Europa is probably the best place in the Solar System to go searching for life. But before they’re launched, any spacecraft we send will need to be squeaky clean so don’t contaminate the place with our filthy Earth bacteria.

Continue reading “Will We Contaminate Europa?”

Weekly Space Hangout – Oct. 30, 2015: Yoav Landsman and the Enceladus Flyby

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: Yoav Landsman,WSH Crew Member; Principal System Engineer at SpaceIL; member of first GLXP to “hitch a ride.”

Guests:

Pamela Gay (cosmoquest.org / @cosmoquestx / @starstryder)

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @MorganRehnberg )

Paul Sutter (pmsutter.com / @PaulMattSutter)

Dave Dickinson (@astroguyz / www.astroguyz.com)

Alessondra Springmann (@sondy)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – Oct. 30, 2015: Yoav Landsman and the Enceladus Flyby”

Is Jupiter Our Friend Or Enemy?

Like me, you’re probably a little ego-geocentric about the importance of Earth. It’s where you were born, it’s where you keep all your stuff. It’s even where you’re going to die – I know, I know, not you Elon Musk, you’re going to “retire” on Mars, right after you nuke the snot out of it.

For the rest of us, Earth is the place. But in reality, when it comes to planets, this is somebody else’s racket. This is Jupiter’s Solar System, and we all sleep on its couch.

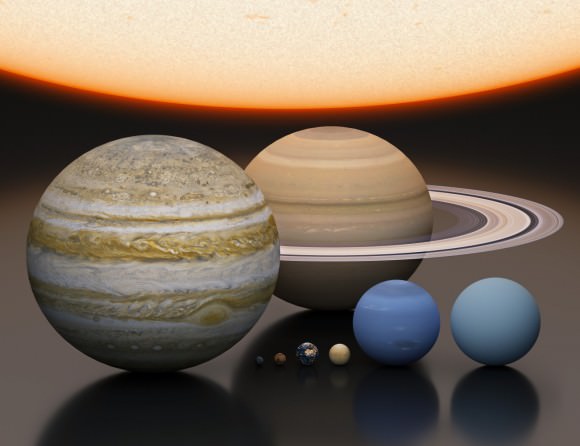

Jupiter accounts for 75% of the mass of the planets of the Solar System, nearly 318 times more massive than Earth, and isn’t just the name of everyone’s favorite secret princess. It’s the 1.9 × 10^27 kilogram gorilla in the room. Whatever Jupiter wants, Jupiter gets. Jupiter hungry? JUPITER HUNGRY.

What Jupiter apparently wants is to throw our stuff around the Solar System. Thanks to its immense gravity, Jupiter yanks material around in the asteroid belt, preventing the poor space rocks from ever forming up into anything larger than Ceres.

Jupiter gobbles up asteroids, comets, and spacecraft, and hurtles others on wayward trajectories. Who knows how much mayhem and destruction Jupiter has gotten into over the course of its 4.5 billion years in the Solar System.

Some scientists think we owe our existence to Jupiter’s protective gravity. It greedily vacuums up dangerous asteroids and comets in the Solar System.

Other scientists totally disagree and think that Jupiter is a bully, perturbing perfectly safe comets and asteroids into dangerous trajectories and flushing earth’s head in the toilet during recess.

Which is it? Is Jupiter our friend and protector, or evil enemy. We’ve already figured out how to dismantle you Jupiter, don’t make us put our plans into action.

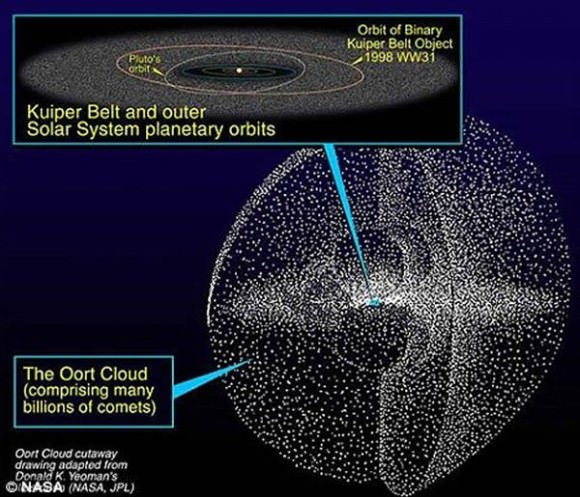

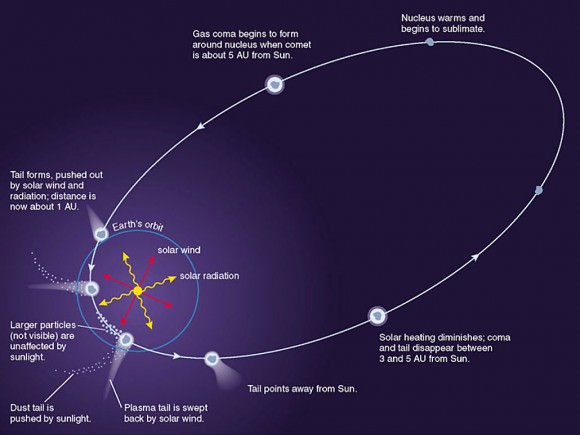

Some of the most dangerous objects in the Solar System are long-period comets. These balls of rock and ice come from the deepest depths of the Oort cloud. Some event nudges these death missiles into trajectories that bring them into the inner Solar System, to shoot past the Sun and maybe, just maybe, smash into a planet and kill 99.99999% of the life on it.

There’s a pretty good chance some of the biggest extinctions in the history of the Earth were caused by impacts by long period comets.

As these comets make their way through the Solar System, they interact with Jupiter’s massive gravity, and get pushed this way and that. As we saw with Comet Shoemaker-Levy, some just get consumed entirely, like a tasty ice-rock sandwich.

The theory goes that Jupiter pushes these dangerous comets out of their murder orbits so they don’t smash into Earth and kill us all.

But a competing theory says that Jupiter actually diverts comets that would have completely missed our planet into deadly, Earth-killing trajectories.

Will the Sailor Scouts provide us any clues? Who can say?

Here’s friend of the show, Dr. Kevin Grazier, a planetary scientist and scientific advisor for many of your favorite sci-fi TV shows and movies.

… [ see video for Interview with Dr. Grazier about Jupiter]

So which is it? Is Jupiter our friend or enemy? We’ll need to run more simulations and figure this out with more accuracy. And until then, it’s probably best if we just tremble in fear and worship Jupiter as a dark and capricious god until the evidence proves otherwise. It’s what Pascal would wager.

What are some other theories you’ve heard about and you’d like us to dig in further? Make some suggestions in the comments below.

Thanks for watching! Click subscribe, never miss an episode.

If you’re into other facts about our Solar system here’s a link to our Solar system playlist. Thanks to Ben Johnson and Tal Ghengis, and the members of the Guide to Space community who keep these shows rolling. Love space science? Want to see episodes before anyone else? Get extras, contests, and shenanigans with Jay, myself and the rest of the team. Get in on the action. Click here.

Solar System Guide

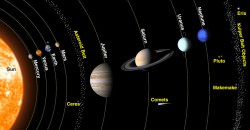

The Universe is a very big place, and we occupy a very small corner of it. Known as the Solar System, our stomping grounds are not only a tiny fraction of the Universe as we know it, but is also a very small part of our galactic neighborhood (aka. the Milky Way Galaxy). When it comes right down to it, our world is just a drop of water in an endless cosmic sea.

Nevertheless, the Solar System is still a very big place, and one which is filled with its fair share of mysteries. And in truth, it was only within the relatively recent past that we began to understand its true extent. And when it comes to exploring it, we’ve really only begun to scratch the surface.

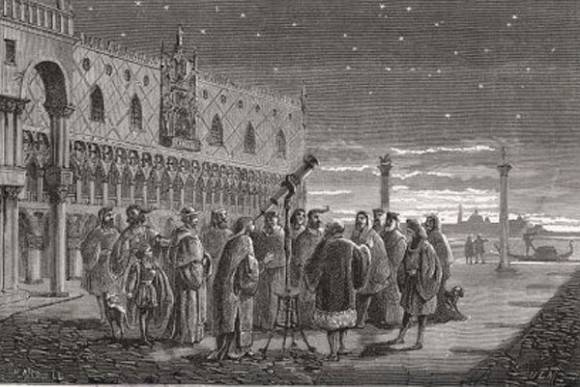

Discovery:

With very few exceptions, few people or civilizations before the era of modern astronomy recognized the Solar System for what it was. In fact, the vast majority of astronomical systems posited that the Earth was a stationary object and that all known celestial objects revolved around it. In addition, they viewed it as being fundamentally different from other stellar objects, which they held to be ethereal or divine in nature.

Although there were some Greek, Arab and Asian astronomers during Antiquity and the Medieval period who believed that the universe was heliocentric in nature (i.e. that the Earth and other bodies revolved around the Sun) it was not until Nicolaus Copernicus developed his mathematically predictive model of a heliocentric system in the 16th century that it began to become widespread.

During the 17th-century, scientists like Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton developed an understanding of physics which led to the gradual acceptance that the Earth revolves round the Sun. The development of theories like gravity also led to the realization that the other planets are governed by the same physical laws as Earth.

The widespread use of the telescope also led to a revolution in astronomy. After Galileo discovered the moons of Jupiter in 1610, Christian Huygens would go on to discover that Saturn also had moons in 1655. In time, new planets would also be discovered (such as Uranus and Neptune), as well as comets (such as Halley’s Comet) and the Asteroids Belt.

By the 19th century, three observations made by three separate astronomers determined the true nature of the Solar System and its place the universe. The first was made in 1839 by German astronomer Friedrich Bessel, who successfully measured an apparent shift in the position of a star created by the Earth’s motion around the Sun (aka. stellar parallax). This not only confirmed the heliocentric model beyond a doubt, but revealed the vast distance between the Sun and the stars.

In 1859, Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff (a German chemist and physicist) used the newly invented spectroscope to examined the spectral signature of the Sun. They discovered that it was composed of the same elements as existed on Earth, thus proving that Earth and the heavens were composed of the same elements.

Then, Father Angelo Secchi – an Italian astronomer and director at the Pontifical Gregorian University – compared the spectral signature of the Sun with those of other stars, and found them to be virtually identical. This demonstrated conclusively that our Sun was composed of the same materials as every other star in the universe.

Further apparent discrepancies in the orbits of the outer planets led American astronomer Percival Lowell to conclude that yet another planet, which he referred to as “Planet X“, must lie beyond Neptune. After his death, his Lowell Observatory conducted a search that ultimately led to Clyde Tombaugh’s discovery of Pluto in 1930.

Also in 1992, astronomers David C. Jewitt of the University of Hawaii and Jane Luu of the MIT discovered the Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO) known as (15760) 1992 QB1. This would prove to be the first of a new population, known as the Kuiper Belt, which had already been predicted by astronomers to exist at the edge of the Solar System.

