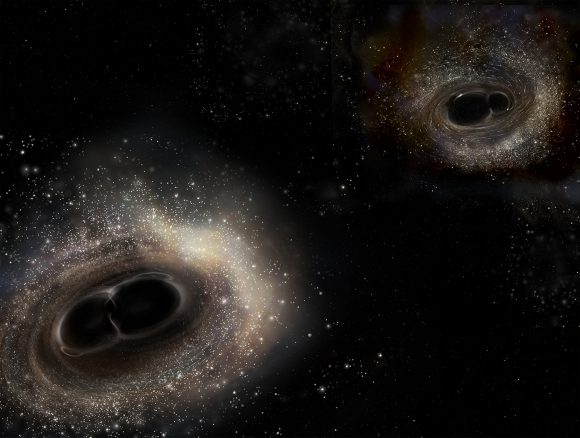

It took over 100 years to finally be proven true, the direct detection of gravitational waves. In February, 2016, physicists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory, or LIGO announced the collision of two massive black holes more than a billion light-years away.

Any size of black hole can collide. Plain old stellar mass black holes or supermassive black holes. Same process, just on a completely different scale.

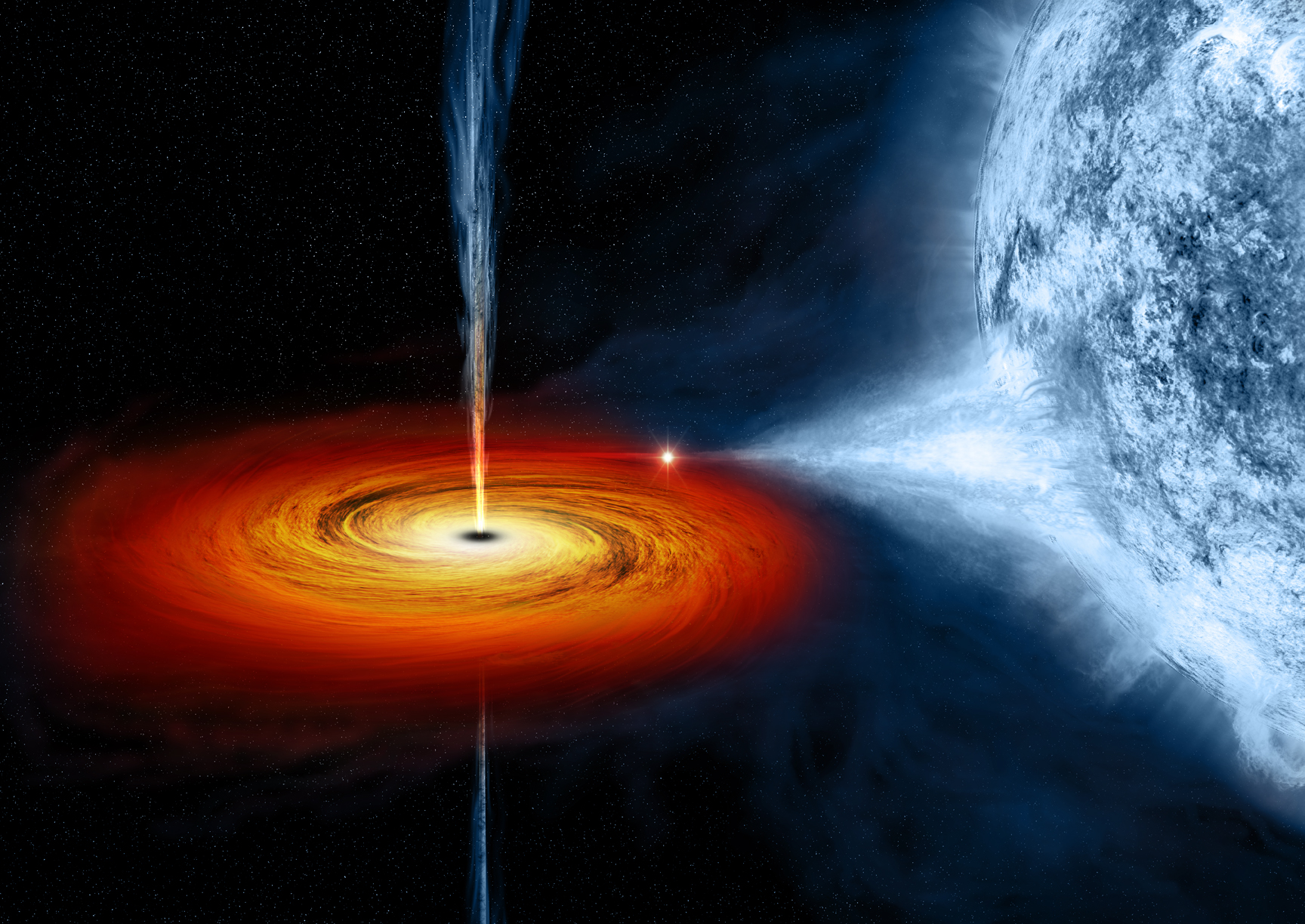

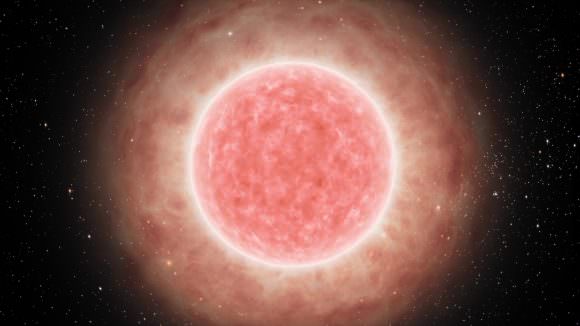

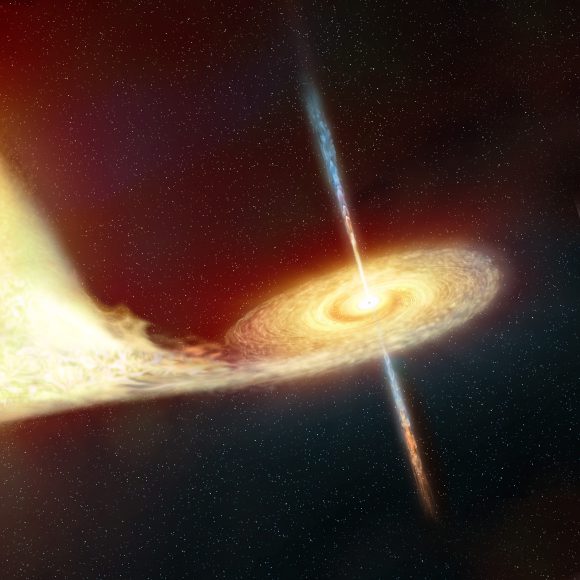

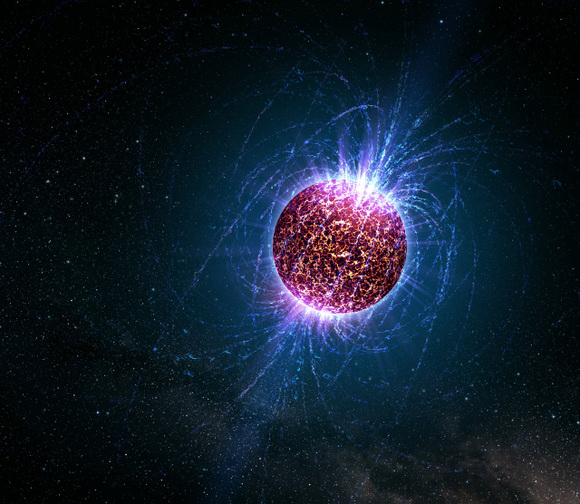

Let’s start with the stellar mass black holes. These, of course, form when a star with many times the mass of our Sun dies in a supernova. Just like regular stars, these massive stars can be in binary systems.

Imagine a stellar nebula where a pair of binary stars form. But unlike the Sun, each of these are monsters with many times the mass of the Sun, putting out thousands of times as much energy. The two stars will orbit one another for just a few million years, and then one will detonate as a supernova. Now you’ll have a massive star orbiting a black hole. And then the second star explodes, and now you have two black holes orbiting around each other.

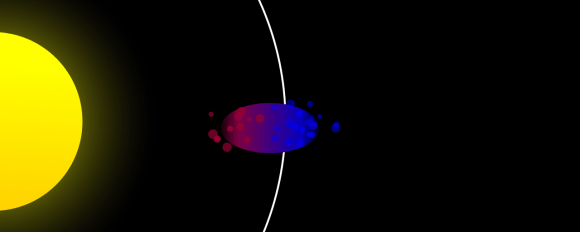

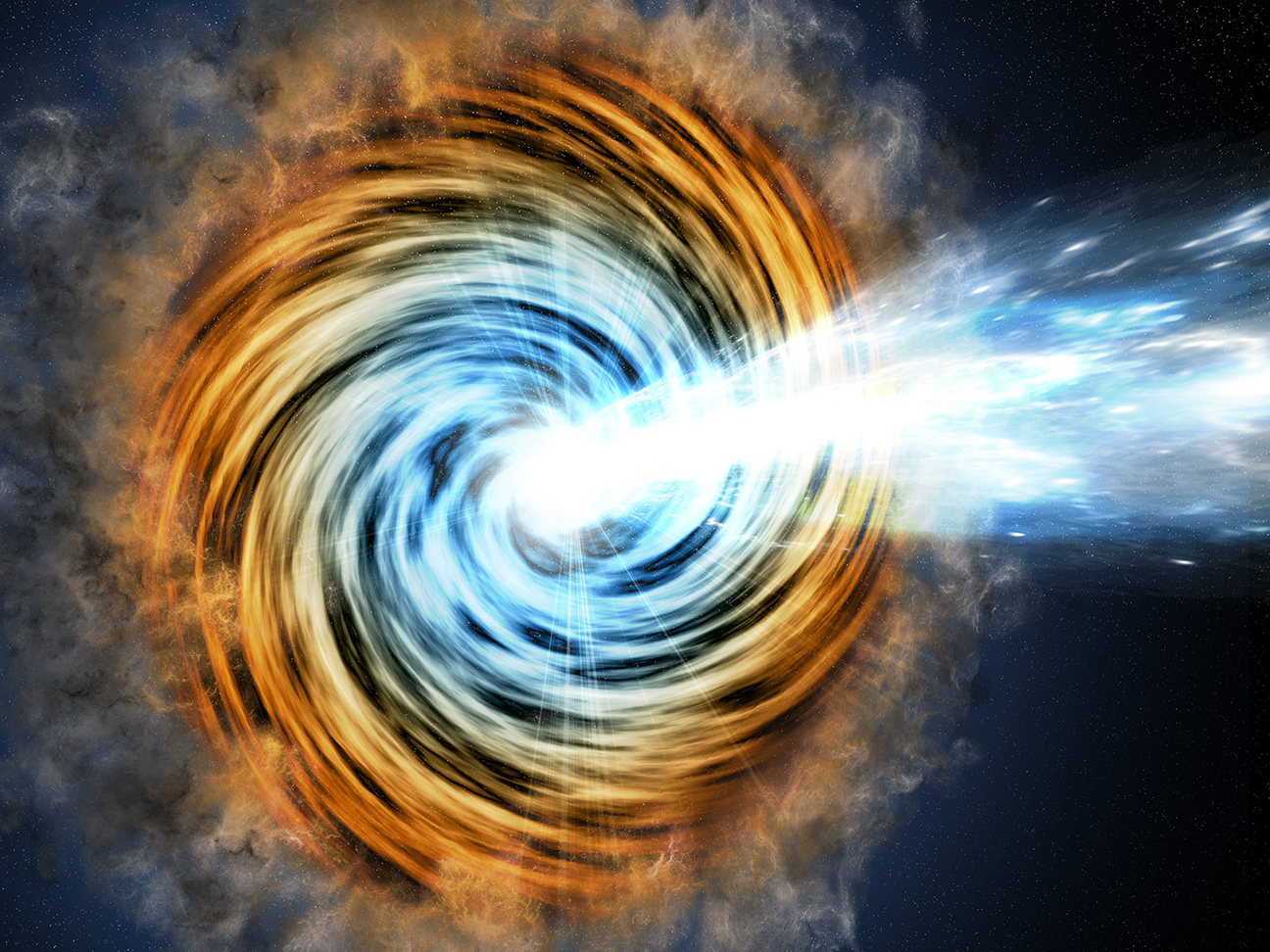

As the black holes zip around one another, they radiate gravitational waves which causes their orbit to decay. This is kind of mind-bending, actually. The black holes convert their momentum into gravitational waves.

As their angular momentum decreases, they spiral inward until they actually collide. What should be one of the most energetic explosions in the known Universe is completely dark and silent, because nothing can escape a black hole. No radiation, no light, no particles, no screams, nothing. And if you mash two black holes together, you just get a more massive black hole.

The gravitational waves ripple out from this momentous collision like waves through the ocean, and it’s detectable across more than a billion light-years.

This is exactly what happened earlier this year with the announcement from LIGO. This sensitive instrument detected the gravitational waves generated when two black holes with 30 solar masses collided about 1.3 billion light-years away.

This wasn’t a one-time event either, they detected another collision with two other stellar mass black holes.

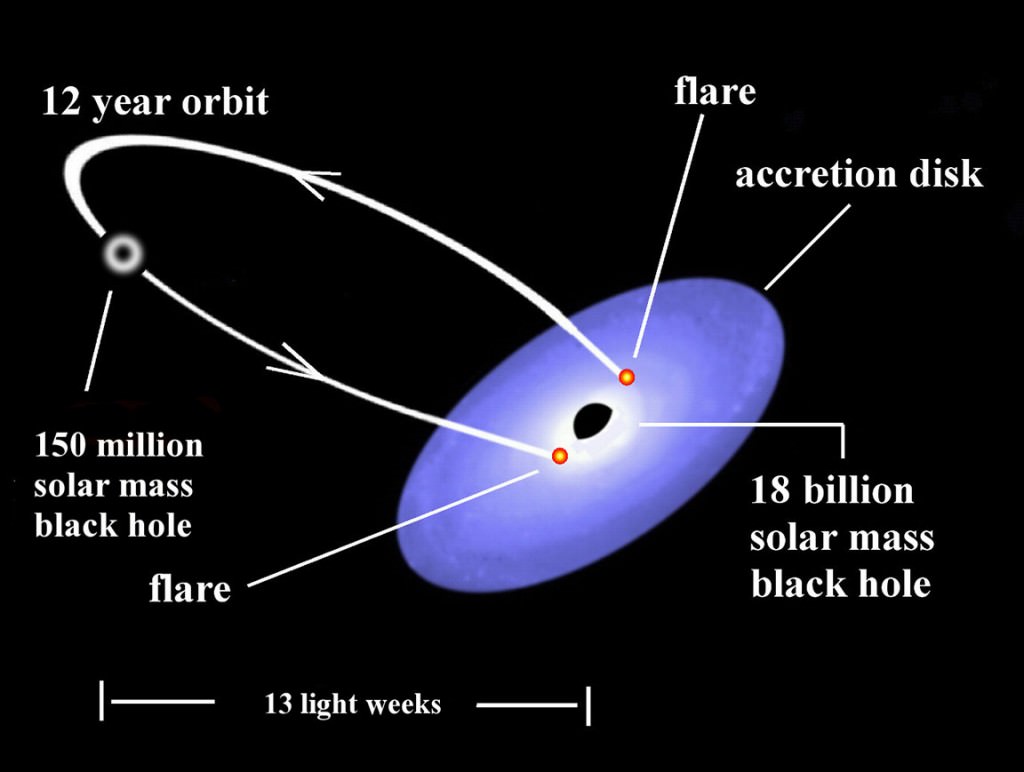

Regular stellar mass black holes aren’t the only ones that can collide. Supermassive black holes can collide too.

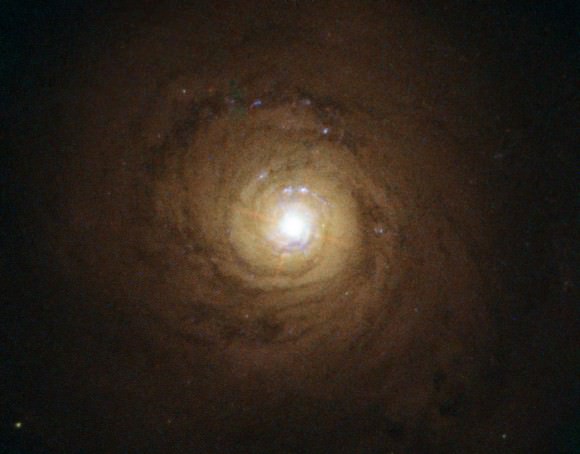

From what we can tell, there’s a supermassive black hole at the heart of pretty much every galaxy in the Universe. The one in the Milky Way is more than 4.1 million times the mass of the Sun, and the one at the heart of Andromeda is thought to be 110 to 230 million times the mass of the Sun.

In a few billion years, the Milky Way and Andromeda are going to collide, and begin the process of merging together. Unless the Milky Way’s black hole gets kicked off into deep space, the two black holes are going to end up orbiting one another.

Just with the stellar mass black holes, they’re going to radiate away angular momentum in the form of gravitational waves, and spiral closer and closer together. Some point, in the distant future, the two black holes will merge into an even more supermassive black hole.

The Milky Way and Andromeda will merge into Milkdromeda, and over the future billions of years, will continue to gather up new galaxies, extract their black holes and mashing them into the collective.

Black holes can absolutely collide. Einstein predicted the gravitational waves this would generate, and now LIGO has observed them for the first time. As better tools are developed, we should learn more and more about these extreme events.