Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at that Great and most brightest of nebulae – the Orion Nebula!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

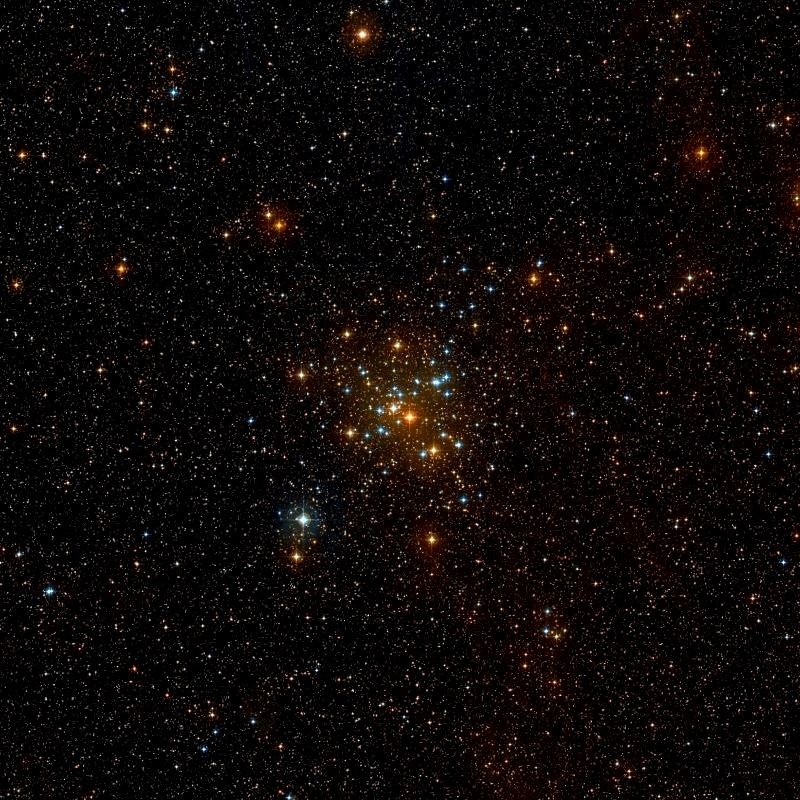

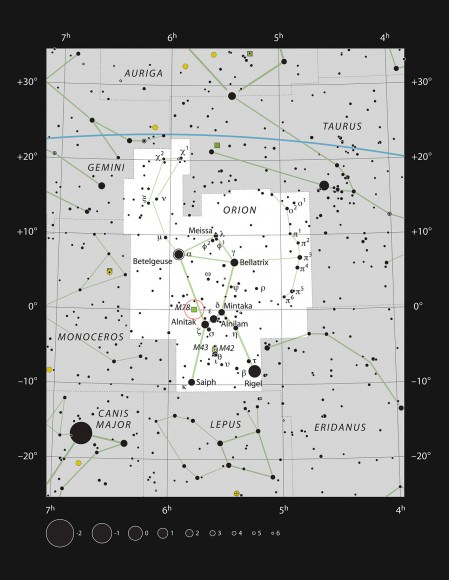

One of these objects is the Orion Nebula, a diffuse nebula situated just south of Orion’s Belt in the Orion constellation. Located between 1,324 and 1,364 light years distant, it is the closest massive star forming region to Earth. Little wonder then why it is the brightest nebula in the night sky and can be seen on a clear evening with the naked eye.

Description:

Known as “The Great Orion Nebula,” let’s learn what makes it glow. M42 is a great cloud of gas spanning more than 20,000 times the size of our own solar system and its light is mainly florescent. For most observers, it appears to have a slight greenish color – caused by oxygen being stripped of electrons by radiation from nearby stars.

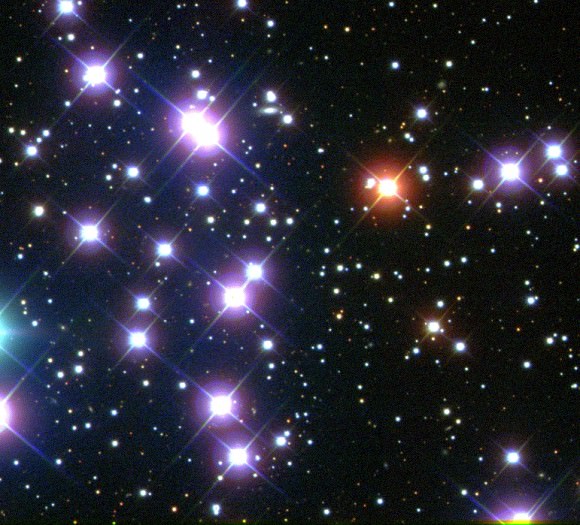

At the heart of this immense region is an area known as the “Trapezium” – its four brightest stars form perhaps the most celebrated multiple star system in the night sky. The Trapezium itself belongs to a faint cluster of stars now approaching main sequence and resides in an area of the nebula known as the “Huygenian Region” (named after 17th century astronomer and optician Christian Huygens who first observed it in detail).

