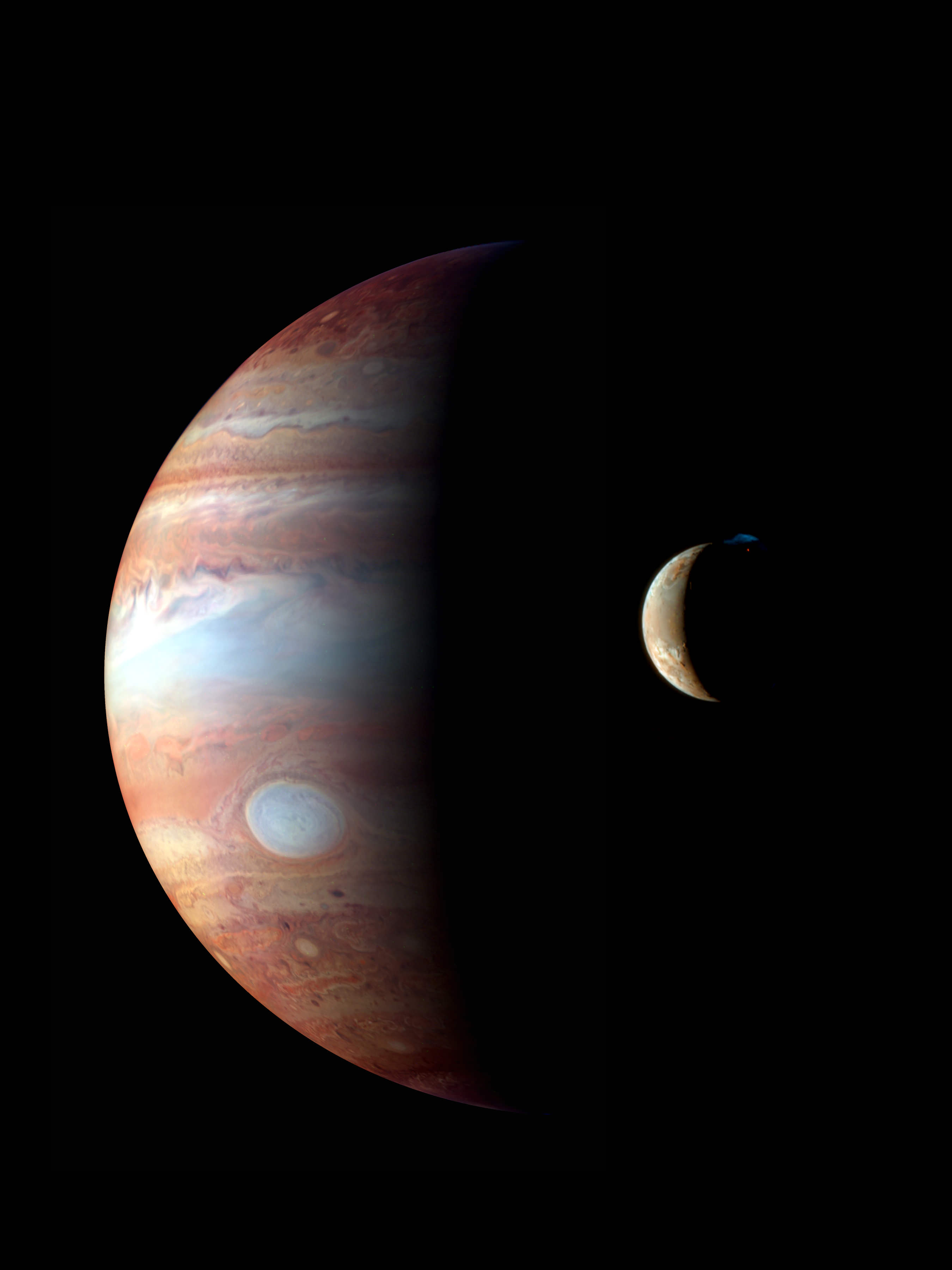

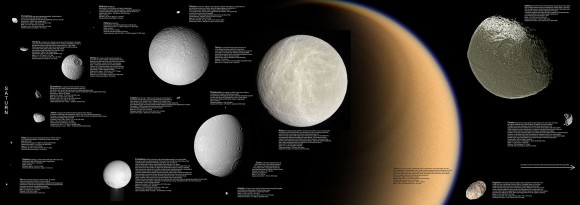

The Cronian system (i.e. Saturn and its system of rings and moons) is breathtaking to behold and intriguing to study. Besides its vast and beautiful ring system, it also has the second-most satellites of any planet in the Solar System. In fact, Saturn has an estimated 150 moons and moonlets – and only 53 of them have been officially named – which makes it second only to Jupiter.

