When traveling to far off lands, one packs carefully. What you carry must be comprehensive but not so much that it is a burden. And once you arrive, you must be prepared to do something extraordinary to make the long journey worthwhile.

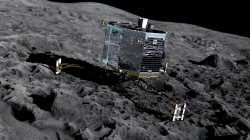

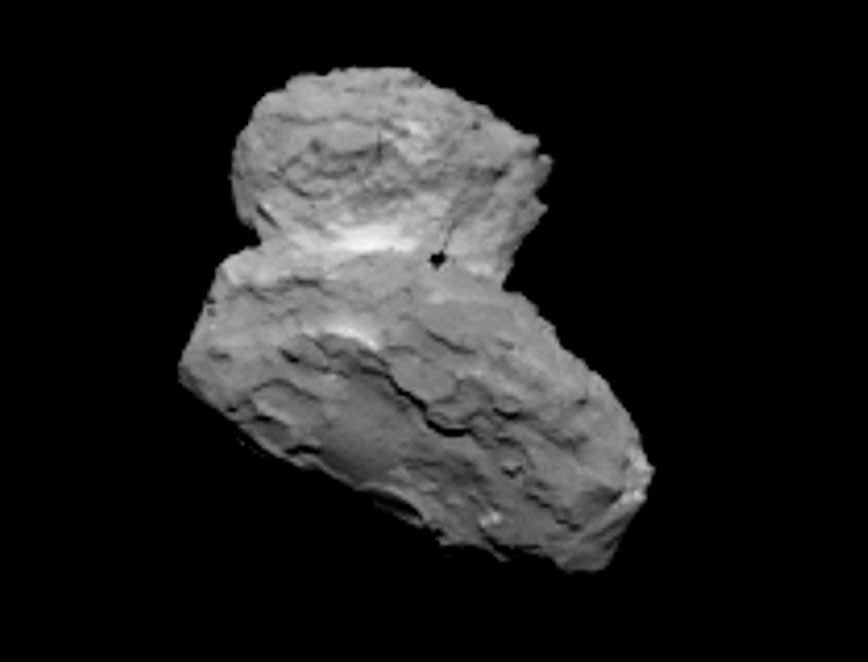

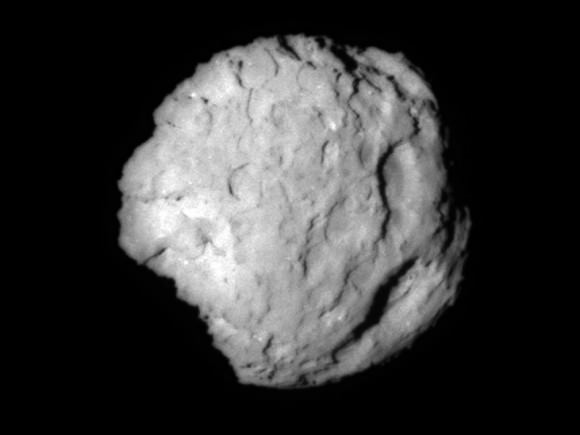

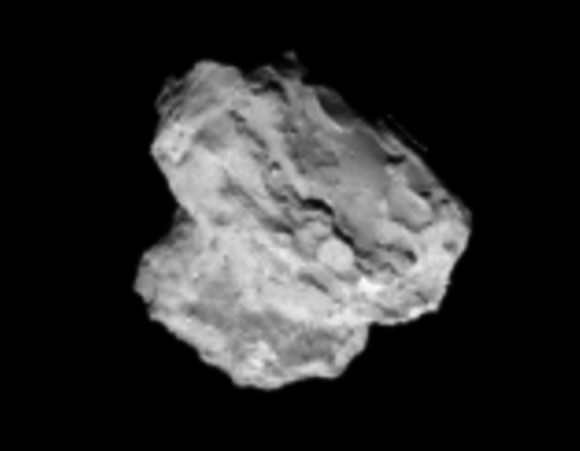

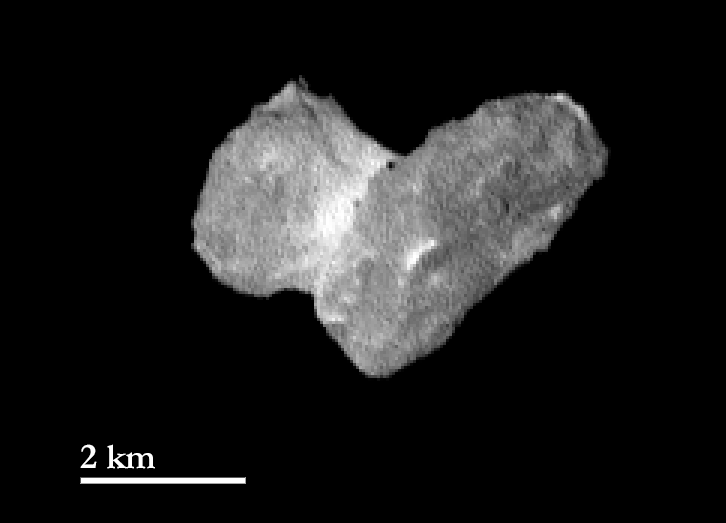

The previous Universe Today article “How do you land on a Comet?” described Philae’s landing technique on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. But what will the lander do once it arrives and gets settled in its new surroundings? As Henry David Thoreau said, “It is not worthwhile to go around the world to count the cats in Zanzibar.” So it is with the Rosetta lander Philae. With the stage set – a landing site chosen and landing date of November 11th, the Philae lander is equipped with a carefully thought-out set of scientific instruments. Comprehensive and compact, Philae is a like a Swiss Army knife of tools to undertake the first on-site (in-situ) examination of a comet.

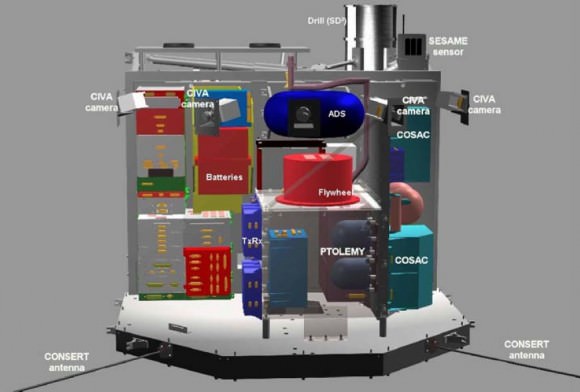

Now, consider the scientific instruments on Philae which were selected about 15 years ago. Just like any good traveler, budgets had to be set which functioned as constraints on the instrument selection that could be packed and carried along on the journey. There was a maximum weight, maximum volume, and power. The final mass of Philae is 100 kg (220 lbs). Its volume is 1 × 1 × 0.8 meters (3.3 × 3.3 × 2.6 ft) about the size of a four burner oven-range. However, Philae must function on a small amount of stored energy upon arrival: 1000 Watt-Hours (equivalent of a 100 watt bulb running for 10 hours). Once that power is drained, it will produce a maximum of 8 watts of electricity from Solar panels to be stored in a 130 Watt-Hour battery.

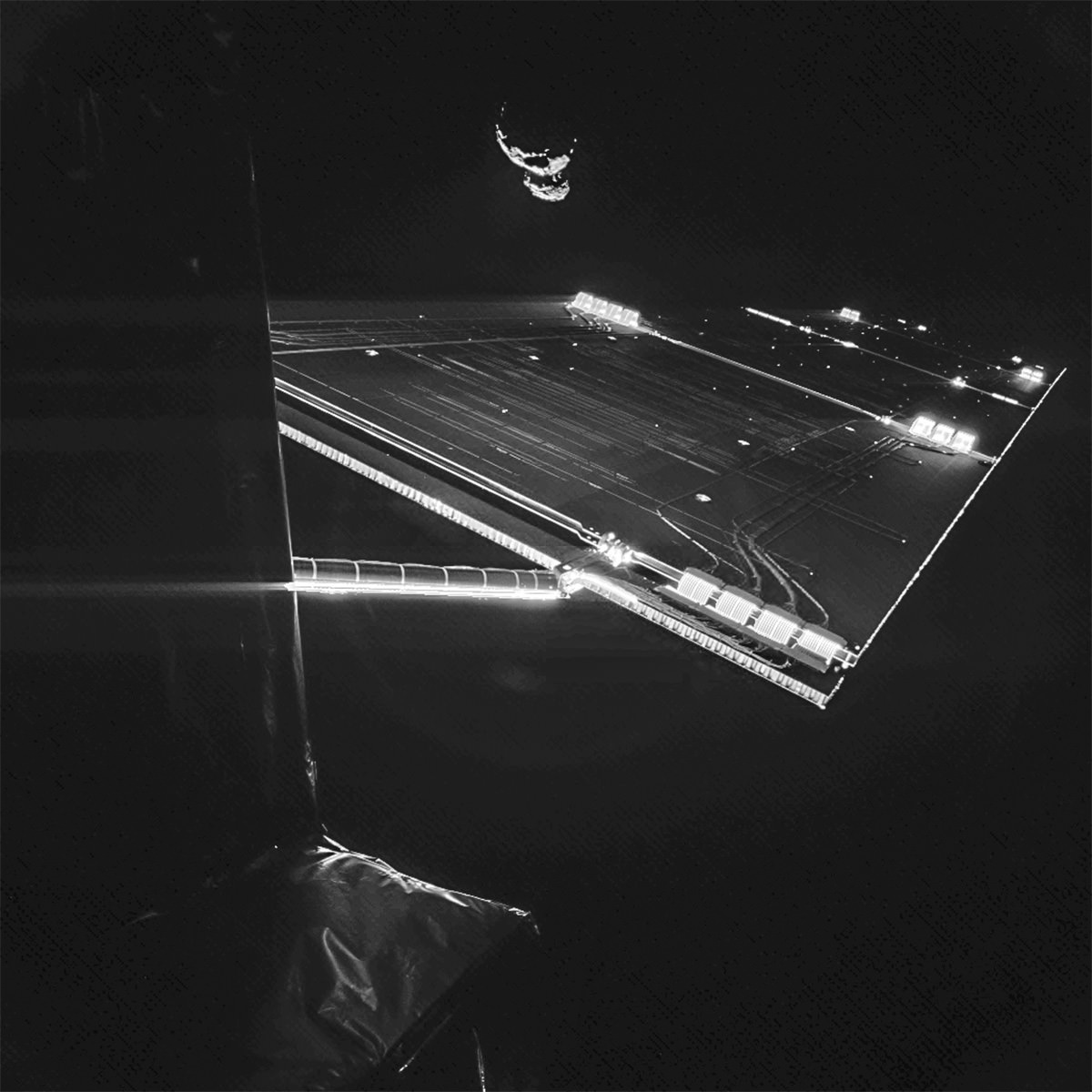

Without any assurance that they would land fortuitously and produce more power, the Philae designers provided a high capacity battery that is charged, one time only, by the primary spacecraft solar arrays (64 sq meters) before the descent to the comet. With an initial science command sequence on-board Philae and the battery power stored from Rosetta, Philae will not waste any time to begin analysis — not unlike a forensic analysis — to do a “dissection” of a comet. Thereafter, they utilize the smaller battery which will take at least 16 hours to recharge but will permit Philae to study 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko for potentially months.

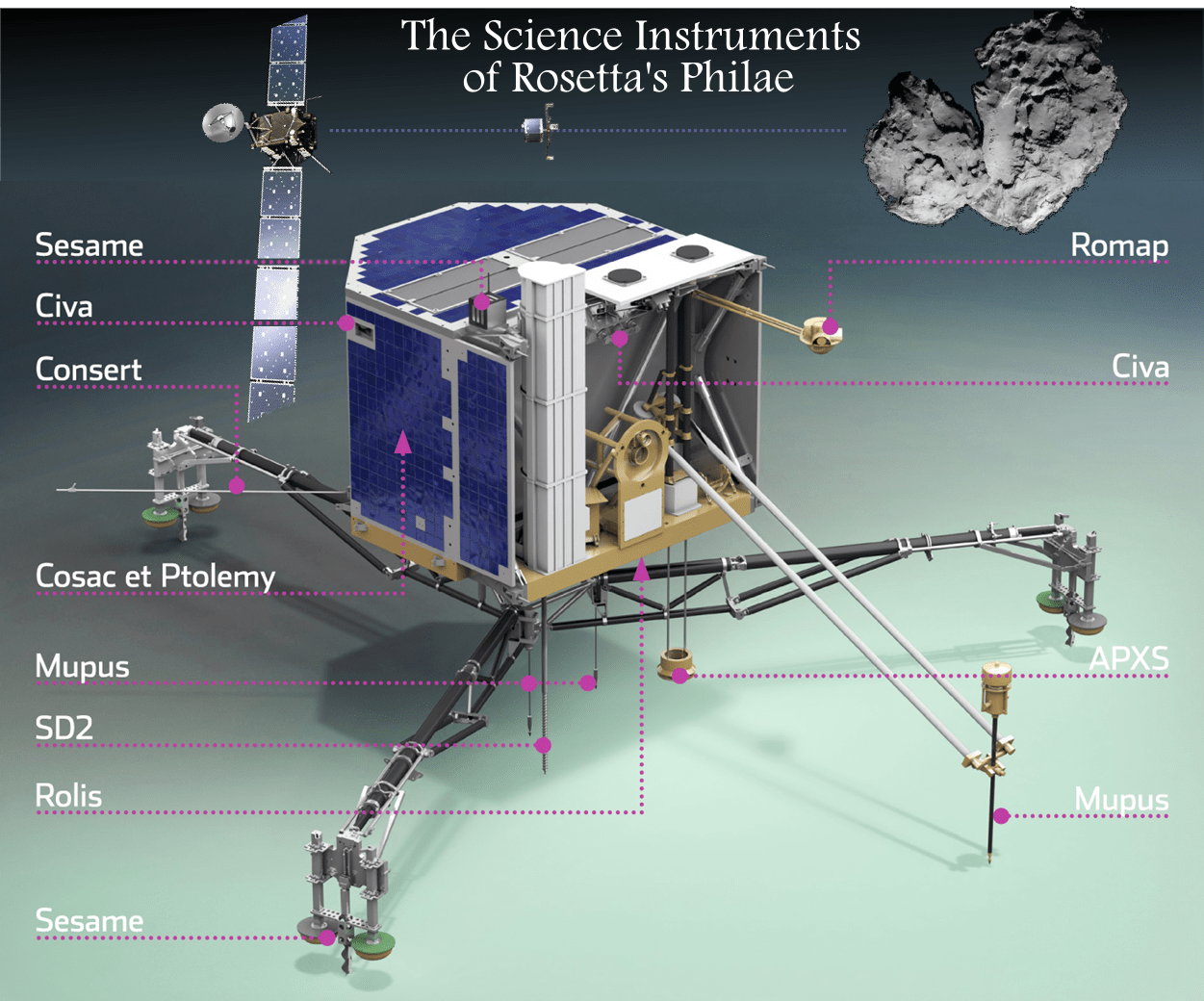

There are 10 science instrument packages on the Philae lander. The instruments use absorbed, scattered, and emitted light, electrical conductivity, magnetism, heat, and even acoustics to assay the properties of the comet. Those properties include the surface structure (the morphology and chemical makeup of surface material), interior structure of P67, and the magnetic field and plasmas (ionized gases) above the surface. Additionally, Philae has an arm for one instrument and the Philae main body can be rotated 360 degrees around its Z-axis. The post which supports Philae and includes a impact dampener.

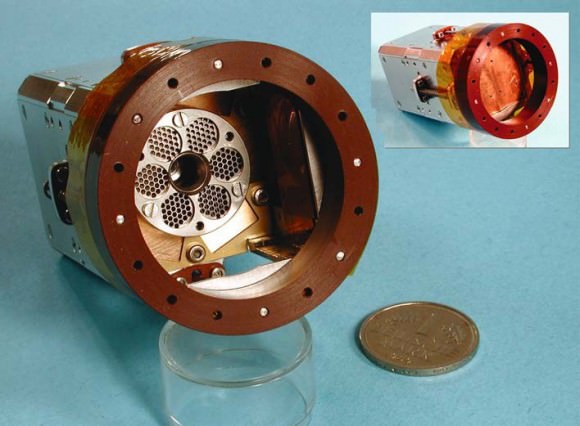

CIVA and ROLIS imaging systems. CIVA represents three cameras which share some hardware with ROLIS. CIVA-P (Panoramic) is seven identical cameras, distributed around the Philae body but with two functioning in tandem for stereo imaging. Each has a 60 degree field of view and uses as 1024×1024 CCD detector. As most people can recall, digital cameras have advanced quickly in the last 15 years. Philae’s imagers were designed in the late 1990s, near state-of-the-art, but today they are surpassed, at least in number of pixels, by most smartphones. However, besides hardware, image processing in software has advanced as well and the images may be enhanced to double their resolution.

CIVA-P will have the immediate task, as part of the initial autonomous command sequence, of surveying the complete landing site. It is critical to the deployment of other instruments. It will also utilize the Z-axis rotation of the Philae body to survey. CIVA-M/V is a microscopic 3-color imager (7 micron resolution) and CIVA-M/I is a near infra-red spectrometer (wavelength range of 1 to 4 microns) that will inspect each of the samples that is delivered to the COSAC & PTOLEMY ovens before the samples are heated.

ROLIS is a single camera, also with a 1024×1024 CCD detector, with the primary role of surveying the landing site during the descent phase. The camera is fixed and downward pointing with an f/5 (f-ratio) focus adjustable lens with a 57 degree field of view. During descent it is set to infinity and will take images every 5 seconds. Its electronics will compress the data to minimize the total data that must be stored and transmitted to Rosetta. Focus will adjust just prior to touchdown but thereafter, the camera functions in macro mode to spectroscopically survey the comet immediately underneath Philae. Rotation of the Philae body will create a “working circle” for ROLIS.

The multi-role design of ROLIS clearly shows how scientists and engineers worked together to overall reduce weight, volume, and power consumption, and make Philae possible and, together with Rosetta, fit within payload limits of the launch vehicle, power limitations of the solar cells and batteries, limitations of the command and data system and radio transmitters.

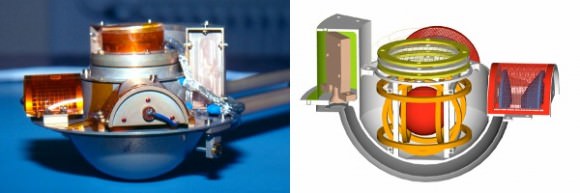

APXS. This is a Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer. This is a near must-have instrument of the space scientist’s Swiss Army Knife. APXS spectrometers have become a common fixture on all Mars Rover missions and Philae’s is an upgraded version of Mars Pathfinder’s. The legacy of the APXS design is the early experiments by Ernest Rutherford and others that led to discovering the structure of the atom and the quantum nature of light and matter.

This instrument has a small source of Alpha particle emission (Curium 244) essential to its operation. The principles of Rutherford Back-scattering of Alpha particles is used to detect the presence of lighter elements such as Hydrogen or Beryllium (those close to an Alpha particle in mass, a Helium nucleus). The mass of such lighter elemental particles will absorb a measurable amount of energy from the Alpha particle during an elastic collision; as happens in Rutherford back-scattering near 180 degrees. However, some Alpha particles are absorbed rather than reflected by the nuclei of the material. Absorption of an Alpha particle causes emission of a proton with a measurable kinetic energy that is also unique to the elemental particle from which it came (in the cometary material); this is used to detect heavier elements such as magnesium or sulfur. Lastly, inner shell electrons in the material of interest can be expelled by Alpha particles. When electrons from outer shells replace these lost electrons, they emit an X-Ray of specific energy (quantum) that is unique to that elementary particle; thus, heavier elements such as Iron or Nickel are detectable. APXS is the embodiment of early 20th Century Particles Physics.

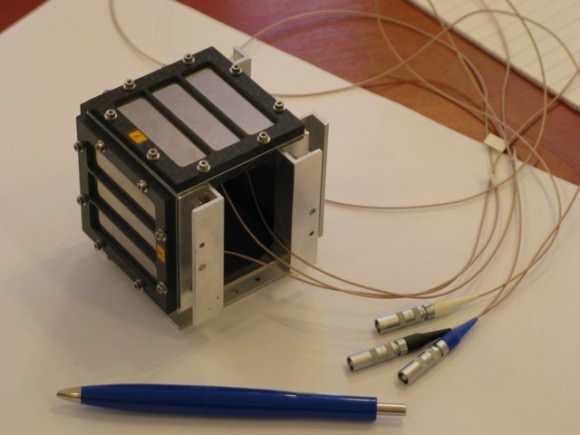

CONSERT. COmet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radio wave Transmission, as the name suggests, will transmit radio waves into the comet’s nucleus. The Rosetta orbiter transmits 90 MHz radio waves and simultaneously Philae stands on the surface to receive with the comet residing between them. Consequently, the time of travel through the comet and the remaining energy of the radio waves is a signature of the material through which it propagated. Many radio transmissions and receptions by CONSERT through a multitude of angles will be required to determine the interior structure of the comet. It is similar to how one might sense the shape of a shadowy object standing in front of you by panning one’s head left and right to watch how the silhouette changes; altogether your brain perceives the shape of the object. With CONSERT data, a complex deconvolution process using computers is necessary. The precision to which the comet’s interior is known improves with more measurements.

MUPUS. Multi-Purpose Sensor for Surface and Subsurface Science is a suite of detectors for measuring the energy balance, thermal and mechanical properties of the comet’s surface and subsurface down to a depth of 30 cm (1 foot). There are three major parts to MUPUS. There is the PEN which is the penetrator tube. PEN is attached to a hammering arm that extends up to 1.2 meters from the body. It deploys with sufficient downward force to penetrate and bury PEN below the surface; multiple hammer strokes are possible. At the tip, or anchor, of PEN (the penetrator tube) is an accelerometer and standard PT100 (Platinum Resistance Thermometer). Together, the anchor sensors will determine the hardness profile at the landing site and the thermal diffusivity at the final depth [ref]. As it penetrates the surfaces, more or less deceleration indicates harder or softer material. The PEN includes an array of 16 thermal detectors along its length to measure subsurface temperatures and thermal conductivity. The PEN also has a heat source to transmit heat to the cometary material and measure its thermal dynamics. With the heat source off, detectors in PEN will monitor the temperature and energy balance of the comet as it approaches the Sun and heats up. The second part is the MUPUS TM, a radiometer atop the PEN which will measure thermal dynamics of the surface. TM consists of four thermopile sensors with optical filters to cover a wavelength range from 6-25 µm.

SD2 Sample Drill and Distribution device will penetrate the surface and subsurface to a depth of 20 cm. Each retrieved sample will be a few cubic millimeters in volume and distributed to 26 ovens mounted on a carousel. The ovens heat the sample which creates a gas that is delivered to the gas chromatographs and mass spectrometers that are COSAC and PTOLEMY. Observations and analysis of APXS and ROLIS data will be used to determine the sampling locations all of which will be on a “working circle” from the rotation of Philae’s body about its Z-axis.

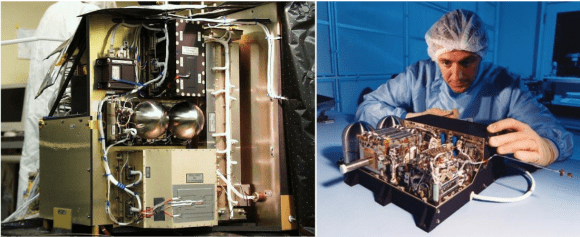

COSAC Cometary Sampling and Composition experiment. The first gas chromatograph (GC) I saw was in a college lab and was being used by the lab manager for forensic tests supporting the local police department. The intent of Philae is nothing less than to perform forensic tests on a comet hundred of million of miles from Earth. Philae is effectively Sherlock Holmes’ spy glass and Sherlock is all the researchers back on Earth. The COSAC gas chromatograph includes a mass spectrometer and will measure the quantities of elements and molecules, particularly complex organic molecules, making up comet material. While that first lab GC I saw was closer to the size of Philae, the two GCs in Philae are about the size of shoe boxes.

PTOLEMY. An Evolved Gas Analyzer [ref], a different type of gas chromatograph. The purpose of Ptolemy is to measure the quantities of specific isotopes to derive the isotopic ratios, for example, 2 parts isotope C12 to one part C13. By definition, isotopes of an element have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. One example is the 3 isotopes of Carbon, C12, C13 and C14; the numbers being the number of neutrons. Some isotopes are stable while others can be unstable – radioactive and decay into stable forms of the same element or into other elements. What is of interest to Ptolemy investigators is the ratio of stable isotopes (natural and not those affected by, or that result from, radioactive decay) for the elements H, C, N, O and S, but particularly Carbon. The ratios will be telltale indicators of where and how comets are created. Until now, spectroscopic measurements of comets to determine isotopic ratios have been from a distance and the accuracy has been inadequate for drawing firm conclusions about the origin of comets and how comets are linked to the creation of planets and the evolution of the Solar Nebula, the birthplace of our planetary system surrounding the Sun, our star. An evolved gas analyzer will heat up a sample (~1000 C) to transform the materials into a gaseous state which a spectrometer can very accurately measure quantities. A similar instrument, TEGA (Thermal Evolved Gas Analyzer) was an instrument on Mars Phoenix lander.

SESAME Surface Electrical Sounding and Acoustic Monitoring Experiment This instrument involves three unique detectors. The first is the SESAME/CASSE, the acoustic detector. Each landing foot of Philae has acoustic emitters and receivers. Each of the legs will take turns transmitting acoustic waves (100 Hertz to KiloHertz range) into the comet which the sensors of the other legs will measure. How that wave is attenuated, that is, weakened and transformed, by the cometary material it passes through, can be used along with other cometary properties gained from Philae instruments, to determine daily and seasonal variations in the comet’s structure to a depth of about 2 meters. Also, in a passive (listening) mode, CASSE will monitor sound waves from creaks, groans inside the comet caused potentially by stresses from Solar heating and venting gases.

Next is the SESAME/PP detector – the Permittivity Probe. Permittivity is the measure of the resistance a material has to electric fields. SESAME/PP will deliver an oscillating (sine wave) electric field into the comet. Philae’s feet carry the receivers – electrodes and AC sine generators to emit the electric field. The resistance of the cometary material to about a 2 meter depth is thus measured providing another essential property of the comet – the permittivity.

The third detector is called SESAME/DIM. This is the comet dust counter. There were several references used to compile these instrument descriptions. For this instrument, there is, what I would call, a beautiful description which I will simply quote here with reference. “The Dust Impact Monitor (DIM) cube on top of the Lander balcony is a dust sensor with three active orthogonal (50 × 16) mm piezo sensors. From the measurement of the transient peak voltage and half contact duration, velocities and radii of impacting dust particles can be calculated. Particles with radii from about 0.5 µm to 3 mm and velocities from 0.025–0.25 m/s can be measured. If the background noise is very high, or the rate and/or the amplitudes of the burst signal are too high, the system automatically switches to the so called Average Continuous mode; i.e., only the average signal will be obtained, giving a measure of the dust flux.” [ref]

ROMAP Rosetta Lander Magnetometer and Plasma detector also includes a third detector, a pressure sensor. Several spacecraft have flown by comets and an intrinsic magnetic field, one created by the comet’s nucleus (the main body) has never been detected. If an intrinsic magnetic field exists, it is likely to be very weak and landing on the surface would be necessary. Finding one would be extraordinary and would turn theories regarding comets on their heads. Low and behold Philae has a fluxgate magnetometer.

The Earth’s magnetic (B) field surrounding us is measured in the 10s of thousands of nano-Teslas (SI unit, billionth of a Tesla). Beyond Earth’s field, the planets, asteroids, and comets are all immersed in the Sun’s magnetic field which, near the Earth, is measured in single digits, 5 to 10 nano-Tesla. Philae’s detector has a range of +/- 2000 nanoTesla; a just in case range but one readily offered by fluxgates. It has a sensitivity of 1/100th of a nanoTesla. So, ESA and Rosetta came prepared. The magnetometer can detect a very minute field if it’s there. Now let’s consider the Plasma detector.

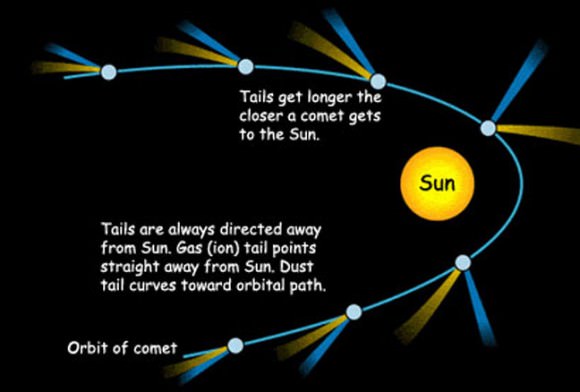

Much of the dynamics of the Universe involves the interaction of plasma – ionized gases (generally missing one or more electrons thus carrying a positive electric charge) with magnetic fields. Comets also involve such interactions and Philae carries a plasma detector to measure the energy, density and direction of electrons and of positively charged ions. Active comets are releasing essentially a neutral gas into space plus small solid (dust) particles. The Sun’s ultraviolet radiation partially ionizes the cometary gas of the comet’s tail, that is, creates a plasma. At some distance from the comet nucleus depending on how hot and dense that plasma is, there is a standoff between the Sun’s magnetic field and the plasma of the tail. The Sun’s B field drapes around the comet’s tail kind of like a white sheet draped over a Halloween trick-or-treater but without eye holes.

So at P67’s surface, Philae’s ROMAP/SPM detector, electrostatic analyzers and a Faraday Cup sensor will measure free electrons and ions in the not so empty space. A “cold” plasma surrounds the comet; SPM will detect ion kinetic energy in the range of 40 to 8000 electron-volts (eV) and electrons from 0.35 eV to 4200 eV. Last but not least, ROMAP includes a pressure sensor which can measure very low pressure – a millionth or a billionth or less than the air pressure we enjoy on Earth. A Penning Vacuum gauge is utilized which ionizes the primarily neutral gas near the surface and measures the current that is generated.

Philae will carry 10 instrument suites to the surface of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko but altogether the ten represent 15 different types of detectors. Some are interdependent, that is, in order to derive certain properties, one needs multiple data sets. Landing Philae on the comet surface will provide the means to measure many properties of a comet for the fist time and others with significantly higher accuracy. Altogether, scientists will come closer to understanding the origins of comets and their contribution to the evolution of the Solar System.