Buried amidst the bright ribbons and curls of this cloud of predominately hydrogen gas are many star forming regions. Appearing like “knots,” these Herbig-Haro objects are thought to be stars in the earliest stages of condensation. Associated with these objects are a great number of faint red stars and erratically luminous variables – young stars, possibly of the T Tauri type.

There are also “flare stars,” whose rapid variations in brightness mean an ever changing view. “Orion may seem very peaceful on a cold winter night, but in reality it holds very massive, luminous stars that are destroying the dusty gas cloud from which they formed,” said Tom Megeath, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

While studying M42, you’ll note the apparent turbulence of the area – and with good reason. The “Great Nebula’s” many different regions move at varying speeds. The rate of expansion at the outer edges may be caused by radiation from the very youngest stars present. Said Massimo Roberto, an astronomer at the Space Science Telescope Institute in Baltimore:

“In this bowl of stars we see the entire formation history of Orion printed into the features of the nebula: arcs, blobs, pillars and rings of dust that resemble cigar smoke. Each one tells a story of stellar winds from young stars that impact the environment and the material ejected from other stars.”

Although M42 may have been luminous for as long as 23,000 years, it is possible that new stars are still forming, while others were ejected by gravitation – known as “runaway” stars. A tremendous X-ray source (2U0525-06) is quite near the Trapezium and hints at the possibility of a black hole present within M42. The Trapezium’s stellar winds also are responsible for the formation of stars inside the nebula – their shock waves compressing the medium and igniting starbirth.

“When you look closely, you see that the nebula is filled with hundreds of visible shock waves,” said Bob O’Dell, an astronomer from Vanderbilt University. O’Dell was fortunate enough to use Hubble to map Orion’s stellar winds and create a map of two of Orion’s three star-forming regions… Regions where the winds have been blowing continuously for nearly 1,500 years!

What else have we learned about the Great Orion nebula in recent years? Try the discovery of 13 drifting gas planets. These rare, “free-floating” objects were confirmed by Patrick Roche of the University of Oxford and Philip Lucas of the University of Hertfordshire just before the turn of the century. They were found with the Hubble Space Telescope while looking for faint stars and brown dwarfs. As he explained:

“The objects are likely to be large gas planets similar in size to Jupiter and consisting primarily of hydrogen and helium. From the measured brightness and the known distance to the Orion nebula, we knew they did not have enough material for any nuclear processing in their interiors.”

Chances are very good these planets may be failed stars – much like our own Jupiter. But these planets don’t orbit a star the same way our solar system’s planets orbit the Sun… they simply roam around. Dr. Roche said that the 13 objects “probably formed in a different way from the planets in our solar system” in that they were not made “out of the residue of material left over from the birth of the sun.”

Instead, they formed “like stars via the collapse of a cloud of cold gas,” explained Lucas. “But they possess most of the physical properties and structure of gas giant planets,” added Lucas.

History of Observation:

Messier 42 was possibly discovered 1610 by Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and was recorded by by Johann Baptist Cysatus, Jesuit astronomer, in 1611. For fans of the great Galileo, he was the first to mention the Trapezium cluster in 1617, but did not see the nebula. (However, do not despair! For it is my belief that he was simply using too much magnification and therefore could not see the extent of what he was looking at.)

The first known drawing of the Orion nebula was created by Giovanni Batista Hodierna, and after all of these documents were lost, the Orion nebula was once again credited to Christian Huygens 1656, documented by Edmund Halley in 1716. It then went on to Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan in his nebulae descriptions, to be added by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux to his list, expounded by Guillaume Legentil in his review.