For the most part, these moons are small, icy bodies that are believed to house interior oceans. And in all cases, particularly Rhea, their interesting appearances and compositions make them a prime target for scientific research. In addition to being able to tell us much about the Cronian system and its formation, moons like Rhea can also tell us much about the history of our Solar System.

Discovery and Naming:

Rhea was discovered by Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini on December 23rd, 1672. Together with the moons of Iapetus, Tethys and Dione, which he discovered between 1671 and 1672, he named them all Sidera Lodoicea (“the stars of Louis”) in honor of his patron, King Louis XIV of France. However, these names were not widely recognized outside of France.

In 1847, John Herschel (the son of famed astronomer William Herschel, who discovered Uranus, Enceladus and Mimas) suggested the name Rhea – which first appeared in his treatise Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope. Like all the other Cronian satellites, Rhea was named after a Titan from Greek mythology, the “mother of the gods” and one the sisters of Cronos (Saturn, in Roman mythology).

Size, Mass and Orbit:

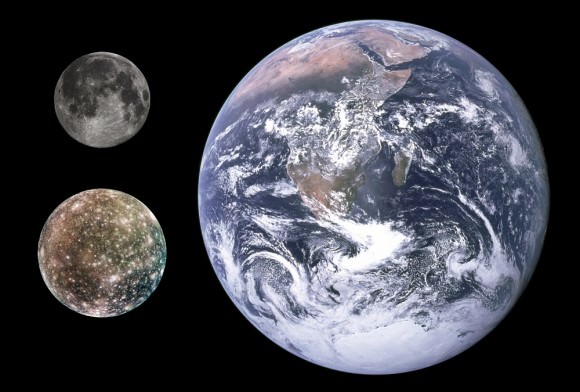

With a mean radius of 763.8±1.0 km and a mass of 2.3065 ×1021 kg, Rhea is equivalent in size to 0.1199 Earths (and 0.44 Moons), and about 0.00039 times as massive (or 0.03139 Moons). It orbits Saturn at an average distance (semi-major axis) of 527,108 km, which places it outside the orbits of Dione and Tethys, and has a nearly circular orbit with a very minor eccentricity (0.001).

With an orbital velocity of about 30,541 km/h, Rhea takes approximately 4.518 days to complete a single orbit of its parent planet. Like many of Saturn’s moons, its rotational period is synchronous with its orbit, meaning that the same face is always pointed towards it.

Composition and Surface Features:

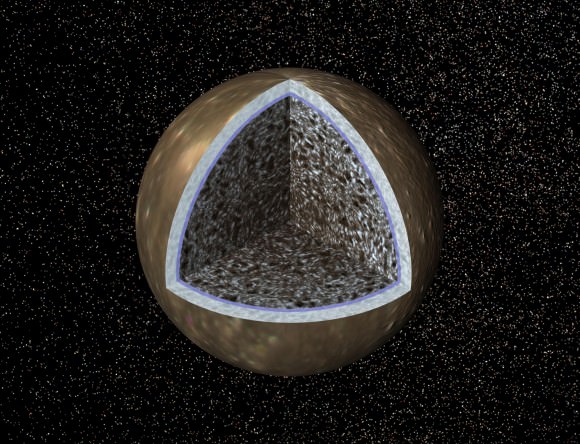

With a mean density of about 1.236 g/cm³, Rhea is estimated to be composed of 75% water ice (with a density of roughly 0.93 g/cm³) and 25% of silicate rock (with a density of around 3.25 g/cm³). This low density means that although Rhea is the ninth-largest moon in the Solar System, it is also the tenth-most massive.

