Physicists working at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have announced the discovery of what they called a “Higgs-like boson” — a particle that resembles the long sought-after Higgs.

“We have reached a milestone in our understanding of nature,” CERN director general Rolf Heuer told scientists and media at a conference near Geneva on July 4, 2012. “The discovery of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson opens the way to more detailed studies, requiring larger statistics, which will pin down the new particle’s properties, and is likely to shed light on other mysteries of our universe.”

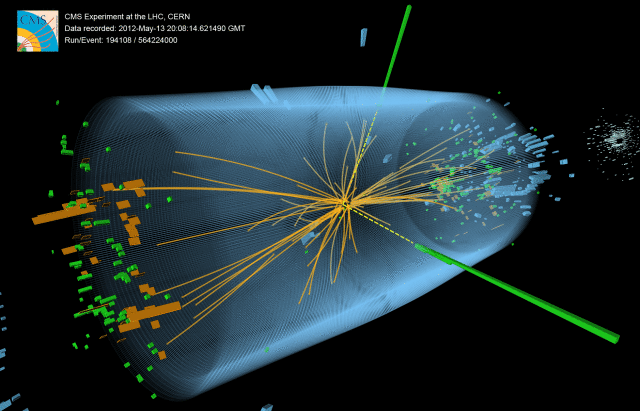

Two experiments, ATLAS and CMS, presented their preliminary results, and observed a new particle in the mass region around 125-126 GeV, the expected mass range for the Higgs Boson. The results are based on data collected in 2011 and 2012, with the 2012 data still under analysis. The official results will be published later this month and CERN said a more complete picture of today’s observations will emerge later this year after the LHC provides the experiments with more data.

“We observe in our data clear signs of a new particle, at the level of 5 sigma, in the mass region around 126 GeV. The outstanding performance of the LHC and ATLAS and the huge efforts of many people have brought us to this exciting stage,” said ATLAS experiment spokesperson Fabiola Gianotti, “but a little more time is needed to prepare these results for publication.”

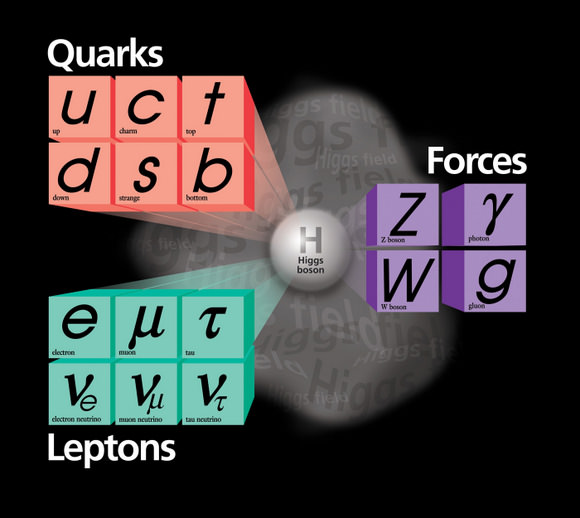

The discovery of the Higgs is big, in that it is the last undiscovered piece of the Standard Model that describes the fundamental make-up of the universe.

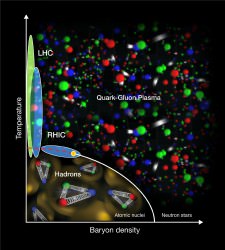

Scientists believe that the Higgs boson, named for Scottish physicist Peter Higgs, who first theorized its existence in 1964, is responsible for particle mass, the amount of matter in a particle. According to the theory, a particle acquires mass through its interaction with the Higgs field, which is believed to pervade all of space and has been compared to molasses that sticks to any particle rolling through it.

And so, in theory, the Higgs would be responsible for how particles come together to form matter, and without it, the universe would have remained a formless miss-mash of particles shooting around at the speed of light.

“It’s hard not to get excited by these results,” said CERN Research Director Sergio Bertolucci. “We stated last year that in 2012 we would either find a new Higgs-like particle or exclude the existence of the Standard Model Higgs. With all the necessary caution, it looks to me that we are at a branching point: the observation of this new particle indicates the path for the future towards a more detailed understanding of what we’re seeing in the data.”

A CERN press release says that the next step will be to determine the precise nature of the particle and its significance for our understanding of the universe.

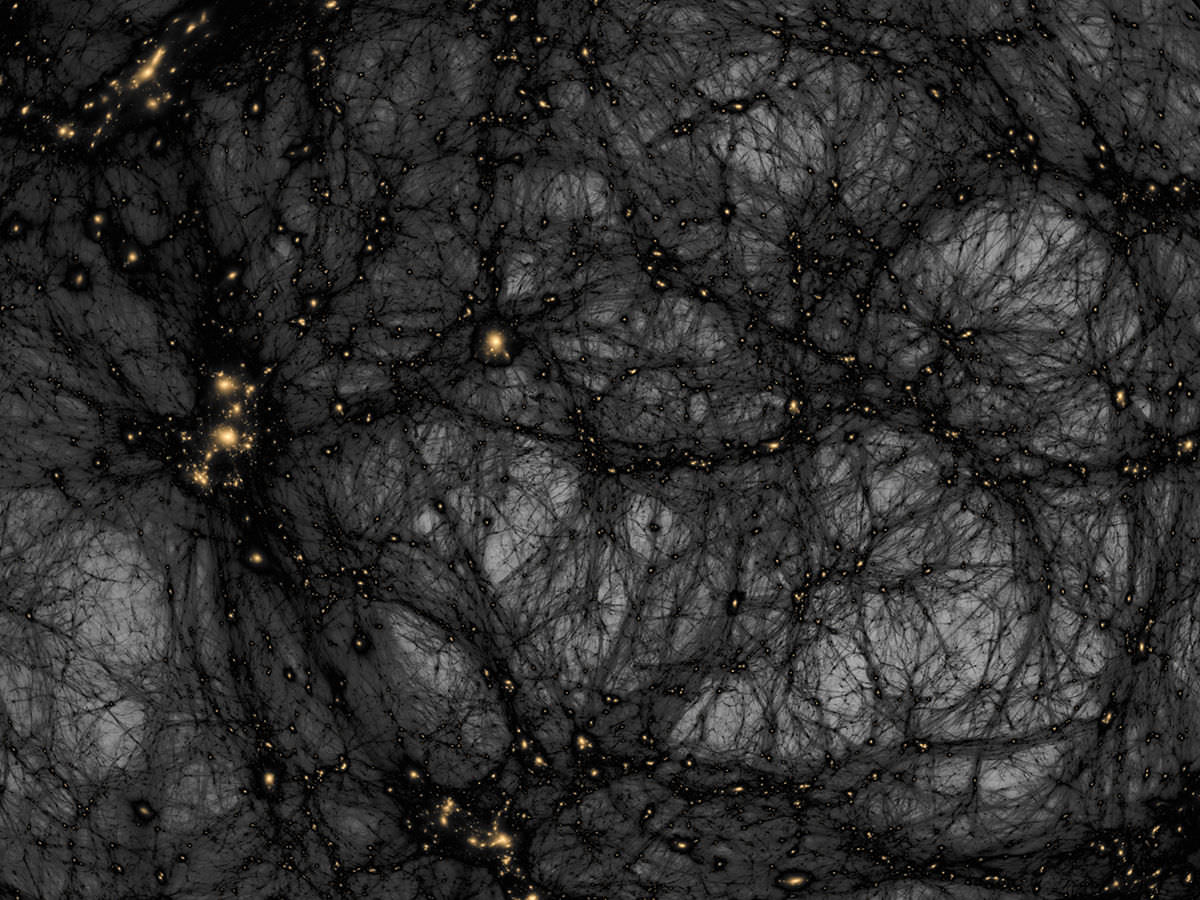

Are its properties as expected for the long-sought Higgs boson, the final missing ingredient in the Standard Model of particle physics? Or is it something more exotic? The Standard Model describes the fundamental particles from which we, and every visible thing in the universe, are made, and the forces acting between them. All the matter that we can see, however, appears to be no more than about 4% of the total. A more exotic version of the Higgs particle could be a bridge to understanding the 96% of the universe that remains obscure. – CERN press release

“We have reached a milestone in our understanding of nature,” said CERN Director General Rolf Heuer. “The discovery of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson opens the way to more detailed studies, requiring larger statistics, which will pin down the new particle’s properties, and is likely to shed light on other mysteries of our universe.”

Positive identification of the new particle’s characteristics will take more time and more experiments. But the scientists feel that whatever form the Higgs particle takes, our knowledge of the fundamental structure of matter is about to take a major step forward.

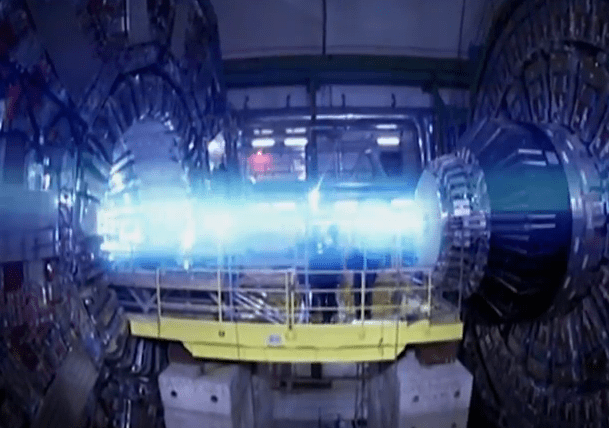

Lead image caption: Event recorded with the CMS detector in 2012 at a proton-proton centre of mass energy of 8 TeV. The event shows characteristics expected from the decay of the SM Higgs boson to a pair of photons (dashed yellow lines and green towers). The event could also be due to known standard model background processes. Credit: CERN

Source: CERN