Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the “keel of the ship”, the Carina constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

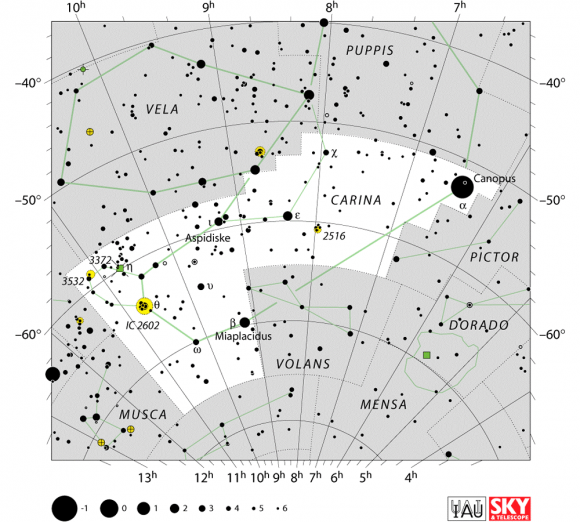

One of these constellations, known as Argo Navis, would eventually be divided into three asterism – one of which became the southern constellations of Carina. Bordered by the Vela, Puppis, Pictor, Volans, Chamaeleon, Musca and Centaurus constellations, Carina is one of 88 modern constellations that are currently recognized by the IAU.

Name and Meaning:

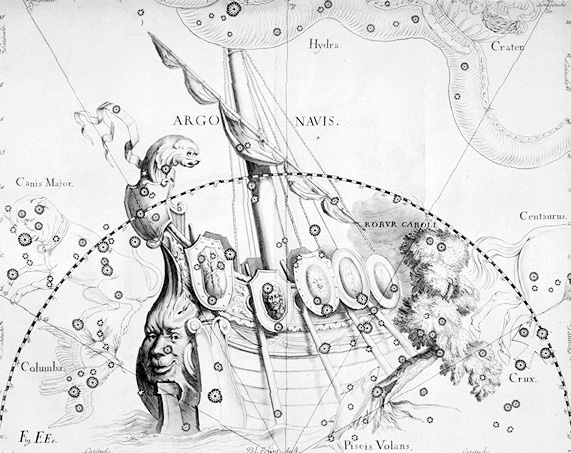

The stellar southern constellation Carina is part of the ancient constellation known as Argo Navis. It is now abbreviated and represents the “Keel”. While Carina has no real mythological connection, since its stars weren’t visible to the ancient Greeks and Romans, it does have a fascinating history. Argo Navis (or simply Argo) was a large southern constellation representing the Argo, the ship used by Jason and the Argonauts in Greek mythology.

The Argo was built by the shipwright Argus, and its crew were specially protected by the goddess Hera. The best source for the myth is the Argonautica by Apollonius Rhodius. According to a variety of sources of the legend, the Argo was said to have been planned or constructed with the help of Athena.

According to other legends it contained in its prow a magical piece of timber from the sacred forest of Dodona, which could speak and render prophecies. After the successful journey, the Argo was consecrated to Poseidon in the Isthmus of Corinth. It was then translated into the sky and turned into the constellation of Argo Navis. The abbreviation for it was “Arg”, and the genitive was “Argus Navis”.

History of Observation:

Carina is the only one of Ptolemy’s list of 48 constellations that is no longer officially recognized as a constellation. In 1752, French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille subdivided Argo Navis into Carina (the keel of the ship), Puppis (the Poop deck), and Vela (the sails). Were this still considered to be a single constellation, it would be the largest of all, being larger than Hydra.

When Argo Navis was split, its Bayer designations were also split. Whereas Carina got the Alpha, Beta and Epsilon stars, Vela got Gamma and Delta, Puppis got Zeta, and so on. The constellation Pyxis occupies an area which in antiquity was considered part of Argo’s mast. However, Pyxis is not typically considered part of Argo Navis, and in particular its Bayer designations are separate from those of Carina, Puppis and Vela.