Further investigation of the Kuiper Belt by the turn of the century would lead to additional discoveries. The discovery of Eris and other “plutoids” by Mike Brown, Chad Trujillo, David Rabinowitz and other astronomers would lead to the Great Planet Debate – where IAU policy and the convention for designating planets would be contested.

Structure and Composition:

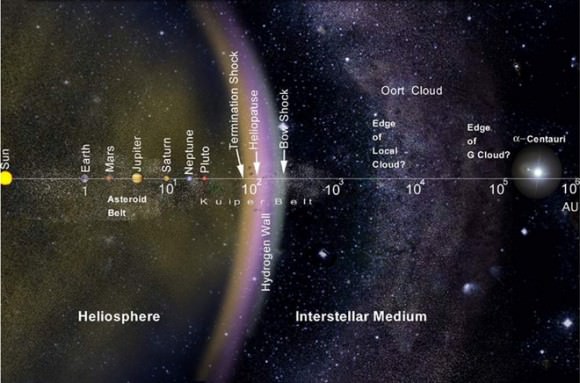

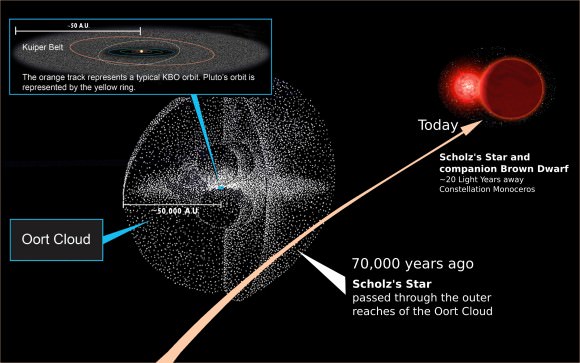

At the core of the Solar System lies the Sun (a G2 main-sequence star) which is then surrounded by four terrestrial planets (the Inner Planets), the main Asteroid Belt, four gas giants (the Outer Planets), a massive field of small bodies that extends from 30 AU to 50 AU from the Sun (the Kuiper Belt). The system is then surrounded a spherical cloud of icy planetesimals (the Oort Cloud) that is believed to extend to a distance of 100,000 AU from the Sun into the Interstellar Medium.

The Sun contains 99.86% of the system’s known mass, and its gravity dominates the entire system. Most large objects in orbit around the Sun lie near the plane of Earth’s orbit (the ecliptic) and most planets and bodies rotate around it in the same direction (counter-clockwise when viewed from above Earth’s north pole). The planets are very close to the ecliptic, whereas comets and Kuiper belt objects are frequently at greater angles to it.

It’s four largest orbiting bodies (the gas giants) account for 99% of the remaining mass, with Jupiter and Saturn together comprising more than 90%. The remaining objects of the Solar System (including the four terrestrial planets, the dwarf planets, moons, asteroids, and comets) together comprise less than 0.002% of the Solar System’s total mass.

Astronomers sometimes informally divide this structure into separate regions. First, there is the Inner Solar System, which includes the four terrestrial planets and the Asteroid Belt. Beyond this, there’s the outer Solar System that includes the four gas giant planets. Meanwhile, there’s the outermost parts of the Solar System are considered a distinct region consisting of the objects beyond Neptune (i.e. Trans-Neptunian Objects).

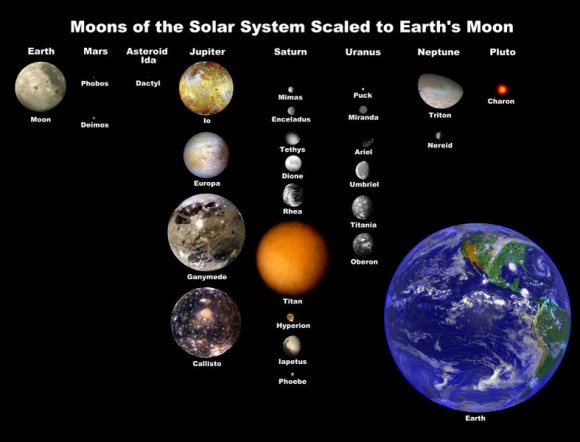

Most of the planets in the Solar System possess secondary systems of their own, being orbited by planetary objects called natural satellites (or moons). In the case of the four giant planets, there are also planetary rings – thin bands of tiny particles that orbit them in unison. Most of the largest natural satellites are in synchronous rotation, with one face permanently turned toward their parent.

The Sun, which comprises nearly all the matter in the Solar System, is composed of roughly 98% hydrogen and helium. The terrestrial planets of the Inner Solar System are composed primarily of silicate rock, iron and nickel. Beyond the Asteroid Belt, planets are composed mainly of gases (such as hydrogen, helium) and ices – like water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide.

Objects farther from the Sun are composed largely of materials with lower melting points. Icy substances comprise the majority of the satellites of the giant planets, as well as most of Uranus and Neptune (hence why they are sometimes referred to as “ice giants”) and the numerous small objects that lie beyond Neptune’s orbit.

Together, gases and ices are referred to as volatiles. The boundary in the Solar System beyond which those volatile substances could condense is known as the frost line, which lies roughly 5 AU from the Sun. Within the Kuiper Belt, objects and planetesimals are composed mainly of these materials and rock.

Formation and Evolution:

The Solar System formed 4.568 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a region within a large molecular cloud composed of hydrogen, helium, and small amounts of heavier elements fused by previous generations of stars. As the region that would become the Solar System (known as the pre-solar nebula) collapsed, conservation of angular momentum caused it to rotate faster.

The center, where most of the mass collected, became increasingly hotter than the surrounding disc. As the contracting nebula rotated faster, it began to flatten into a protoplanetary disc with a hot, dense protostar at the center. The planets formed by accretion from this disc, in which dust and gas gravitated together and coalesced to form ever larger bodies.

Due to their higher boiling points, only metals and silicates could exist in solid form closer to the Sun, and these would eventually form the terrestrial planets of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Because metallic elements only comprised a very small fraction of the solar nebula, the terrestrial planets could not grow very large.

In contrast, the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) formed beyond the point between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where material is cool enough for volatile icy compounds to remain solid (i.e. the frost line).

The ices that formed these planets were more plentiful than the metals and silicates that formed the terrestrial inner planets, allowing them to grow massive enough to capture large atmospheres of hydrogen and helium. Leftover debris that never became planets congregated in regions such as the asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, and Oort cloud.

Within 50 million years, the pressure and density of hydrogen in the center of the protostar became great enough for it to begin thermonuclear fusion. The temperature, reaction rate, pressure, and density increased until hydrostatic equilibrium was achieved.

At this point, the Sun became a main-sequence star. Solar wind from the Sun created the heliosphere and swept away the remaining gas and dust from the protoplanetary disc into interstellar space, ending the planetary formation process.

The Solar System will remain roughly as we know it today until the hydrogen in the core of the Sun has been entirely converted to helium. This will occur roughly 5 billion years from now and mark the end of the Sun’s main-sequence life. At this time, the core of the Sun will collapse, and the energy output will be much greater than at present.

The outer layers of the Sun will expand to roughly 260 times its current diameter, and the Sun will become a red giant. The expanding Sun is expected to vaporize Mercury and Venus and render Earth uninhabitable as the habitable zone moves out to the orbit of Mars. Eventually, the core will be hot enough for helium fusion and the Sun will burn helium for a time, after which nuclear reactions in the core will start to dwindle.

At this point, the Sun’s outer layers will move away into space, leaving a white dwarf – an extraordinarily dense object that will have half the original mass of the Sun, but will be the size of Earth. The ejected outer layers will form what is known as a planetary nebula, returning some of the material that formed the Sun to the interstellar medium.

Inner Solar System:

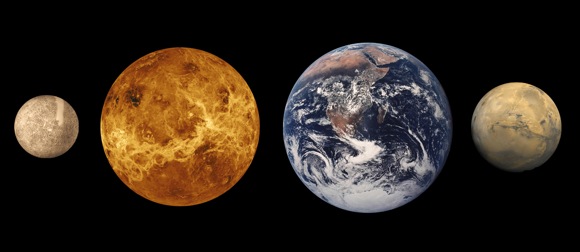

In the inner Solar System, we find the “Inner Planets” – Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars – which are so named because they orbit closest to the Sun. In addition to their proximity, these planets have a number of key differences that set them apart from planets elsewhere in the Solar System.

For starters, the inner planets are rocky and terrestrial, composed mostly of silicates and metals, whereas the outer planets are gas giants. The inner planets are also much more closely spaced than their outer Solar System counterparts. In fact, the radius of the entire region is less than the distance between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn.

Generally, inner planets are smaller and denser than their counterparts, and have few to no moons or rings circling them. The outer planets, meanwhile, often have dozens of satellites and rings composed of particles of ice and rock.

The terrestrial inner planets are composed largely of refractory minerals such as the silicates, which form their crusts and mantles, and metals such as iron and nickel which form their cores. Three of the four inner planets (Venus, Earth and Mars) have atmospheres substantial enough to generate weather. All of them have impact craters and tectonic surface features as well, such as rift valleys and volcanoes.

Of the inner planets, Mercury is the closest to our Sun and the smallest of the terrestrial planets. Its magnetic field is only about 1% that of Earth’s, and it’s very thin atmosphere means that it is hot during the day (up to 430°C) and freezing at night (as low as -187 °C) because the atmosphere can neither keep heat in or out. It has no moons of its own and is comprised mostly of iron and nickel. Mercury is one of the densest planets in the Solar System.

Venus, which is about the same size as Earth, has a thick toxic atmosphere that traps heat, making it the hottest planet in the Solar System. This atmosphere is composed of 96% carbon dioxide, along with nitrogen and a few other gases. Dense clouds within Venus’ atmosphere are composed of sulphuric acid and other corrosive compounds, with very little water. Much of Venus’ surface is marked with volcanoes and deep canyons – the biggest of which is over 6400 km (4,000 mi) long.

Earth is the third inner planet and the one we know best. Of the four terrestrial planets, Earth is the largest, and the only one that currently has liquid water, which is necessary for life as we know it. Earth’s atmosphere protects the planet from dangerous radiation and helps keep valuable sunlight and warmth in, which is also essential for life to survive.

Like the other terrestrial planets, Earth has a rocky surface with mountains and canyons, and a heavy metal core. Earth’s atmosphere contains water vapor, which helps to moderate daily temperatures. Like Mercury, the Earth has an internal magnetic field. And our Moon, the only one we have, is comprised of a mixture of various rocks and minerals.

