It’s official, for the first time ever, scientists have found a living organism on the Moon! Well, not so much found, we put it there. But the implications are immense nonetheless! According to photos and a statement released by the China National Space Administration this week (Mon. Jan. 14th), the Chang’e-4 mission’s Lunar Micro Ecosystem (LME) experiment has produced its first sprouted plant.

Continue reading “There’s Life on the Moon! China’s Lander Just Sprouted the First Plants”Here’s How to Follow the De-Orbit of Tiangong-1, now Estimated to Happen Between March 30 and April 2

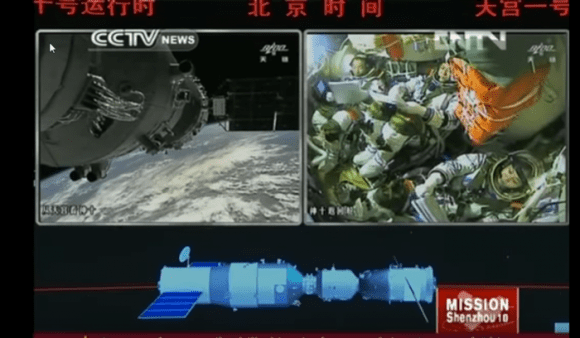

China’s Tiangong-1 space station has been the focus of a lot of international attention lately. In 2016, after four and half years in orbit, this prototype space station officially ended its mission. By September of 2017, the Agency acknowledged that the station’s orbit was decaying and that it would fall to Earth later in the year. Since then, estimates on when it will enter out atmosphere have been extended a few times.

According to satellite trackers, it was predicted that the station would fall to Earth in mid-March. But in a recent statement (which is no joke) the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) has indicated that Tiangong-1 will fall to Earth around April 1st – aka. April Fool’s Day. While the agency and others insists that it is very unlikely, there is a small chance that the re-entry could lead to some debris falling to Earth.

For the sake of ensuring public safety, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Space Debris Office (SDO) has been providing regular updates on the station’s decay. According to the SDO, the reentry window is highly variable and spans from the morning of March 31st to the afternoon of April 1st (in UTC time). This works out to the evening of March 30th or March 31st for people living on the West Coast.

As the ESA stated on their rocket science blog:

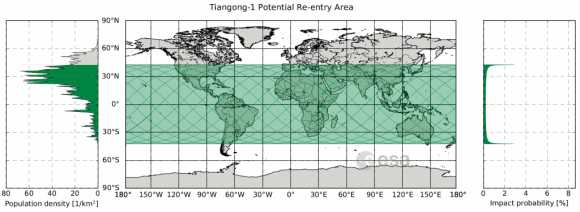

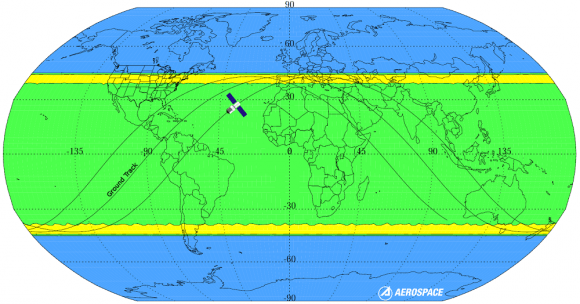

“Reentry will take place anywhere between 43ºN and 43ºS. Areas above or below these latitudes can be excluded. At no time will a precise time/location prediction from ESA be possible. This forecast was updated approximately weekly through to mid-March, and is now being updated every 1~2 days.”

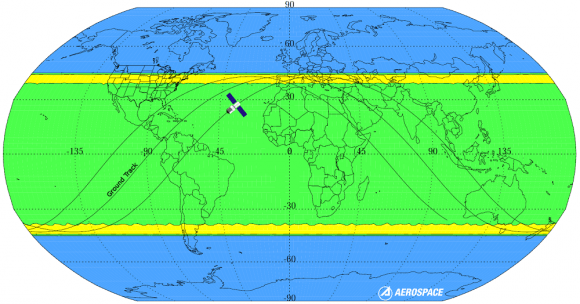

In other words, if any debris does fall to the surface, it could happen anywhere from the Northern US, Southern Europe, Central Asia or China to the tip of Argentina/Chile, South Africa, or Australia. Basically, it could land just about anywhere on the planet. On the other hand, back in January, the US-based Aerospace Corporation released a comprehensive analysis on Tiangong-1s orbital decay.

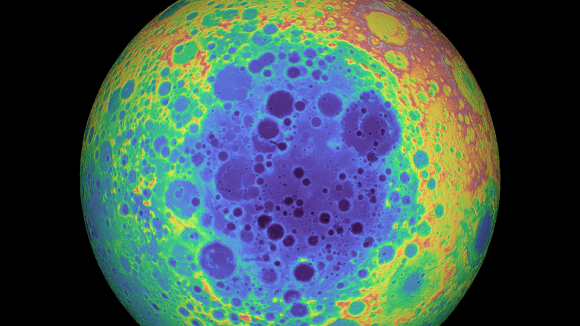

Their analysis included a map (shown below) which illustrated the zones of highest risk. Whereas the blue areas (that make up one-third of the Earth’s surface) indicate zones of zero probability, the green area indicates a zone of lower probability. The yellow areas, meanwhile, indicates zones that have a higher probability, which extend a few degrees south of 42.7° N and north of 42.7° S latitude, respectively.

The Aerospace Corporation has also created a dashboard for tracking Tiangong-1 (which is refreshed every few minutes) and has come to similar conclusions about the station’s orbital decay. Their latest prediction is that the station will descend into our atmosphere on April 1st, at 04:35 UTC (March 30th 08:35 PST), with a margin of error of about 24 hours – in other words, between March 30th to April 2nd.

And they are hardly alone when it comes to monitoring Tiangong-1’s orbit and predicting its descent. The China Human Spaceflight Agency (CMSA) recently began providing daily updates on the orbital status of Tiangong-1. As they reported on March 28th: “Tiangong-1 stayed at an average altitude of about 202.3 km. The estimated reentry window is between 31 March and 2 April, Beijing time.”

The US Space Surveillance Network, which is responsible for tracking artificial objects in Earth’s orbit, has also been monitoring Tiangong-1 and providing daily updates. Based on their latest tracking data, they estimate that the station will enter our atmosphere no later than midnight on April 3rd.

Naturally, one cannot help but notice that these predictions vary and are subject to a margin of error. In addition, trackers cannot say with any accuracy where debris – if any – will land on the planet. As Max Fagin – an aerospace engineer and space camp alumni – explained in a recent Youtube video (posted below), all of this arises from two factors: the station’s flight path and the Earth’s atmosphere.

Basically, the station is still moving at a velocity of 7.8 km/sec (4.8 mi/s) horizontally while it is descending by about 3 cm/sec. In addition, the Earth’s atmosphere shrinks and expands throughout the day in response to the Sun’s heating, which results in changes in air resistance. This makes the process of knowing where the station’s will make its descent difficult to predict, not to mention where debris could fall.

However, as Fagin goes on to explain, once the station reaches an altitude of 150 km (93 mi) – i.e. within the Thermosphere – it will begin falling much faster. At that point, it be much easier to determine where debris (if any) will fall. However, as the ESA, CNSA, and other trackers have emphasized repeatedly, the odds of any debris making it to the surface is highly unlikely.

If any debris does survive re-entry, it is also statistically likely to fall into the ocean or in a remote area – far away from any population centers. But in all likelihood, the station will break up completely in our atmosphere and produce a beautiful streaking effect across the sky. So if you’re checking the updates regularly and are in a part of the world where it can be seen, be sure to get outside and see it!

Further Reading: GB Times

China is Working on a Rocket as Powerful as the Saturn V, Could Launch by 2030

In the past decade, China’s space program has advanced by leaps and bounds. In recent years, the Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) has overseen the development of a modern rocket family (the Long March series), the deployment of a space station (Tiangong-1) and the development of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) – otherwise known as the Chang’e Program.

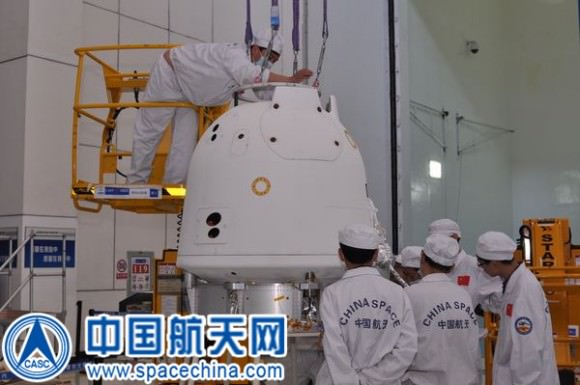

Looking to the future, China plans to create new classes of heavy rockets in order to conduct more ambitious missions. These include the Long March 9 rocket (aka. the Changzheng 9), a three-stage, super-heavy rocket that would allow for crewed missions to the Moon. According to a recent story from Aviation Weekly, China hopes to conduct an engine demonstration of this rocket, and could do so as early as later this year.

This demonstration is part of a research effort intended to create engines for the first stage of the Long March 9. According to statements made by the Academy of Aerospace Propulsion Technology (AAPT) – part of the China Aerospace and Technology Corporation (CASC) and the one’s responsible for developing the hardware – these engines would be capable of delivering 3,500 to 4,000 metric tons (3,858 to 4,409 US tons) of thrust.

AAPT also indicated that work on a second-stage and third-stage engine – which would be capable of generating about 200 metric tons (440,000 lbs) and 25 metric tons (55,000 lbs) thrust, respectively – is also in progress. All told, this is roughly six times the thrust that China’s heaviest rocket (the Long March 5) can generate and would make it comparable to the Saturn V – the Apollo-era rocket that took the NASA astronauts to the Moon.

For starters, the Saturn V‘s engines delivered roughly 3,400 metric tons of thrust, and the rocket was capable of delivering 140 metric tons (310,000 lbs) to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and about 48 metric tons (107,100 lbs) to a Lunar Transfer Orbit (LTO). By comparison, the Long March 9 will reportedly have the ability to 140 metric tons to LEO and at least 50 metric tons (110,000 lbs) to LTO.

According to Li Hong, the head of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (the CASC unit responsible for overall development and production of most Chinese space launchers), a massive turbopump has also been built for the main engine. A pump of this size is necessary, since the engine will generate four time the thrust of the largest Chinese rocket engine to date – AAPT’s YF-100, which generates 120 metric tons (265,000 lbs) of thrust.

While the full specifications of the rocket are not yet available, the China News Service has indicated that the rocket will measure 10 meters (33 ft.) in diameter. According to statements made by both Li and Lui, the first-stage engine will burn kerosene and achieve a thrust of 480 metric tons (529 US tons) – comparable to the Saturn V F-1 engine’s 680 metric tons (750 US tons) of thrust – while the second and third stage engines will likely burn hydrogen fuel.

At their current rate of progress, an engine demonstration could be taking place later this year. As AAPT President Liu Zhirang stated in an interview with Science and Technology Daily (part of the state-owned China News Service):

“A complete prototype for the engine in the 500-metric-ton class can be built and assembled this year… Because of the great parameter changes that come with rises in thrust, the current test and verification equipment cannot satisfy requirements [of the Moon rocket propulsion program]. We cannot always do 1:1 scale tests. As a result, only simulations and scaled-down tests can be done for some technology and hardware. This increases the degree of difficulty for the program.”

If successful, the Long March 9 will join the ranks of super heavy-lift launch vehicles, such as the SpaceX Falcon Heavy, the KRK rocket (currently under development in Russia), and the Space Launch System being developed by NASA. These and other rockets are being built for the purpose of bringing astronauts to the Moon, Mars, and even beyond in the coming decades.

Beyond a possible demonstration of the Long March 9′s engine technology, the CNSA has many other ambitious plans for 2018. These include a planned 35 launches involving the Long March series, fourteen of which will be carried out by the Long March-3A and six by the Long March-3C rockets. Most of these missions will involve the deployment of Beidou satellites, but will also include the launch of the Chang’e-4 lunar probe later this year.

This year is also when China hopes to conduct mission using its newest rocket – the Long March 5 – in preparation for China’s lunar probe and Mars probe missions. This year is also expected to see a lot of developments in the Long March 7 series, which is likely to become the main carrier when China begins construction of its new space station (Tiangong-2, which is scheduled for completion in 2022).

Between all of these developments, it is clear that the age of renewed space exploration is upon us. Whereas the Space Race was characterized by two superpowers competing for dominance and “getting their first”, the current one is defined by both competition and cooperation between multiple space agencies and lucrative partnerships between the public sector and private industry.

And while the specter of renewed competition by space powers has a tendency to make many people nervous (especially those who are concerned about military applications), it is a testament to how humanity is growing as a space-faring species. By the time 2050 rolls around, we may just see many flags being planted on the Moon and Mars, and not just Old Glory.

Further Reading: Aviation Week, Popular Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Upcoming Chinese Lander Will Carry Insects and Plants to the Surface of the Moon

It would be no exaggeration to say that we live in an age of renewed space exploration. In particular, the Moon has become the focal point of increasing attention in recent years. In addition to President Trump’s recent directive to NASA to return to the Moon, many other space agencies and private aerospace companies are planning their own missions to the lunar surface.

A good example is the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP), otherwise known as the Chang’e Program. Named in honor of the ancient Chinese lunar goddess, this program has sent two orbiters and one lander to the Moon already. And later this year, the Chang’e 4 mission will begin departing for the far side of the Moon, where it will study the local geology and test the effects of lunar gravity on insects and plants.

The mission will consist of a relay orbiter being launched aboard a Long March 5 rocket in June of 2018. This relay will assume orbit around the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange Point, followed by the launch of the lander and rover about six months later. In addition to an advanced suite of instruments for studying the lunar surface, the lander will also be carrying an aluminum alloy container filled with seeds and insects.

As Zhang Yuanxun – chief designer of the container – told the Chongqing Morning Post (according to China Daily):

“The container will send potatoes, arabidopsis seeds and silkworm eggs to the surface of the Moon. The eggs will hatch into silkworms, which can produce carbon dioxide, while the potatoes and seeds emit oxygen through photosynthesis. Together, they can establish a simple ecosystem on the Moon.”

The mission will also be the first time that a mission is sent to an unexplored region on the far side of the Moon. This region is none other than the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a vast impact region in the southern hemisphere. Measuring roughly 2,500 km (1,600 mi) in diameter and 13 kilometers (8.1 mi) deep, it is the single-largest impact basin on the Moon and one of the largest in the Solar System.

This basin is also source of great interest to scientists, and not just because of its size. In recent years, it has been discovered that the region also contains vast amounts of water ice. These are thought to be the results of impacts by meteors and asteroids which left water ice that survived because of how the region is permanently shadowed. Without direct sunlight, water ice in these craters has not been subject to sublimation and chemical dissociation.

Since the 1960s, several missions have explored this region from orbit, including the Apollo 15, 16 and 17 missions, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and India’s Chandrayaan-1 orbiter. This last mission (which was mounted in 2008) also involved sending the Moon Impact Probe to the surface to trigger the release of material, which was then analyzed by the orbiter.

The mission confirmed the presence of water ice in the Aitken Crater, a discovery which was confirmed about a year later by NASA’s LRO. Thanks to this discovery, there have been several in the space exploration community who have stated that the South Pole-Aitken Basin would be the ideal location for a lunar base. In this respect, the Chang’e 4 mission is investigating the very possibility of humans living and working on the Moon.

Aside from telling us more about the local terrain, it will also assess whether or not terrestrial organisms can grow and thrive in lunar gravity – which is about 16% that of Earths (or 0.1654 g). Previous studies conducted aboard the ISS have shown that long-term exposure to microgravity can have considerable health effects, but little is known about the long-term effects of lower gravity.

The European Space Agency has also been vocal about the possibility of building an International Lunar Village in the southern polar region by the 2030s. Intrinsic to this is the proposed Lunar Polar Sample Return mission, a joint effort between the ESA and Roscosmos that will involve sending a robotic probe to the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin by 2020 to retrieve samples of ice.

In the past, NASA has also discussed ideas for building a lunar base in the southern polar region. Back in 2014, NASA scientists met with Harvard geneticist George Church, Peter Diamandis (creator of the X Prize Foundation) and other parties to discuss low-cost options. According to the papers that resulted from the meeting, this base would exist at one of the poles and would be modeled on the U.S. Antarctic Station at the South Pole.

If all goes well for the Chang’e 4 mission, China intends to follow it up with more robotic missions, and an attempted crewed mission in about 15 years. There has also been talk about including a radio telescope as part of the mission. This RF instrument would be deployed to the far side of the Moon where it would be undistributed by radio signals coming from Earth (which is a common headache when it comes to radio astronomy).

And depending on what the mission can tell us about the South Pole-Aitken Basin (i.e. whether the water ice is plentiful and the radiation tolerable), it is possible that space agencies will be sending more missions there in the coming years. Some of them might even be carrying robots and building materials!

Further Reading: Sputnik News, Planetary Society

In mid-March, the Chinese Tiangong-1 Space Station is Going to Come Crashing Back Down to Earth… Somewhere

In September of 2011, China officially joined the Great Powers in Space club, thanks to the deployment of their Tiangong-1 space station. Since then, this prototype station has served as a crewed orbital laboratory and an experimental testbed for future space stations. In the coming years, China hopes to build on the lessons learned with Tiangong-1 to create a larger, modular station in 2023 (similar to the International Space Station).

Though the station’s mission was originally meant to end in 2013, the China National Space Agency extended its service to 2016. By September of 2017, the Agency acknowledged that they had lost control of the station and indicated that it would fall to Earth later in the year. According to the latest updates from satellite trackers, Tianglong-1 is likely to be reentering our atmosphere in March of 2018.

Given the fact that the station measures 10 by 3.35 meters (32.8 by 11 ft), weighs a hefty 8,506 kg (18,753 lb) and was built from very durable construction materials, there are naturally concerns that some of it might survive reentry and reach the surface. But before anyone starts worrying about space debris falling on their heads, there are a few things that need to be addressed.

For starters, in the history of space flight, there has not been a single confirmed death caused by falling space debris. Tthanks to the development of modern tracking and early warning systems, we are also more prepared than at any time in our history for the threat of falling debris. Statistically speaking, you are more likely to be hit by falling airplane debris or eaten by a shark.

Second, the CNSA has emphasized that the reentry is very unlikely to pose a threat to commercial aviation or cause any impact damage on the surface. As Wu Ping – the deputy director of the manned space engineering office – indicated at a press conference back on September 14th, 2017: “Based on our calculation and analysis, most parts of the space lab will burn up during falling.”

In addition, The Aerospace Corporation, which is currently monitoring the reentry of Tiangong-1, recently released the results of their comprehensive analysis. Similar to what Wu stated, they indicated that most of the station will burn up on reentry, though they acknowledged that there is a chance that small bits of debris could survive and reach the surface. This debris would likely fall within a region that is centered along the orbital path of the station (i.e. around the equator).

To illustrate the zones of highest risk, they produced a map (shown below) which indicates where the debris would be most likely to land. Whereas the blue areas (that make up one-third of the Earth’s surface) indicate zones of zero probability, the green area indicates a zone of lower probability. The yellow areas, meanwhile, indicates zones that have a higher probability, which extend a few degrees south of 42.7° N and north of 42.7° S latitude, respectively.

To add a little perspective to this analysis, the company also indicated the following:

“When considering the worst-case location (yellow regions of the map) the probability that a specific person (i.e., you) will be struck by Tiangong-1 debris is about one million times smaller than the odds of winning the Powerball jackpot. In the history of spaceflight, no known person has ever been harmed by reentering space debris. Only one person has ever been recorded as being hit by a piece of space debris and, fortunately, she was not injured.”

Last, but not least, the European Space Agency’s Inter Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) will be monitoring the reentry. In fact, the IADC – which is made up of space debris and other experts from NASA, the ESA, JAXA, ISRO, KARI, Roscosmos and the China National Space Administration – will be using this opportunity to conduct a test campaign.

During this campaign, participants will combine their predictions of the reentry’s time window, which are based on respective tracking datasets obtained from radar and other sources. Ultimately, the purpose of the campaign is to improve prediction accuracy for all member states and space agencies. And so far, their predictions also indicate that there is little cause for concern.

As Holger Krag, the Head of ESA’s Space Debris Office, indicated in a press statement back in November:

“Owing to the geometry of the station’s orbit, we can already exclude the possibility that any fragments will fall over any spot further north than 43ºN or further south than 43ºS. This means that reentry may take place over any spot on Earth between these latitudes, which includes several European countries, for example. The date, time and geographic footprint of the reentry can only be predicted with large uncertainties. Even shortly before reentry, only a very large time and geographical window can be estimated.”

The ESA’s Space Debris Office – which is based at the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany – will follow this campaign in February with an international expert workshop. This workshop (which will run from February 28th to March 1st, 2018) will focus on reentry predictions and atmospheric break-up studies and allow experts in the field of space debris monitoring to share their latest findings and research.

In the current age of renewed space exploration and rapidly improving technology, every new development in space is an opportunity to test the latest instruments and methods. The reentry of Tiangong-1 is a perfect example, where the reentry of a space station is being used to test our ability to predict falling space debris. It also highlights the need for tracking and monitoring, given that humanity’s presence in orbit is only going to increase in the coming years.

In the meantime, it would not be inadvisable to keep your eyes on the skies this coming March. While there is little chance that debris will pose a hazard, it is sure to be spectacular sight for people who live closer to the equator!

Further Reading: Aerospace.org, ESA, Xinhuanet

Europe & China Discuss Moonbase Partnership

In recent years, multiple space agencies have shared their plans to return astronauts to the Moon, not to mention establishing an outpost there. Beyond NASA’s plan to revitalize lunar exploration, the European Space Agency (ESA), Rocosmos, and the Chinese and Indian federal space agencies have also announced plans for crewed missions to the Moon that could result in permanent settlements.

As with all things in this new age of space exploration, collaboration appears to be the key to making things happen. This certainly seems to be the case when it comes to the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and the ESA’s respective plans for lunar exploration. As spokespeople from both agencies announced this week, the CNSA and the ESA hope to work together to create a “Moon Village” by the 2020s.

The announcement first came from the Secretary General of the Chinese space agency (Tian Yulong). On earlier today (Wednesday, April 26th) it was confirmed by the head of media relations for the ESA (Pal A. Hvistendahl). As Hvistendahl was quoted as saying by the Associated Press:

“The Chinese have a very ambitious moon program already in place. Space has changed since the space race of the ’60s. We recognize that to explore space for peaceful purposes, we do international cooperation.”

Yulong and Hvistendahl indicated that this base would aid in the development of lunar mining, space tourism, and facilitate missions deeper into space – particularly to Mars. It would also build upon recent accomplishments by both agencies, which have successfully deployed robotic orbiters and landers to the Moon in the past few decades. These include the CNSA’s Chang’e missions, as well as the ESA’s SMART-1 mission.

As part of the Chang’e program, the Chinese landers explored the lunar surface in part to investigate the prospect of mining Helium-3, which could be used to power fusion reactors here on Earth. Similarly, the SMART-1 mission created detailed maps of the northern polar region of the Moon. By charting the geography and illumination of the lunar north pole, the probe helped to identify possible base sites where water ice could be harvested.

While no other details of this proposed village have been released just yet, it is likely that the plan will build on the vision expressed by ESA director Jan Woerner back in December of 2015. While attending the “Moon 2020-2030 – A New Era of Coordinated Human and Robotic Exploration” symposium, Woerner expressed his agency’s desire to create an international lunar base as a successor to the International Space Station.

In addition, its is likely that the construction of this base will rely on additive manufacture (aka. 3-d printing) techniques specially developed for the lunar environment. In 2013, the ESA announced that they had teamed up with renowned architects Foster+Partners to test the feasibility of using lunar soil to print walls that would protect lunar domes from harmful radiation and micrometeorites.

This agreement could signal a new era for the CNSA, which has enjoyed little in the way of cooperation with other federal space agencies in the past. Due to the agency’s strong military connections, the U.S. government passed legislation in 2011 that barred the CSNA from participating in the International Space Station. But an agreement between the ESA and China could open the way for a three-party collaboration involving NASA.

The ESA, NASA and Roscosmos also entered into talks back in 2012 about the possibility of creating a lunar base together. Assuming that all four nations can agree on a framework, any future Moon Village could involve astronauts from all the world’s largest space agencies. Such a outpost, where research could be conducted on the long-term effects of exposure to low-g and extra-terrestrial environments, would be invaluable to space exploration.

In the meantime, the CNSA hopes to launch a sample-return mission to the Moon by the end of 2017 – Chang’e 5 – and to send the Chang’e 4 mission (whose launch was delayed in 2015) to the far side of the Moon by 2018. For its part, the ESA hopes to conduct a mission analysis on samples brought back by Chang’e 5, and also wants to send a European astronaut to Tiangong-2 (which just conducted its first automated cargo delivery) at some future date.

As has been said countless times since the end of the Apollo Era – “We’re going back to the Moon. And this time, we intend to stay!”

China Plans Lunar Far Side Landing by 2020

China plans lunar far side landing with hardware similar to Chang’e-3 lander

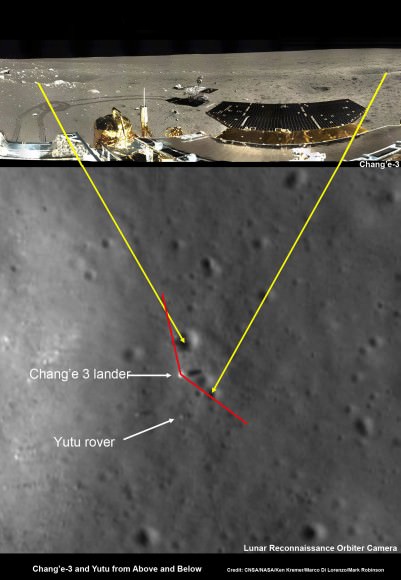

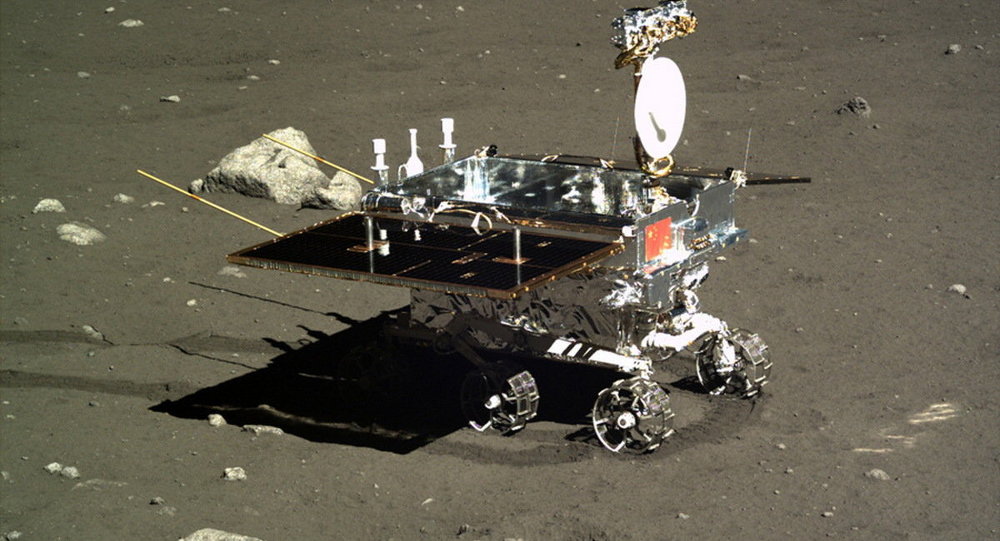

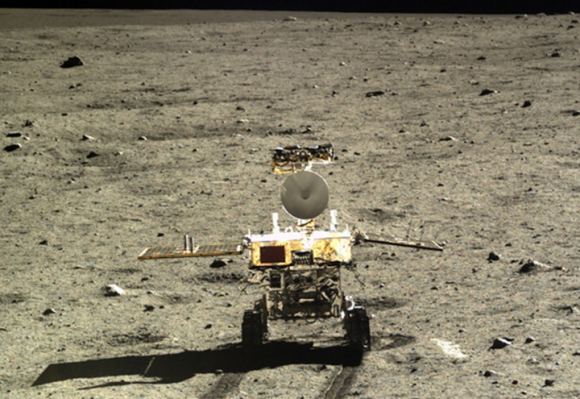

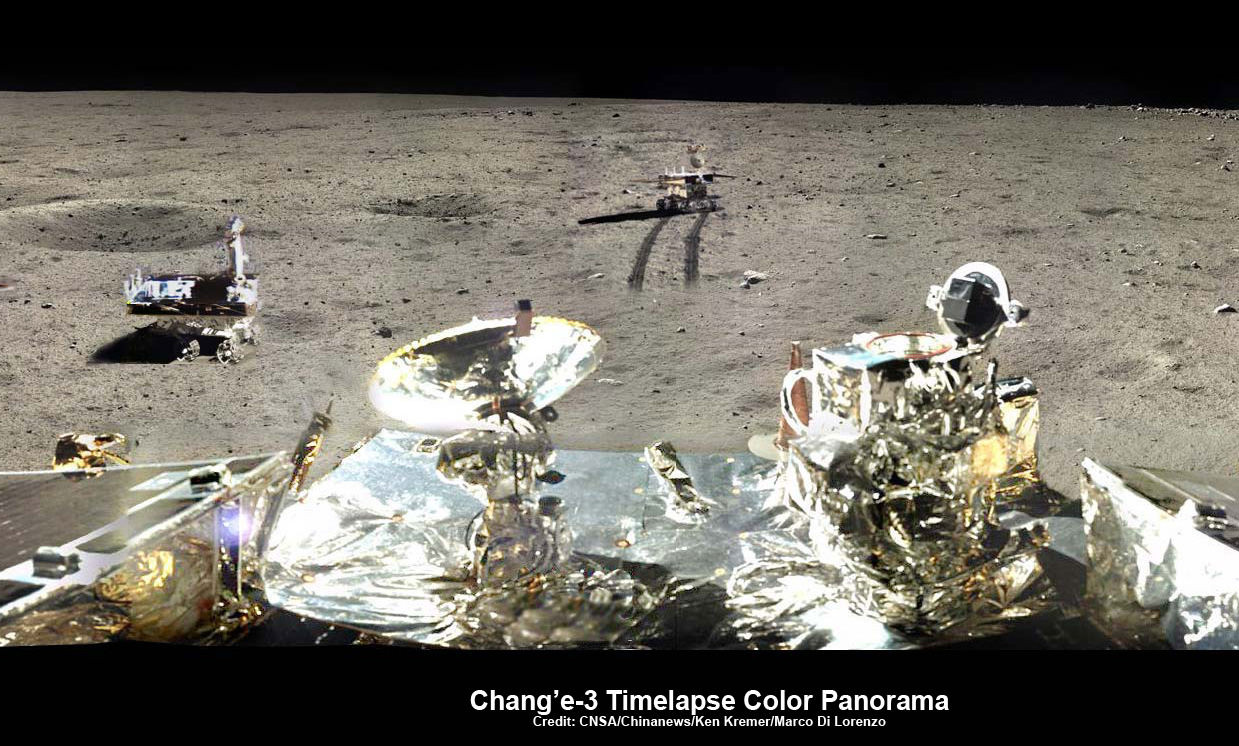

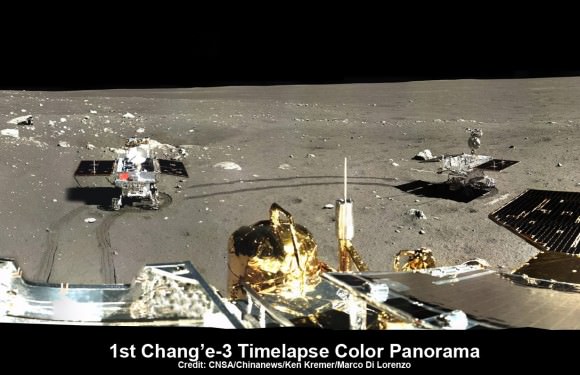

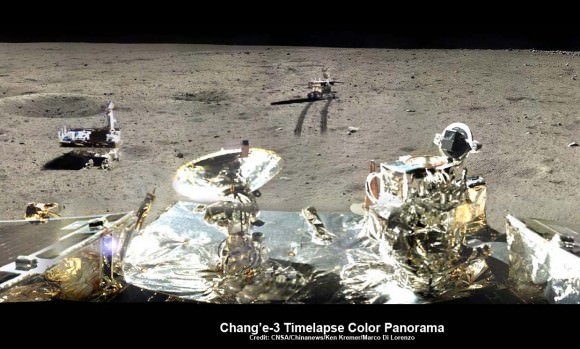

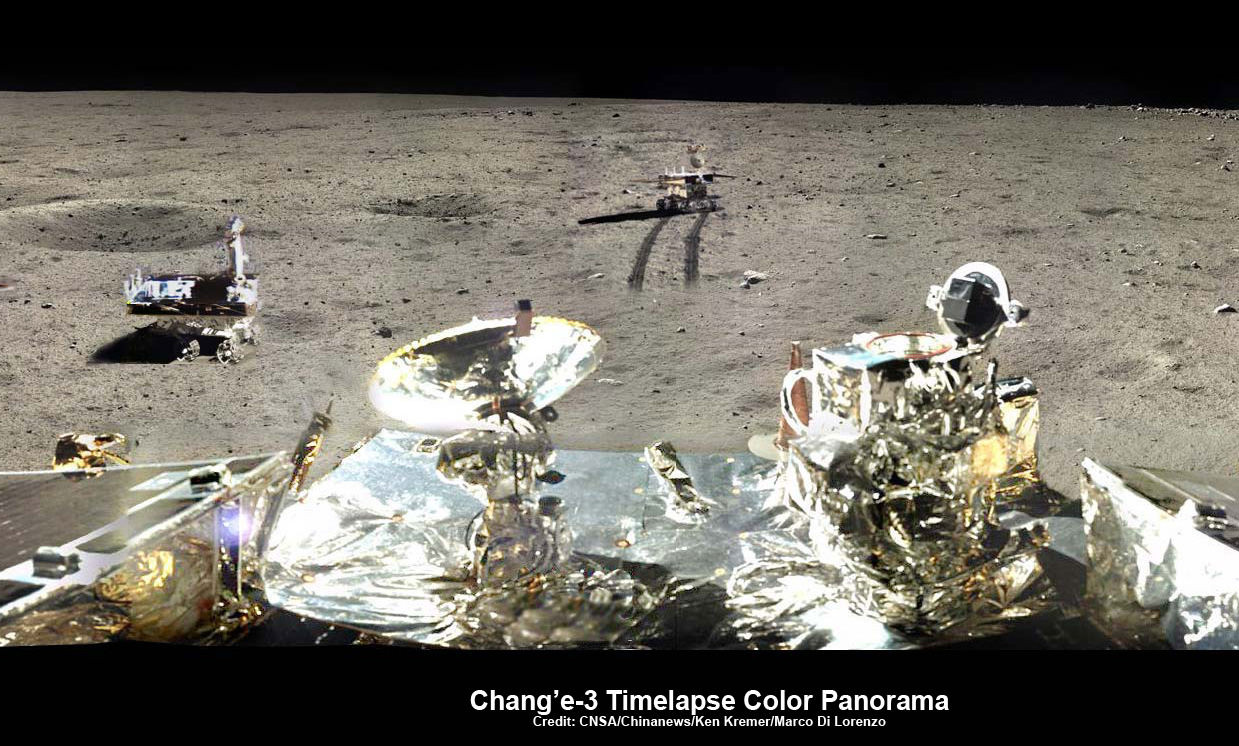

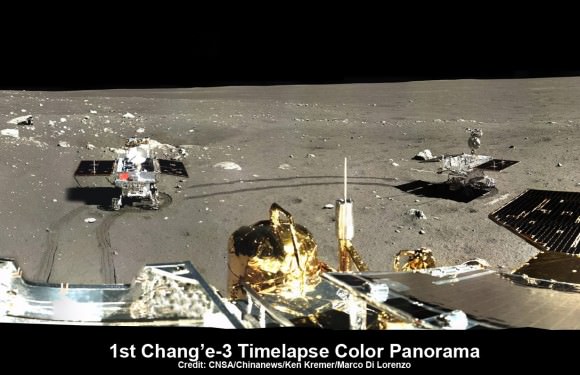

This time-lapse color panorama from China’s Chang’e-3 lander shows the Yutu rover at two different positions during its trek over the Moon’s surface at its landing site from Dec. 15-18, 2013. This view was taken from the 360-degree panorama. Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo.

See our complete Yutu timelapse pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: [/caption]

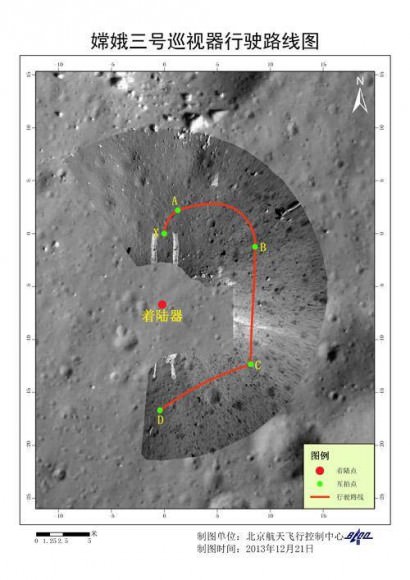

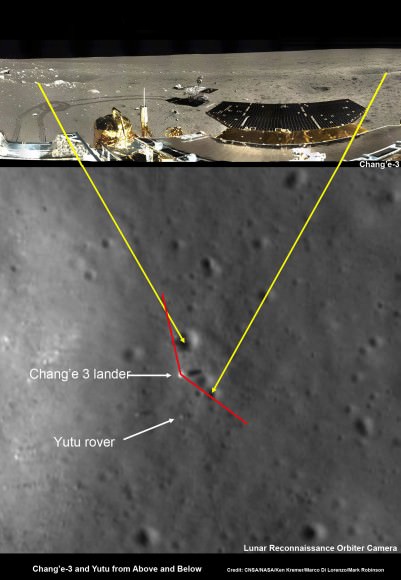

China aims to land a science probe and research rover on the far side of the Moon by 2020, say Chinese officials.

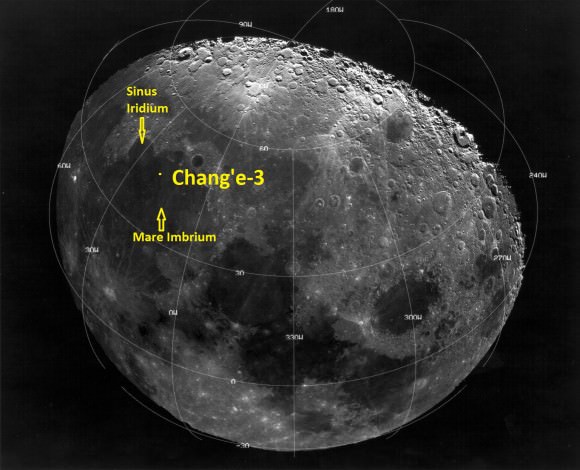

Chinese scientists plan to carry out the highly complex lunar landing mission using a near identical back up to the nations highly successful Chang’e-3 rover and lander – which touched down in December 2013.

If successful, China would become the first country to accomplish the history making task of a Lunar far side landing.

“The mission will be carried out by Chang’e-4, a backup probe for Chang’e-3, and is slated to be launched before 2020,” said Zou Yongliao from the moon exploration department under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, according to a recent report in China’s government owned Xinhua news agency.

Zou made the remarks at a deep-space exploration forum in China.

“China will be the first to complete the task if it is successful,” said Zou.

Chinese space scientists have been evaluating how best to utilize the Chang’e-4 hardware, built as a backup to Chang’e-3, ever since China’s successful inaugural soft landing on the Moon was accomplished by Chang’e-3 in December 2013 with the mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu lunar rover.

Plans to launch Chang’e-4 in 2016 were eventually abandoned in favor of further evaluation.

After completing an intense 12 month study ordered by China’s government, space officials confirmed that the lunar far side landing was the wisest use of the existing space hardware.

Chang’e-4 will be modified with a larger payload.

“Chang’e-4 is very similar to Chang’e-3 in structure but can handle more payload,” said Zou.

“It will be used to study the geological conditions of the dark side of the moon.”

The moon is tidally locked with the Earth so that only one side is ever visible. But that unique characteristic makes it highly attractive to scientists who have wanted to set up telescopes and other research experiments on the lunar far side for decades.

“The far side of the moon has a clean electromagnetic environment, which provides an ideal field for low frequency radio study. If we can can place a frequency spectrograph on the far side, we can fill a void,” Zou elaborated.

China will also have to launch another lunar orbiter in the next few years to enable the Chang’e-4 lander and rover to transmit signals and science data back to Chinese mission control on Earth.

In the meantime, China already announced its desire to forge ahead with an ambitious mission to return samples from the lunar surface later this decade.

The Chinese National Space Agency (CNSA) plans to launch the Chang’e-5 lunar sample return mission in 2017 as the third step in the nations far reaching lunar exploration program.

“Chang’e-5 will achieve several breakthroughs, including automatic sampling, ascending from the moon without a launch site and an unmanned docking 400,000 kilometers above the lunar surface,” said Li Chunlai, one of the main designers of the lunar probe ground application system, accoding to Xinhua.

The first step involved a pair of highly successful lunar orbiters named Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 which launched in 2007 and 2010.

The second step involved the hugely successful Chang’e-3 mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu moon rover which safely touched down on the Moon at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) on Dec. 14, 2013 – marking China’s first successful spacecraft landing on an extraterrestrial body in history, and chronicled extensively in my reporting here at Universe Today.

See above and herein our time-lapse photo mosaics showing China’s Yutu rover dramatically trundling across the Moon’s stark gray terrain in the first weeks after she rolled all six wheels onto the desolate lunar plains.

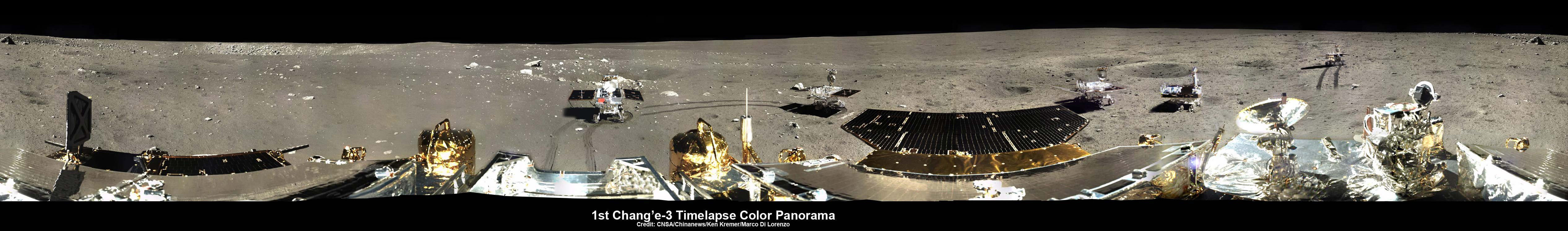

The complete time-lapse mosaic shows Yutu at three different positions trekking around the landing site, and gives a real sense of how it maneuvered around on its 1st Lunar Day.

The 360 degree panoramic mosaic was created by the imaging team of scientists Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo from images captured by the color camera aboard the Chang’e-3 lander and was featured at Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) on Feb. 3, 2014.

Chang’e-3 and Yutu landed on a thick deposit of volcanic material.

China is only the 3rd country in the world to successfully soft land a spacecraft on Earth’s nearest neighbor after the United States and the Soviet Union.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Chinese Unmanned Lunar Orbiter Returns Home Safely, Paves Path for Ambitious Lunar Sample Return

A Chinese robotic probe has just successfully completed the first round trip to the Moon and back home in four decades that paves the path for China’s next great space leap forward – an ambitious mission to return samples from the lunar surface later this decade.

On Saturday, Nov. 1, the unmanned Chang’e-5 T1 test capsule nicknamed “Xiaofei” concluded an eight-day test flight around the Moon by safely landing in Siziwang Banner of China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, according to a report by the official Xinhua News agency.

China thus become only the third nation to demonstrate lunar return technology following the former Soviet Union and the United States. The Soviet Union conducted the last lunar return mission in the 1970s.

Search teams with helicopters recovered the “Xiaofei” orbiter intact at the planned landing zone about 500 kilometers away from Beijing.

The Chang’e-5 T1 test mission is an unequivocally clear demonstration of China’s mounting technological prowess.

Chang’e-5 T1 served as a technology testbed and precursor flight for China’s planned Chang’e-5 probe, a future mission aimed at conducting China’s first lunar sample return mission in 2017.

“Chang’e-5 is expected to collect a 2-kg sample from two meters under the Moon’s surface and bring it home,” according to Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar exploration program.

The ability to gather and analyze pristine new soil and rocks samples from the Moon’s surface would be a boon for scientists worldwide seeking to unlock the mysteries of the solar system’s origin and evolution.

“Xiaofei” was launched on Oct. 23 EDT/Oct. 24 BJT atop an advanced Long March-3C rocket at 2 AM Beijing local time (BJT), 1800 GMT, from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China’s southwestern Sichuan Province.

It was boosted on an 840,000 kilometer, eight-day mission trajectory that swung halfway around the far side of the Moon and back. It did not enter lunar orbit.

During its path finding journey, “Xiaofei” captured incredible imagery of the Moon and Earth, eerie globes hanging together in the ocean of space.

The probe was developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. The service module is based on China’s earlier Chang’e-2 spacecraft.

On its return, the probe hit the Earth’s atmosphere at around 6:13 a.m. Saturday morning at about 11.2 kilometers per second for reentry and a parachute assisted soft landing in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

The goal was to test and validate guidance, navigation and control, heat shield, and trajectory design technologies required for the sample return capsule’s safe re-entry following a lunar touchdown mission and collection of soil and rock samples from the lunar surface – planned for the Chang’e-5 mission.

“To help it slow down, the craft is designed to ‘bounce’ off the edge of the atmosphere, before re-entering again. The process has been compared to a stone skipping across water, and can shorten the ‘braking distance’ for the orbiter,” according to Zhou Jianliang, chief engineer with the Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center.

“Really, this is like braking a car,” said Zhou, “The faster you drive, the longer the distance you need to bring the car to a complete stop.”

China hopes to launch the Chang’e-5 mission in 2017 as the third step in the nation’s ambitious lunar exploration program.

The first step involved a pair of highly successful lunar orbiters named Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 which launched in 2007 and 2010.

The second step involved the hugely successful Chang’e-3 mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu moon rover which safely touched down on the Moon at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) on Dec. 14, 2013 – marking China’s first successful spacecraft landing on an extraterrestrial body in history, and chronicled extensively in my reporting here.

See below our time-lapse photo mosaic showing China’s Yutu rover dramatically trundling across the Moon’s stark gray terrain in the first weeks after she rolled all six wheels onto the desolate lunar plains.

The complete time-lapse mosaic shows Yutu at three different positions trekking around the landing site, and gives a real sense of how it maneuvered around on its 1st Lunar Day.

The 360 degree panoramic mosaic was created by the imaging team of scientists Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo from images captured by the color camera aboard Chang’e-3 lander and was featured at Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) on Feb. 3, 2014.

China’s space officials are currently evaluating whether they will proceed with launching the Chang’e-4 lunar landing mission in 2016, which was a backup probe to Chang’e-3. Although Yutu was initially successful, it encountered difficulties about a month after rolling onto the surface which prevented it from roving across the surface and accomplishing some of its science objectives.

China is pushing forward with plans to start building a manned space station later this decade and considering whether to launch astronauts to the Moon by the mid 2020s or later.

Meanwhile, as American lunar and planetary missions sit still on the drawing board thanks to visionless US politicians, China continues to forge ahead with no end in sight.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

China’s Yutu Moon Rover Unable to Properly Maneuver Solar Panels

This time-lapse color panorama from China’s Chang’e-3 lander shows the Yutu rover at two different positions during its trek over the Moon’s surface at its landing site from Dec. 15-18, 2013. This view was taken from the 360-degree panorama.

Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo.

See our complete 5 position Yutu timelapse pano herein and 3 position pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140203.htm

Story updated[/caption]

The serious technical malfunction afflicting the life and continued operations of China’s Yutu moon rover since the start of its second Lunar Night time hibernation in late January 2014 has been identified as an inability to properly maneuver the life giving solar panels, according to a top Chinese space official.

“Yutu suffered a control circuit malfunction in its driving unit,” according to a newly published report on March 1 by the state owned Xinhua news agency.

“The control circuit problem prevented Yutu from entering the second dormancy as planned,” said Ye Peijian, chief scientist of the Chang’e-3 program, in an exclusive interview with Xinhua.

At the time that Yutu’s 2nd Lunar sleep period began on Jan. 25, 2014, Chinese space officials had announced that the robot’s future was in jeopardy after it suffered an unidentified “ mechanical control anomaly” due to the “complicated lunar surface.”

A functioning control circuit is required to lower the rovers mast and protect the delicate components and instruments mounted on the mast from directly suffering from the extremely harsh cold of the Moon’s recurring night time periods.

“Normal dormancy needs Yutu to fold its mast and solar panels,” said Ye.

The high gain communications antenna and the imaging cameras are attached to the mast.

They must be folded down into a warmed electronics box to shield them from the damaging effects of the Moon’s nightfall when temperatures plunge dramatically to below minus 180 Celsius, or minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit.

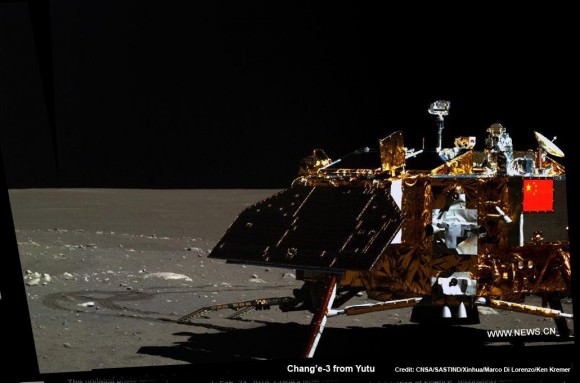

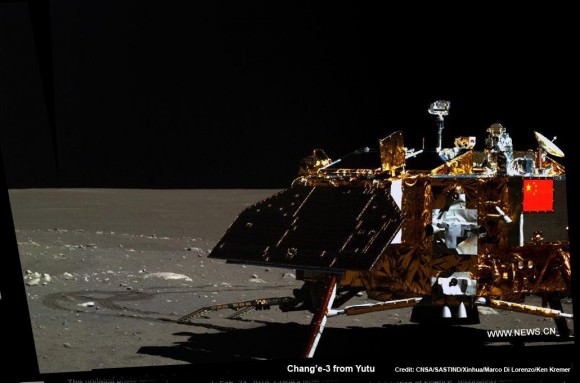

This newly expanded timelapse composite view shows China’s Yutu moon rover at two positions passing by crater and heading south and away from the Chang’e-3 lunar landing site forever about a week after the Dec. 14, 2013 touchdown at Mare Imbrium. This cropped view was taken from the 360-degree timelapse panorama. See complete 360 degree landing site timelapse panorama herein and APOD Feb. 3, 2014. Chang’e-3 landers extreme ultraviolet (EUV) camera is at right, antenna at left. Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo – kenkremer.com. See our complete Yutu timelapse pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140203.htm

The solar panels also generate power during each Lunar day to keep the robot alive and conduct its mission of scientific exploration roving across the lunar terrain.

The rover and Chang’e-3 stationary lander must power down and sleep during each lunar night since there is no sunlight available to generate power and no communications are possible with Earth.

The panel driving unit also helps maneuver the panels into position to efficiently point to the sun to maximize the electrical output.

“The driving unit malfunction prevented Yutu to do those actions” said Ye.

Each lunar day and night lasts for alternating periods of 14 Earth days.

“This means Yutu had to go through the lunar night in extremely low temperatures.”

Apparently the mast was not retracted and remained vertical during the lunar nights 2 and 3.

And the camera somehow survived the harsh temperature decline and managed to continue operating since it snapped two images of the Chan’ge-3 lander during Lunar Day 3. See our two image mosaic – below.

In addition to being chief scientist of the Chang’e-3 program Ye is also a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s top political advisory body.

Yutu is China’s first ever Moon rover and successfully accomplished a soft landing on the Moon on Dec. 14, 2013, piggybacked atop the Chang’e-3 mothership lander.

Barely seven hours after touchdown, the six wheeled moon buggy drove down a pair of ramps onto the desolate gray plains of the lunar surface at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) covered by volcanic material.

For a time in mid-February, mission scientists feared that Yutu would no longer function when because no signals were received until two days later than the planned “awakening” from Lunar Night 2 on Feb. 10.

Fortunately, Yutu did finally wake up some 48 hours late on Feb. 12 and function on Lunar Day 3.

And the team engaged in troubleshooting to try and identify and rectify the technical problems.

Since then, Chinese space engineers engaged in troubleshooting to try and identify and rectify the technical problems in a race against time to find a solution before the start of Lunar Night 3.

The 140 kilogram rover was unable to move during Lunar Day 3 due to the mechanical glitches.

“Yutu only carried out fixed point observations during its third lunar day.” according to China’s State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence (SASTIND), responsible for the mission.

However it did complete some limited scientific observations. And fortunately the ground penetrating radar, panoramic and infrared imaging equipment all functioned normally.

Yutu and the companion Chang’e-3 lander have again gone into sleep mode during Lunar Night 3 on Feb. 22 and Feb 23 respectively, local Beijing time.

But the issue with the control circuit malfunction in its driving unit remains unresolved and still threatens the outlook for Yutu’s future exploration.

See our new Chang’e-3/Yutu lunar panoramas by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo herein and at NASA APOD on Feb. 3, 2014.

Yutu is now nearing its planned 3 month long life expectancy on a moon roving expedition to investigate the moon’s surface composition and natural resources.

The 1200 kg stationary lander is functioning normally. It is as expected to return science data about the Moon and conduct telescopic observations of the Earth and celestial objects for at least one year.

Yutu, which translates as ‘Jade Rabbit’ is named after the rabbit in Chinese mythology that lives on the Moon as a pet of the Moon goddess Chang’e.

“We all wish it would be able to wake up again,” said Ye according to CCTV, China’s state run broadcaster.

Ye will be reporting about Yutu and the Chang’e-3 mission at the annual session of the top advisory body, which opened today, Monday, March 3.

China is only the 3rd country in the world to successfully soft land a spacecraft on Earth’s nearest neighbor after the United States and the Soviet Union.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Chang’e-3, Orion, Orbital Sciences, SpaceX, commercial space, Curiosity, GPM, LADEE, Mars and more planetary and human spaceflight news. Learn more at Ken’s upcoming presentations at the NEAF convention on April 12/13.

Yutu Moon Rover Starts 3rd Night Time Hibernation But Technical Problems Persist

Chang’e-3/Yutu Timelapse Color Panorama

This newly expanded timelapse composite view shows China’s Yutu moon rover at two positions passing by crater and heading south and away from the Chang’e-3 landing site forever about a week after the Dec. 14, 2013 touchdown at Mare Imbrium. This cropped view was taken from the 360-degree timelapse panorama. See complete 360 degree landing site timelapse panorama herein and APOD Feb. 3, 2014. . Chang’e-3 landers extreme ultraviolet (EUV) camera is at right, antenna at left. Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo – kenkremer.com.

See our complete Yutu timelapse pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140203.htm

Story updated[/caption]

The world famous and hugely popular ‘Yutu’ rover entered its 3rd Lunar night time hibernation period this weekend as planned, but serious technical troubles persist that are hampering science operations Chinese space managers confirmed.

“China’s lunar rover Yutu entered its third planned dormancy on Saturday, with the mechanical control issues that might cripple the vehicle still unresolved,” reports Xinhua, China’s official government news agency, in a mission status update newly released today (Feb. 23).

Yutu went to sleep on Saturday afternoon, Feb. 22, local Beijing time, according to China’s State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence (SASTIND), responsible for the mission.

The companion Chang’e-3 lunar lander entered hibernation soon thereafter early today, Sunday, Feb 23.

See our new lunar panoramas by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo herein and at NASA APOD on Feb. 3, 2014.

This new 360-degree time-lapse color panorama from China’s Chang’e-3 lander shows the Yutu rover at five different positions, including passing by crater and heading south and away from the Chang’e-3 lunar landing site forever during its trek over the Moon’s surface at its landing site from Dec. 15-22, 2013 during the 1st Lunar Day. Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo – kenkremer.com. See our Yutu timelapse pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140203.htm

Yutu first encountered a serious technical malfunction a month ago on Jan. 25, when she suffered ‘a mechanical control anomoly’ just prior to entering hibernation for the duration of Lunar Night 2.

The abnormality occurred due to the “complicated lunar surface,” according to SASTIND.

New mosaic of the Chang’e-3 moon lander and the lunar surface taken by the camera on China’s Yutu moon rover from a position south of the lander. Note the landing ramp and rover tracks at left. Credit: CNSA/SASTIND/Xinhua/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer – kenkremer.com

Chinese space officials have not divulged the exact nature of the problems. And they have not released any details of the efforts to resolve the issues that “might cripple the vehicle.”

Since both Chinese Moon probes are solar powered, they must power down and enter a dormant mode during every two week long lunar night period when there is no sunlight to generate energy from their solar arrays. And no communications with Earth are possible.

The rover, nicknamed ‘Jade Rabbit’ remained stationary during the just concluded two week long lunar day time period, said SASTIND. It was unable to move due to the mechanical glitches.

“Yutu only carried out fixed point observations during its third lunar day.”

But it did complete some limited scientific observations. And fortunately the ground penetrating radar, panoramic and infrared imaging equipment are functioning normally.

The six wheel robot’s future was placed in jeopardy after it suffered the “mechanical anomaly” in late January 2014 and then awoke later than the scheduled time on Feb. 10, at the start of its 3rd Lunar Day.

To the teams enormous relief, a signal was finally detected.

“Yutu has come back to life!” said Pei Zhaoyu, the spokesperson for China’s lunar probe program, according to a Feb. 12 news report by the state owned Xinhua news agency.

“Experts are still working to verify the causes of its mechanical control abnormality.”

This 360-degree time-lapse color panorama from China’s Chang’e-3 lander shows the Yutu rover at three different positions during its trek over the Moon’s surface at its landing site from Dec. 15-22, 2013 during the 1st Lunar Day. Credit: CNSA/Chinanews/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo – kenkremer.com. See our Yutu timelapse pano at NASA APOD Feb. 3, 2014: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap140203.htm

Since then, Chinese space engineers sought to troubleshoot the technical problems and were in a race against time to find a solution before the start of Lunar Night 3 this weekend.

“Experts had feared that it might never function again, but Yutu “woke up” on Feb. 12, two days behind schedule,” reported Xinhua.

Each lunar day and night lasts for alternating periods of 14 Earth days.

During each long night, the Moon’s temperatures plunge dramatically to below minus 180 Celsius, or minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit.

Both solar powered probes must enter hibernation mode during each lunar night to conserve energy and protect their science instruments and control mechanisms, computers and electronics.

“Scientists are still trying to find a fix for the abnormalities,” said CCTV, China’s official state television network.

So Yutu is now sleeping with the problems unresolved and no one knows what the future holds.

Hopefully Jade Rabbit awakes again in about two weeks time to see the start of Lunar Day 4.

The Chang’e-3 mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu surface rover soft landed on the Moon on Dec. 14, 2013 at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) – marking China’s first successful spacecraft landings on an extraterrestrial body in history.

‘Jade Rabbit’ had departed the landing site forever, and was journeying southwards as the anomoly occurred – about six weeks into its planned 3 month long moon roving expedition to investigate the moon’s surface composition and natural resources.

The 140 kg Yutu robot is located some 100 m south of the lander.

The 1200 kg stationary lander is expected to return science data about the Moon and conduct telescopic observations of the Earth and celestial objects for at least one year.

Chang’e-3 and Yutu landed on a thick deposit of volcanic material.

China is only the 3rd country in the world to successfully soft land a spacecraft on Earth’s nearest neighbor after the United States and the Soviet Union.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Chang’e-3, Orion, Orbital Sciences, SpaceX, commercial space, LADEE, Mars and more planetary and human spaceflight news.