Online science reporting is difficult. Never mind the incredible amount of work each story requires from interviewing scientists to meticulously choosing the words you will use to describe a tough subject. That’s the fun part. It’s just after you hit the blue publish button, when the story goes live, that things get rough. Your readers will tear you apart. They will comment on any misplaced commas, a number with one too many significant figures, and an added space in between sentences. They will criticize and not compliment.

Now I’m not saying this isn’t welcome. By all means if I have misspoken, do let me know. I need to be on top of my game 100% of the time and readers’ comments help make that happen. They can improve an article tremendously, allowing readers to carry on the conversation and provide a richer context. Thought-provoking commenters always bring a smile to my face.

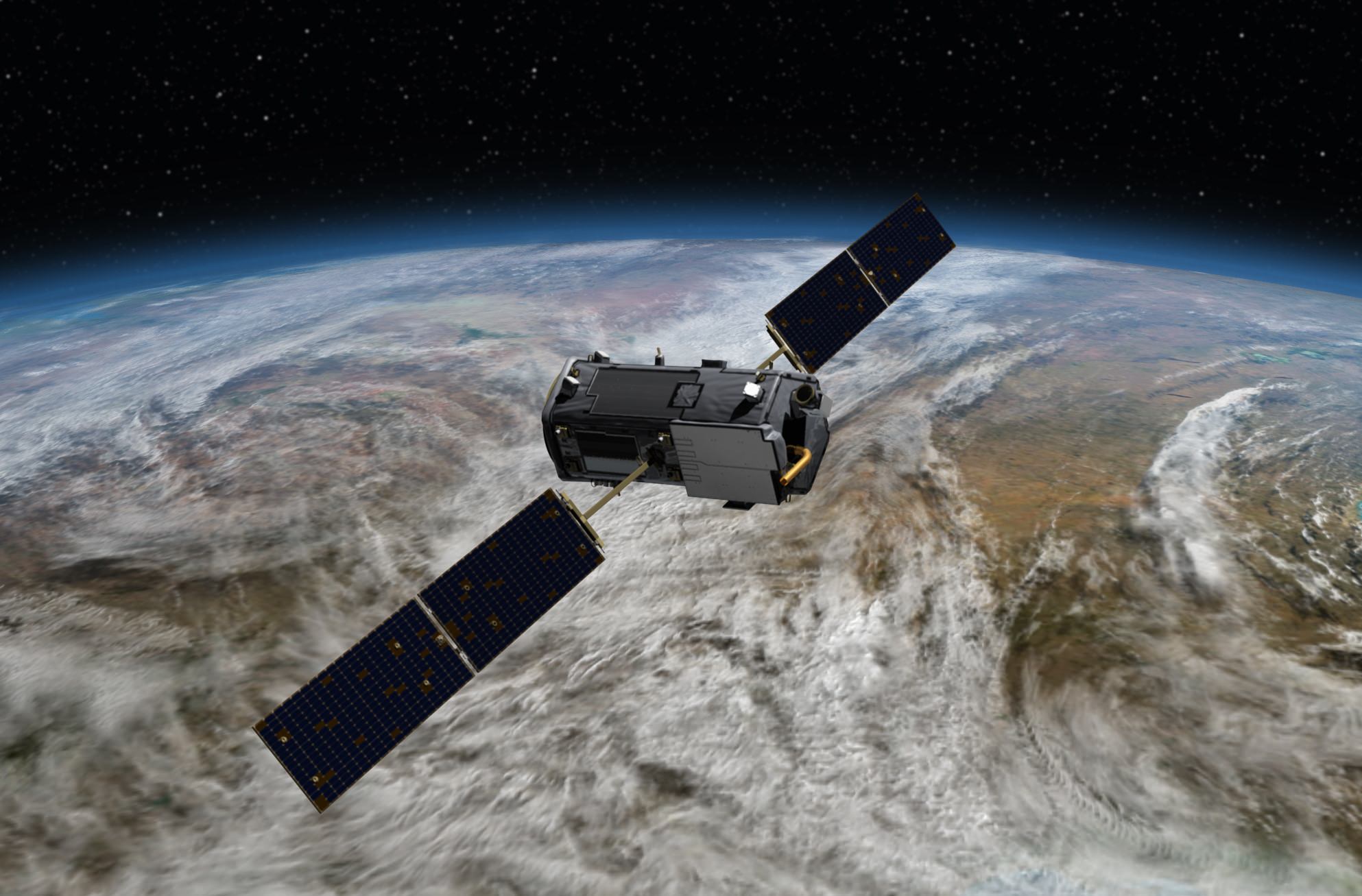

But then there’s online environmental reporting. From day one, reader comments made me realize that I needed to develop a thicker skin. I won’t go into the nasty details here, but in my most recent article, readers asked why Universe Today — an astronomy and space news site — would report on the science and even the politics regarding climate change. Well dear readers, I have heard you, and here is the answer to your question.

Universe Today is a dedicated space and astronomy news site. And I am proud to be a part of the team bringing readers up-to-date with the ongoings in our local universe. But that definition covers a wide variety of subjects, some might even say an infinite number of subjects.

On any given day authors from our team might write about subjects from planets within our solar system to distant galaxies. We want to better understand these celestial objects by focusing on their origin, evolution and fate. And in doing so we will discuss research that utilizes physics or chemistry, biology or astronomy. We might even write about politics, especially if NASA’s budget is involved.

I argue that writing about the Earth falls into the above category. After all, we do live on a planet that circles the Sun. And unlike Venus, where thick skies of carbon dioxide and even clouds of sulfuric acid make the surface incredibly difficult to see, we can directly study our surface, even run our fingers through the sand.

Intensive geologic surveys of the Earth below your feet help astronomers to understand the geology of other environments, including our nearest neighbor Venus and distant moons. We now know Enceladus has an ocean because of its combination of two compensating mass anomalies — an effect we see here on Earth. Perhaps one day this research will even help us understand geologic features on distant exoplanets.

Any study, which helps us better understand our home planet, whether it looks at plate tectonics or the sobering effects of global warming, exists under the encompassing umbrella of astronomy.

Now for my second, philosophical, argument. On the darkest of nights, thousands of stars compose the celestial sphere above us. The universe is boundless. It is infinite. We stand on but one out of 100 billion (if not more) planets in the Milky Way galaxy alone, which in turn, is but one out of 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe. We live in complete isolation. It’s both humbling and awe-inspiring.

Carl Sagan was the first to coin the phrase “pale blue dot” and in his words:

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Sagan argues that we have the moral duty to protect our home planet. This sense of obligation stems from the humble lessons gained from astronomy. So if Universe Today is not the appropriate platform to write about climate change I’m not sure what is.

All comments welcome.