Eclipsing binary star systems are relatively common in our Universe. To the casual observer, these systems look like a single star, but are actually composed of two stars orbiting closely together. The study of these systems offers astronomers an opportunity to directly measure the fundamental properties (i.e. the masses and radii) of these systems respective stellar components.

Recently, a team of Brazilian astronomers observed a rare sight in the Milky Way – an eclipsing binary composed of a white dwarf and a low-mass brown dwarf. Even more unusual was the fact that the white dwarf’s life cycle appeared to have been prematurely cut short by its brown dwarf companion, which caused its early death by slowly siphoning off material and “starving” it to death.

The study which detailed their findings, titled “HS 2231+2441: an HW Vir system composed by a low-mass white dwarf and a brown dwarf“, was recently published the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The team was led by Leonardo Andrade de Almeida, a postdoctoral fellow from the University of São Paolo’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences (IAG-USP), along with members from the National Institute for Space Research (MCTIC), and the State University of Feira de Santana.

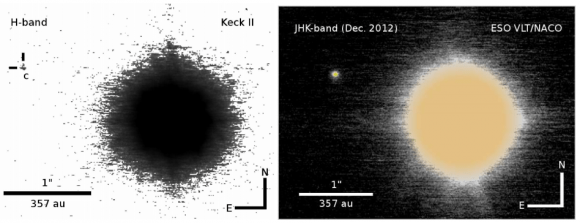

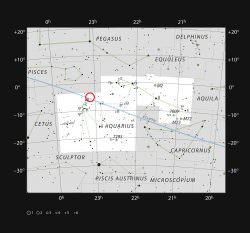

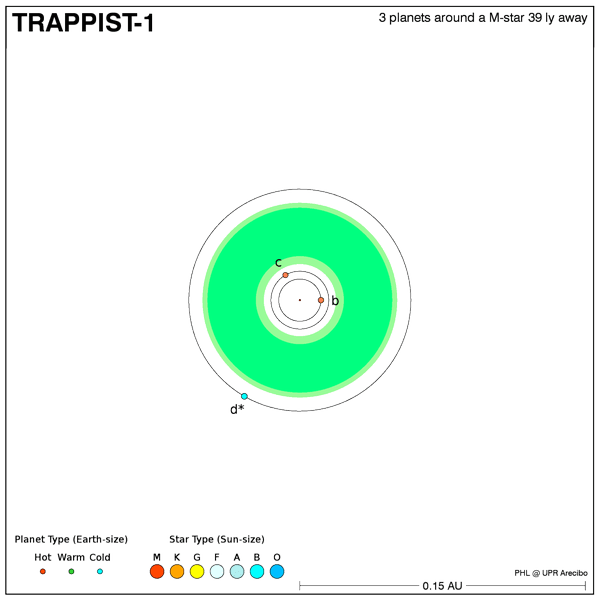

For the sake of their study, the team conducted observations of a binary star system between 2005 and 2013 using the Pico dos Dias Observatory in Brazil. This data was then combined with information from the William Herschel Telescope, which is located in the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos on the island of La Palma. This system, known as of HS 2231+2441, consists of a white dwarf star and a brown dwarf companion.

