[/caption]

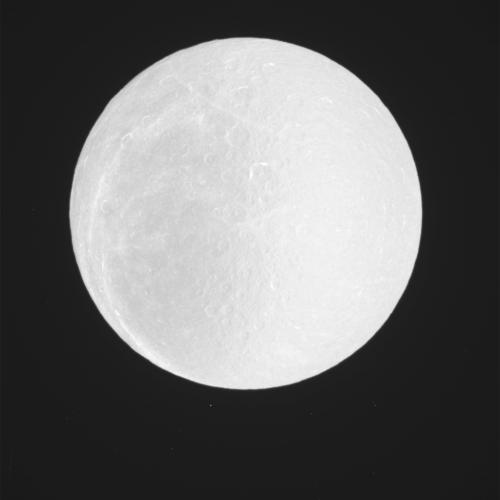

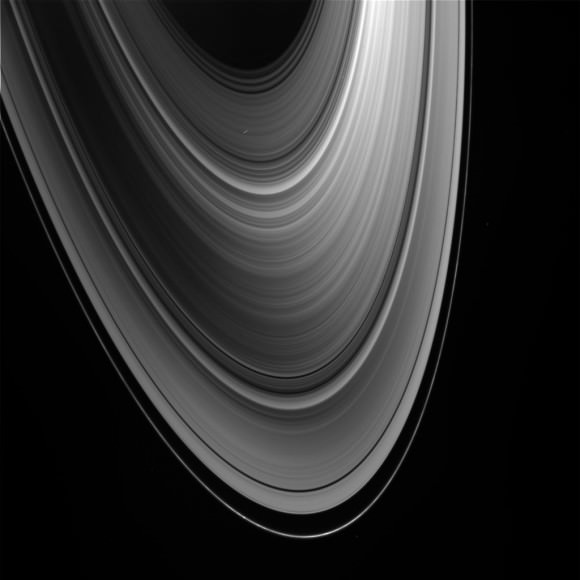

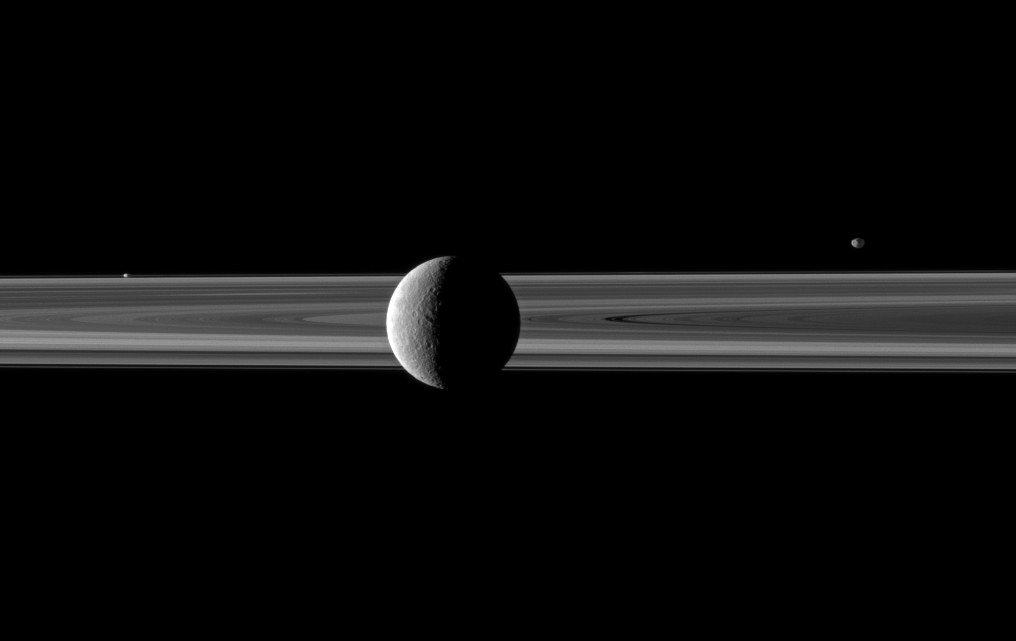

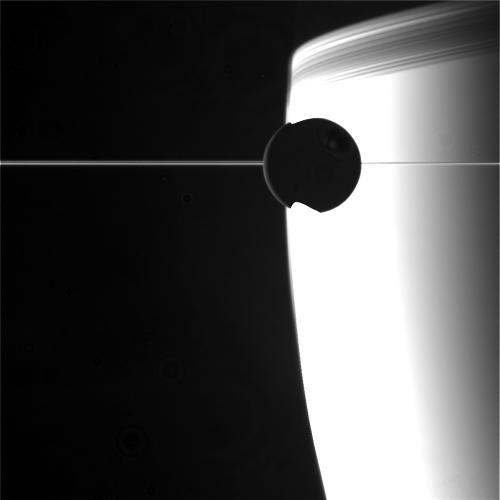

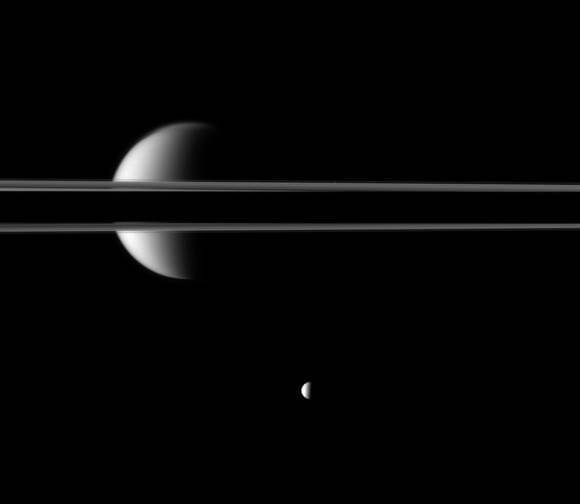

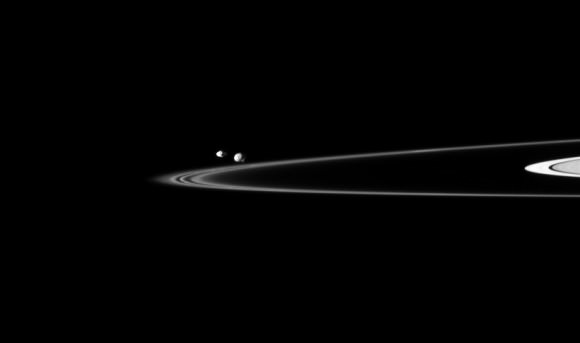

Back in 2005, a suite of six instruments on the Cassini spacecraft detected what was thought to be an extensive debris disk around Saturn’s moon Rhea, and while there was no visible evidence, researchers thought that perhaps there was a diffuse ring around the moon. This would have been the first ring ever found around a moon. New observations, however, have nixed the idea of a ring, but there’s still something around Rhea that is causing a strange, symmetrical structure in the charged-particle environment around Saturn’s second-largest moon.

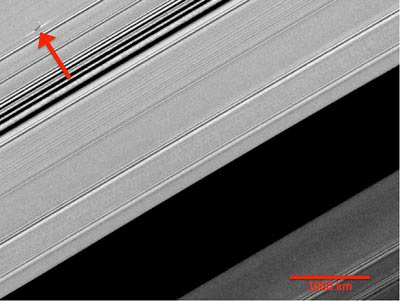

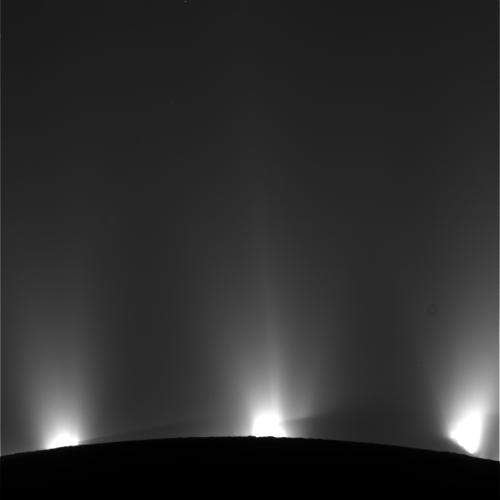

Researchers announced their findings in 2008 that there was a sharp, symmetrical drop in electrons detected around Rhea. This moon is about 1,500 kilometers (950 miles) in diameter, and scientists began searching for what could have caused the drop. If there were a debris disk around Rhea, it would have had to measure several thousand miles from end to end, and would probably be made of particles that would range from the size of small pebbles to boulders.

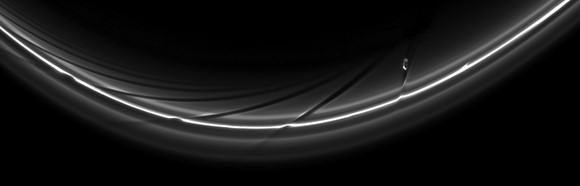

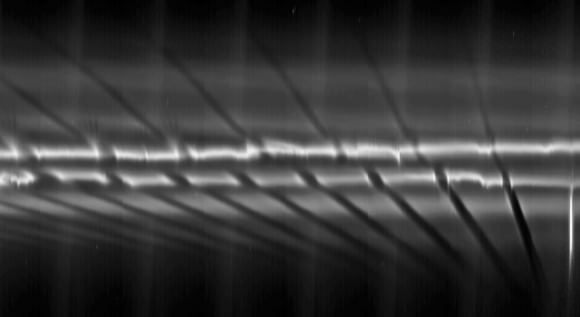

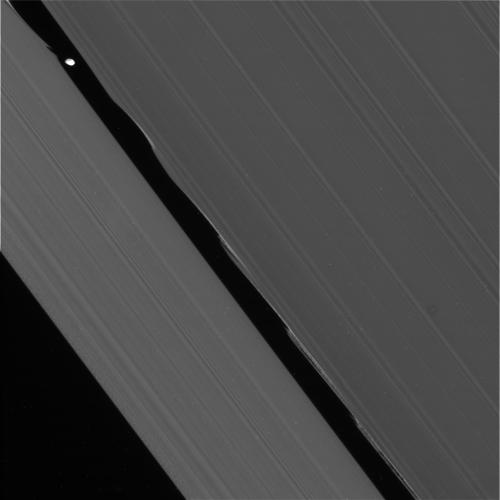

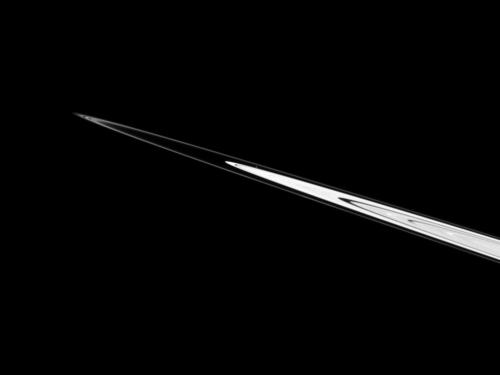

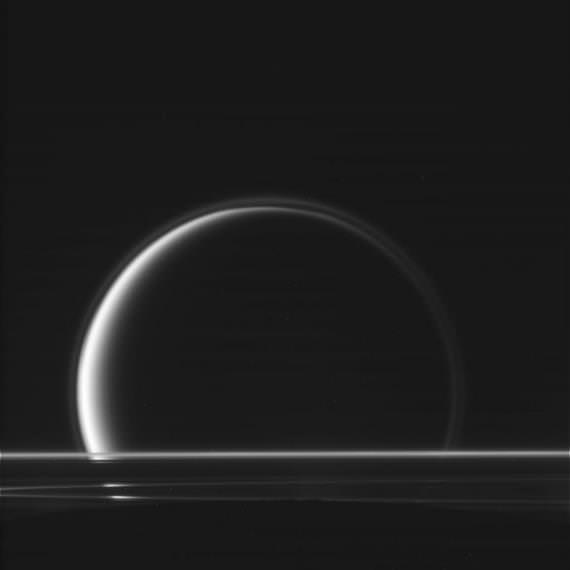

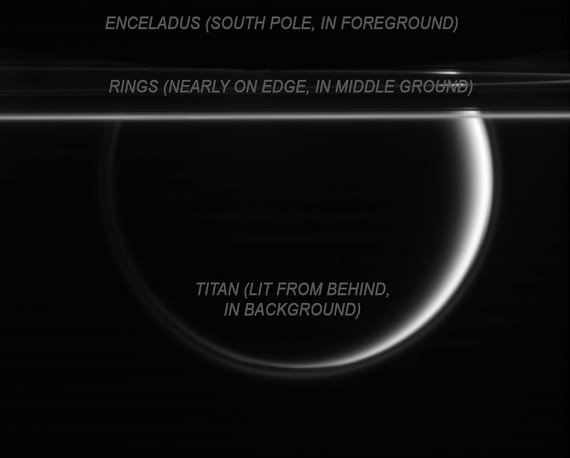

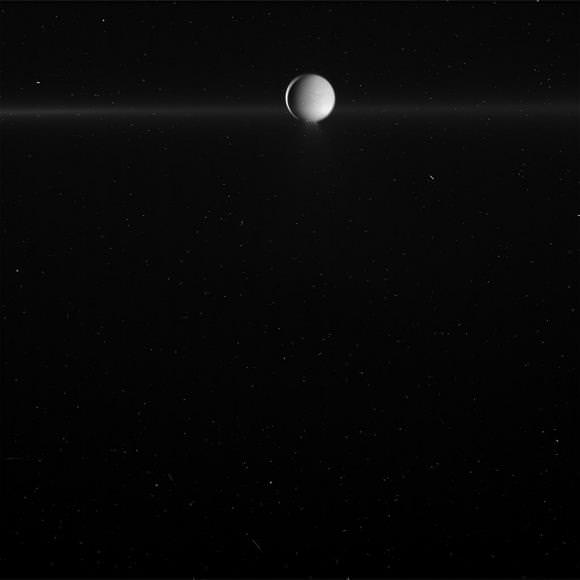

Testing the hypothesis, Cassini flew by the moon several times and took 65 images between 2008 and 2009, flying at what would be edge-on to the rings, where the greatest amount of material would be within its line of sight.

Using light angles to their advantage — and if the ring was there – the scientists should have been able to detect micron-sized particles up to boulder size objects.

But they saw nothing.

“There are very strong and interesting and unexplained electromagnetic effects going on around Rhea,” said Matthew Tiscareno from Cornell University, who led the imaging campaign. “But we’re making a pretty strong case that it’s not because of solid material orbiting the moon….For the amount of dust that you need to account for [the earlier] observations, if it were there, we would have seen it.”

While the ring hypothesis has been disproved, there’s still a mystery about the cause of the symmetrical structure in the charged-particles around the moon.

But the Cassini spacecraft and team are up for the challenge.

Source: Cornell University