Notable Features:

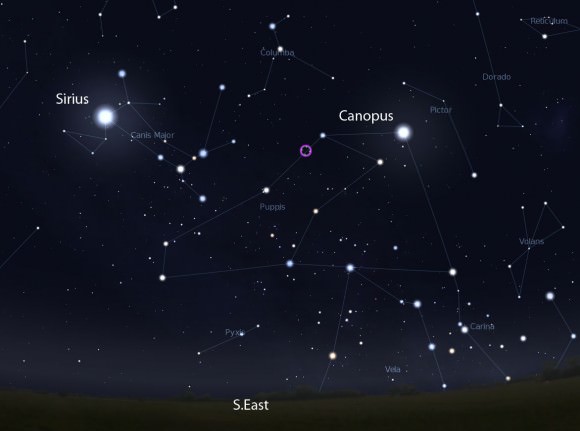

The Carina constellation consists of 9 primary stars and has 52 Bayer/Flamsteed designated stars. It’s alpha star, Canopus, is not only he brightest star in the constellation, but the second brightest in the night sky (behind Sirius). This F-type giant is 13,600 times brighter than our Sun, with an apparent visual magnitude of -0.72 and an absolute magnitude of -5.53.

The name is the Latinized version of the Greek name Kanobos, presumably derived from the pilot of the shop that took Menelaus of Sparta to Troy to retrieve Helen in The Iliad. It is also known by its Arabic name, Suhail, which is derived from the Arabic name for several bright stars.

Before the launching of the Hipparcos satellite telescope, distance estimates for the star varied widely, from 96 light years to 1200 light years. Had the latter distance been correct, Canopus would have been one of the most powerful stars in our galaxy. Hipparcos established Canopus as lying 310 light years (96 parsecs) from our solar system; this is based on a parallax measurement of 10.43 ± 0.53 mas.

The difficulty in measuring Canopus’ distance stemmed from its unusual nature. Canopus is too far away for Earth-based parallax observations to be made, so the star’s distance was not known with certainty until the early 1990s. Canopus is 15,000 times more luminous than the Sun and the most intrinsically bright star within approximately 700 light years.

For most stars in the local stellar neighborhood, Canopus would appear to be one of the brightest stars in the sky. Canopus is outshone by Sirius in our sky only because Sirius is far closer to the Earth (8 light years). Its surface temperature has been estimated at 7350 ± 30 K and its stellar diameter has been measured at 0.6 astronomical units 65 times that of the sun.

If it were placed at the centre of the solar system, it would extend three-quarters of the way to Mercury. An Earth-like planet would have to lie three times the distance of Pluto! Canopus is part of the Scorpius-Centaurus Association, a group of stars which share similar origins.

Next up is Miaplacidus (beta Carinae), an A-type subgiant located approximately 111 light years from Earth. It is the second brightest star in the constellation and the 29th brightest star in the sky. The star’s name means “placid waters”, which is derived from the combination of the Arabic word for waters (miyah) and the Latin word for placid (placidus).

Then there’s Eta Carinae, a luminous blue variable (LBV) binary star that is between 7,500 and 8,000 light years distant from Earth. The combined luminosity of this system is four million times that of our Sun, and the most massive star in the system has between 120 and 250 Solar Masses. It is sometimes known by its traditional names, Tseen She (“heaven’s altar” in Chinese) and Foramen.

Also, it is believed that Eta Carinae will explode in the not-too-distant future, and it will be the most spectacular supernovae humans have ever seen. This supernova (or hypernova) might even affect Earth, since the star is only 7,500 light years away, causing disruption to the upper layers of the atmosphere, the ozone layer, satellites, and spacecraft could be damaged and any astronauts who happen to be in space could be injured.

Avior (epsilon Carinae) is another double star system, consisting of a K0 III class orange giant and a hot hydrogen-fusing B2 V blue dwarf. With an apparent magnitude of 1.86 and is 630 light years distant, it is the 84th brightest star in the sky. The name Avior was assigned in the late 1930s by Her Majesty’s Nautical Almanac Office as a navigational aid, at the request of the Royal Air Force.

Aspidiske (aka. Iota Carinae) is a rare spectral type A8 Ib white supergiant located 690 light years from Earth. With a luminosity of 4,900 Suns (and seven Solar Masses), it is the 68th brightest star in the sky and is estimated to be around 40 million years old. It is known by the names Aspidiske, Turais and Scutulum, all diminutives of the word “shield,” (in Greek, Arabic and Latin, respectively).

Since the Milky Way runs through Carina, there are a large number of Deep Sky Objects associated with it. For instance, there’s the Carina Nebula (aka. the Eta Carinae Nebula, NGC 3372), a large nebula surrounding the massive stars Eta Carinae and HD 93129A. In addition to being four time as bright as the Orion Nebula (Messier 42), it is one of the largest diffuse nebulae known.

The nebula is between 6,500 and 10,000 light years from Earth, and has an apparent visual magnitude of 1.0. It contains several O-type stars (extremely luminous hot, bluish stars, which are very rare). The first recorded observation of this nebula was made by the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1751-52, who observed it from the Cape of Good Hope.

The Carina Nebula contains two smaller nebulae – the Homunculus Nebula and the Keyhole Nebula. The Keyhole Nebula – a small, dark cloud of dust and with bright filaments of fluorescent gas, was named by John Herschel in the 19th century. It is about seven light years in diameter, and appears contrasted against the bright nebula in the background.

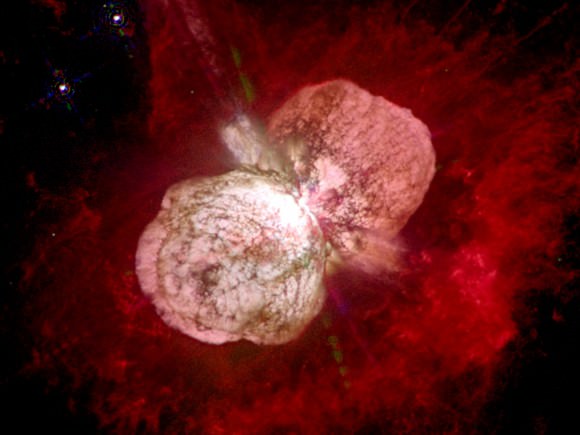

The Homunculus Nebula (Latin for “Little Man”) is an emission nebula embedded within the Eta Carinae Nebula, immediately surrounding the star Eta Carinae. The nebula is believed to have formed after an enormous outburst from the star, which coincided with Eta Carinae becoming the second brightest star in the night sky. The light of this outburst was visible from Earth by 1841.

There’s also the Theta Carinae Cluster (aka. the Southern Pleiades, because of its resemblance to the Pleiades cluster. This open cluster was discovered by Lacaille in 1751, is located approximately 479 light years from Earth and is visible to the naked eye. The brightest star in the cluster, as the name indicates, is Theta Carinae, a blue-white dwarf.

Then there’s the Wishing Well Cluster (aka. NGC 3532), an open cluster in Carina. Approximately 1,321 light years distant, the cluster is composed of about 150 stars that appear through a telescope like silver coins twinkling at the bottom of a wishing well. The cluster lies between the constellation Crux (the Southern Cross) and the False Cross asterism in Carina and Vela, and was first object observed by the Hubble Space Telescope in May 1990.

Finding Carina:

Carina is the 34th largest constellation in the sky, occupying an area of 494 square degrees. It lies in the second quadrant of the southern hemisphere (SQ2) and is visible at latitudes between +20° and -90° and is best seen during the month of March. Before you even begin with a telescope or binoculars, be sure to stop and just take a good look at Alpha Carinae – Canopus.

Canopus is essentially white when seen with the naked eye (though F-type stars are sometimes listed as “yellowish-white”). The spectral classification for Canopus is F0 Ia (Ia meaning “bright supergiant”), and such stars are rare and poorly understood; they are stars that can be either in the process of evolving to or away from red giant status. This in turn made it difficult to know how intrinsically bright Canopus is, and therefore how far away it might be.

Since the Milky Way runs through Carina, there are a large number of open clusters in the constellation, making it a binocular observing paradise. NGC 2516 is a magnitude 3.1 open cluster originally discovered by Abbe Lacaille in 1751 with a 1/2″ spyglass. This gorgeous 30 arc minute spread of stars is also known as Caldwell 96 and graces many observing lists, including the Astronomical League Open Cluster, Deep Sky and Southern Observing Clubs.

It is commonly known as the “Southern Beehive Cluster” (for it does resemble northern Messier 44) and it contains about 100 stars the brightest of which is an fifth magnitude red giant that lies near the center. As far as stellar age goes, this star cluster is very young – only about 140 million years old!

Now hop to IC 2602, popularly known as the “Southern Pleiades” for is resemblance to northern Messier 45. This galactic cluster contains more than 50 stars and is approximately 500 light years away from Earth. At its heart is blue-white star Theta Carinae, and it can be found by forming a triangle in the sky with Beta and Iota Carinae. With a stellar magnitude of 2.0, this object is easily seen as a nebulous patch to the unaided eye!

Another nebula that can been seen unaided but is better in binoculars is the Homunculus, an emission nebula surrounding the massive star Eta Carinae. The nebula is embedded within a much larger H II region, the Eta Carinae Nebula. Even though Eta Carinae is about 7,500 light-years away, structures only 10 billion miles across (about the diameter of our solar system) can be distinguished.

Dust lanes, tiny condensations, and strange radial streaks all appear with unprecedented clarity. Excess violet light escapes along the equatorial plane between the bipolar lobes. While there is relatively little dusty debris between the lobes down by the star; most of the blue light is able to escape. The lobes, on the other hand, contain large amounts of dust which absorb blue light, causing the lobes to appear reddish.

The Eta Carinae Nebula, or NGC 3372 itself is fascinating. It is a hypergiant luminous blue variable star in the Carina constellation, one of the most massive stars yet discovered. Because of its mass and the stage of life, it is expected to explode in a supernova in the “near” future. Stars in the stellar mass class of Eta Carinae, with more than 100 times the mass of the Sun, produce more than a million times as much light as the Sun.

They are quite rare — only a few dozen in a galaxy as big as the Milky Way. They are assumed to approach (or potentially exceed) the Eddington limit, i.e., the outward pressure of their radiation is almost strong enough to counteract gravity. Stars that are more than 120 solar masses exceed the theoretical Eddington limit, and their gravity is barely strong enough to hold in their radiation and gas.

Now hop just three degrees away to NGC 3532 – known as the “Wishing Well Cluster”. This open star cluster is one of the jewels of the southern sky and is also referred to as Caldwell 91 and is on many observing lists. Want another? Try globular cluster NGC 2808, also known as Bennett 41. Beautiful NGC 2808 is a fine example of a symmetrical and strongly compressed globular cluster.

Viewable in binoculars and totally resolvable in a 6″ telescope, this is another of Dreyer’s remarkable objects described as very large extremely rich, and gradually reaching an extremely condensed status in the middle. NGC 2808 contains thousands of magnitude 13-15 stars!

For double star fans, take on Epsilon Carinae, also known by the name Avior. Epsilon Carinae is a binary star located 630 light years away from our solar system. The primary component is a dying orange giant of spectral class K0 III, and the secondary is a hot hydrogen-fusing blue dwarf of class B2 V. The stars regularly eclipse each other, leading to brightness fluctuations on the order of 0.1 magnitudes.

Now try Upsilon Carinae – part of the Diamond Cross asterism in southern Carina. It’s name is Vathorz Prior, a name of Old Norse-Latin origin meaning “Preceding One of the Waterline”. Located approximately 1623 light years from Earth, the star system is made of two components. Upsilon Carinae A, is a white A-type supergiant with an apparent magnitude of +3.01 while its companion, Upsilon Carinae B, is a blue-white B-type giant 5 arc seconds away.

But no constellation would be complete without a true telescope challenge. Planetary nebula NGC 3211 (RA 10h 17m 50.4s Dec -62° 40´ 12″) heralds in at about 12th magnitude. For even more fun, try NGC 2867 (R.A. 09h 21m 25.3s Dec. -58° 18′ 40.7″). You’ll find it about a degree north/northeast of Iota. Iota Carinae. NGC 2867 may be no more than 2,750 years old.

Strangely, it is one of only a few dozen objects known to have a Wolf-Rayet star (type WC6) as its central star. NGC 2867 was discovered by John Herschel from Felhausen observatory at the Cape of Good Hope on April’s Fools Day, 1834 – appropriate since Herschel was almost fooled into thinking it was a new planet. Its size and appearance were certainly planet-like and it was only after careful checking that Herschel was convinced it was a nebula.

Now try NGC 3247 (RA 10 : 25.9 Dec -57 : 56 ). This is a very cool, very small galactic cluster with associated nebulosity. At around magnitude 8, you won’t find the rich little cluster much of a problem, but use minimal magnifcation to appreciate the true field!

While at the telescope, also look up NGC 3059 (9 : 50.2 Dec -73 : 55). Now, we’ve got a spiral galaxy cutting its way through the dust of the Milky Way! With an apparent magnitude of 12, and a 3.2 arc minute diameter, this barred spiral galaxy is going to present a nice, unique challenge to southern hemisphere observers.

There are myriad other things to look at in Carina as well, so don’t see this lovely constellation short! There is also a meteor shower associated with the constellation of Carina, too. The Eta Carinids are a lesser known meteor shower lasting from January 14 to 27 each year. The activity peaks on or about January 21. It was first discovered in 1961 in Australia. Roughly two to three meteors occur per hour at its maximum. It gets its name from the radiant which is close to the nebulous star Eta Carinae.

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Source: