For almost two decades, NASA’s Earth Observatory has provided a constant stream of information about the Earth’s climate, water cycle, and meteorological patterns. This information has allowed scientists to track weather systems, map urban development and agriculture, and monitor for changes in the atmosphere. This has been especially important given the impact of Anthropogenic Climate Change.

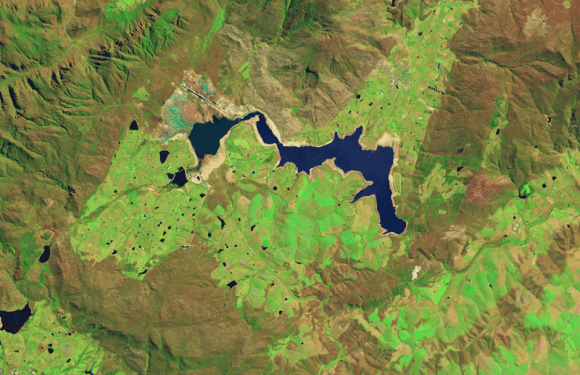

Consider the animation recently released by the Earth Observatory, which show how the city of Cape Town, South Africa has been steadily depleting its supply of fresh water over the past few years. Based on multiple sources of data, this illustration and the images it is based on show how urbanization, over-consumption, and changes in weather patterns around Cape Town are leading to a water crisis.

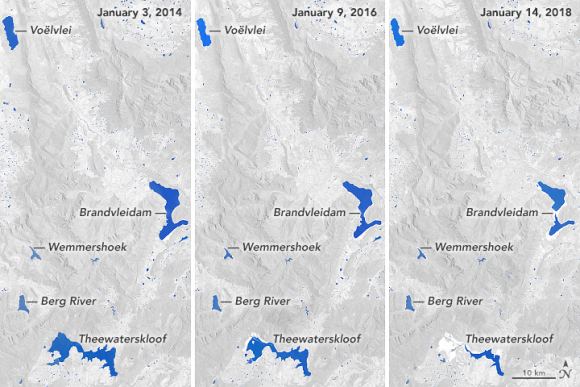

These images that make up this animation are partly based on satellite data of Cape Town’s six major reservoirs, which was acquired between January 3rd, 2014, and January 14th, 2018. Of these six reservoirs, the largest is the Theewaterskloof Dam, which has a capacity of 480 billion liters (126.8 billion gallons) and accounts for about 41% of the water storage capacity available to Cape Town.

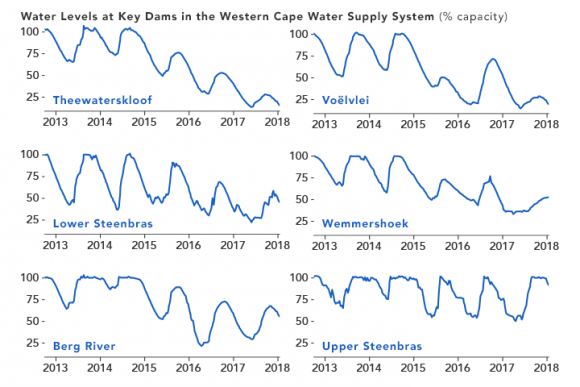

All told, these damns collectively store up to 898,000 megaliters (230 billion gallons) of water for Cape Town’s four million people. But according to data provided by NASA Earth Observatory, Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and water level data from South Africa’s Department of Water and Sanitation, these reservoirs have been seriously depleted thanks an ongoing drought in the region.

As you can see from the images (and from the animation above), the reservoirs have been slowly shrinking over the past few years. The extent of the reservoirs is shown in blue while dry areas are represented in grey to show how much their water levels have changed. While the decrease is certainly concerning, what is especially surprising is how rapidly it has taken place.

In 2014, Theewaterskloof was near full capacity, and during the previous year, the weather station at Cape Town airport indicated that the region experienced more rainfall than it had seen in decades. Over 682 millimeters (27 inches) of rain was reported in total that year, whereas 515 mm (20.3 in) is considered to be a normal annual rainfall for the region.

However, the region began to experience a drought in 2015 as rainfall faltered to just 325 mm (12.8 in). The next year was even worse with 221 mm (8.7 in); and in 2017, the station recorded just 157 mm (6.2 in) of rain. As of January 29th, 2018, the six reservoirs were at just 26% of their total capacity and Theewaterskloof Dam was in the worst shape, with just 13% of its capacity.

Naturally, this is rather dire news for Cape Town’s 4 million residents, and has led to some rather stark predictions. According to a recent statement made by the mayor of Cape Town, if current consumption patterns continue then the city’s disaster plan will have to be enacted. Known as Day Zero, this plan will go into effect when the city’s reservoirs reach 13.5% of capacity, and will result in water being turned off for all but hospitals and communal taps.

At this point, most people in the city will be left without tap water for drinking, bathing, or other uses and will be forced to procure water from some 200 collection points throughout the city. At present, Day Zero is expected to happen on April 12th, depending on weather patterns and consumption in the coming months.

Ordinarily, the rainy season last from May to September, and the implementation of Day Zero will depend on the level of rainfall. By the end of January, farmers will also stop drawing from the system for irrigation, meaning that water supplies prior to the rainy season could be stretched a little longer.

This is not the first time that Cape Town has been faced with the prospect of a Day Zero. Back in May of 2017, the city was declared a disaster area as the annual rainfall proved to be less than hoped for. This led to the province instituting the Disaster Management Act, which gives the provincial government the power to re-prioritize funding and enact conservation measures to preserve water in preparation for the dry season.

By the following September, Cape Town authorities released a series of guidelines for water usage that banned the use of all drinking water for non-essential purposes and urged people to use less than 87 liters (23 gallons) of water per person, per day. At the same time, authorities indicated that they were pursuing efforts to increase the supply of water by recycling, establish new desalinization facilities, and drill for new sources of groundwater.

But with the drought going into it’s fourth year, there is once again fear that the water crisis is not going to end anytime soon. According to an analysis performed by Piotr Wolski, a hydrologist at the Climate Systems Analysis Group at the University of Cape Town, this sort of pattern is something that happens every 1000 years or so. This conclusion was based on rainfall patterns dating back to 1923.

However, population growth and a lack of new infrastructure in the region has made the current water crisis what it is. Between 1995 and 2018, the population of Cape Town grew by roughly 80% while the capacity of the region’s dams grew by just 15%. However, the current predicament has accelerated plans to increase the water supply by creating new infrastructure and diverting water from the Berg River to the Voëlvlei Dam (now scheduled for completion by 2019).

For people living in many other parts of the world this story is a very familiar one. This includes California, which has been experiencing annual droughts since 2012; and southern India, which was hit by the worst drought in decades in 2016. All over the planet, growing populations and over-consumption are combining with shifting weather patterns and environmental impact to create a growing water crisis.

But as the saying goes, “necessity is the mother of invention”. And there’s nothing like an impending crisis to make people take stock of a problem and look for solutions!

Further Reading: NASA Earth Observatory