At last, Charles Messier added the nebula to his catalog on March 4, 1769. As he wrote of the stunning objectL

“The drawing of the nebula in Orion, which I present at the Academy, has been traced with the greatest care which is possible for me. The nebula is represented there as I have seen it several times with an excellent achromatic refractor of three and a half feet focal length, with a triple lens, of 40 lignes [3.5 inches] aperture, and which magnifies 68 times. This telescope made in London by Dollond, belongs to M. President de Saron. I have examined that nebula with the greatest attention, in an entirely serene sky, as follows: February 25 & 26, 1773. Orion in the Meridian. March 19, between 8 & 9 o’clock in the evening. [March] 23, between 7 & 8 o’clock. The 25th & 26th of the same month, at the same time. These combined observations and the drawings brought together, have enabled me to represent with care and precision its shape and its appearances.

“This drawing will serve to recognize, in following times, if this nebula is subject to any changes. There may be already cause to presume this; for, if one compares this drawing with those given by MM. Huygens, Picard, Mairan and by le Gentil, one finds there such a change that one would have difficulty to figure out that this was the same. I will make these observations in the following with the same telescope and the same magnification. In the figure which I give, the circle represents the field of the telescope in its true aperture; it contains the Nebula and thirty Stars of different magnitudes. The figure is inverted, as it is shown in the instrument; one recognizes there also the extension and the limits of this nebula, the sensible difference between its clearest or most apparent light with that which merges gradually with the background of the sky. The jet of light, directed from the star no. 8 to the star no. 9, passing by a small star of the 10th magnitude, which is extremely rare, as well as the light directed to the star no. 10, and that which is opposite, where there are the eight stars contained in the nebula; among these stars, there is one of the eighth magnitude, six of the tenth, and the eighth of the eleventh magnitude. M. de Mairan, in his Traite de l’Aurore Boreale, speaks of the star no. 7. I report it in my drawing below such as it is at present, and as I have seen; so to speak surrounded by a thin nebulosity. In the night of October 14 to 15, 1764, in a serene sky, I determined with regard to Theta in the nebula, the positions of the more apparent stars in right ascension and declination, by the means of a micrometer adapted to a Newtonian telescope of 4 1/2 feet length. These stars are numbered up to ten; I have reported them in the drawing containing the field of the telescope; and an eleventh of them is beyond the circle. The positions of the stars which are not marked with numbers have been fixed by estimating their relative alignments. One will know easily also the magnitude of the Stars by the model which I have reported on the figure. Those of the tenth and the eleventh magnitude are absolutely telescopic and very difficult to find.”

However, it would be Sir William Herschel who would devote much love, time, and attention to the Great Orion Nebula – even though his findings would never be made public. As a true master observer, he had quite a talent for sensing what truly might lay beyond the boundary:

“In 1783, I reexamined the nebulous star, and found it to be faintly surrounded with a circular glory of whitish nebulosity, faintly joined to the great nebula. About the latter end of the same year I remarked that it was not equally surrounded, but most nebulous toward the south. In 1784 I began to entertain an opinion that the star was not connected with the nebulosity of the great nebula in Orion, but was one of those which are scattered over that part of the heavens. In 1801, 1806, and 1810 this opinion was fully confirmed, by the gradual change which happened in the great nebula, to which the nebulosity surrounding this star belongs. For the intensity of the light about the nebulous star had by this time been considerably reduced, by attenuation or dissipation of nebulous matter; and it seemed now to be pretty evident that the star is far behind the nebulous matter, and that consequently its light in passing through it is scattered and deflected, so as to produce the appearance of a nebulous star. A similar phenomenon may be seen whenever a planet or a star of the 1st or 2nd magnitude happens to be involved in haziness; for a diffused circular light will then be seen, to which, but in a much inferior degree, that which surrounds this nebulous star bears a great resemblance.”

But of course, the great Sir William Herschel also had nights from his many notes on M42 where he simply said: “The nebula in Orion which I saw by the front-view was so glaring and beautiful that I could not think of taking any place of its extent.”