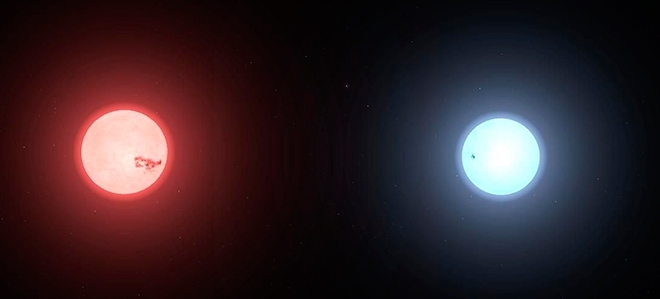

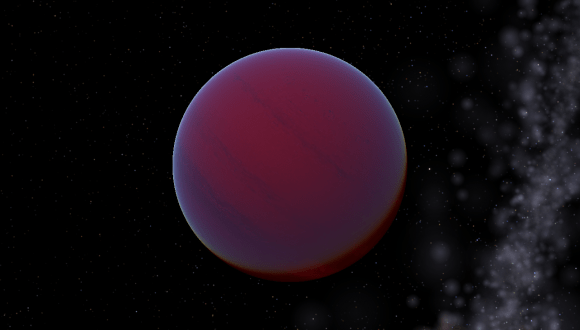

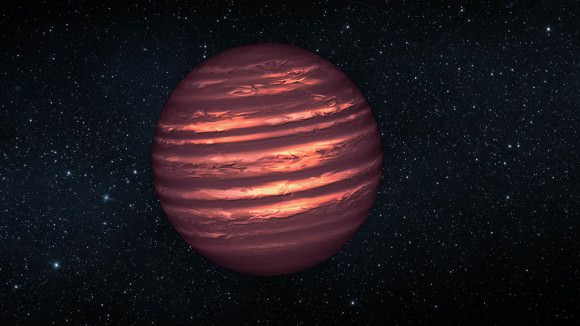

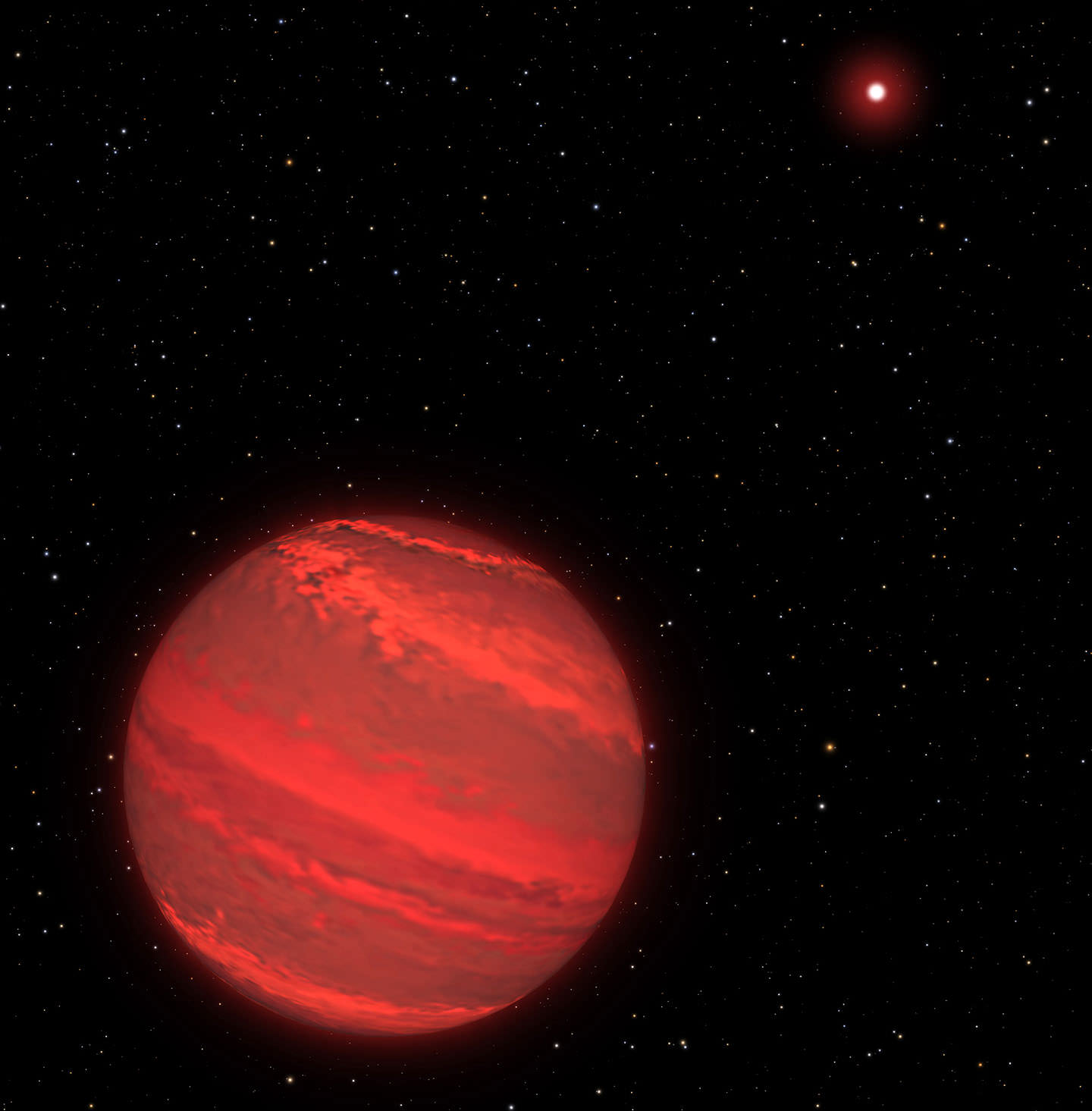

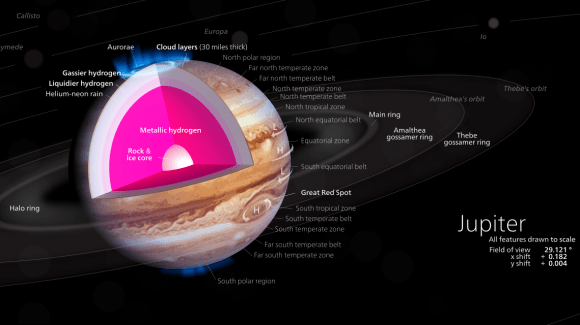

White dwarfs, which are the final stage of intermediate or low-mass stars, are essentially what is left after a star has exhausted its hydrogen and helium fuel and blown off its outer layers. A brown dwarf, on the other hand, is a substellar object that has a mass which places it between that of a star and a planet. Finding a binary system consisting of both objects together in the same system is something astronomers don’t see everyday.

