[/caption]

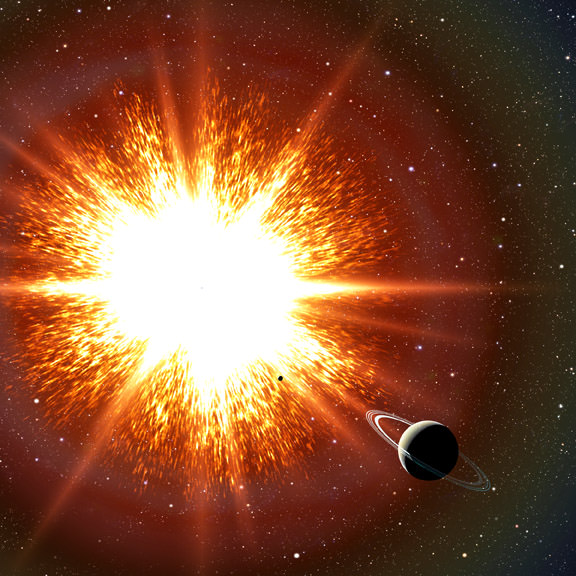

According to new research, the only thing that may be keeping elderly stars from exploding is their rapid spin. In a galaxy filled with old stars, this means we could literally be sitting on a nearby “time bomb”. Or is this just another scare tactic?

“We haven’t found one of these ‘time bomb’ stars yet in the Milky Way, but this research suggests that we’ve been looking for the wrong signs. Our work points to a new way of searching for supernova precursors,” said astrophysicist Rosanne Di Stefano of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

In light of the two recently discovered supernova events in Messier 51 and Messier 101, it isn’t hard to imagine the Milky Way having more than one candidate for a Type Ia supernova. This is precisely the type of stellar explosion Di Stefano and her colleagues are looking for… and it happens when a white dwarf star goes critical. It has reached Chandrasekhar mass. Add any more weight and it blows itself apart. How does this occur? Some astronomers believe Type Ia supernova are sparked by accretion from a binary companion – or a collision of two similar dwarf stars. However, there hasn’t been much – if any – evidence to support either theory. This has left scientists to look for new answers to old questions. Di Stefano and her colleagues suggest that white dwarf spin might just be what we’re looking for.

“A spin-up/spin-down process would introduce a long delay between the time of accretion and the explosion. As a white dwarf gains mass, it also gains angular momentum, which speeds up its spin. If the white dwarf rotates fast enough, its spin can help support it, allowing it to cross the 1.4-solar-mass barrier and become a super-Chandrasekhar-mass star. Once accretion stops, the white dwarf will gradually slow down. Eventually, the spin isn’t enough to counteract gravity, leading to a Type Ia supernova.” explains Di Stefano. “Our work is new because we show that spin-up and spin-down of the white dwarf have important consequences. Astronomers therefore must take angular momentum of accreting white dwarfs seriously, even though it’s very difficult science.”

Sure. It might take a billion years for the spin down process to happen – but what’s a billion years in cosmic time? In this scenario, it’s enough to allow accretion to have completely stopped and a companion star to age to a white dwarf. In the Milky Way there’s an estimated three Type Ia supernovae every thousand years. If figures are right, a typical super-Chandrasekhar-mass white dwarf takes millions of years to spin down and explode. This means there could be dozens of these “time bomb” systems within a few thousand light-years of Earth. While we’re not able to ascertain their locations now, upcoming wide-field surveys taken with instruments like Pan-STARRS and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope might give us a clue to their location.

“We don’t know of any super-Chandrasekhar-mass white dwarfs in the Milky Way yet, but we’re looking forward to hunting them out,” said co-author Rasmus Voss of Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

And the rest of us hope you don’t find them…

Original Story Source: Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics News. For Further Reading: Spin-Up/Spin-Down models for Type Ia Supernovae.