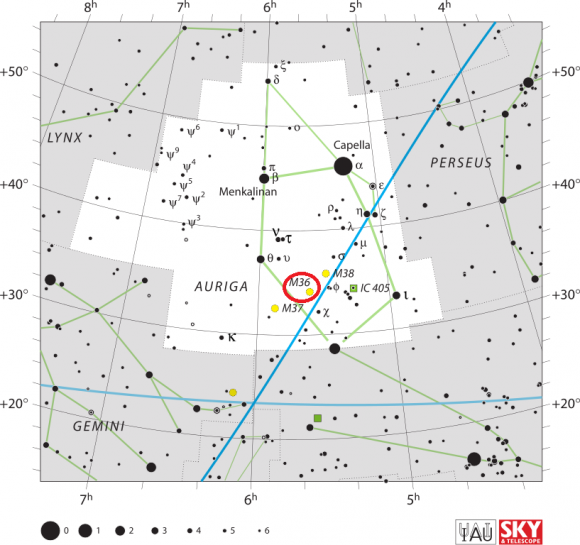

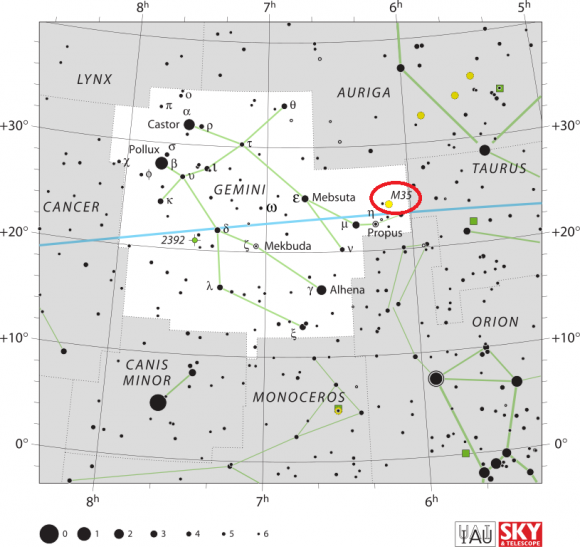

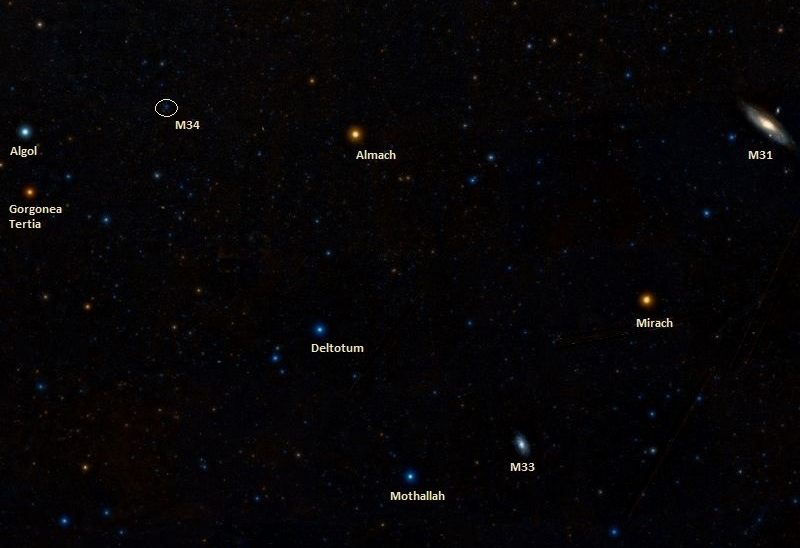

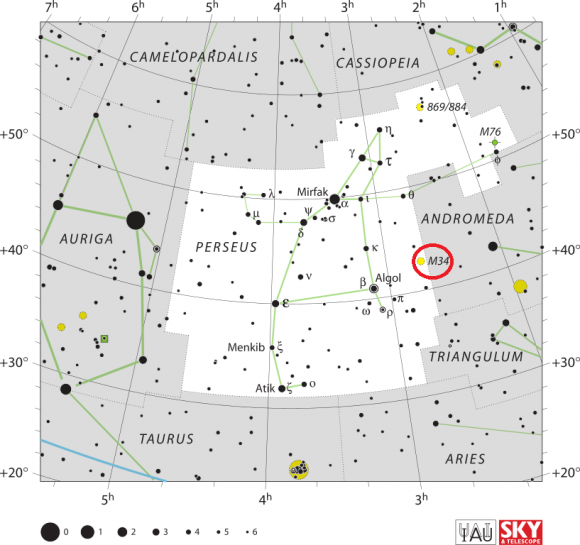

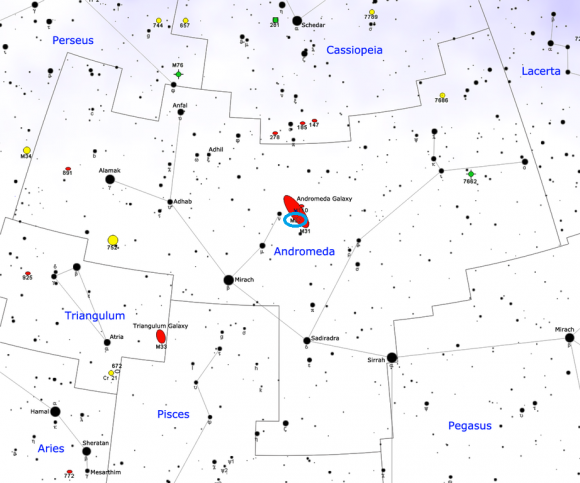

Locating Messier 42:

