[/caption]

From a NASA press release:

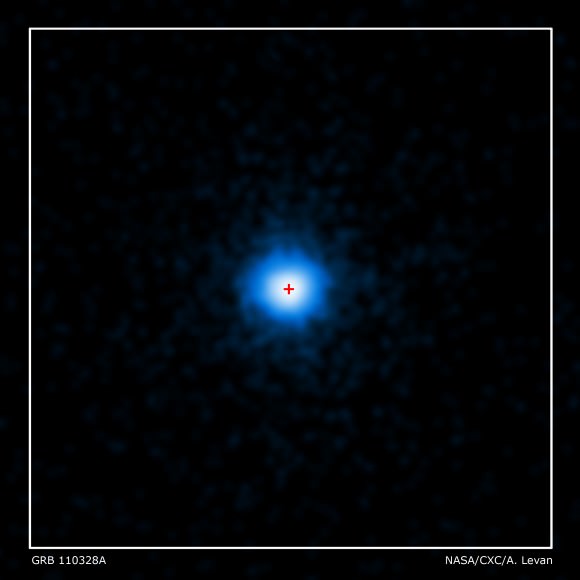

A new study from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory tells scientists how often the biggest black holes have been active over the last few billion years. This discovery clarifies how supermassive black holes grow and could have implications for how the giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way will behave in the future.

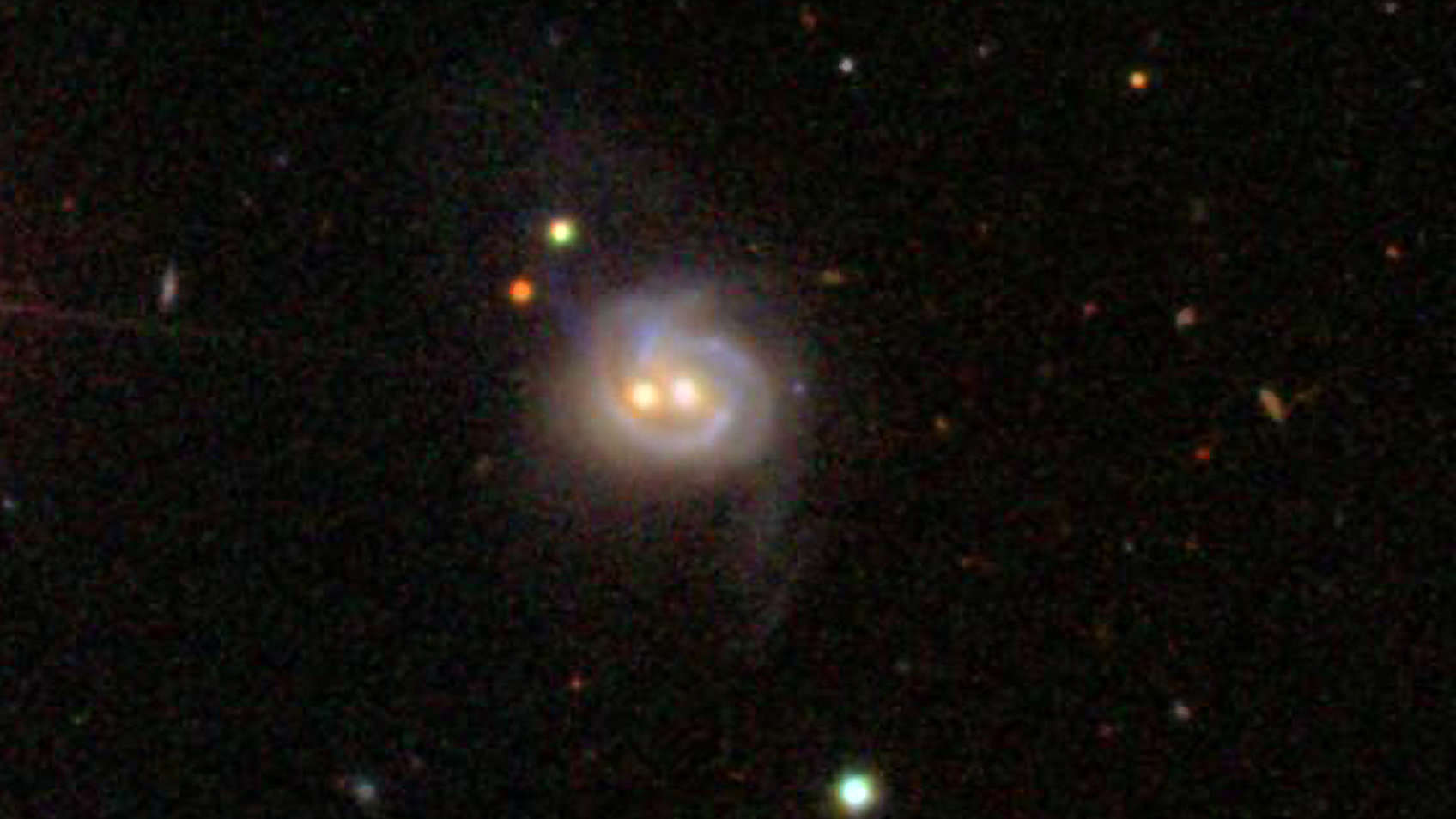

Most galaxies, including our own, are thought to contain supermassive black holes at their centers, with masses ranging from millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. For reasons not entirely understood, astronomers have found that these black holes exhibit a wide variety of activity levels: from dormant to just lethargic to practically hyper.

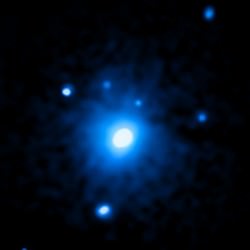

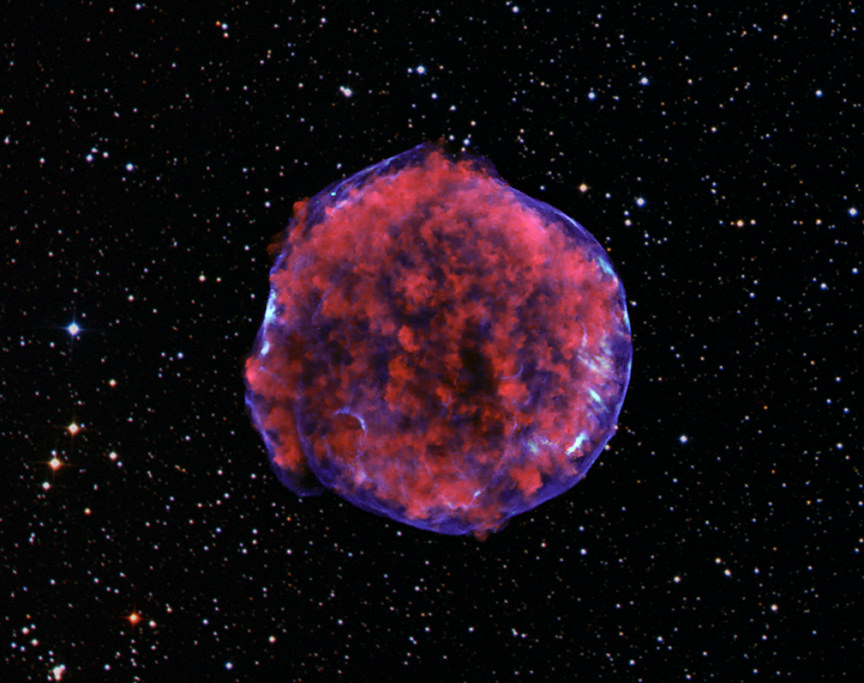

The most lively supermassive black holes produce what are called “active galactic nuclei,” or AGN, by pulling in large quantities of gas. This gas is heated as it falls in and glows brightly in X-ray light.

“We’ve found that only about one percent of galaxies with masses similar to the Milky Way contain supermassive black holes in their most active phase,” said Daryl Haggard of the University of Washington in Seattle, WA, and Northwestern University in Evanston, IL, who led the study. “Trying to figure out how many of these black holes are active at any time is important for understanding how black holes grow within galaxies and how this growth is affected by their environment.”

This study involves a survey called the Chandra Multiwavelength Project, or ChaMP, which covers 30 square degrees on the sky, the largest sky area of any Chandra survey to date. Combining Chandra’s X-ray images with optical images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, about 100,000 galaxies were analyzed. Out of those, about 1,600 were X-ray bright, signaling possible AGN activity.

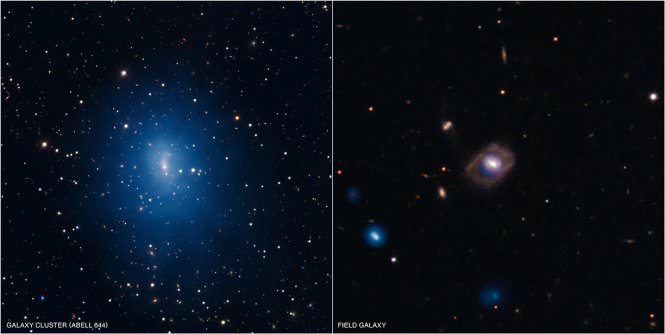

Only galaxies out to 1.6 billion light years from Earth could be meaningfully compared to the Milky Way, although galaxies as far away as 6.3 billion light years were also studied. Primarily isolated or “field” galaxies were included, not galaxies in clusters or groups.

“This is the first direct determination of the fraction of field galaxies in the local Universe that contain active supermassive black holes,” said co-author Paul Green of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, MA. “We want to know how often these giant black holes flare up, since that’s when they go through a major growth spurt.”

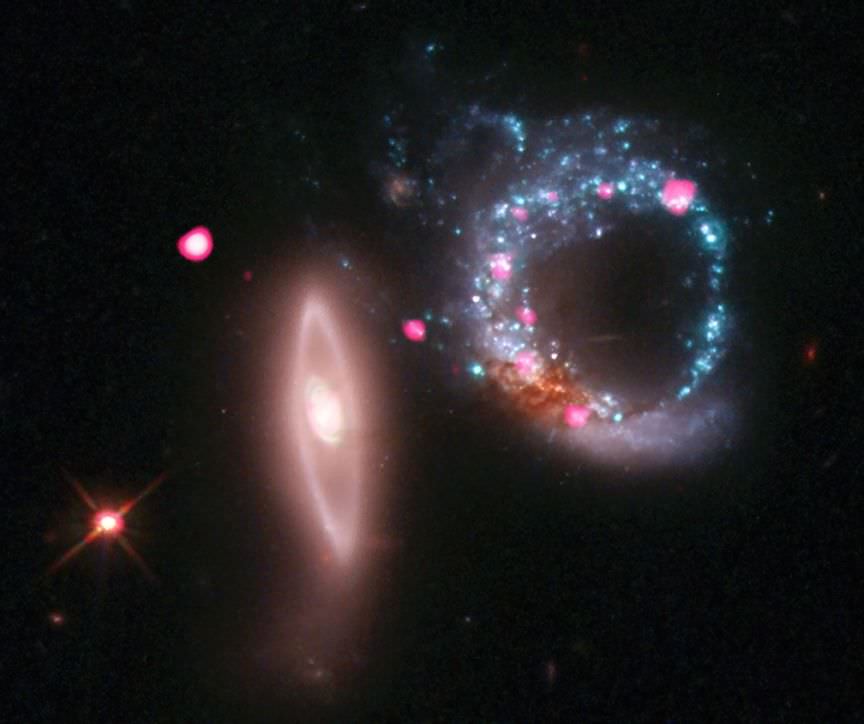

A key goal of astronomers is to understand how AGN activity has affected the growth of galaxies. A striking correlation between the mass of the giant black holes and the mass of the central regions of their host galaxy suggests that the growth of supermassive black holes and their host galaxies are strongly linked. Determining the AGN fraction in the local Universe is crucial for helping to model this parallel growth.

One result from this study is that the fraction of galaxies containing AGN depends on the mass of the galaxy. The most massive galaxies are the most likely to host AGN, whereas galaxies that are only about a tenth as massive as the Milky Way have about a ten times smaller chance of containing an AGN.

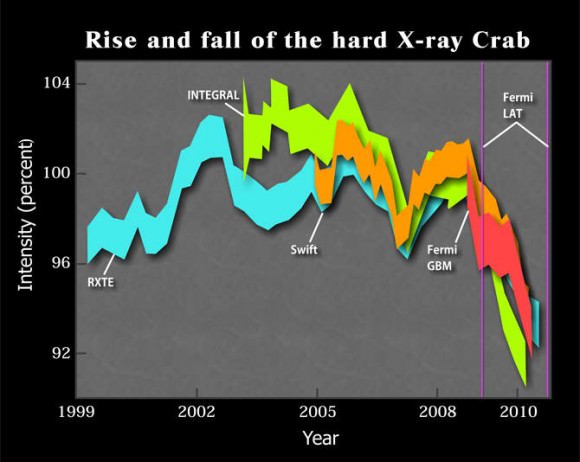

Another result is that a gradual decrease in the AGN fraction is seen with cosmic time since the Big Bang, confirming work done by others. This implies that either the fuel supply or the fueling mechanism for the black holes is changing with time.

The study also has important implications for understanding how the neighborhoods of galaxies affects the growth of their black holes, because the AGN fraction for field galaxies was found to be indistinguishable from that for galaxies in dense clusters.

“It seems that really active black holes are rare but not antisocial,” said Haggard. “This has been a surprise to some, but might provide important clues about how the environment affects black hole growth.”

It is possible that the AGN fraction has been evolving with cosmic time in both clusters and in the field, but at different rates. If the AGN fraction in clusters started out higher than for field galaxies — as some results have hinted — but then decreased more rapidly, at some point the cluster fraction would be about equal to the field fraction. This may explain what is being seen in the local Universe.

The Milky Way contains a supermassive black hole known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*, for short). Even though astronomers have witnessed some activity from Sgr A* using Chandra and other telescopes over the years, it has been at a very low level. If the Milky Way follows the trends seen in the ChaMP survey, Sgr A* should be about a billion times brighter in X-rays for roughly 1% of the remaining lifetime of the Sun. Such activity is likely to have been much more common in the distant past.

If Sgr A* did become an AGN it wouldn’t be a threat to life here on Earth, but it would give a spectacular show at X-ray and radio wavelengths. However, any planets that are much closer to the center of the Galaxy, or directly in the line of fire, would receive large and potentially damaging amounts of radiation.

These results were published in the November 10th issue of the Astrophysical Journal. Other co-authors on the paper were Scott Anderson of the University of Washington, Anca Constantin from James Madison University, Tom Aldcroft and Dong-Woo Kim from Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Wayne Barkhouse from the University of North Dakota.