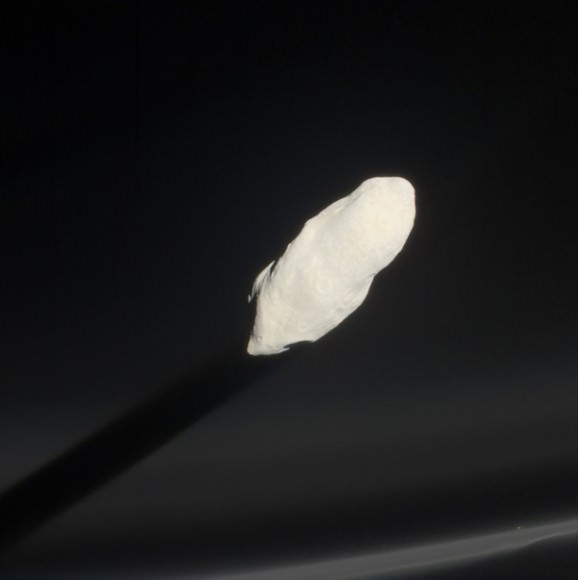

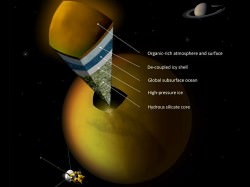

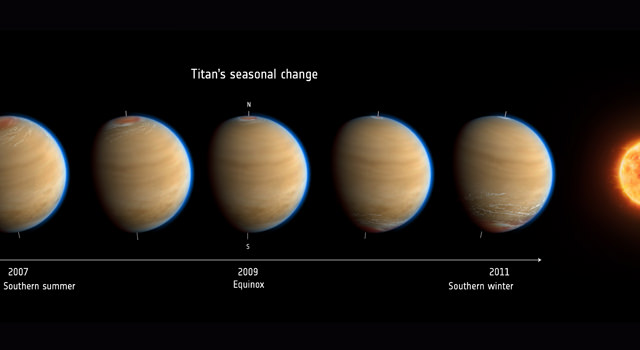

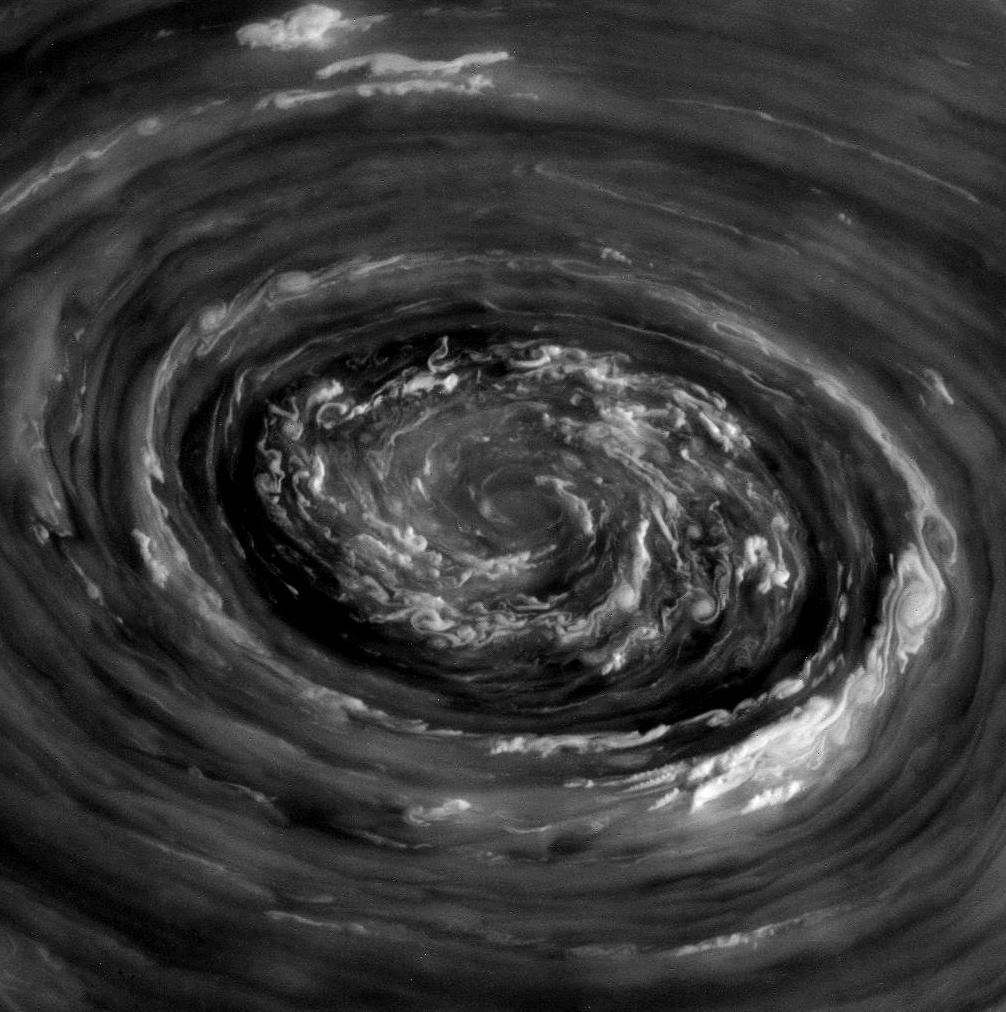

This artist’s impression of Saturn’s moon Titan shows the change in observed atmospheric effects before, during and after equinox in 2009. The Titan globes also provide an impression of the detached haze layer that extends all around the moon (blue). This image was inspired by data from NASA’s Cassini mission. Image Credit: ESA

A certain slant, or shift, of light glinting off of Saturn’s moon Titan turns out to drive unexpected reversals in the moon’s atmosphere according to data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

In a paper released in the November 28, 2012 issue of the journal Nature, scientists say in a press release that data from Cassini show evidence for sinking air where upwelling currents were seen earlier in the mission.

“Cassini’s up-close observations are likely the only ones we’ll have in our lifetime of a transition like this in action,” said Nick Teanby, the study’s lead author who is based at the University of Bristol, England, and is a Cassini team associate. “It’s extremely exciting to see such rapid changes on a body that usually changes so slowly and has a ‘year’ that is the equivalent of nearly 30 Earth years.”

Of the eight planets and dozens of moons in our solar system, just Earth, Venus, Mars and Titan have both a solid surface and a substantial atmosphere.

Cassini offers scientists a unique perspective during this change of seasons. The pole experiencing winter is typically pointed away from Earth because of its orbit around Saturn. Cassini provides scientists a platform to watch the atmosphere change over time and study the moon from angles impossible from Earth. It arrived at the ringed planet in 2004. Models of Titan’s atmosphere have predicted changes for two decades but Cassini is just now seeing new circulation patterns arise.

“Understanding Titan’s atmosphere gives us clues for understanding our own complex atmosphere,” said Scott Edgington, Cassini deputy project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “Some of the complexity in both places arises from the interplay of atmospheric circulation and chemistry.”