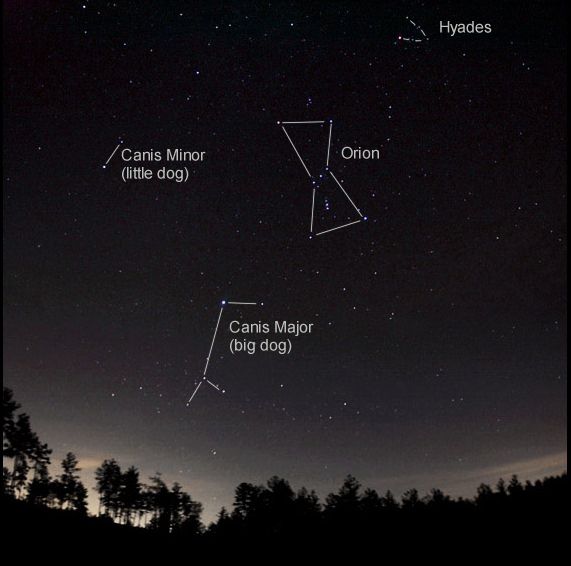

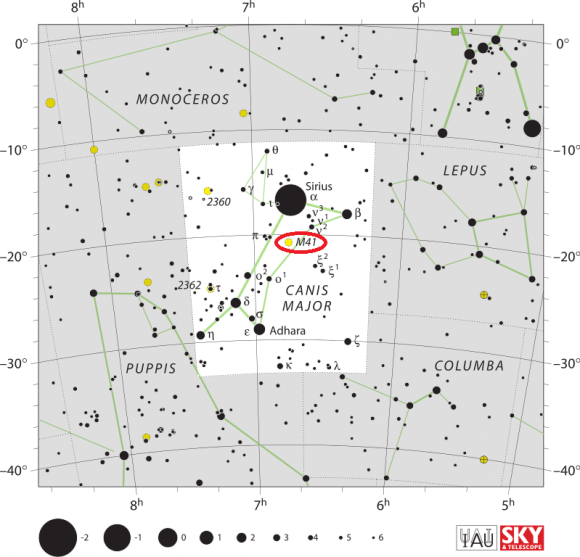

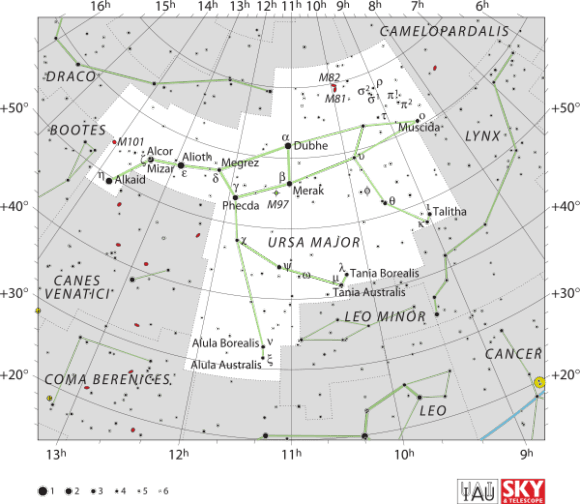

Finding Messier 42 is very easy from a dark sky location by centering on the glowing region in the center of Orion’s “sword”. However, from urban locations, these stars might not be visible, so aim your binoculars or telescope about a fist width south of the three prominent stars that make the asterism known as Orion’s Belt. It’s a very bright and large object well suited to all sky conditions and instruments!

Remember to use low power to get the full majesty of M42 and to increase magnification to study various regions. And trust us when we tell you, you are in for some pretty awesome viewing!

And of course, here are the quick facts on Messier 42 to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 42

Alternative Designations: M42, NGC 1976, The Great Orion Nebula, Home of the Trapezium

Object Type: Emission and Reflection Nebula with Open Galactic Star Cluster

Constellation: Orion

Right Ascension: 05 : 35.4 (h:m)

Declination: -05 : 27 (deg:m)

Distance: 1.3 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 4.0 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 85×60 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: