Astronomers are pretty sure what happened after the Big Bang, but what came before? What are the leading theories for the causes of the Big Bang?

About 13.8 billion years ago the Universe started with a bang, kicked the doors in, brought fancy cheeses and a bag of ice, spiked the punch bowl and invited the new neighbors over for all-nighter to encompass all all-nighters from that point forward.

But what happened before that?

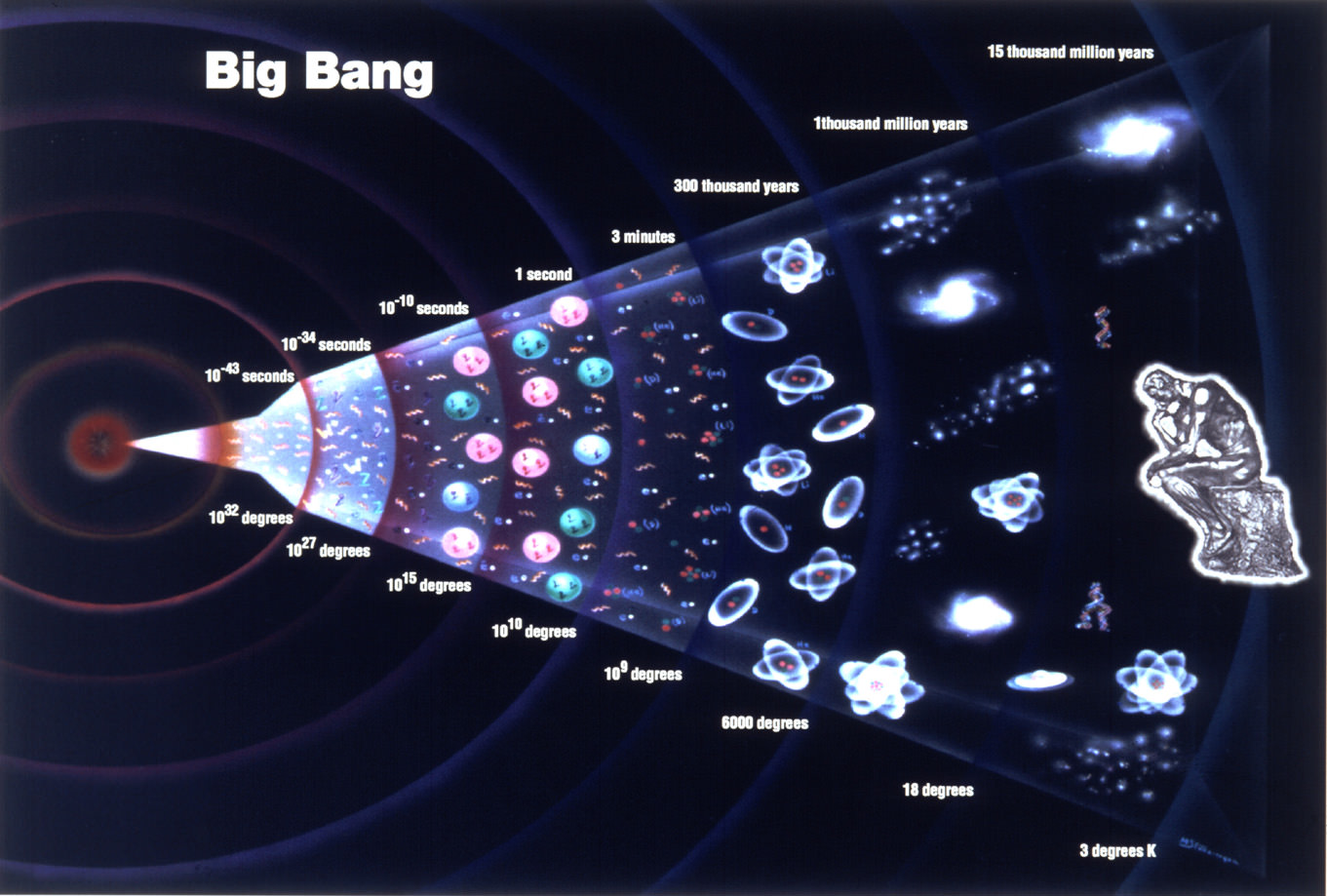

What was going on before the Big Bang? Usually, we tell the story of the Universe by starting at the Big Bang and then talking about what happened after. Similarly and completely opposite to how astronomers view the Universe… by standing in the present and looking backwards. From here, the furthest we can look back is to the cosmic microwave background, which is about 380,000 years after the big bang.