As Leonardo Andrade de Almeida explained in a FAPESP press release, “This type of low-mass binary is relatively rare. Only a few dozen have been observed to date.”

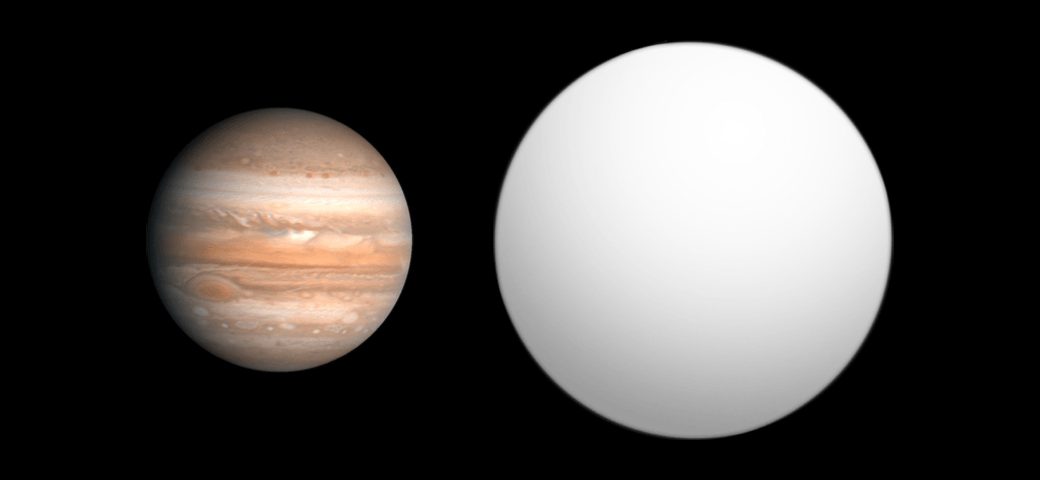

This particular binary pair consists of a white dwarf that is between twenty to thirty percent the Sun’s mass – 28,500 K (28,227 °C; 50,840 °F) – while the brown dwarf is roughly 34-36 times that of Jupiter. This makes HS 2231+2441 the least massive eclipsing binary system studied to date.

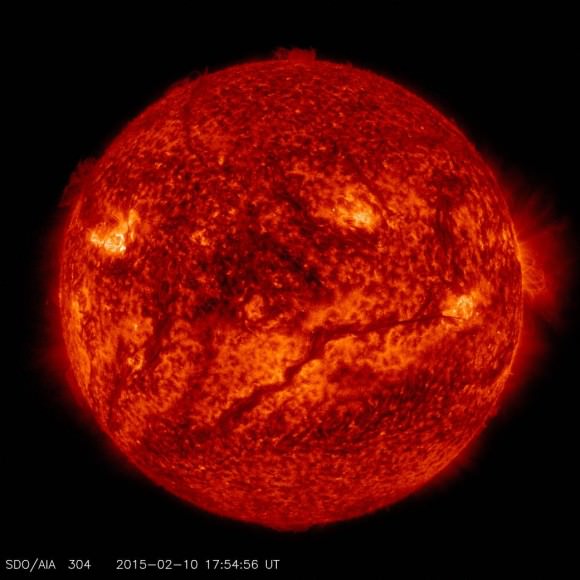

In the past, the primary (the white dwarf) was a normal star that evolved faster than its companion since it was more massive. Once it exhausted its hydrogen fuel, its formed a helium-burning core. At this point, the star was on its way to becoming a red giant, which is what happens when Sun-like stars exit their main sequence phase. This would have been characterized by a massive expansion, with its diameter exceeding 150 million km (93.2 million mi).

At this point, Almeida and his colleagues concluded that it began interacting gravitationally with its secondary (the brown dwarf). Meanwhile, the brown dwarf began to be attracted and engulfed by the primary’s atmosphere (i.e. its envelop), which caused it it lose orbital angular momentum. Eventually, the powerful force of attraction exceeded the gravitational force keeping the envelop anchored to its star.

Once this happened, the primary star’s outer layers began to be stripped away, exposing its helium core and sending massive amounts of matter to the brown dwarf. Because of this loss of mass, the remnant effectively died, becoming a white dwarf. The brown dwarf then began orbiting its white dwarf primary with a short orbital period of just three hours. As Almeida explained:

“This transfer of mass from the more massive star, the primary object, to its companion, which is the secondary object, was extremely violent and unstable, and it lasted a short time… The secondary object, which is now a brown dwarf, must also have acquired some matter when it shared its envelope with the primary object, but not enough to become a new star.”

This situation is similar to what astronomers noticed this past summer while studying the binary star system known as WD 1202-024. Here too, a brown dwarf companion was discovered orbiting a white dwarf primary. What’s more, the team responsible for the discovery indicated that the brown dwarf was likely pulled closer to the white dwarf once it entered its Red Giant Branch (RGB) phase.

At this point, the brown dwarf stripped the primary of its atmosphere, exposing the white dwarf remnant core. Similarly, the interaction of the primary with a brown dwarf companion caused premature stellar death. The fact that two such discoveries have happened within a short period of time is quite fortuitous. Considering the age of the Universe (which is roughly 13.8 billion years old), dead objects can only be formed in binary systems.

In the Milky Way alone, about 50% of low-mass stars exist as part of a binary system while high mass stars exist almost exclusively in binary pairs. In these cases, roughly three-quarters will interact in some way with a companion – exchanging mass, accelerating their rotations, and eventually en merging.

As Almeida indicated, the study of this binary system and those like it could seriously help astronomers understand how hot, compact objects like white dwarfs are formed. “Binary systems offer a direct way of measuring the main parameter of a star, which is its mass,” he said. “That’s why binary systems are crucial to our understanding of the life cycle of stars.”

It has only been in recent years that low-mass white dwarf stars were discovered. Finding binary systems where they coexist with brown dwarfs – essentially, failed stars – is another rarity. But with every new discovery, the opportunities to study the range of possibilities in our Universe increases.

Further Reading: São Paulo Research Foundation, MNRAS