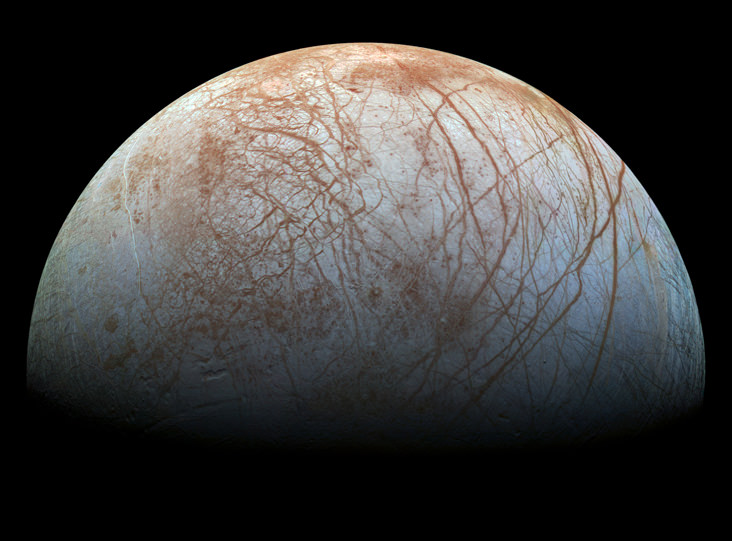

In terms of its interior, Rhea was originally suspected of being differentiated between a rocky core and an icy mantle. However, more recent measurements would seem to indicate that Rhea is either only partly differentiated, or has a homogeneous interior – likely consisting of both silicate rock and ice together (similar to Jupiter’s moon Callisto).

Models of Rhea’s interior also suggest that it may have an internal liquid-water ocean, similar to Enceladus and Titan. This liquid-water ocean, should it exist, would likely be located at the core-mantle boundary, and would be sustained by the heating caused by from decay of radioactive elements in its core.

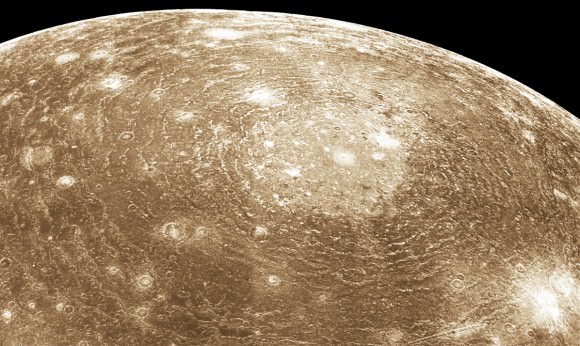

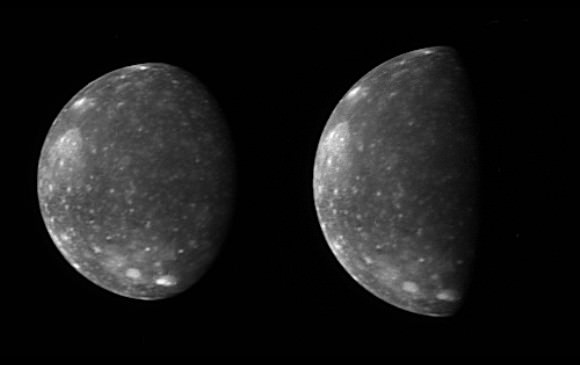

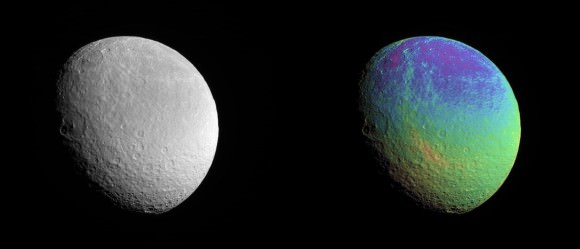

Rhea’s surface features resemble those of Dione, with dissimilar appearances existing between their leading and trailing hemispheres – which suggests that the two moons have similar compositions and histories. Images taken of the surface have led astronomers to divide it into two regions – the heavily cratered and bright terrain, where craters are larger than 40 km (25 miles) in diameter; and the polar and equatorial regions where craters are noticeably smaller.