Before that we couldn’t hope to see a thing, the Universe was just too hot and dense to be transparent. Like pea soup. Soup made of delicious face burning high energy everything.

In traditional stupid earth-bound no-Tardis life unsatisfactory fashion, we can’t actually observe the origin of the Universe from our place in time and space.

Damn you… place in time and space.

Fortunately, the thinky types have come up with some ideas, and they’re all one part crazy, one part mind bendy, and 100% bananas. The first idea is that it all began as a kind of quantum fluctuation that inflated to our present universe.

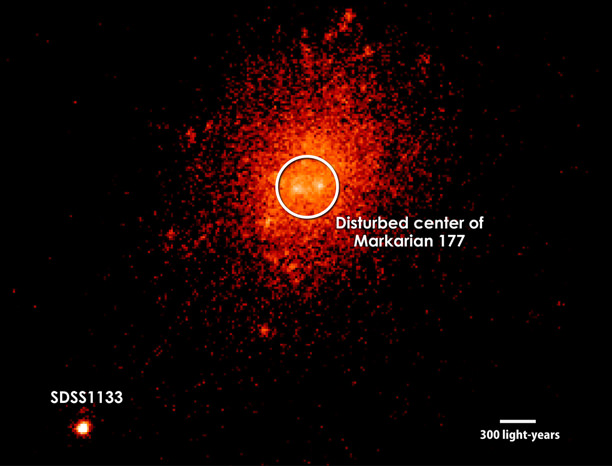

Something very, very subtle expanding over time resulting in, as an accidental byproduct, our existence. The alternate idea is that our universe began within a black hole of an older universe.

I’m gonna let you think about that one. Just let your brain simmer there.

There was universe “here”, that isn’t our universe, then that universe became a black hole… and from that black hole formed us and EVERYTHING around us. Literally, everything around us. In every direction we look, and even the stuff we just assume to be out there.

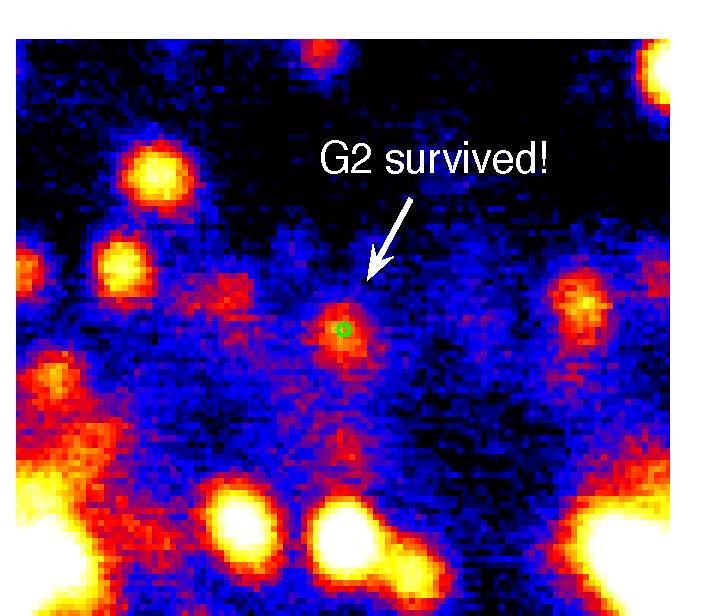

Here’s another one. We see particles popping into existence here in our Universe. What if, after an immense amount of time, a whole Universe’s worth of particles all popped into existence at the same time. Seriously… an immense amount of time, with lots and lots of “almost” universes that didn’t make the cut.

More recently, the BICEP2 team observed what may be evidence of inflation in the early Universe.

Like any claim of this gravity, the result is hotly debated. If the idea of inflation is correct, it is possible that our universe is part of a much larger multiverse. And the most popular form would produce a kind of eternal inflation, where universes are springing up all the time. Ours would just happen to be one of them.

It is also possible that asking what came before the big bang is much like asking what is north of the North Pole. What looks like a beginning in need of a cause may just be due to our own perspective. We like to think of effects always having a cause, but the Universe might be an exception. The Universe might simply be. Because.

You tell us. What was going on before the party started? Let us know in the comments below.

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!