[/caption]

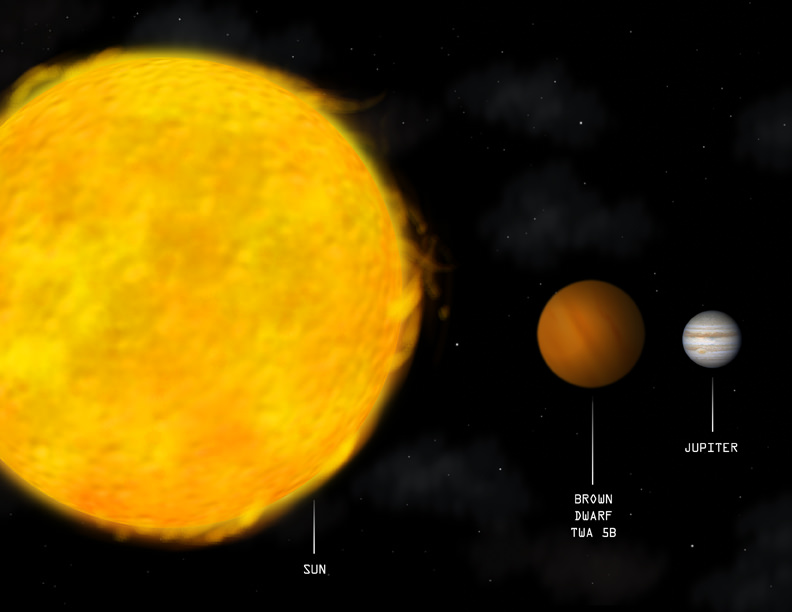

I feel a certain empathy for brown dwarfs. The first confirmed finding of one was only fifteen years ago and they remain frequently overlooked in most significant astronomical surveys. I mean OK, they can only (stifles laughter) burn deuterium but that’s something, isn’t it?

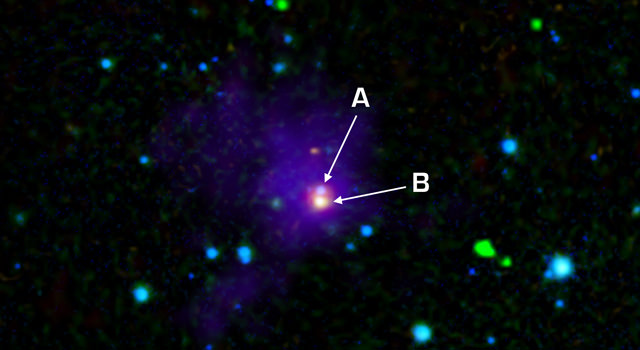

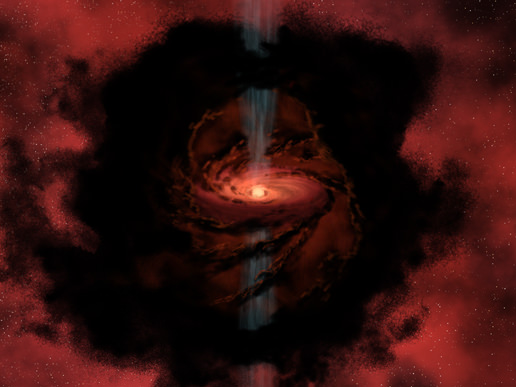

It has been suggested that a clever way of finding more brown dwarfs is in the radio spectrum. A brown dwarf with a strong magnetic field and a modicum of stellar wind should produce an electron cyclotron maser. Roughly speaking (something you can always depend on from this writer), electrons caught in a magnetic field are spun energetically in a tight circle, stimulating the emission of microwaves in a particular plane from the star’s polar regions. So you get a maser, essentially the microwave version of a laser, that would be visible on Earth – if we are in line of sight of it.

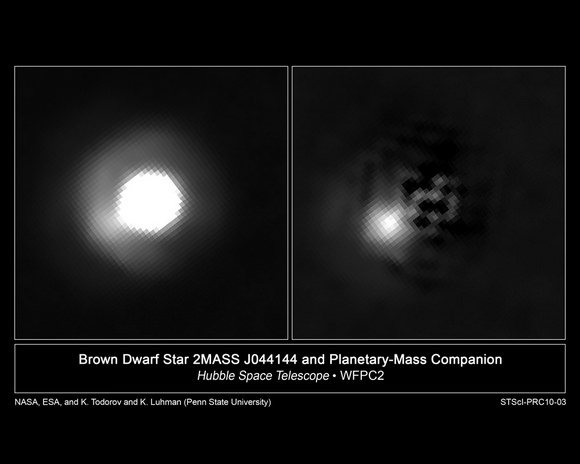

While the maser effect can probably be weakly generated by isolated brown dwarfs, it’s more likely we will detect one in binary association with a less mass-challenged star that is capable of generating a more vigorous stellar wind to interact with the brown dwarf’s magnetic field.

This maser effect is also proposed to offer a clever way of finding exoplanets. An exoplanet could easily outshine its host star in the radio spectrum if its magnetic field is powerful enough.

So far, searches for confirmed radio emissions from brown dwarfs or orbiting bodies around other stars have been unsuccessful, but this may become achievable in the near future with the steadily growing resolution of the European LOw Frequency ARray (LOFAR), which will be the best such instrument around until the Square Kilometer Array (SKA) is built – which won’t be seeing first light before at least 2017.

But even if we can’t see brown dwarfs and exoplanets in radio yet, we can start developing profiles of likely candidates. Christensen and others have derived a magnetic scaling relationship for small scale celestial objects, which delivers predictions that fit well with observations of solar system planets and low mass main sequence stars in the K and M spectral classes (remembering the spectral class mantra Old Backyard Astronomers Feel Good Knowing Mnemonics).

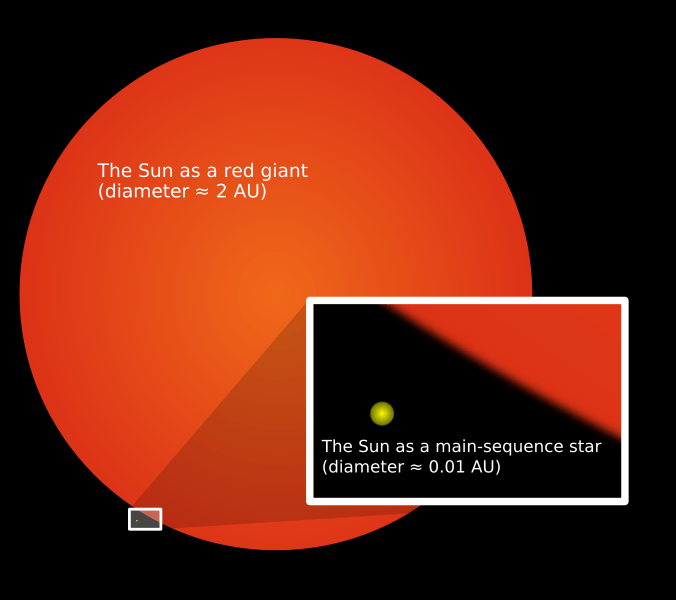

Using the Christensen model, it’s thought that brown dwarfs of about 70 Jupiter masses may have magnetic fields in the order of several kilo-Gauss in their first hundred million years of life, as they burn deuterium and spin fast. However, as they age, their magnetic field is likely to weaken as deuterium burning and spin rate declines.

Brown dwarfs with declining deuterium burning (due to age or smaller starting mass) may have magnetic fields similar to giant exoplanets, anywhere from 100 Gauss up to 1 kilo-Gauss. Mind you, that’s just for young exoplanets – the magnetic fields of exoplanets also evolve over time, such that their magnetic field strength may decrease by a factor of ten over 10 billion years.

In any case, Reiners and Christensen estimate that radio light from known exoplanets within 65 light years will emit at wavelengths that can make it through Earth’s ionosphere – so with the right ground-based equipment (i.e. a completed LOFAR or a SKA) we should be able to start spotting brown dwarfs and exoplanets aplenty.

Further reading: Reiners, A. and Christensen, U.R. (2010) A magnetic field evolution scenario for brown dwarfs and giant planets.