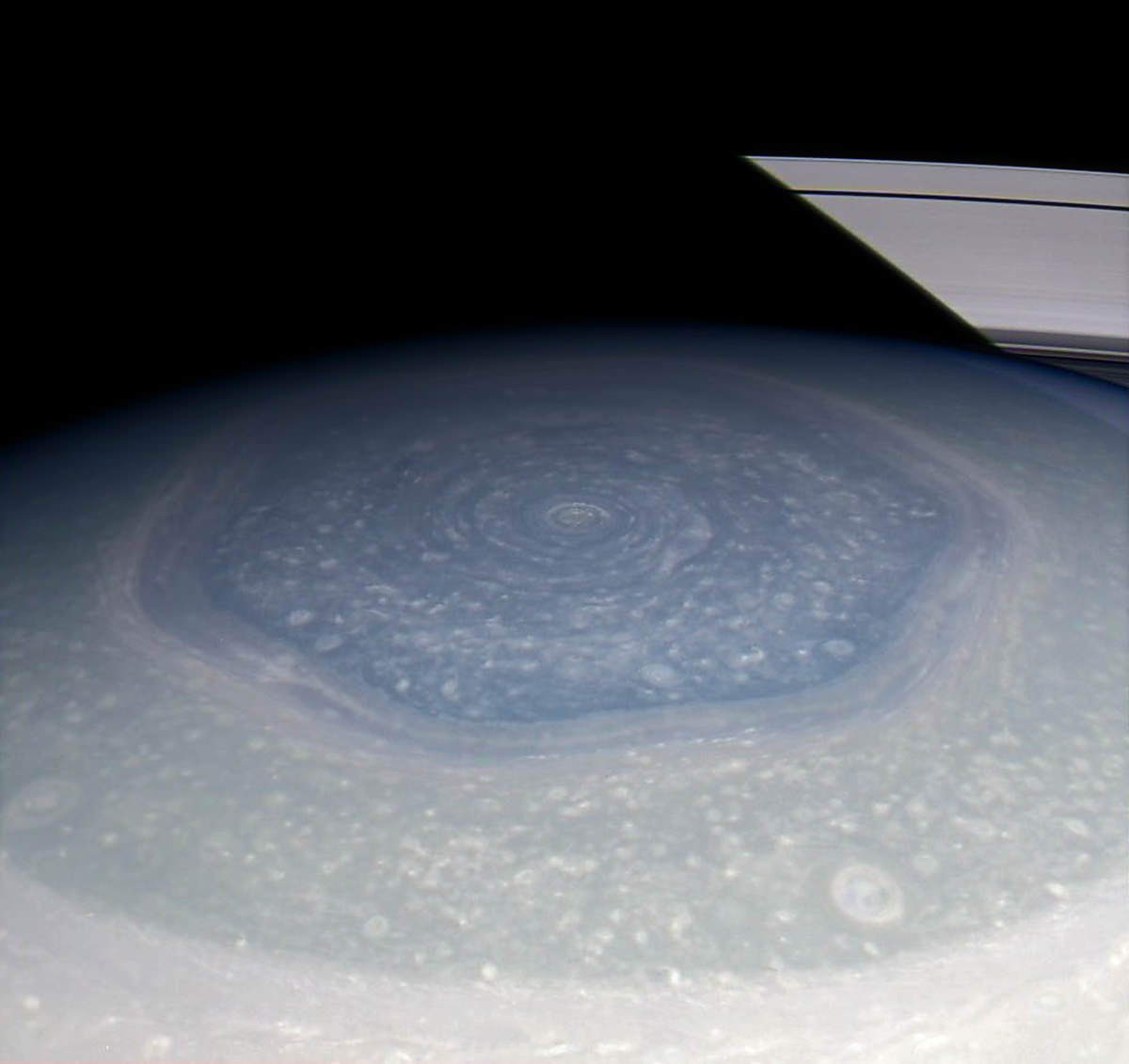

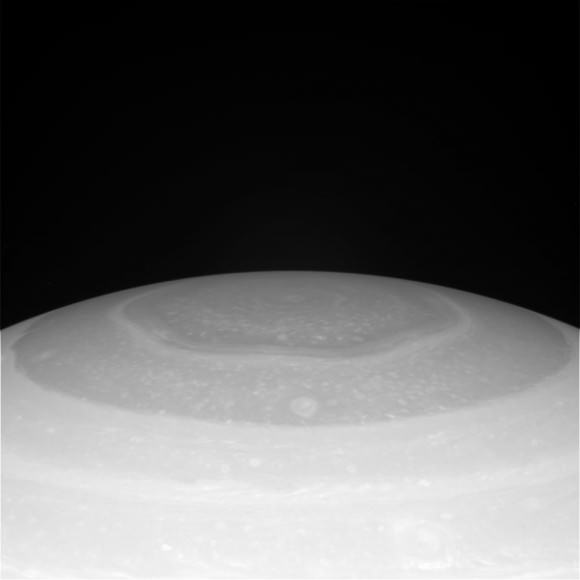

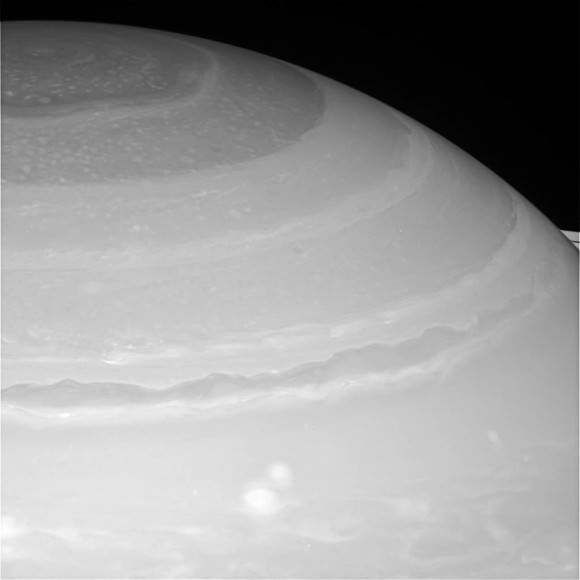

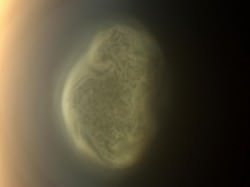

While scientists recently have watched the formation of haze and a vortex over Titan’s south pole, other Cassini instruments, such as the composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS), have gathered data tied more to the circulation and chemistry of Titan’s orangish atmosphere especially at higher altitudes. The CIRS instrument also reveals subtle changes in vertical winds and global circulation. The instrument shows that atmospheric circulation extends about 100 km, or 60 miles, higher than expected. This is important in explaining the orangish tint to Titan’s atmosphere. A haze layer, first detected by Voyager 1, may be a region rich in small haze particles that combine to form larger aggregates that descend deep into the atmosphere giving the moon its characteristic color.

While scientists recently have watched the formation of haze and a vortex over Titan’s south pole, other Cassini instruments, such as the composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS), have gathered data tied more to the circulation and chemistry of Titan’s orangish atmosphere especially at higher altitudes. The CIRS instrument also reveals subtle changes in vertical winds and global circulation. The instrument shows that atmospheric circulation extends about 100 km, or 60 miles, higher than expected. This is important in explaining the orangish tint to Titan’s atmosphere. A haze layer, first detected by Voyager 1, may be a region rich in small haze particles that combine to form larger aggregates that descend deep into the atmosphere giving the moon its characteristic color.

Scientists have narrowed down the atmospheric reversal to about six months near the August 2009 equinox when the Sun was shining directly on Titan’s equator.

“Next, we would expect to see the vortex over the south pole build up,” said Mike Flasar, the CIRS principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “As that happens, one question is whether the south winter pole will be the identical twin of the north winter pole, or will it have a distinct personality? The most important thing is to be able to keep watching as these changes happen.”

