Since the beginning of the Space Age, humans have relied on chemical rockets to get into space. While this method is certainly effective, it is also very expensive and requires a considerable amount of resources. As we look to more efficient means of getting out into space, one has to wonder if similarly-advanced species on other planets (where conditions would be different) would rely on similar methods.

Harvard Professor Abraham Loeb and Michael Hippke, an independent researcher affiliated with the Sonneberg Observatory, both addressed this question in two recently–released papers. Whereas Prof. Loeb looks at the challenges extra-terrestrials would face launching rockets from Proxima b, Hippke considers whether aliens living on a Super-Earth would be able to get into space.

The papers, tiled “Interstellar Escape from Proxima b is Barely Possible with Chemical Rockets” and “Spaceflight from Super-Earths is difficult” recently appeared online, and were authored by Prof. Loeb and Hippke, respectively. Whereas Loeb addresses the challenges of chemical rockets escaping Proxima b, Hippke considers whether or not the same rockets would able to achieve escape velocity at all.

For the sake of his study, Loeb considered how we humans are fortunate enough to live on a planet that is well-suited for space launches. Essentially, if a rocket is to escape from the Earth’s surface and reach space, it needs to achieve an escape velocity of 11.186 km/s (40,270 km/h; 25,020 mph). Similarly, the escape velocity needed to get away from the location of the Earth around the Sun is about 42 km/s (151,200 km/h; 93,951 mph).

As Prof. Loeb told Universe Today via email:

“Chemical propulsion requires a fuel mass that grows exponentially with terminal speed. By a fortunate coincidence the escape speed from the orbit of the Earth around the Sun is at the limit of attainable speed by chemical rockets. But the habitable zone around fainter stars is closer in, making it much more challenging for chemical rockets to escape from the deeper gravitational pit there.”

As Loeb indicates in his essay, the escape speed scales as the square root of the stellar mass over the distance from the star, which implies that the escape speed from the habitable zone scales inversely with stellar mass to the power of one quarter. For planets like Earth, orbiting within the habitable zone of a G-type (yellow dwarf) star like our Sun, this works out quite while.

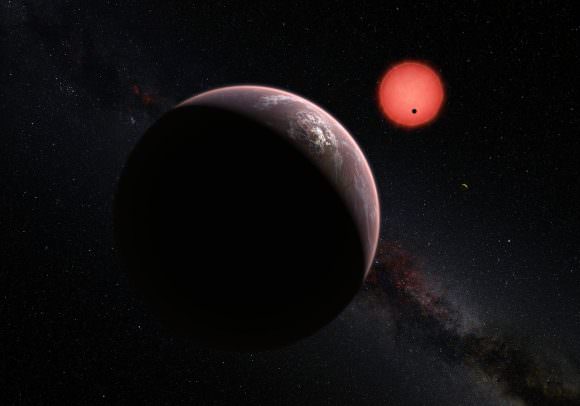

Unfortunately, this does not work well for terrestrial planets that orbit lower-mass M-type (red dwarf) stars. These stars are the most common type in the Universe, accounting for 75% of stars in the Milky Way Galaxy alone. In addition, recent exoplanet surveys have discovered a plethora of rocky planets orbiting red dwarf stars systems, with some scientists venturing that they are the most likely place to find potentially-habitable rocky planets.

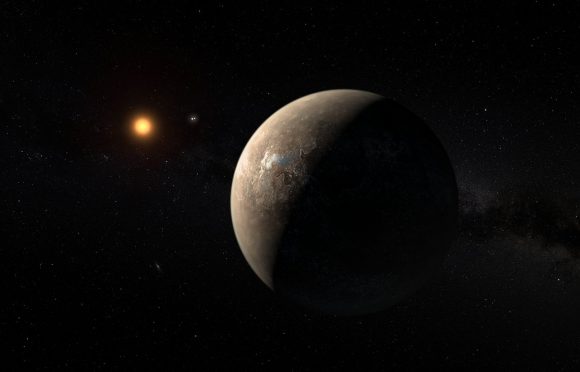

Using the nearest star to our own as an example (Proxima Centauri), Loeb explains how a rocket using chemical propellant would have a much harder time achieving escape velocity from a planet located within it’s habitable zone.

“The nearest star to the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is an example for a faint star with only 12% of the mass of the Sun,” he said. “A couple of years ago, it was discovered that this star has an Earth-size planet, Proxima b, in its habitable zone, which is 20 times closer than the separation of the Earth from the Sun. At that location, the escape speed is 50% larger than from the orbit of the Earth around the Sun. A civilization on Proxima b will find it difficult to escape from their location to interstellar space with chemical rockets.”

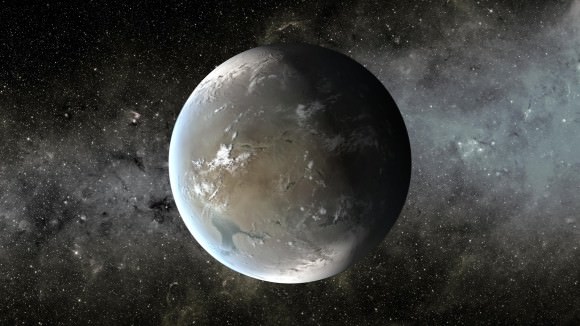

Hippke’s paper, on the other hand, begins by considering that Earth may in fact not be the most habitable type of planet in our Universe. For instance, planets that are more massive than Earth would have higher surface gravity, which means they would be able to hold onto a thicker atmosphere, which would provide greater shielding against harmful cosmic rays and solar radiation.

In addition, a planet with higher gravity would have a flatter topography, resulting in archipelagos instead of continents and shallower oceans – an ideal situation where biodiversity is concerned. However, when it comes to rocket launches, increased surface gravity would also mean a higher escape velocity. As Hippke indicated in his study:

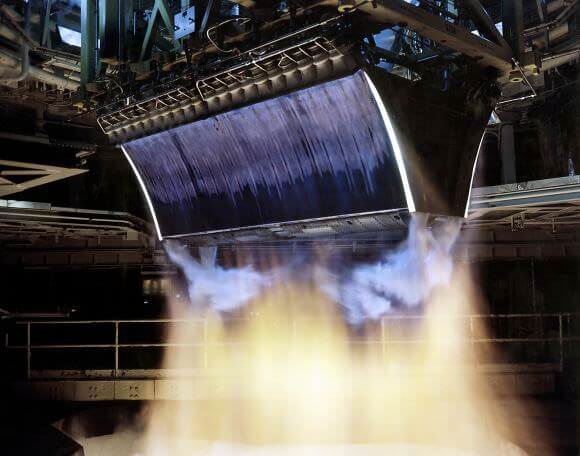

“Rockets suffer from the Tsiolkovsky (1903) equation : if a rocket carries its own fuel, the ratio of total rocket mass versus final velocity is an exponential function, making high speeds (or heavy payloads) increasingly expensive.”

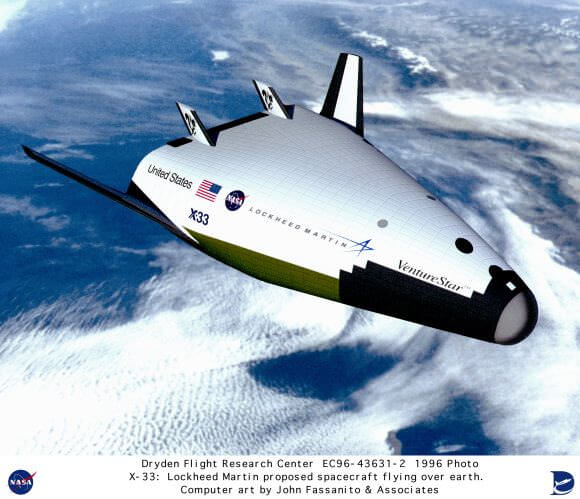

For comparison, Hippke uses Kepler-20 b, a Super-Earth located 950 light years away that is 1.6 times Earth’s radius and 9.7 times it mass. Whereas escape velocity from Earth is roughly 11 km/s, a rocket attempting to leave a Super-Earth similar to Kepler-20 b would need to achieve an escape velocity of ~27.1 km/s. As a result, a single-stage rocket on Kepler-20 b would have to burn 104 times as much fuel as a rocket on Earth to get into orbit.

To put it into perspective, Hippke considers specific payloads being launched from Earth. “To lift a more useful payload of 6.2 t as required for the James Webb Space Telescope on Kepler-20 b, the fuel mass would increase to 55,000 t, about the mass of the largest ocean battleships,” he writes. “For a classical Apollo moon mission (45 t), the rocket would need to be considerably larger, ~400,000 t.”

While Hippke’s analysis concludes that chemical rockets would still allow for escape velocities on Super-Earths up to 10 Earth masses, the amount of propellant needed makes this method impractical. As Hippke pointed out, this could have a serious effect on an alien civilization’s development.

“I am surprised to see how close we as humans are to end up on a planet which is still reasonably lightweight to conduct space flight,” he said. “Other civilizations, if they exist, might not be as lucky. On more massive planets, space flight would be exponentially more expensive. Such civilizations would not have satellite TV, a moon mission, or a Hubble Space Telescope. This should alter their way of development in certain ways we can now analyze in more detail.”

Both of these papers present some clear implications when it comes to the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence (SETI). For starters, it means that civilizations on planets that orbit red dwarf stars or Super-Earths are less likely to be space-faring, which would make detecting them more difficult. It also indicates that when it comes to the kinds of propulsion humanity is familiar with, we may be in the minority.

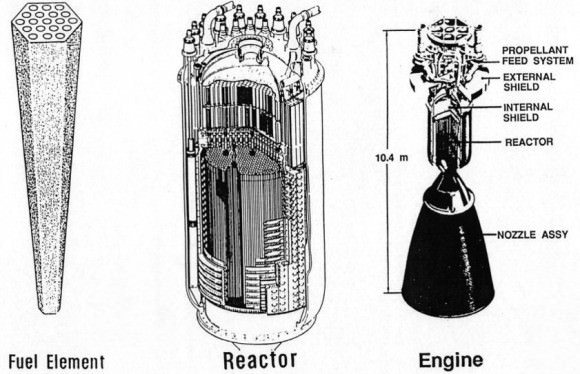

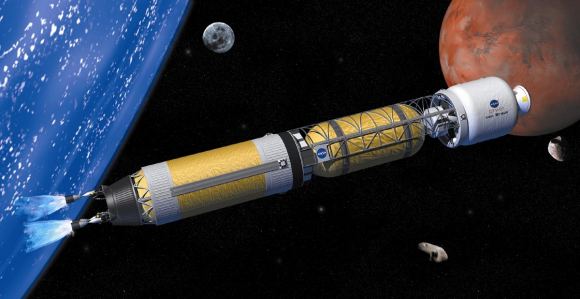

“This above results imply that chemical propulsion has a limited utility, so it would make sense to search for signals associated with lightsails or nuclear engines, especially near dwarf stars,” said Loeb. “But there are also interesting implications for the future of our own civilization.”

“One consequence of the paper is for space colonization and SETI,” added Hippke. “Civs from Super-Earths are much less likely to explore the stars. Instead, they would be (to some extent) “arrested” on their home planet, and e.g. make more use of lasers or radio telescopes for interstellar communication instead of sending probes or spaceships.”

However, both Loeb and Hippke also note that extra-terrestrial civilizations could address these challenges by adopting other methods of propulsion. In the end, chemical propulsion may be something that few technologically-advanced species would adopt because it is simply not practical for them. As Loeb explained:

“An advanced extraterrestrial civilization could use other propulsion methods, such as nuclear engines or lightsails which are not constrained by the same limitations as chemical propulsion and can reach speeds as high as a tenth of the speed of light. Our civilization is currently developing these alternative propulsion technologies but these efforts are still at their infancy.”

One such example is Breakthrough Starshot, which is currently being developed by the Breakthrough Prize Foundation (of which Loeb is the chair of the Advisory Committee). This initiative aims to use a laser-driven lightsail to accelerate a nanocraft up to speeds of 20% the speed of light, which will allow it to travel to Proxima Centauri in just 20 years time.

Hippke similarly considers nuclear rockets as a viable possibility, since increased surface gravity would also mean that space elevators would be impractical. Loeb also indicated that the limitations imposed by planets around low mass stars could have repercussions for when humans try to colonize the known Universe:

“When the sun will heat up enough to boil all water off the face of the Earth, we could relocate to a new home by then. Some of the most desirable destinations would be systems of multiple planets around low mass stars, such as the nearby dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 which weighs 9% of a solar mass and hosts seven Earth-size planets. Once we get to the habitable zone of TRAPPIST-1, however, there would be no rush to escape. Such stars burn hydrogen so slowly that they could keep us warm for ten trillion years, about a thousand times longer than the lifetime of the sun.”

But in the meantime, we can rest easy in the knowledge that we live on a habitable planet around a yellow dwarf star, which affords us not only life, but the ability to get out into space and explore. As always, when it comes to searching for signs of extra-terrestrial life in our Universe, we humans are forced to take the “low hanging fruit approach”.

Basically, the only planet we know of that supports life is Earth, and the only means of space exploration we know how to look for are the ones we ourselves have tried and tested. As a result, we are somewhat limited when it comes to looking for biosignatures (i.e. planets with liquid water, oxygen and nitrogen atmospheres, etc.) or technosignatures (i.e. radio transmissions, chemical rockets, etc.).

As our understanding of what conditions life can emerge under increases, and our own technology advances, we’ll have more to be on the lookout for. And hopefully, despite the additional challenges it may be facing, extra-terrestrial life will be looking for us!

Professor Loeb’s essay was also recently published in Scientific American.

Further Reading: arXiv, arXiv (2), Scientific American