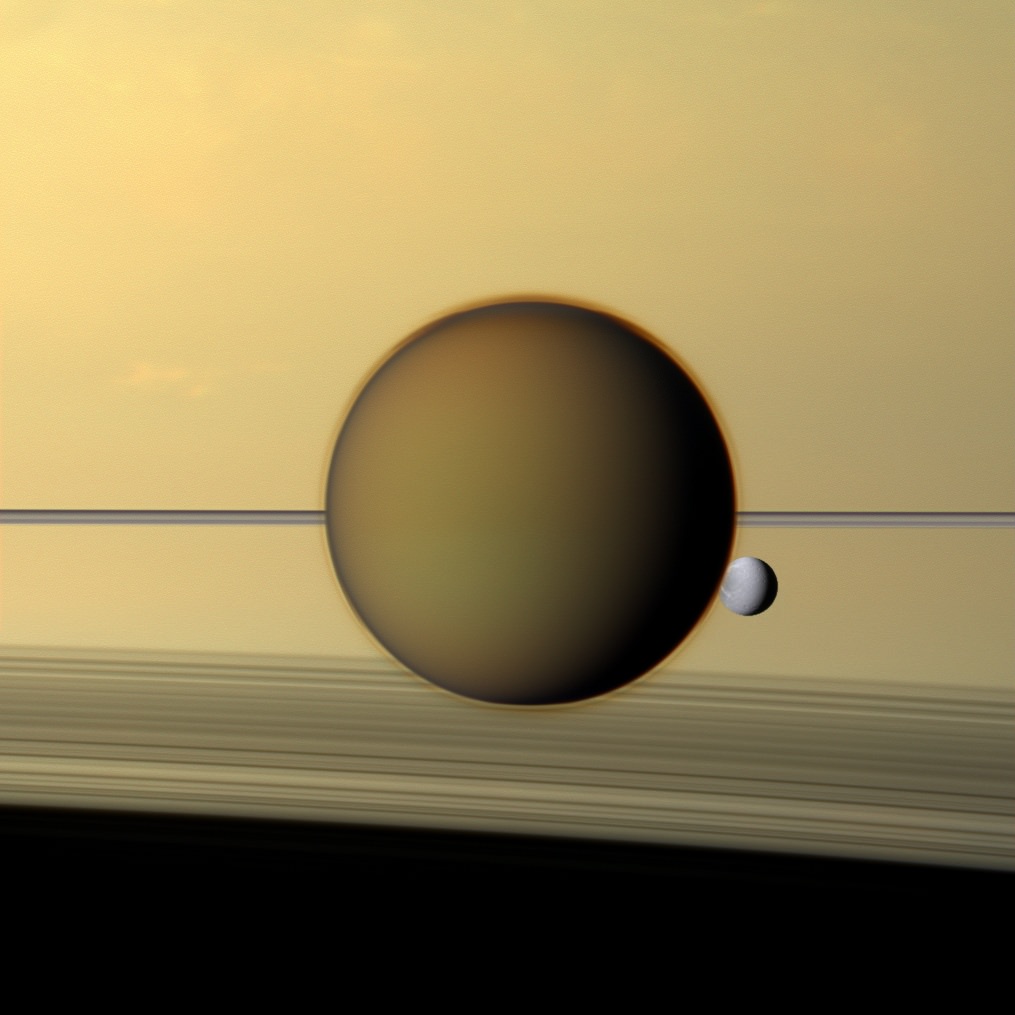

We’ve seen avalanches on Mars, but now scientists have found avalanches taking place on an unlikely place in our solar system: Saturn’s walnut-shaped, two-toned moon Iapetus. And these aren’t just run-of-the-mill avalanches: they are huge inundations of debris. These events are specifically known as long-runout landslides — debris flows that have traveled unusually long distances. Just how these avalanches are occurring is somewhat of a mystery, according to Bill McKinnon from Washington University in St. Louis.

“This is really about the mystery of long-runout landslides, and no one really knows for sure what causes them,” said McKinnon, speaking at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference this week.

These avalanches or landslides certainly have their Earthly counterparts and, as noted, similar events are found on Mars, where they are especially associated with the steep canyon walls of the Valles Marineris system. However, the large mass movements on Iapetus in the form of long-runout landslides are less common.

McKinnon said the amount of material that has been moved in all the avalanches on Iapetus that he and his team have found exceeds all the material moved in known Martian landslides (in published data), even though Mars is much bigger than Iapaetus.

“The mechanics of long-runout landslides are poorly understood, and mechanisms proposed for friction reduction are so numerous I can’t fit them all on one Powerpoint slide,” McKinnon said during his talk. Possible explanations include water (such as released groundwater), wet or saturated soil, ice, trapped or compressed air, acoustic fluidization, and more.

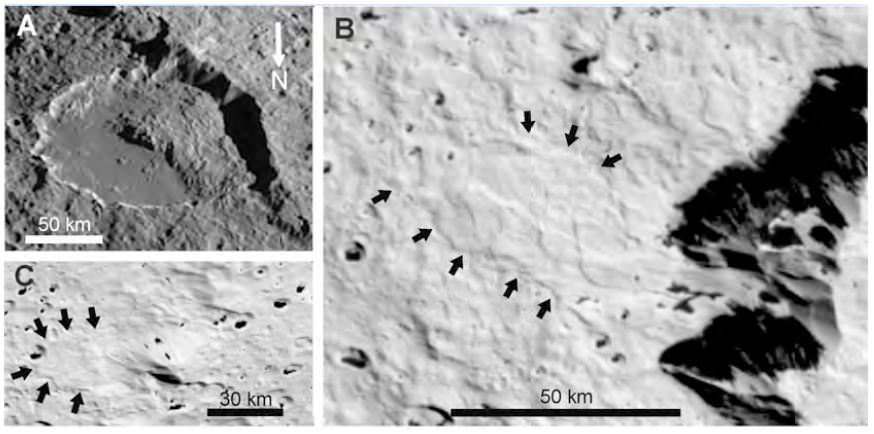

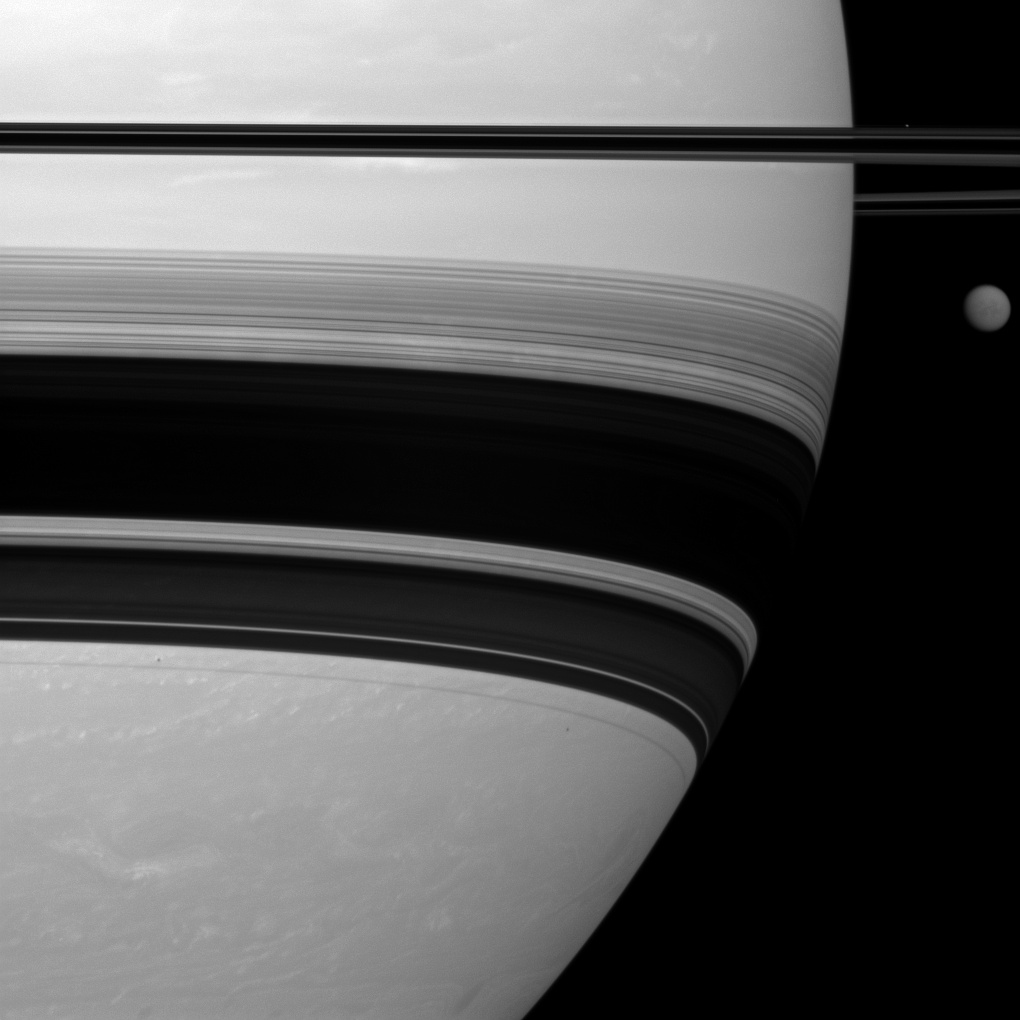

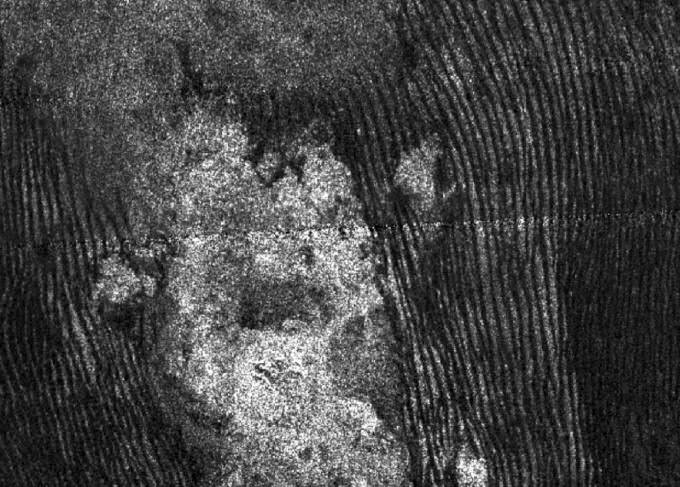

On Iapetus there is obviously no water or atmosphere to create conducive conditions for avalanches. But McKinnon and his team have identified over two dozen avalanche events as seen in images from the Cassini spacecraft.

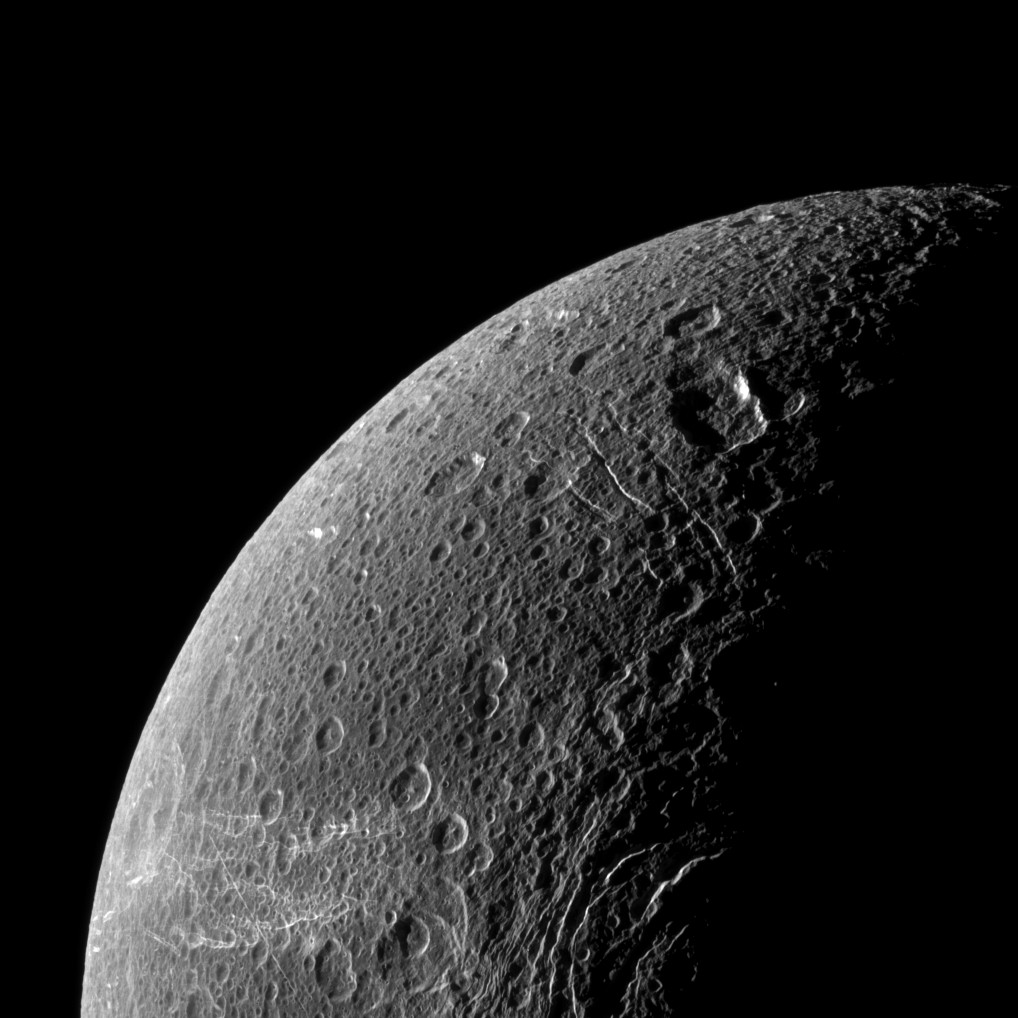

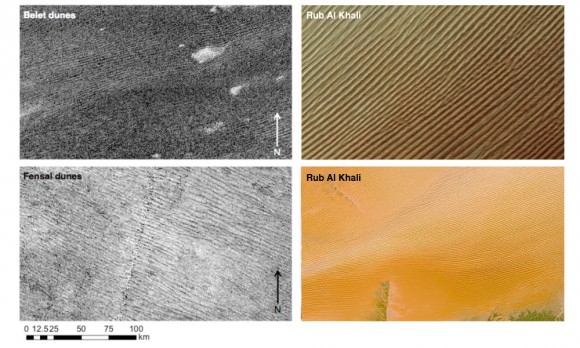

Many of the landslides are seen from crater and basin walls and steep scarps. McKinnon and his team have found two types of avalanches: ‘blocky’ with rough-looking debris and smoother lobate landslides. They also see evidence that over time, multiple avalanches have likely occurred in the same location, so Iapetus must have a long history of mass wasting and landslides.

So, what allows for the huge avalanches on Iapetus? McKinnon said ice provides the best answer to that question. The low density of Iapetus indicates that it is mostly composed of ice, with only about 20% of rocky materials.

“There seems to be a necessity for a fluidization or liquid mechanism,” McKinnon said. “If ice is warmed just enough it will become slippery,” reducing the friction and cohesiveness of the crater or basin wall.

What they are seeing, especially in the lobate landslides, is consistent with ‘rheological’ flow similar to molten lava or fluid mudslides.

So, ice rubble within the rocky faces of crater and basin walls are heated just enough – either by flash heating or friction — that the surfaces become slippery. “The energetics are favorable for this mechanism on Iapetus,” McKinnon said.

Iapetus has a very slow rotation, longer than 79 days, and such a slow rotation means that the daily temperature cycle is very long — so long that the dark material can absorb heat from the Sun and warm up. Of course the dark part of Iapetus absorbs more heat than the bright icy material; therefore, McKinnon said, this is all fairly enigmatic.

Plus, saying that it “warms up” on Iapetus is a bit of an overstatement. Temperatures on the dark region’s surface are estimated to reach 130 K (-143 °C; -226 °F) at the equator and temperatures in the brighter area only reach about 100 K (-173 °C; -280 °F).

Whatever the mechanisms, the long-runout landslides on Iapetus are fairly unique when it comes to icy planetary bodies. McKinnon referenced that just two mass movements of modest scale have been detected on Callisto, and there is limited evidence of similar events on Phoebe.

These ice avalanches certainly deserve more investigation on a moon which McKinnon described as having “singularly spectacular topography,” and additional research and a more detailed paper are forthcoming.

Read the LPSC abstract: Massive Ice Avalanches on Iapetus, and the Mechanism of Friction Reduction in Long-Runout Landslides