This week, the 229th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) kicked off in Grapevine, Texas. Between Monday and Friday (January 3rd to January 7th), attendees will be hearing presentations by researchers and scientists from several different fields as they share the latest discoveries in astronomy and Earth science.

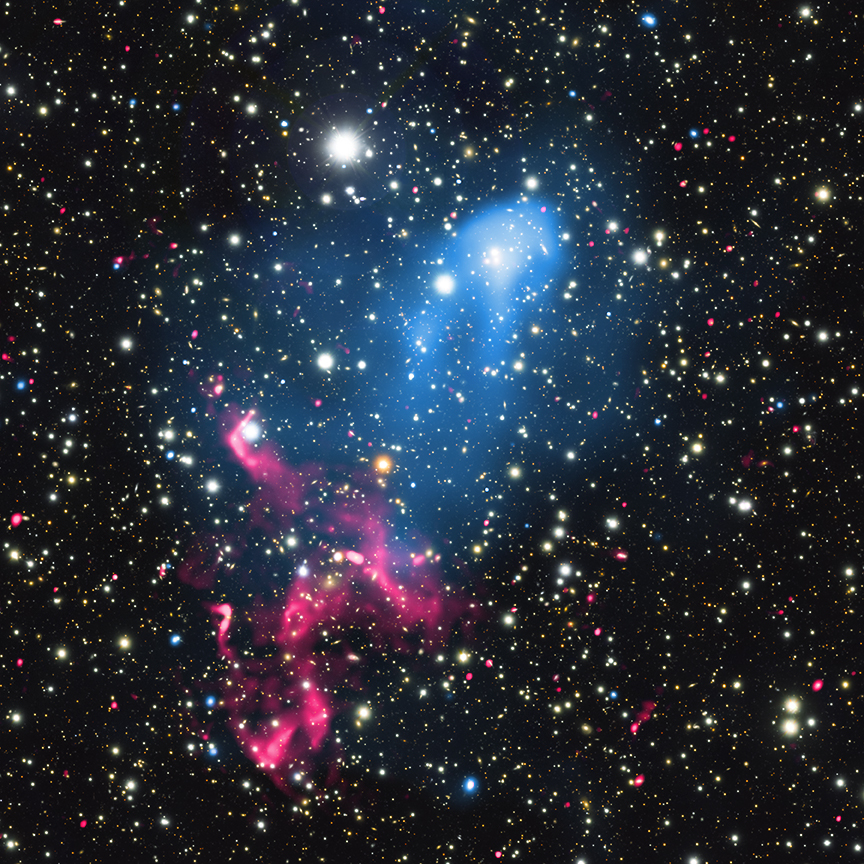

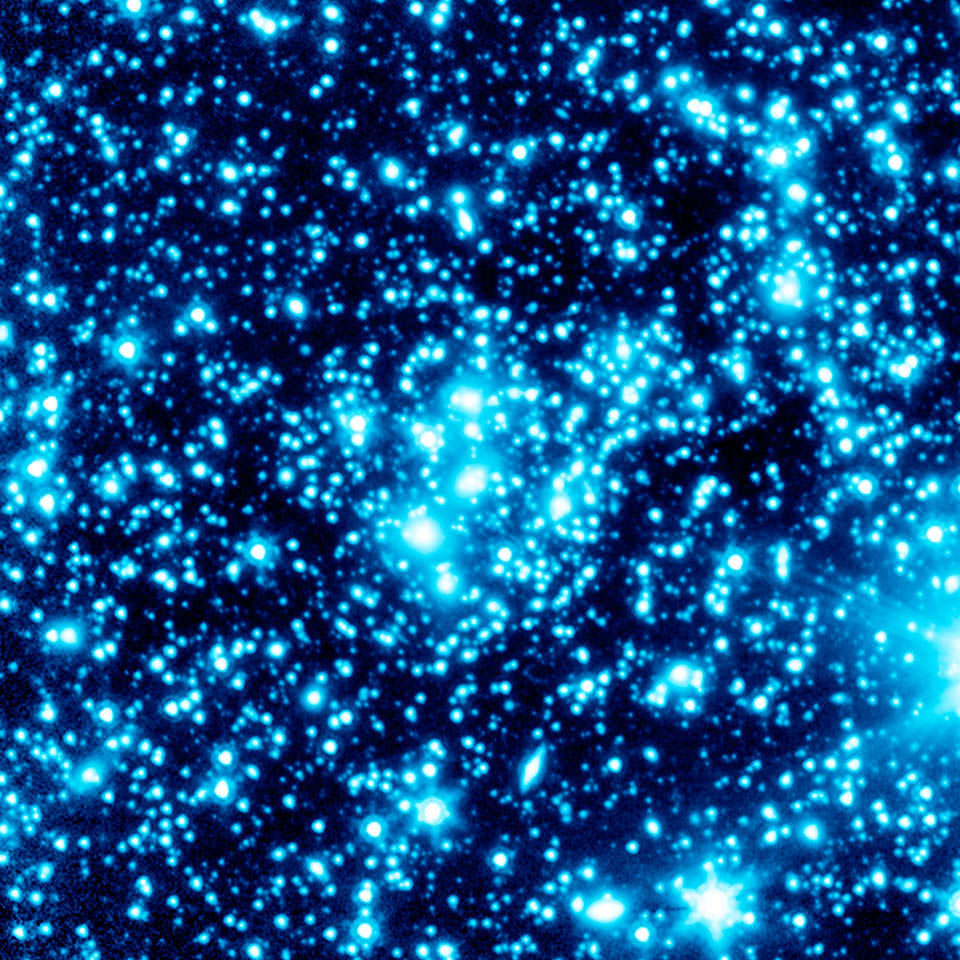

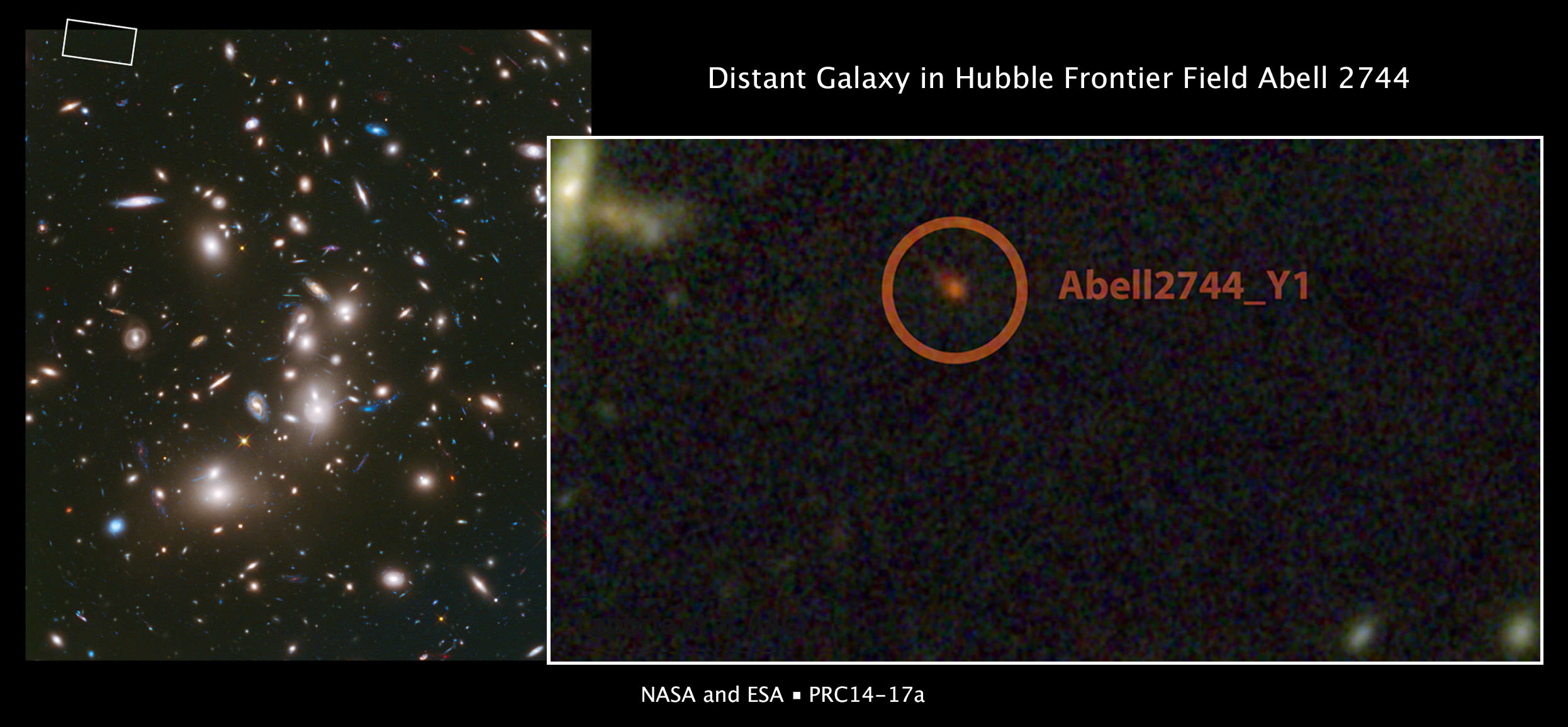

One of the highlights so far this week was a presentation from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which took place on the morning of Wednesday, January 5th. In the course of the presentation, an international research team showed some stunning images of two of the most powerful cosmic forces seen together for the first time – a supermassive black hole and two massive galaxy clusters colliding.

The galaxy clusters are known as Abell 3411 and Abell 3412, which are located about two billion light years from Earth. Both of these clusters are quite massive, each possessing the equivalent of about a quadrillion times the mass of our Sun. Needless to say, the collision of these objects produced quite the shockwave, which included the release of hot gas and energetic particles.

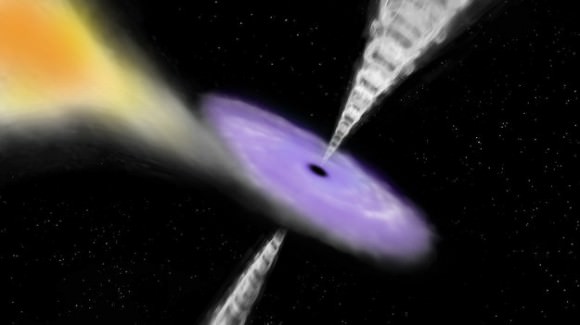

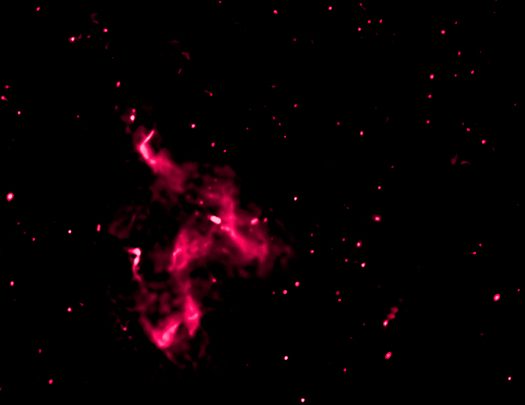

This was made all the more impressive thanks to the presence of a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at the center of one of the galaxy clusters. As the team described in their paper – titled “The Case for Electron Re-Acceleration at Galaxy Cluster Shocks” – the galactic collision produced a nebulous outburst of x-rays (shown above), which were produced when hot clouds of gas from one cluster plowed through the hot gas clouds of the other.

Meanwhile, the inflowing gas was accelerated outward into a jet-like stream, thanks to the powerful electromagnetic fields of the SMBH. These particles were accelerated even further when they got swept up by the shock waves produced by the collision of the galactic clusters and their massive gas clouds. These streams were detected thanks to the burst of radio waves they released as a result.

By seeing these two major events happening at the same time in the same place, the research team effectively witnessed a cosmic “double whammy”. As Felipe Andrade-Santos of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), and co-author of the paper, described it in a Chandra press release:

“It’s almost like launching a rocket into low-Earth orbit and then getting shot out of the Solar System by a second rocket blast. These particles are among the most energetic particles observed in the Universe, thanks to the double injection of energy.”

Relying on data obtained from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) in India, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, the Keck Observatory, and Japan’s Subaru Telescope, the team was able to capture this event in the optical, x-ray, and radio wave wavelengths. This not only led to some stunning images, but shed some light on a long-standing mystery in galaxy research.

In the past, astronomers have detected radio emissions coming from Abell 3411 and Abell 3412 using the GMRT. But the origins of these emissions, which reached for millions of light years, was the subject of speculation and debate. Relying on the data they obtained, the research team was able to determine that they are the result of energetic particles (produced by the clouds of hot gas colliding) being further accelerated by galactic shock waves.

Or as co-author William Dawson, of the Lawrence Livermore National Lab in Livermore, California, put it:

“This result shows that a remarkable combination of powerful events generate these particle acceleration factories, which are the largest and most powerful in the Universe. It is a bit poetic that it took a combination of the world’s biggest observatories to understand this.”

Many interesting finds have been shared since the 229th Meeting of the AAS began – like the hunt for the source of a Fast Radio Burst – and many more are expected before it wraps up at the end of the week. These will include the latest results from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), and new and exciting research on black holes, exoplanets, and other astronomical phenomena.

And be sure to check out this podcast from Chandra as well, which talks about the collision between Abell 3411 and 3412 and the cosmic forces it unleashed.

Further Reading: Chandra X-ray Observatory