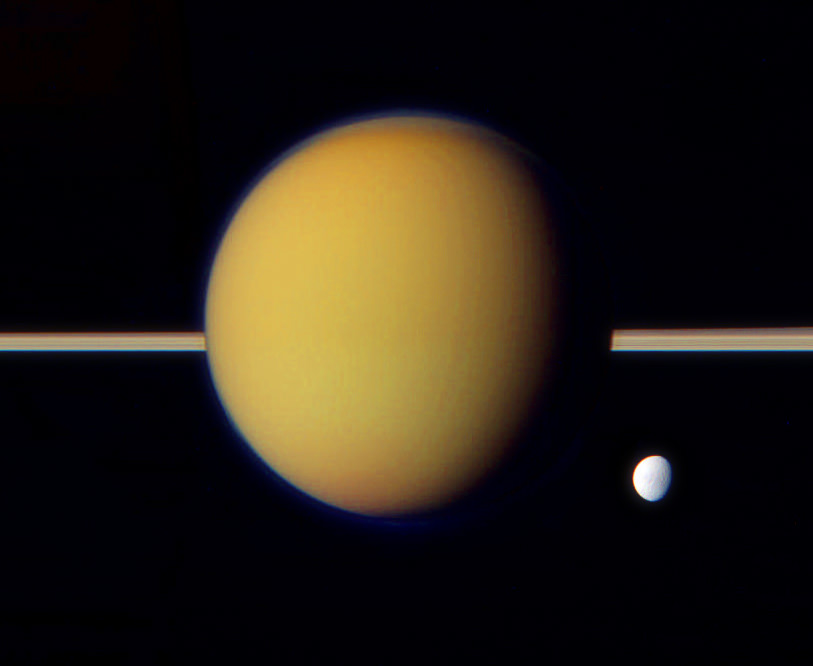

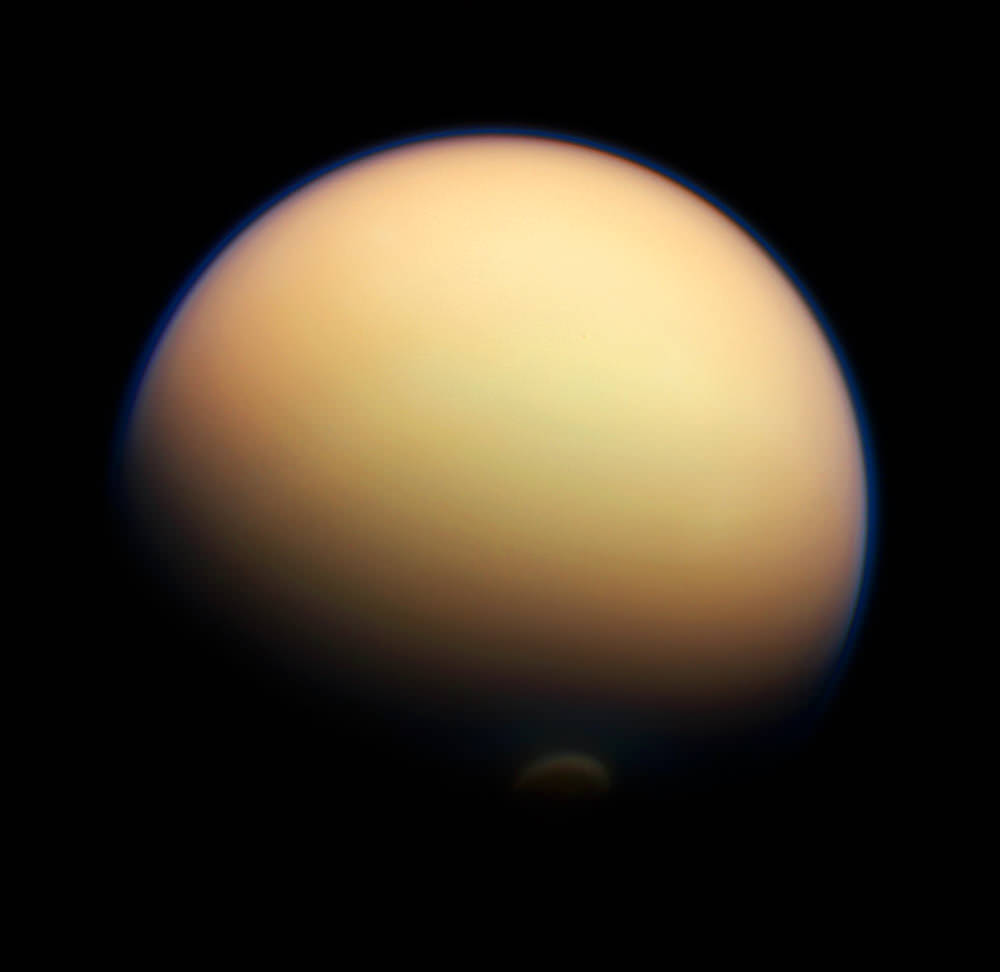

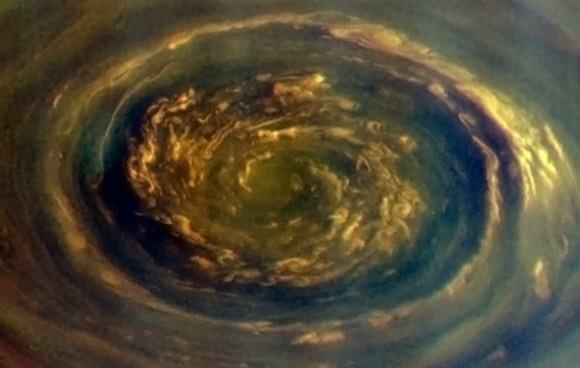

Second image caption: This true color image captured by NASA’S Cassini spacecraft before a distant flyby of Saturn’s moon Titan on June 27, 2012, shows a south polar vortex, or a swirling mass of gas around the pole in the atmosphere. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Source: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory