[/caption]

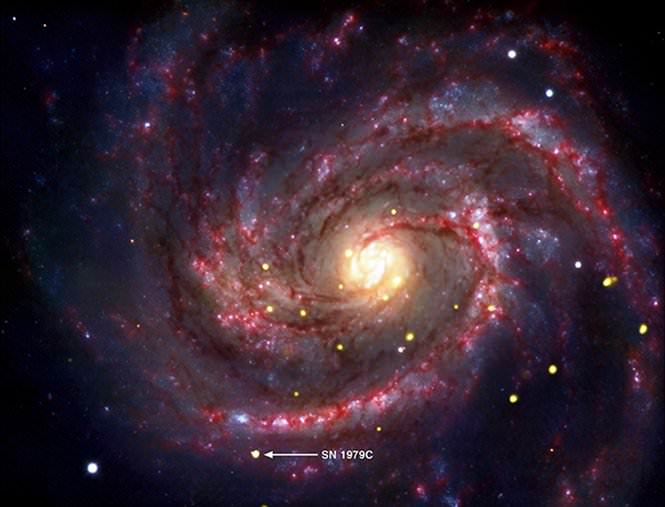

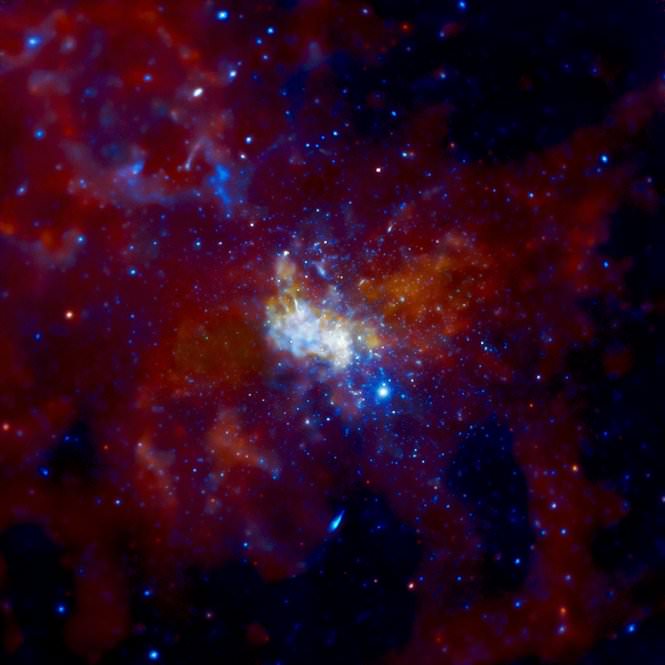

Back in 1979, amateur astronomer Gus Johnson discovered a supernova about 50 million light years away from Earth, when a star about 20 times more massive than our Sun collapsed. Since then, astronomers have been keeping an eye on SN 1979C, located in M 100 in the Virgo cluster. With observations from the Chandra telescope, the X-ray emissions from the object have led astronomers to believe the supernova remnant has become a black hole. If so, it would be the youngest black hole known to exist in our nearby cosmic neighborhood and would provide astronomers the unprecedented opportunity to watch this type of object develop from infancy.

“If our interpretation is correct, this is the nearest example where the birth of a black hole has been observed,” said astronomer Daniel Patnaude during a NASA press briefing on Monday. Patnaude is from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and is the lead author of a new paper.

SN 1970C belongs to a type of supernova explosions called Type II linear, or core collapse supernovae, which make up about 6% of known stellar explosions. While many new black holes in the distant universe previously have been detected in the form of gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), SN 1979C is different because it is much closer and core collapse supernovae are unlikely to be associated with a GRB. Theories say that most black holes should form when the core of a star collapses and a gamma-ray burst is not produced, but this may be the first time that this method of making a black hole has been observed.

There has been a debate on what size star will create a black hole what size will create a neutron star. The 20 solar mass size is right on the boundary between the two, so astronomers are not completely sure this is a black hole or a neutron star. But since the X-ray emissions from this object have been steady over the past 31 years, astronomers believe this is a black hole, since as a neutron star cools, the X-ray emissions fade.

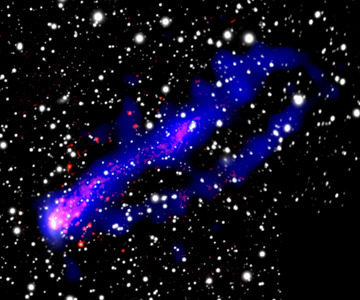

This animation shows how a black hole may have formed in SN 1979C. The collapse of a massive star is shown, after it has exhausted its fuel. A flash of light from a shock breaking through the surface of the star is then shown, followed by a powerful supernova explosion. The view then zooms into the center of the explosion: Credits: NASA/CXC/A.Hobart

However, as a caveat, co-author Avi Loeb said, it really takes about a lot longer than 31 years to see big changes, but he said the fact that the illumination has been steady gives evidence for a black hole.

Although the evidence does point to a newly formed black hole, there are a few other possibilities of what it could be. Some have suggested the object could be a magnetar or a blast wave, but the evidence is showing those two options are not very probable.

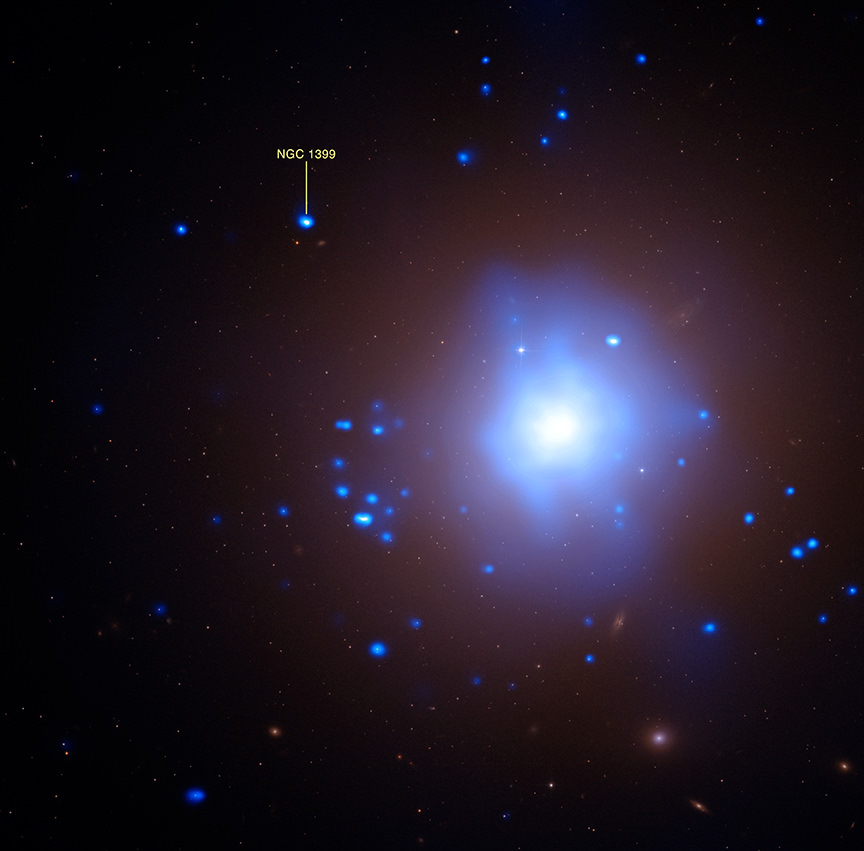

Another intriguing possibility is that a young, rapidly spinning neutron star with a powerful wind of high energy particles could be responsible for the X-ray emission. This would make the object in SN 1979C the youngest and brightest example of such a “pulsar wind nebula” and the youngest known neutron star. The Crab pulsar, the best-known example of a bright pulsar wind nebula, is about 950 years old.

“I’m excited about this discovery regardless if it turns out to be black hole or a pulsar wind nebula,” said astrophysicst Alex Fillipenko, who participated in the briefing. “A pulsar wind nebula would be interesting because it would be the youngest known in that category.”

“What is really exciting is that for the first time we know the exact birth date of this object,” said Kim Weaver, an astrophycisict from Goddard Space Flight Center, “We know it is very young and we want to watch how the system evolves and changes, as it grows into a child and becomes a teenager. More importantly, we’ll be able to understand the physics. This is a story of science in action.”

The age of the possible black hole is, of course, based on our vantage point. Since the galaxy is 50 million light years away, the supernova occurred 50 million years ago. But for us, the explosion took place just 31 years ago.

Read the team’s paper: Evidence for a Black Hole Remnant in the Type IIL Supernova 1979C

Authors: D.J. Patnaude, A. Loeb, C. Jones.

Source: NASA TV briefing, NASA