[/caption]

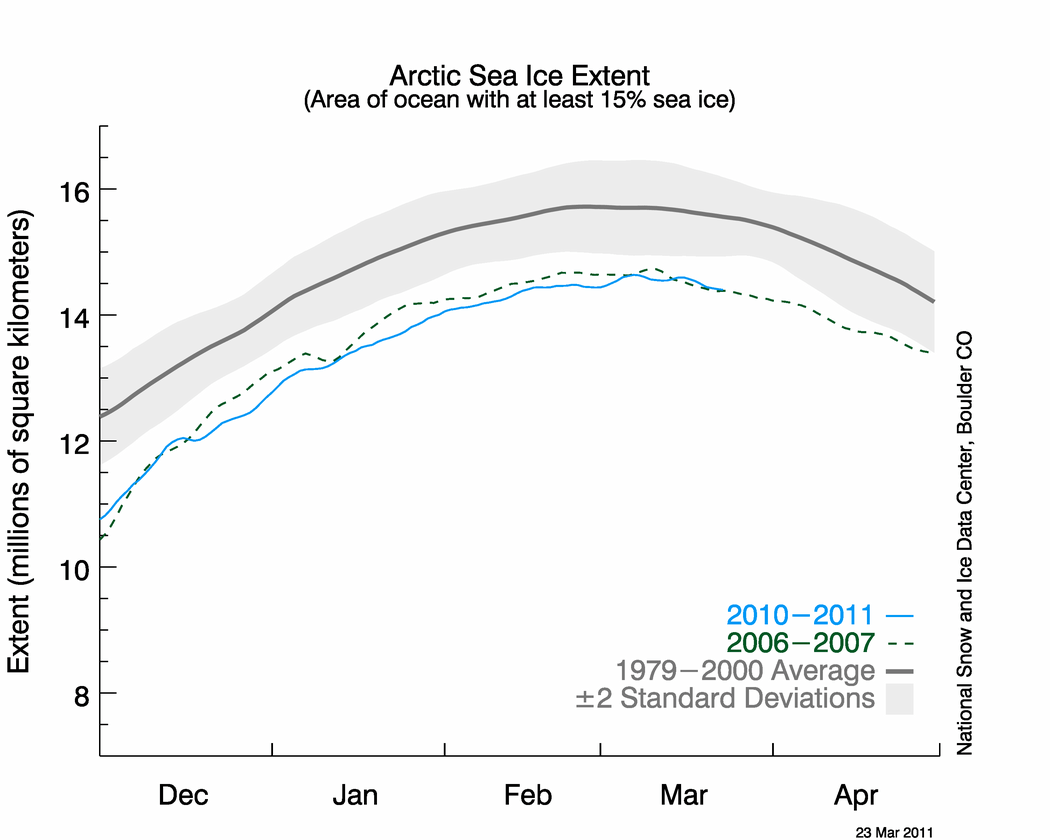

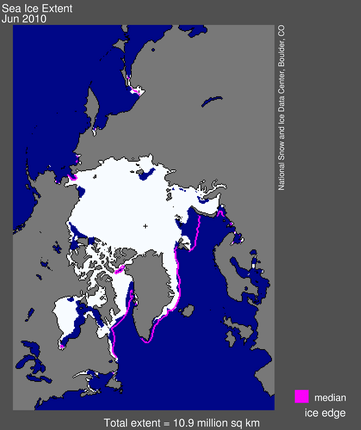

Bad news for what is now the beginning of the “melt season” in the Arctic. Right now, the sea ice extent maximum appears to be tied for the lowest ever measured by satellites as the spring begins, according to scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder’s National Snow and Ice Data Center. And because of the trend of how the amount of Arctic sea ice has been spiraling downward in the last decade, some scientists are predicting the Arctic Ocean may be ice free in the summers within the next several decades.

“I’m not surprised by the new data because we’ve seen a downward trend in winter sea ice extent for some time now,” said Walt Meier, a research scienitist with the NSIDC.

The seven lowest maximum Arctic sea ice extents measured by satellites all have occurred in the last seven years, and the from the latest data, the NSIDC research team believes the lowest annual maximum ice extent of 5,650,000 square miles occurred on March 7 of this year.

The maximum ice extent was 463,000 square miles below the 1979-2000 average, an area slightly larger than the states of Texas and California combined. The 2011 measurements were tied with those from 2006 as the lowest maximum sea ice extents measured since satellite record keeping began in 1979.

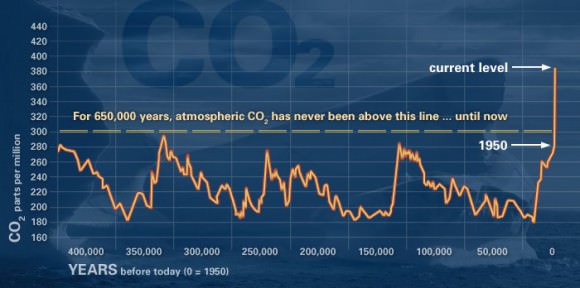

Virtually all climate scientists believe shrinking Arctic sea ice is tied to warming temperatures in the region caused by an increase in human-produced greenhouse gases being pumped into Earth’s atmosphere.

Meier said the Arctic sea ice functions like an air conditioner for the global climate system by naturally cooling air and water masses, playing a key role in ocean circulation and reflecting solar radiation back into space. In the Arctic summer months, sunlight is absorbed by the growing amounts of open water, raising surface temperatures and causing more ice to melt.

“I think one of the reasons the Arctic sea ice maximum extent is declining is that the autumn ice growth is delayed by warmer temperatures and the ice extent is not able to ‘catch up’ through the winter,” said Meier. “In addition, the clock runs out on the annual ice growth season as temperatures start to rise along with the sun during the spring months.”

Since satellite record keeping began in 1979, the maximum Arctic sea ice extent has occurred as early as Feb. 18 and as late as March 31, with an average date of March 6. Since the researchers determine the maximum sea ice extent using a five-day running average, there is small chance the data could change.

As of March 22, ice extent declined for five straight days. But February and March tend to be quite variable, so there is still a chance that the ice extent could expand again. Ice near the edge is thin and is highly sensitive to weather, scientists say, moving or melting quickly in response to changing winds and temperatures, and it often oscillates near the maximum extent for several days or weeks, as it has done this year.

In early April the NSIDC will issue a formal announcement on the 2011 maximum sea ice extent with a full analysis of the winter ice growth season, including graphics comparing 2011 to the long-term record.

Source: NSIDC, University of Colorado-Boulder