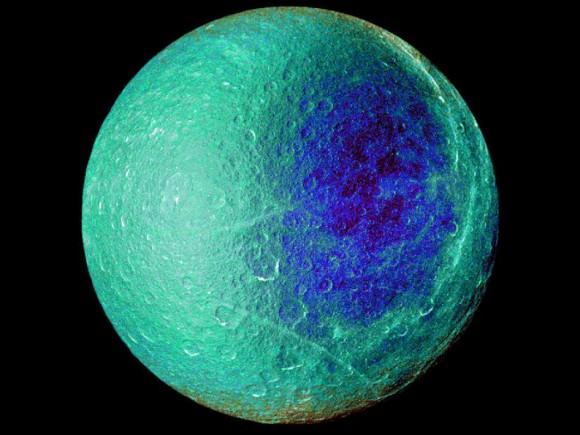

Another difference between Rhea’s leading and trailing hemisphere is their coloration. The leading hemisphere is heavily cratered and uniformly bright while the trailing hemisphere has networks of bright swaths on a dark background and few visible craters. It had been thought that these bright areas (aka. wispy terrain) might be material ejected from ice volcanoes early in Rhea’s history when its interior was still liquid.

However, observations of Dione, which has an even darker trailing hemisphere and similar but more prominent bright streaks, has cast this into doubt. It is now believed that the wispy terrain are tectonically-formed ice cliffs (chasmata) which resulted from extensive fracturing of the moon’s surface. Rhea also has a very faint “line” of material at its equator which was thought to be deposited by material deorbiting from its rings (see below).

Rhea has two particularly large impact basins, both of which are situated on Rhea’s anti-Cronian side (aka. the side facing away from Saturn). These are known as Tirawa and Mamaldi basins, which measure roughly 360 and 500 km (223.69 and 310.68 mi) across. The more northerly and less degraded basin of Tirawa overlaps Mamaldi – which lies to its southwest – and is roughly comparable to the Odysseus crater on Tethys (which gives it its “Death-Star” appearance).

Atmosphere:

Rhea has a tenuous atmosphere (exosphere) which consists of oxygen and carbon dioxide, which exists in a 5:2 ratio. The surface density of the exosphere is from 105 to 106 molecules per cubic centimeter, depending on local temperature. Surface temperatures on Rhea average 99 K (-174 °C/-281.2 °F) in direct sunlight, and between 73 K (-200 °C/-328 °F) and 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) when sunlight is absent.

The oxygen in the atmosphere is created by the interaction of surface water ice and ions supplied from Saturn’s magnetosphere (aka. radiolysis). These ions cause the water ice to break down into oxygen gas (O²) and elemental hydrogen (H), the former of which is retained while the latter escapes into space. The source of the carbon dioxide is less clear, and could be either the result of organics in the surface ice being oxidized, or from outgassing from the moon’s interior.

Rhea may also have a tenuous ring system, which was inferred based on observed changes in the flow of electrons trapped by Saturn’s magnetic field. The existence of a ring system was temporarily bolstered by the discovered presence of a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed along Rhea’s equator (which were interpreted as the impact points of deorbiting ring material).

However, more recent observations made by the Cassini probe have cast doubt on this. After taking images of the planet from multiple angles, no evidence of ring material was found, suggesting that there must be another cause for the observed electron flow and UV bright spots on Rhea’s equator. If such a ring system were to exist, it would be the first instance where a ring system was found orbiting a moon.

Exploration:

The first images of Rhea were obtained by the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft while they studied the Cronian system, in 1980 and 1981, respectively. No subsequent missions were made until the arrival of the Cassini orbiter in 2005. After it’s arrival in the Cronian system, the orbiter made five close targeted fly-bys and took many images of Saturn from long to moderate distances.

The Cronian system is definitely a fascinating place, and we’ve really only begun to scratch its surface in recent years. In time, more orbiters and perhaps landers will be traveling to the system, seeking to learn more about Saturn’s moons and what exists beneath their icy surfaces. One can only hope that any such mission includes a closer look at Rhea, and the other “Death Star Moon”, Dione.

We have many great articles on Rhea and Saturn’s system of moons here at Universe Today. Here is one about its possible ring system, its tectonic activity, it’s impact basins, and images provided by Cassini’s flyby.

Astronomy Cast also has an interesting interview with Dr. Kevin Grazier, who worked on the Cassini mission.

For more information, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration page on Rhea.