Mars is the fourth and final inner planet, and is also known as the “Red Planet” due to the oxidization of iron-rich materials that form the planet’s surface. Mars also has some of the most interesting terrain features of any of the terrestrial planets. These include the largest mountain in the Solar System (Olympus Mons) which rises some 21,229 m (69,649 ft) above the surface, and a giant canyon called Valles Marineris – which is 4000 km (2500 mi) long and reaches depths of up to 7 km (4 mi).

Much of Mars’ surface is very old and filled with craters, but there are geologically newer areas of the planet as well. At the Martian poles are polar ice caps that shrink in size during the Martian spring and summer. Mars is less dense than Earth and has a smaller magnetic field, which is indicative of a solid core, rather than a liquid one.

Mars’ thin atmosphere has led some astronomers to believe that the surface water that once existed there might have actually taken liquid form, but has since evaporated into space. The planet has two small moons called Phobos and Deimos.

Outer Solar System:

The outer planets (sometimes called Jovian planets or gas giants) are huge planets swaddled in gas that have rings and plenty of moons. Despite their size, only two of them are visible without telescopes: Jupiter and Saturn. Uranus and Neptune were the first planets discovered since antiquity, and showed astronomers that the solar system was bigger than previously thought.

Jupiter is the largest planet in our Solar System and spins very rapidly (10 Earth hours) relative to its orbit of the sun (12 Earth years). Its thick atmosphere is mostly made up of hydrogen and helium, perhaps surrounding a terrestrial core that is about Earth’s size. The planet has dozens of moons, some faint rings and a Great Red Spot – a raging storm that has happening for the past 400 years at least.

Saturn is best known for its prominent ring system – seven known rings with well-defined divisions and gaps between them. How the rings got there is one subject under investigation. It also has dozens of moons. Its atmosphere is mostly hydrogen and helium, and it also rotates quickly (10.7 Earth hours) relative to its time to circle the Sun (29 Earth years).

Uranus was first discovered by William Herschel in 1781. The planet’s day takes about 17 Earth hours and one orbit around the Sun takes 84 Earth years. Its mass contains water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen and helium surrounding a rocky core. It has dozens of moons and a faint ring system. The only spacecraft to visit this planet was the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1986.

Neptune is a distant planet that contains water, ammmonia, methane, hydrogen and helium and a possible Earth-sized core. It has more than a dozen moons and six rings. NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft also visited this planet and its system by 1989 during its transit of the outer Solar System.

Trans-Neptunian Region:

There have been more than a thousand objects discovered in the Kuiper Belt, and it’s theorized that there are as many as 100,000 objects larger than 100 km in diameter. Given to their small size and extreme distance from Earth, the chemical makeup of KBOs is very difficult to determine.

However, spectrographic studies conducted of the region since its discovery have generally indicated that its members are primarily composed of ices: a mixture of light hydrocarbons (such as methane), ammonia, and water ice – a composition they share with comets. Initial studies also confirmed a broad range of colors among KBOs, ranging from neutral grey to deep red.

This suggests that their surfaces are composed of a wide range of compounds, from dirty ices to hydrocarbons. In 1996, Robert H. Brown et al. obtained spectroscopic data on the KBO 1993 SC, revealing its surface composition to be markedly similar to that of Pluto (as well as Neptune’s moon Triton) in that it possessed large amounts of methane ice.

Water ice has been detected in several KBOs, including 1996 TO66, 38628 Huya and 20000 Varuna. In 2004, Mike Brown et al. determined the existence of crystalline water ice and ammonia hydrate on one of the largest known KBOs, 50000 Quaoar. Both of these substances would have been destroyed over the age of the Solar System, suggesting that Quaoar had been recently resurfaced, either by internal tectonic activity or by meteorite impacts.

Keeping Pluto company out in the Kuiper belt are many other objects worthy of mention. Quaoar, Makemake, Haumea, Orcus and Eris are all large icy bodies in the Belt and several of them even have moons of their own. These are all tremendously far away, and yet, very much within reach.

Oort Cloud and Farthest Regions:

The Oort Cloud is thought to extend from between 2,000 and 5,000 AU (0.03 and 0.08 ly) to as far as 50,000 AU (0.79 ly) from the Sun, though some estimates place the outer edge as far as 100,000 and 200,000 AU (1.58 and 3.16 ly). The Cloud is thought to be comprised of two regions – a spherical outer Oort Cloud of 20,000 – 50,000 AU (0.32 – 0.79 ly), and disc-shaped inner Oort (or Hills) Cloud of 2,000 – 20,000 AU (0.03 – 0.32 ly).

The outer Oort cloud may have trillions of objects larger than 1 km (0.62 mi), and billions that measure 20 kilometers (12 mi) in diameter. Its total mass is not known, but – assuming that Halley’s Comet is a typical representation of outer Oort Cloud objects – it has the combined mass of roughly 3×1025 kilograms (6.6×1025 pounds), or five Earths.

Based on the analyses of past comets, the vast majority of Oort Cloud objects are composed of icy volatiles – such as water, methane, ethane, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and ammonia. The appearance of asteroids thought to be originating from the Oort Cloud has also prompted theoretical research that suggests that the population consists of 1-2% asteroids.

Earlier estimates placed its mass up to 380 Earth masses, but improved knowledge of the size distribution of long-period comets has led to lower estimates. The mass of the inner Oort Cloud, meanwhile, has yet to be characterized. The contents of both Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud are known as Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), because the objects of both regions have orbits that that are further from the Sun than Neptune’s orbit.

Exploration:

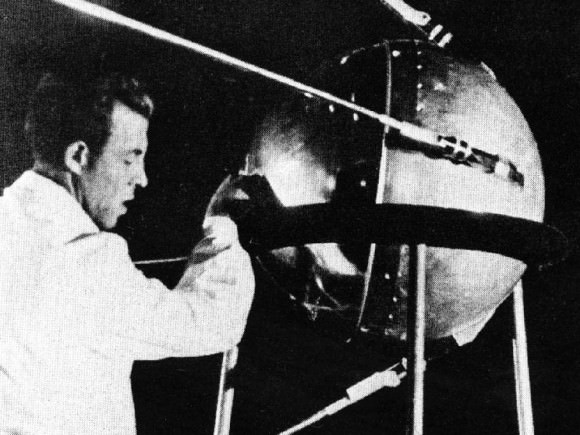

Our knowledge of the Solar System also benefited immensely from the advent of robotic spacecraft, satellites, and robotic landers. Beginning in the mid-20th century, in what was known as “The Space Age“, manned and robotic spacecraft began exploring planets, asteroids and comets in the Inner and Outer Solar System.

All planets in the Solar System have now been visited to varying degrees by spacecraft launched from Earth. Through these unmanned missions, humans have been able to get close-up photographs of all the planets. In the case of landers and rovers, tests have been performed on the soils and atmospheres of some.

The first artificial object sent into space was the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1, which was launched in space in 1957, successfully orbited the Earth for months, and collected information on the density of the upper atmosphere and the ionosphere. The American probe Explorer 6, launched in 1959, was the first satellite to capture images of the Earth from space.

Robotic spacecraft conducting flybys also revealed considerable information about the planet’s atmospheres, geological and surface features. The first successful probe to fly by another planet was the Soviet Luna 1 probe, which sped past the Moon in 1959. The Mariner program resulted in multiple successful planetary flybys, consisting of the Mariner 2 mission past Venus in 1962, the Mariner 4 mission past Mars in 1965, and the Mariner 10 mission past Mercury in 1974.

By the 1970’s, probes were being dispatched to the outer planets as well, beginning with the Pioneer 10 mission which flew past Jupiter in 1973 and the Pioneer 11 visit to Saturn in 1979. The Voyager probes performed a grand tour of the outer planets following their launch in 1977, with both probes passing Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980-1981. Voyager 2 then went on to make close approaches to Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

Launched on January 19th, 2006, the New Horizons probe is the first man-made spacecraft to explore the Kuiper Belt. This unmanned mission flew by Pluto in July 2015. Should it prove feasible, the mission will also be extended to observe a number of other Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) in the coming years.

Orbiters, rovers, and landers began being deployed to other planets in the Solar System by the 1960’s. The first was the Soviet Luna 10 satellite, which was sent into lunar orbit in 1966. This was followed in 1971 with the deployment of the Mariner 9 space probe, which orbited Mars, and the Soviet Venera 9 which orbited Venus in 1975.

The Galileo probe became the first artificial satellite to orbit an outer planet when it reached Jupiter in 1995, followed by the Cassini–Huygens probe orbiting Saturn in 2004. Mercury and Vesta were explored by 2011 by the MESSENGER and Dawn probes, respectively, with Dawn establishing orbit around the asteroid/dwarf planet Ceres in 2015.

The first probe to land on another Solar System body was the Soviet Luna 2 probe, which impacted the Moon in 1959. Since then, probes have landed on or impacted on the surfaces of Venus in 1966 (Venera 3), Mars in 1971 (Mars 3 and Viking 1 in 1976), the asteroid 433 Eros in 2001 (NEAR Shoemaker), and Saturn’s moon Titan (Huygens) and the comet Tempel 1 (Deep Impact) in 2005.

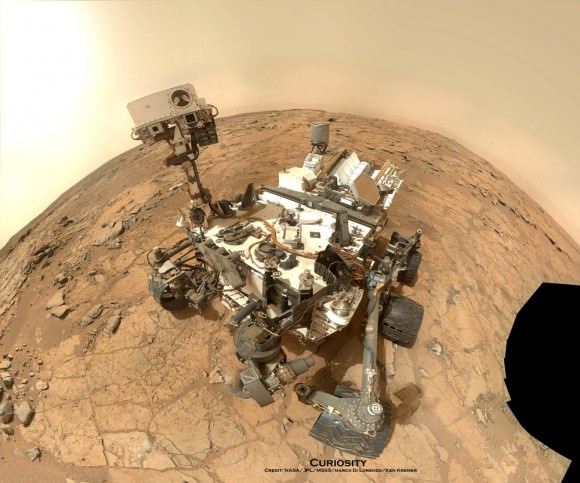

To date, only two worlds in the Solar System, the Moon and Mars, have been visited by mobile rovers. The first robotic rover to land on another planet was the Soviet Lunokhod 1, which landed on the Moon in 1970. The first to visit another planet was Sojourner, which traveled 500 meters across the surface of Mars in 1997, followed by Spirit (2004), Opportunity (2004), and Curiosity (2012).

Manned missions into space began in earnest in the 1950’s, and was a major focal point for both the United States and Soviet Union during the “Space Race“. For the Soviets, this took the form of the Vostok program, which involved sending manned space capsules into orbit.

The first mission – Vostok 1 – took place on April 12th, 1961, and was piloted by Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin (the first human being to go into space). On June 6th, 1963, the Soviets also sent the first woman – Valentina Tereshvoka – into space as part of the Vostok 6 mission.

In the US, Project Mercury was initiated with the same goal of placing a crewed capsule into orbit. On May 5th, 1961, astronaut Alan Shepard went into space aboard the Freedom 7 mission and became the first American (and second human) to go into space.

After the Vostok and Mercury programs were completed, the focus of both nations and space programs shifted towards the development of two and three-person spacecraft, as well as the development of long-duration spaceflights and extra-vehicular activity (EVA).

This took the form of the Voshkod and Gemini programs in the Soviet Union and US, respectively. For the Soviets, this involved developing a two to three-person capsule, whereas the Gemini program focused on developing the support and expertise needed for an eventual manned mission to the Moon.

These latter efforts culminated on July 21st, 1969 with the Apollo 11 mission, when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk on the Moon. As part of the Apollo program, five more Moon landings would take place through 1972, and the program itself resulted in many scientific packages being deployed on the Lunar surface, and samples of moon rocks being returned to Earth.

After the Moon Landing took place, the focus of the US and Soviet space programs then began to shift to the development of space stations and reusable spacecraft. For the Soviets, this resulted in the first crewed orbital space stations dedicated to scientific research and military reconnaissance – known as the Salyut and Almaz space stations.

The first orbital space station to host more than one crew was NASA’s Skylab, which successfully held three crews from 1973 to 1974. The first true human settlement in space was the Soviet space station Mir, which was continuously occupied for close to ten years, from 1989 to 1999. It was decommissioned in 2001, and its successor, the International Space Station, has maintained a continuous human presence in space since then.

The United States’ Space Shuttle, which debuted in 1981, became the only reusable spacecraft to successfully make multiple orbital flights. The five shuttles that were built (Atlantis, Endeavour, Discovery, Challenger, Columbia and Enterprise) flew a total of 121 missions before being decommissioned in 2011.

During their history of service, two of the craft were destroyed in accidents. These included the Space Shuttle Challenger – which exploded upon take-off on Jan. 28th, 1986 – and the Space Shuttle Columbia which disintegrated during re-entry on Feb. 1st, 2003.

In 2004, then-U.S. President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, which called for a replacement for the aging Shuttle, a return to the Moon and, ultimately, a manned mission to Mars. These goals have since been maintained by the Obama administration, and now include plans for an Asteroid Redirect mission, where a robotic craft will tow an asteroid closer to Earth so a manned mission can be mounted to it.

All the information gained from manned and robotic missions about the geological phenomena of other planets – such as mountains and craters – as well as their seasonal, meteorological phenomena (i.e. clouds, dust storms and ice caps) have led to the realization that other planets experience much the same phenomena as Earth. In addition, it has also helped scientists to learn much about the history of the Solar System and its formation.

As our exploration of the Inner and Outer Solar System has improved and expanded, our conventions for categorizing planets has also changed. Our current model of the Solar System includes eight planets (four terrestrial, four gas giants), four dwarf planets, and a growing number of Trans-Neptunian Objects that have yet to be designated. It also contains and is surrounded by countless asteroids and planetesimals.

Given its sheer size, composition and complexity, researching our Solar System in full detail would take an entire lifetime. Obviously, no one has that kind of time to dedicate to the topic, so we have decided to compile the many articles we have about it here on Universe Today in one simple page of links for your convenience.

There are thousands of facts about the solar system in the links below. Enjoy your research.

The Solar System:

- Interesting Facts About the Solar System

- Our Solar System

- What is the Solar System?

- How Big is the Solar System?

- Diameter of the Solar System

- Solar System Orbits

- How Old is the Solar System?

- Stars and Planets

- All About Planets

- Inner Solar System

- Beyond the Solar System

- Solar System, Galaxy, Universe

- Diagram of the Solar System

- New Solar System

- Solar System Order

- Oort Cloud

- Interplanetary Space

- Plane of the Ecliptic

- Planetesimals

- Deep Space

- Protoplanets

- Planetoid

- Nemesis

Theories about the Solar System:

- Formation of the Solar System

- How Was the Solar System Formed?

- Origin of the Solar System

- Solar Nebula

- Solar Disruption Theory

- Solar Nebula Theory

- Geocentric Theory

- Geocentric Model

- Heliocentric Model

- Difference Between Geocentric and Heliocentric

Moons:

Anything EXTREME!:

- How Many Stars are in the Solar System?

- Largest Volcano in the Solar System

- What is the Largest Moon in the Solar System?

- What is the Smallest Moon in the Solar System?

- Largest in the Solar System

Solar System Stuffs:

More Evidence That Comets May Have Brought Life to Earth

The idea of panspermia — that life on Earth originated from comets or asteroids bombarding our planet — is not new. But new research may have given the theory a boost. Scientists from Japan say their experiments show that early comet impacts could have caused amino acids to change into peptides, becoming the first building blocks of life. Not only would this help explain the genesis of life on Earth, but it could also have implications for life on other worlds.

Dr. Haruna Sugahara, from the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology in Yokahama, and Dr. Koichi Mimura, from Nagoya University said they conducted “shock experiments on frozen mixtures of amino acid, water ice and silicate (forsterite) at cryogenic condition (77 K),” according to their paper. “In the experiments, the frozen amino acid mixture was sealed into a capsule … a vertical propellant gun was used to [simulate] impact shock.”

They analyzed the post-impact mixture with gas chromatography, and found that some of the amino acids had joined into short peptides of up to 3 units long (tripeptides).

Based on the experimental data, the researchers were able to estimate that the amount of peptides produced would be around the same as had been thought to be produced by normal terrestrial processes (such as lighting storms or hydration and dehydration cycles).

The earliest known fossils on Earth are from about 3.5 billion years ago and there is evidence that biological activity took place even earlier. But there’s evidence that early Earth had little water and carbon-based molecules on the Earth’s surface, so how could these building blocks of life delivered to the Earth’s surface so quickly? This was also about the time of the Late Heavy Bombardment, and so the obvious answer could be the collision of comets and asteroids with the Earth, since these objects contain abundant supplies of both water and carbon-based molecules.

Space missions to comets are helping to confirm this possibility. The 2004 Stardust mission found the amino acid when it collected particles from Comet Wild 2. When NASA’s Deep Impact spacecraft crashed into Comet Tempel 1 in 2005, it discovered a mixture of organic and clay particles inside the comet. One theory about the origins of life is that clay particles act as a catalyst, allowing simple organic molecules to get arranged into more and more complex structures.

The news from the current Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko also indicates that comets are a rich source of materials, and more discoveries are likely to be forthcoming from that mission.

“Two key parts to this story are how complex molecules are initially generated on comets and then how they survive/evolve when the comet hits a planet like the Earth,” said Professor Mark Burchell from the University of Kent in the UK, commenting on the new research from Japan. “Both of these steps can involve shocks which deliver energy to the icy body… building on earlier work, Dr. Sugahara and Dr. Mimura have shown how amino acids on icy bodies can be turned into short peptide sequences, another key step along the path to life.”

“Comet impacts are normally associated with mass extinction on Earth, but this works shows that they probably helped kick-start the whole process of life in the first place,” said Sugahara. “The production of short peptides is the key step in the chemical evolution of complex molecules. Once the process is kick-started, then much less energy is needed to make longer chain peptides in a terrestrial, aquatic environment.”

The scientists also indicated that similar “kickstarting” could have happened in other places in our Solar System, such as on the icy moons Europa and Enceladus, as they likely underwent a similar comet bombardment.

Sugahara and Mimura presented their findings at the Goldschmidt geochemistry conference in Prague, going on this week.

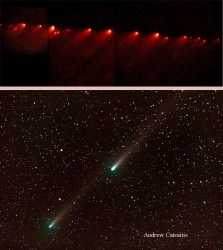

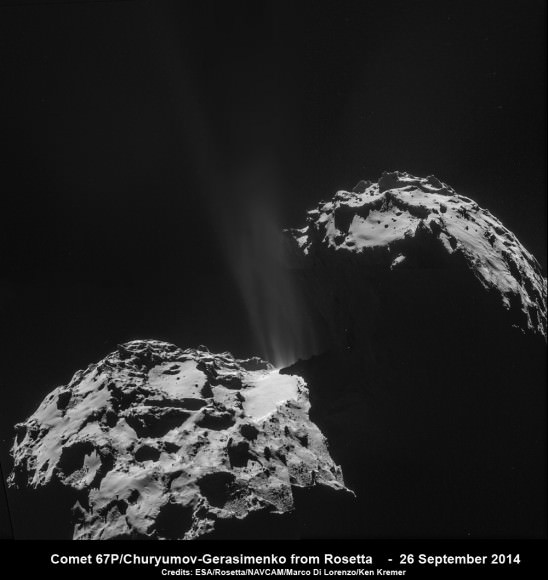

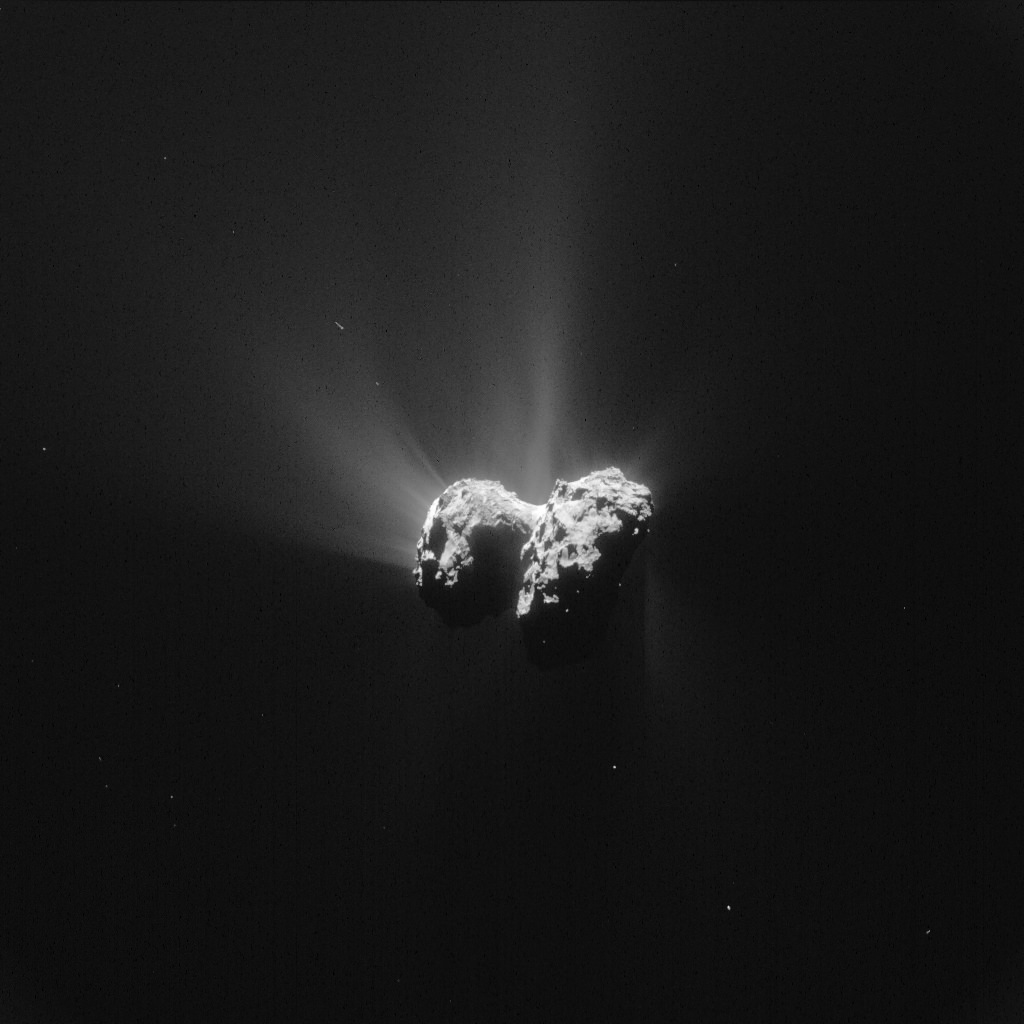

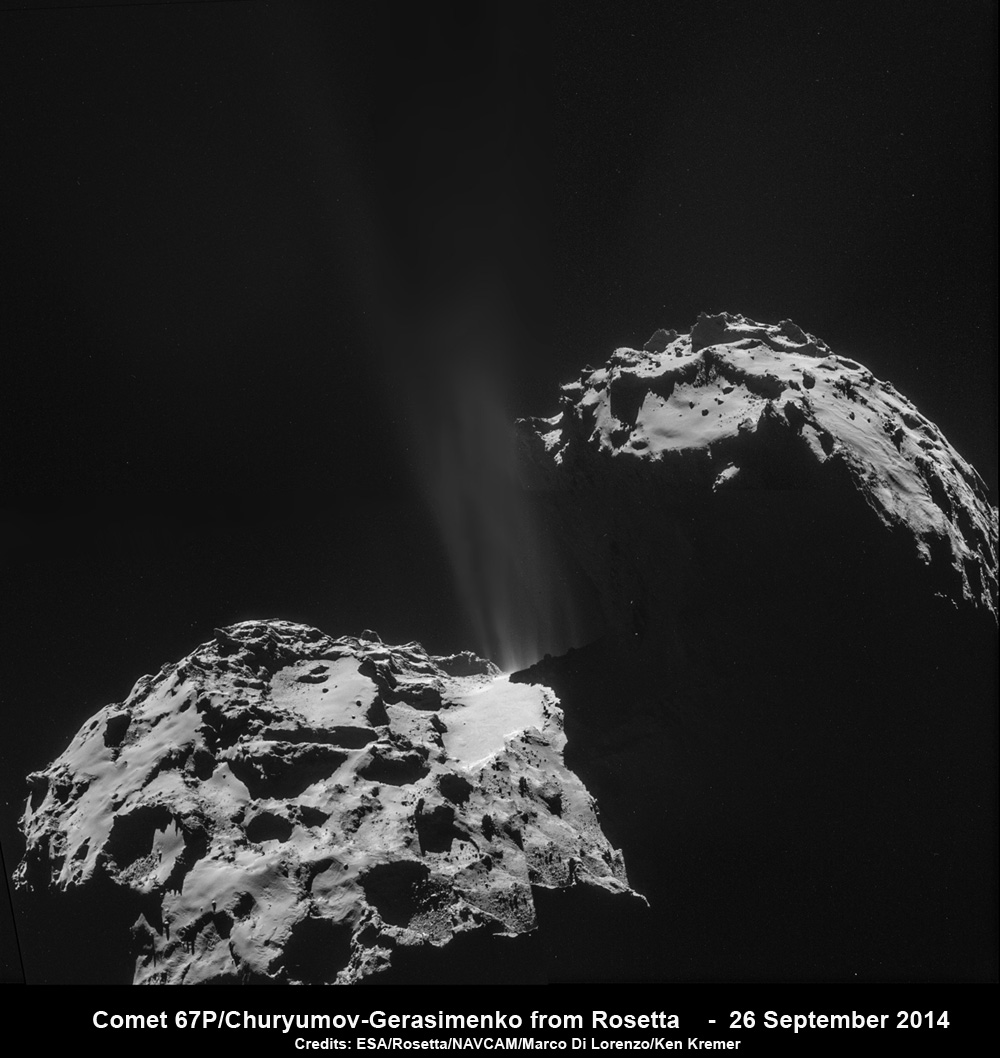

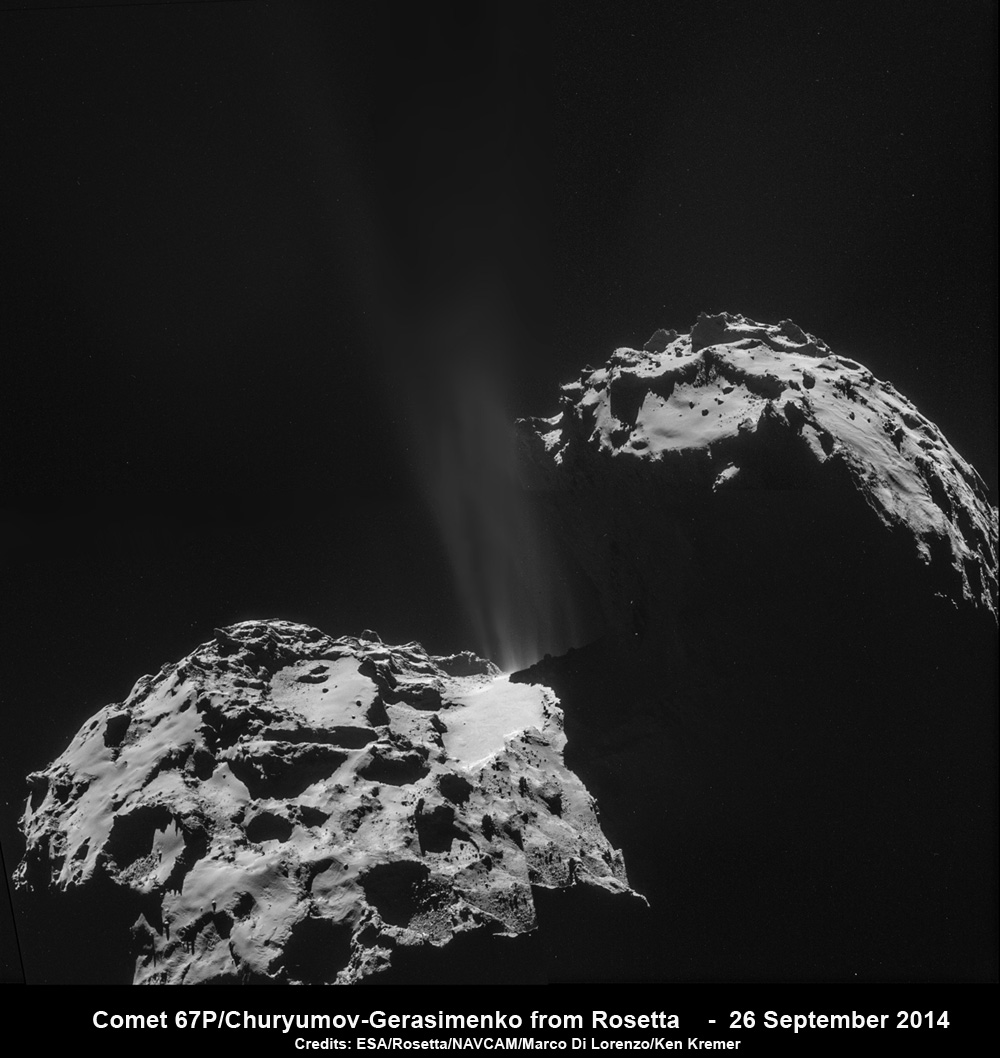

Spectacular Celestial Fireworks Commemorate Perihelion Passage of Rosetta’s Comet

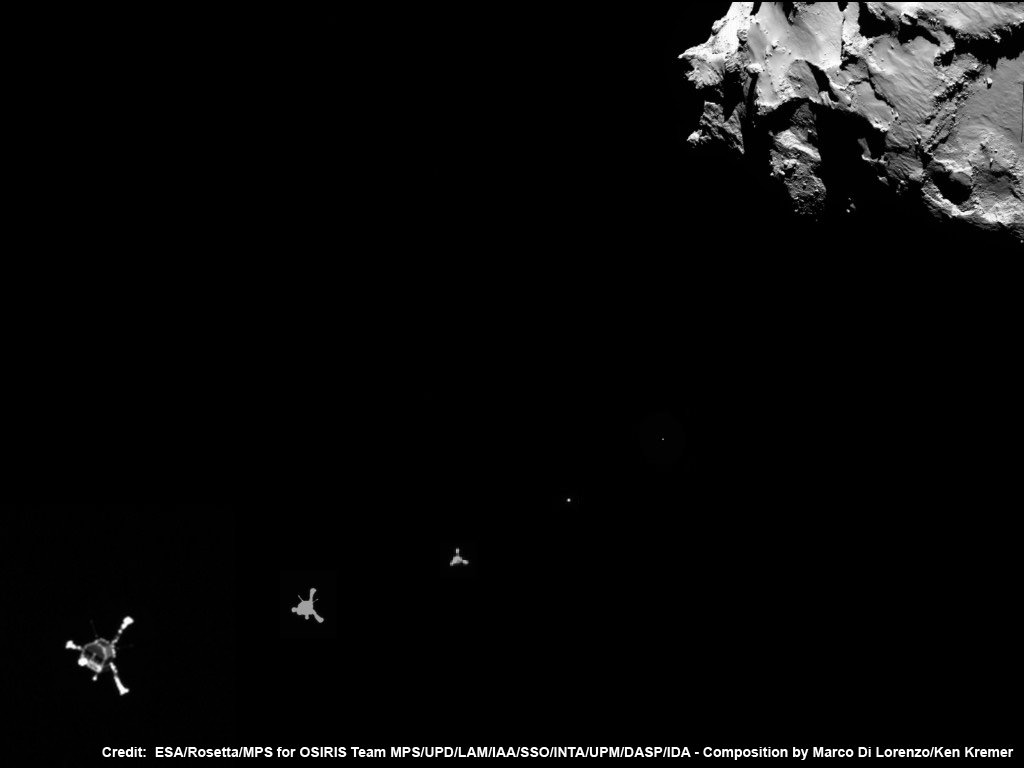

Sequence of OSIRIS narrow-angle camera images from 12 August 2015, just a few hours before the comet reached perihelion. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

See hi res images below[/caption]

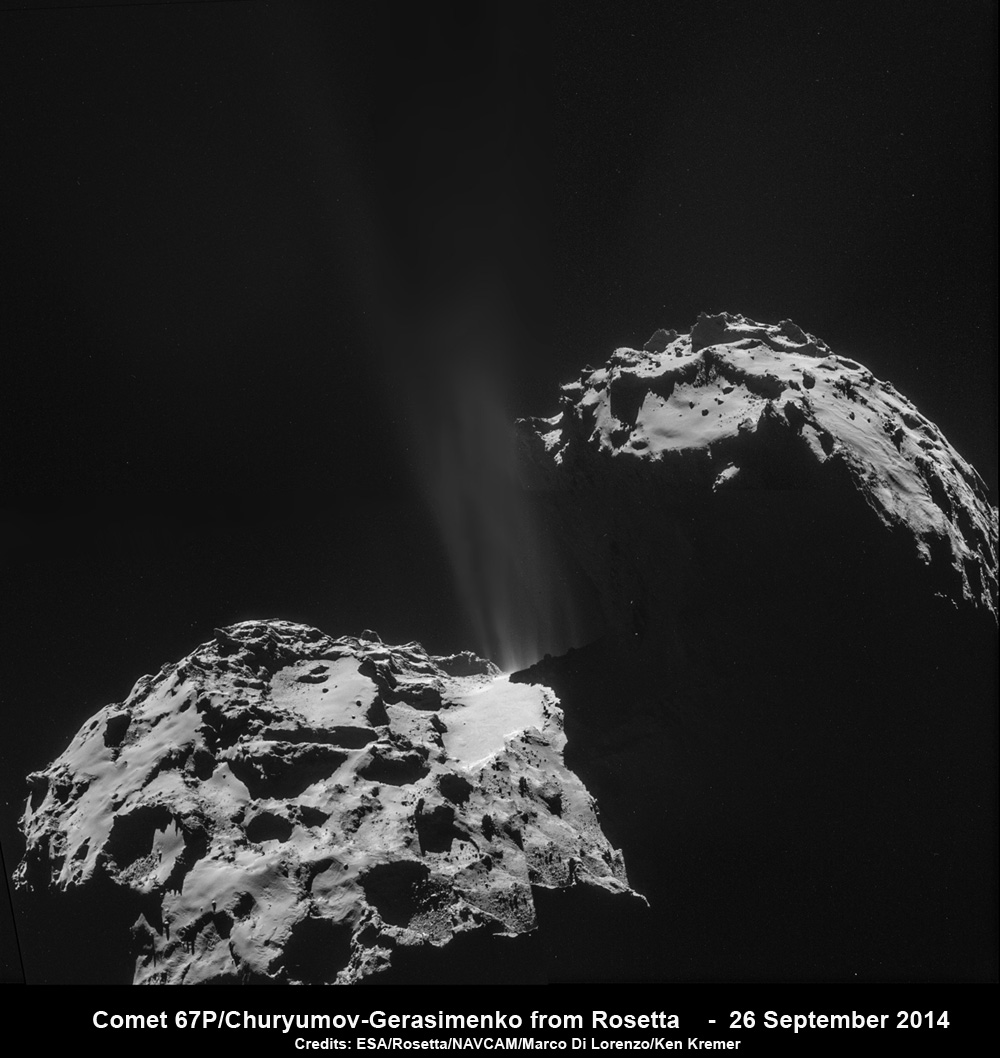

A spectacular display of celestial fireworks like none ever witnessed before, burst forth from Rosetta’s comet right on time – commemorating the Europeans spacecraft’s history making perihelion passage after a year long wait of mounting excitement and breathtaking science.

As the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Rosetta marked its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) at exactly 02:03 GMT on Thursday, August 13, 2015, while orbiting Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, its suite of 11 state-of-the-art science instruments, cameras and spectrometers were trained on the utterly bizarre bi-lobed body to capture every facet of the comet’s nature and environment for analysis by the gushing science teams.

And the perihelion passage did not disappoint – living up to its advance billing by spewing forth an unmatched display of otherworldly outbursts of gas jets and dust particles due to surface heating from the warming effects of the sun as the comet edged ever closer, coming within 186 million kilometers of mighty Sol.

ESA has released a brand new series of images, shown above and below, documenting sparks flying – as seen by Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera and NAVCAM wider angle cameras on August 12 and 13 – just a few hours before the rubby ducky shaped comet reached perihelion along its 6.5-year orbit around the sun.

Indeed the navcam camera image below was taken just an hour before the moment of perihelion, at 01:04 GMT, from a distance of around 327 kilometers!

Frozen ices are seen blasting away from the comet in a hail of gas and dust particles as rising solar radiation heats the nucleus and fortifies the comet’s atmosphere, or coma, and its tail.

After a decade long chase of over 6.4 billion kilometers (4 Billion miles), ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft arrived at the pockmarked Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko exactly a year ago on Aug. 6, 2014 for history’s first ever attempt to orbit a comet for long term study.

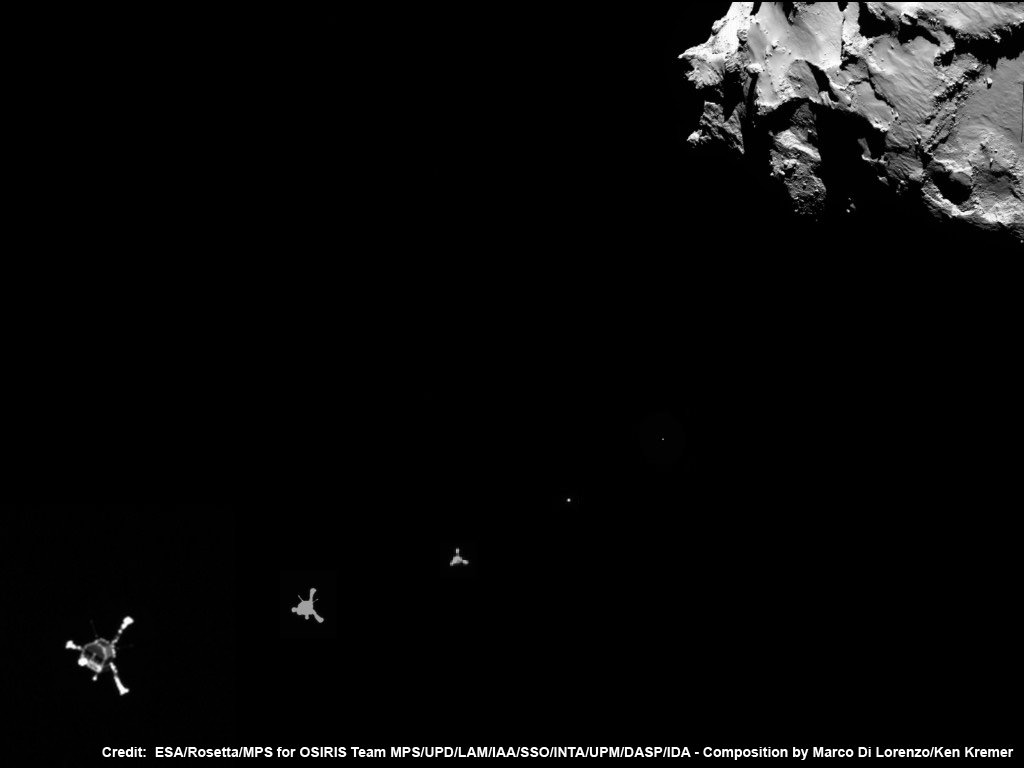

In the interim, Rosetta also deployed the piggybacked Philae lander for history’s first landing on a comet on Nov. 12, 2014.

In fact, measurements from Rosetta’s science instruments confirm the comet is belching a thousand times more water vapor today than was observed during Rosetta’s arrival a year ago. It’s spewing some 300 kg of water vapour every second now, compared to just 300 g per second upon arrival. That equates to two bathtubs per second now in Aug. 2015 vs. two small glasses of water per second in Aug. 2014.

Besides gas, 1000 kg of dust per second is simultaneously erupting from the nucleus, “creating dangerous working conditions for Rosetta,” says ESA.

“In recent days, we have been forced to move even further away from the comet. We’re currently at a distance of between 325 km and 340 km this week, in a region where Rosetta’s startrackers can operate without being confused by excessive dust levels – without them working properly, Rosetta can’t position itself in space,” comments Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s spacecraft operations manager, in an ESA statement.

Here’s an OSIRIS image taken just hours prior to perihelion, that’s included in the lead animation of this story.

The period of the comet’s peak intensity, as seen in all these images, is expected to continue past perihelion for several weeks at least and fulfils the dreams of a scientific goldmine for all the research teams and hundreds of researchers involved with Rosetta and Philae.

“Activity will remain high like this for many weeks, and we’re certainly looking forward to seeing how many more jets and outburst events we catch in the act, as we have already witnessed in the last few weeks,” says Nicolas Altobelli, acting Rosetta project scientist.

And Rosetta still has lots of fuel, and just as important – funding – to plus up its ground breaking science discoveries.

ESA recently granted Rosetta a 9 month mission extension to continue its research activities as well as having been given the chance to accomplish one final and daring historic challenge.

Engineers will attempt to boldly go and land the probe on the undulating surface of the comet.

Officials with the European Space Agency (ESA) gave the “GO” on June 23 saying “The adventure continues” for Rosetta to march forward with mission operations until the end of September 2016.

If all continues to go well “the spacecraft will most likely be landed on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” said ESA.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

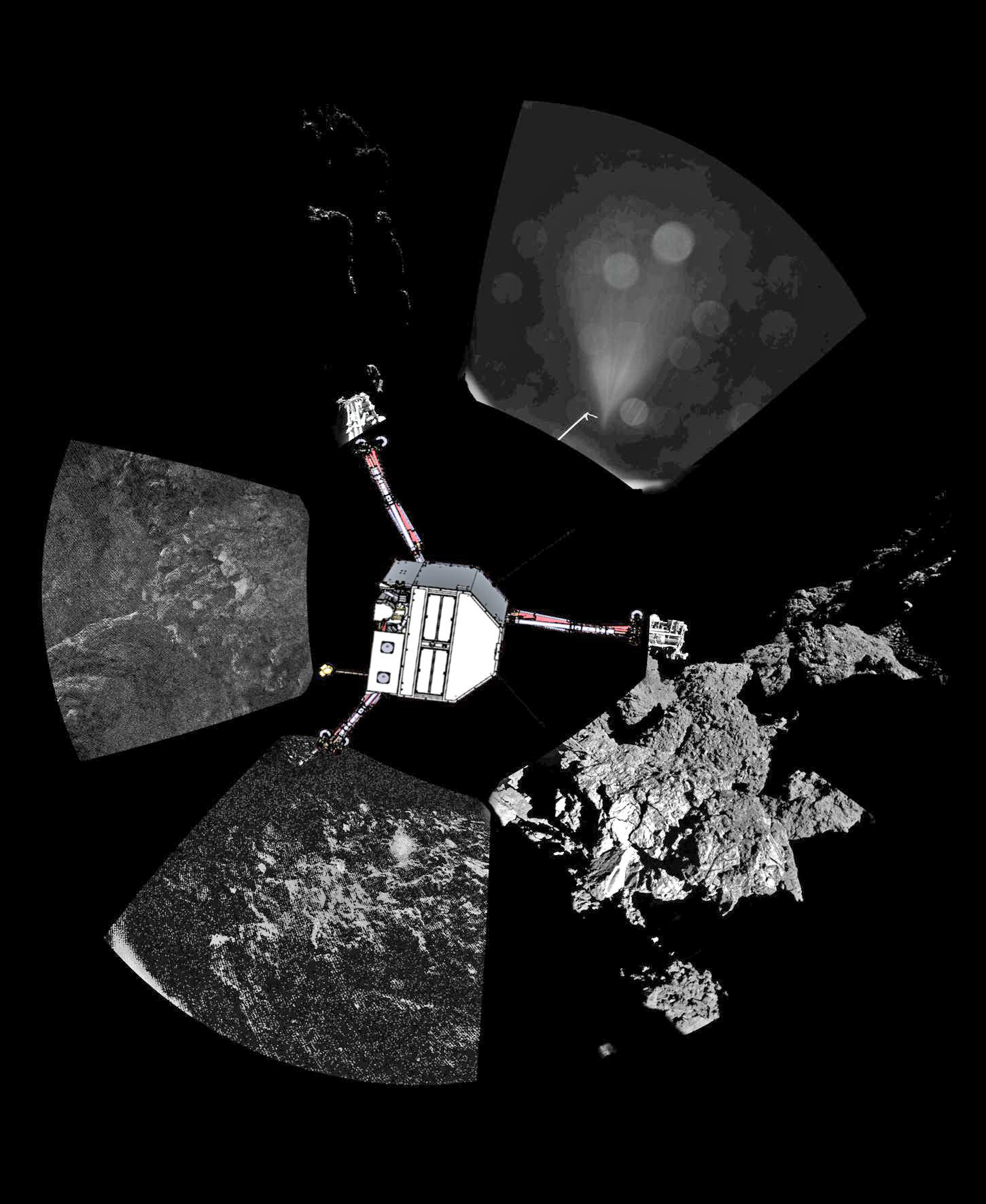

Why is it Tough to Land on a Comet?

Why is landing on a comet so difficult and what does this tell us about future missions to comets and asteroids?

Us nerds were riveted by the coverage of the ESA’s Rosetta mission and its arrival at Comet 67/P in 2014. One such nerd is Paco Juarez, friend of the show and patron. He wanted to know why is it so darned hard to land on a comet?

In 2014, the tiny Philae Lander detached from the spacecraft and slowly descended down to the surface of the comet. If everything went well, it would have gracefully touched down and then sent back a pile of information about this filthy roving snowball.

As you know, the landing didn’t go according to plan. Instead of gently touching down on 67/P, Philae bounced off the surface of the comet like a tennis ball dropped from a tower, and rose a kilometer off the surface. Then more descending, and more bouncing, finally settling down on rugged terrain, surrounded by crevices and large boulders. At that point, engineers lost contact with the lander, and so much science went undone.

If I recorded this video a few months ago, that would have been the end of the story. You know how this goes, space exploration is hard and dangerous, don’t be surprised when your missions fail and space unfeelingly smashes up your pretty little robot probes with their little gold foil 27 pieces of flair.

Fortunately, I’m able to report that ESA regained contact with the Philae lander on June 13, 2015, resuming its mission, and scientific operations.

But why is landing on a comet so difficult and what does this tell us about future robotic and human missions to smaller comets and asteroids? When ESA engineers designed Philae, they knew it was going to be very difficult to land on a comet like 67/P because they have a such a low gravity. And they have low gravity because they’re little.

On Earth, 6 septillion tonnes of rock and metal give you an escape velocity of 11.2 km/s. That’s how fast you need to be able to jump in order to leave the planet entirely. But the escape velocity of 67/P is only 1 m/s. You could trip off the comet and never return. Whilst small children threw rocks at you from the surface as you drifted away.

Philae was built with harpoon drills in its landing struts. The moment the lander touched the surface of the comet, those harpoons were supposed to fire, securing the lander. The surface of the comet was softer than scientists had anticipated, and the harpoons didn’t fire. Or possibly they were broken and couldn’t fire. Space is hard. Whatever the case, without being able to grab onto the surface, it used the comet as a bouncy castle.

We’re learning what it takes to land on lower mass objects like comets and asteroids. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission will visit Comet Bennu, and send a lander down to the surface of the asteroid. From there it’ll pick up a few samples, and return them back to Earth. It’ll be Philae, all over again.

In the future, we’re told, humans will be visiting asteroids to study them for science and their potential for ice and minerals. You can imagine it’ll be a harrowing descent, but even just walking around on the surface will be dangerous when every step could throw an astronaut into an escape trajectory. They’ll need to learn lessons from rock climbers and Rorschach.

As we learned with Philae, landings on low mass objects is really tough. We’re going to need to get more practice and develop new techniques and technologies before we’re ready to add asteroid mining to our list of “stuff we just do, NBD”.

What are some unusual worlds you’d like humanity to visit? Put your suggestions in the comments below.

What is the Oort Cloud?

For thousands of years, astronomers have watched comets travel close to Earth and light up the night sky. In time, these observations led to a number of paradoxes. For instance, where were these comets all coming from? And if their surface material vaporizes as they approach the Sun (thus forming their famous halos), they must formed farther away, where they would have existed there for most of their lifespans.

In time, these observations led to the theory that far beyond the Sun and planets, there exists a large cloud of icy material and rock where most of these comets come from. This existence of this cloud, which is known as the Oort Cloud (after its principal theoretical founder), remains unproven. But from the many short and long-period comets that are believed to have come from there, astronomers have learned a great deal about it structure and composition.

Definition:

The Oort Cloud is a theoretical spherical cloud of predominantly icy planetesimals that is believed to surround the Sun at a distance of up to around 100,000 AU (2 ly). This places it in interstellar space, beyond the Sun’s Heliosphere where it defines the cosmological boundary between the Solar System and the region of the Sun’s gravitational dominance.

Like the Kuiper Belt and the Scattered Disc, the Oort Cloud is a reservoir of trans-Neptunian objects, though it is over a thousands times more distant from our Sun as these other two. The idea of a cloud of icy infinitesimals was first proposed in 1932 by Estonian astronomer Ernst Öpik, who postulated that long-period comets originated in an orbiting cloud at the outermost edge of the Solar System.

In 1950, the concept was resurrected by Jan Oort, who independently hypothesized its existence to explain the behavior of long-term comets. Although it has not yet been proven through direct observation, the existence of the Oort Cloud is widely accepted in the scientific community.

Structure and Composition:

The Oort Cloud is thought to extend from between 2,000 and 5,000 AU (0.03 and 0.08 ly) to as far as 50,000 AU (0.79 ly) from the Sun, though some estimates place the outer edge as far as 100,000 and 200,000 AU (1.58 and 3.16 ly). The Cloud is thought to be comprised of two regions – a spherical outer Oort Cloud of 20,000 – 50,000 AU (0.32 – 0.79 ly), and disc-shaped inner Oort (or Hills) Cloud of 2,000 – 20,000 AU (0.03 – 0.32 ly).

The outer Oort cloud may have trillions of objects larger than 1 km (0.62 mi), and billions that measure 20 kilometers (12 mi) in diameter. Its total mass is not known, but – assuming that Halley’s Comet is a typical representation of outer Oort Cloud objects – it has the combined mass of roughly 3×1025 kilograms (6.6×1025 pounds), or five Earths.

Based on the analyses of past comets, the vast majority of Oort Cloud objects are composed of icy volatiles – such as water, methane, ethane, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and ammonia. The appearance of asteroids thought to be originating from the Oort Cloud has also prompted theoretical research that suggests that the population consists of 1-2% asteroids.

Earlier estimates placed its mass up to 380 Earth masses, but improved knowledge of the size distribution of long-period comets has led to lower estimates. The mass of the inner Oort Cloud, meanwhile, has yet to be characterized. The contents of both Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud are known as Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), because the objects of both regions have orbits that that are further from the Sun than Neptune’s orbit.

Origin:

The Oort cloud is thought to be a remnant of the original protoplanetary disc that formed around the Sun approximately 4.6 billion years ago. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that the Oort cloud’s objects initially coalesced much closer to the Sun as part of the same process that formed the planets and minor planets, but that gravitational interaction with young gas giants such as Jupiter ejected them into extremely long elliptic or parabolic orbits.

Recent research by NASA suggests that a large number of Oort cloud objects are the product of an exchange of materials between the Sun and its sibling stars as they formed and drifted apart. It is also suggested that many – possibly the majority – of Oort cloud objects were not formed in close proximity to the Sun.

Alessandro Morbidelli of the Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur has conducted simulations on the evolution of the Oort cloud from the beginnings of the Solar System to the present. These simulations indicate that gravitational interaction with nearby stars and galactic tides modified cometary orbits to make them more circular. This is offered as an explanation for why the outer Oort Cloud is nearly spherical in shape while the Hills cloud, which is bound more strongly to the Sun, has not acquired a spherical shape.

Recent studies have shown that the formation of the Oort cloud is broadly compatible with the hypothesis that the Solar System formed as part of an embedded cluster of 200–400 stars. These early stars likely played a role in the cloud’s formation, since the number of close stellar passages within the cluster was much higher than today, leading to far more frequent perturbations.

Comets:

Comets are thought to have two points of origin within the Solar System. They start as infinitesimals in the Oort Cloud and then become comets when passing stars knock some of them out of their orbits, sending into a long-term orbit that take them into the inner solar system and out again.

Short-period comets have orbits that last up to two hundred years while the orbits of long-period comets can last for thousands of years. Whereas short-period comets are believed to have emerged from either the Kuiper Belt or the scattered disc, the accepted hypothesis is that long-period comets originate in the Oort Cloud. However, there are some exceptions to this rule.

For example, there are two main varieties of short-period comet: Jupiter-family comets and Halley-family comets. Halley-family comets, named for their prototype (Halley’s Comet) are unusual in that although they are short in period, they are believed to have originated from the Oort cloud. Based on their orbits, it is suggested they were once long-period comets that were captured by the gravity of a gas giant and sent into the inner Solar System.

Exploration:

Because the Oort Cloud is so much farther out than the Kuiper Belt, the region remained unexplored and largely undocumented. Space probes have yet to reach the area of the Oort cloud, and Voyager 1 – the fastest and farthest of the interplanetary space probes currently exiting the Solar System – is not likely to provide any information on it.

At its current speed, Voyager 1 will reach the Oort cloud in about 300 years, and will will take about 30,000 years to pass through it. However, by around 2025, the probe’s radioisotope thermoelectric generators will no longer supply enough power to operate any of its scientific instruments. The other four probes currently escaping the Solar System – Voyager 2, Pioneer 10 and 11, and New Horizons – will also be non-functional when they reach the Oort cloud.

Exploring the Oort Cloud presents numerous difficulties, most of which arise from the fact that it is incredible distant from Earth. By the time a robotic probe could actually reach it and begin exploring the area in earnest, centuries will have passed here on Earth. Not only would those who had sent it out in the first place be long dead, but humanity will have most likely invented far more sophisticated probes or even manned craft in the meantime.

Still, studies can be (and are) conducted by examining the comets that it periodically spits out, and long-range observatories are likely to make some interesting discoveries from this region of space in the coming years. It’s a big cloud. Who knows what we might find lurking in there?

We have many interesting articles about the Oort Cloud and Solar System for Universe Today. Here’s an article about how big the Solar System is, and one on the diameter of the Solar System. And here’s all you need to know about Halley’s Comet and Beyond Pluto.

You might also want to check out this article from NASA on the Oort Cloud and one from the University of Michigan on the origin of comets.

Do not forget to take a look at the podcast from Astronomy Cast. Episode 64: Pluto and the Icy Outer Solar System and Episode 292: The Oort Cloud.

Reference:

NASA Solar System Exploration: Kuiper Belt & Oort Cloud

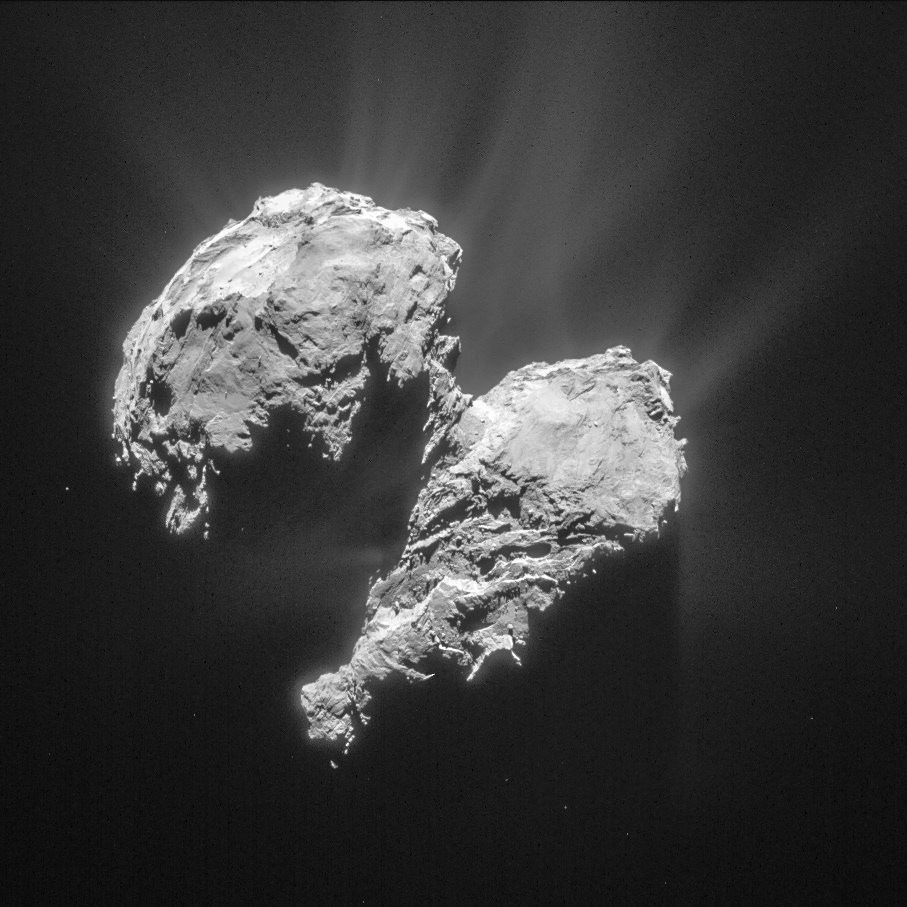

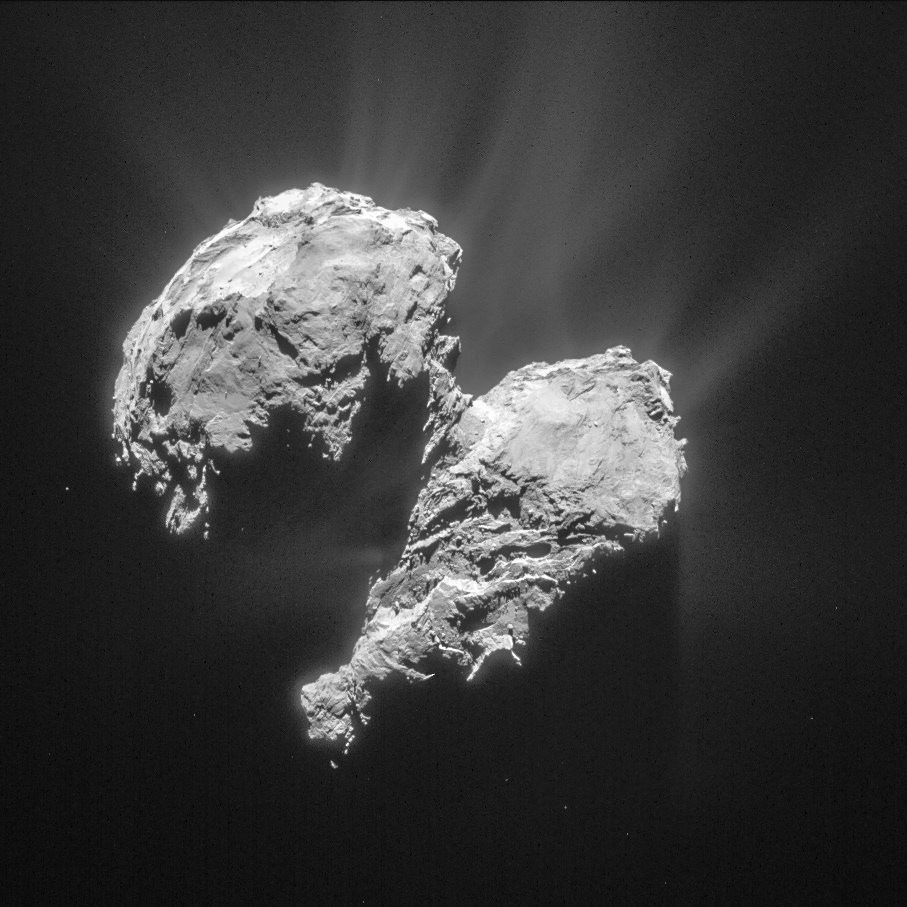

Rosetta Orbiter Approved for Extended Mission and Bold Comet Landing

Rosetta will attempt comet landing

This single frame Rosetta navigation camera image of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko was taken on 15 June 2015 from a distance of 207 km from the comet centre. The image has a resolution of 17.7 m/pixel and measures 18.1 km across. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 [/caption]

Europe’s history making Rosetta cometary spacecraft has been granted a nine month mission extension to plus up its bountiful science discoveries as well as been given the chance to accomplish one final and daring historic challenge, as engineers attempt to boldly go and land the probe on the undulating surface of the comet its currently orbiting.

Officials with the European Space Agency (ESA) gave the “GO” on June 23 saying “The adventure continues” for Rosetta to march forward with mission operations until the end of September 2016.

If all continues to go well “the spacecraft will most likely be landed on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” said ESA to the unabashed glee of the scientists and engineers responsible for leading Rosetta and reaping the rewards of nearly a year of groundbreaking research since the probe arrived at comet 67P in August 2014.

“This is fantastic news for science,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta Project Scientist, in a statement.

It will take about 3 months for Rosetta to spiral down to the surface.

After a decade long chase of over 6.4 billion kilometers (4 Billion miles), ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft arrived at the pockmarked Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Aug. 6, 2014 for history’s first ever attempt to orbit a comet for long term study.

Since then, Rosetta deployed the piggybacked Philae landing craft to accomplish history’s first ever touchdown on a comets nucleus on November 12, 2014. It has also orbited the comet for over 10 months of up close observation, coming at times to as close as 8 kilometers. It is equipped with a suite 11 instruments to analyze every facet of the comet’s nature and environment.

Currently, Comet 67P is still becoming more and more active as it orbits closer and closer to the sun over the next two months. The mission extension will enable researchers to a far greater period of time to compare the comets activity, physical and chemical properties and evolution ‘before and after’ they arrive at perihelion some six weeks from today.

The pair reach perihelion on August 13, 2015 at a distance of 186 million km from the Sun, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

“We’ll be able to monitor the decline in the comet’s activity as we move away from the Sun again, and we’ll have the opportunity to fly closer to the comet to continue collecting more unique data. By comparing detailed ‘before and after’ data, we’ll have a much better understanding of how comets evolve during their lifetimes.”

Because the comet is nearly at its peak of outgassing and dust spewing activity, Rosetta must observe the comet from a stand off distance, while still remaining at a close proximity, to avoid damage to the probe and its instruments.

Furthermore, the Philae lander “awoke” earlier this month after entering a sven month hibernation period after successfully compleing some 60 hours of science observations from the surface.

As the comet again edges away from the sun and becomes less active, the team will attempt to land Rosetta on comet 67P before it runs out of fuel and the energy produced from the huge solar panels is insufficient to continue mission operations.

“This time, as we’re riding along next to the comet, the most logical way to end the mission is to set Rosetta down on the surface,” says Patrick Martin, Rosetta Mission Manager.

“But there is still a lot to do to confirm that this end-of-mission scenario is possible. We’ll first have to see what the status of the spacecraft is after perihelion and how well it is performing close to the comet, and later we will have to try and determine where on the surface we can have a touchdown.”

During the extended mission, the team will use the experience gained in operating Rosetta in the challenging cometary environment to carry out some new and potentially slightly riskier investigations, including flights across the night-side of the comet to observe the plasma, dust, and gas interactions in this region, and to collect dust samples ejected close to the nucleus, says ESA.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

………….

Learn more about Rosetta, SpaceX, Europa, Mars rovers, Orion, SLS, Antares, NASA missions and more at Ken’s upcoming outreach events:

Jun 25-28: “SpaceX launch, Orion, Commercial crew, Curiosity explores Mars, Antares and more,” Kennedy Space Center Quality Inn, Titusville, FL, evenings

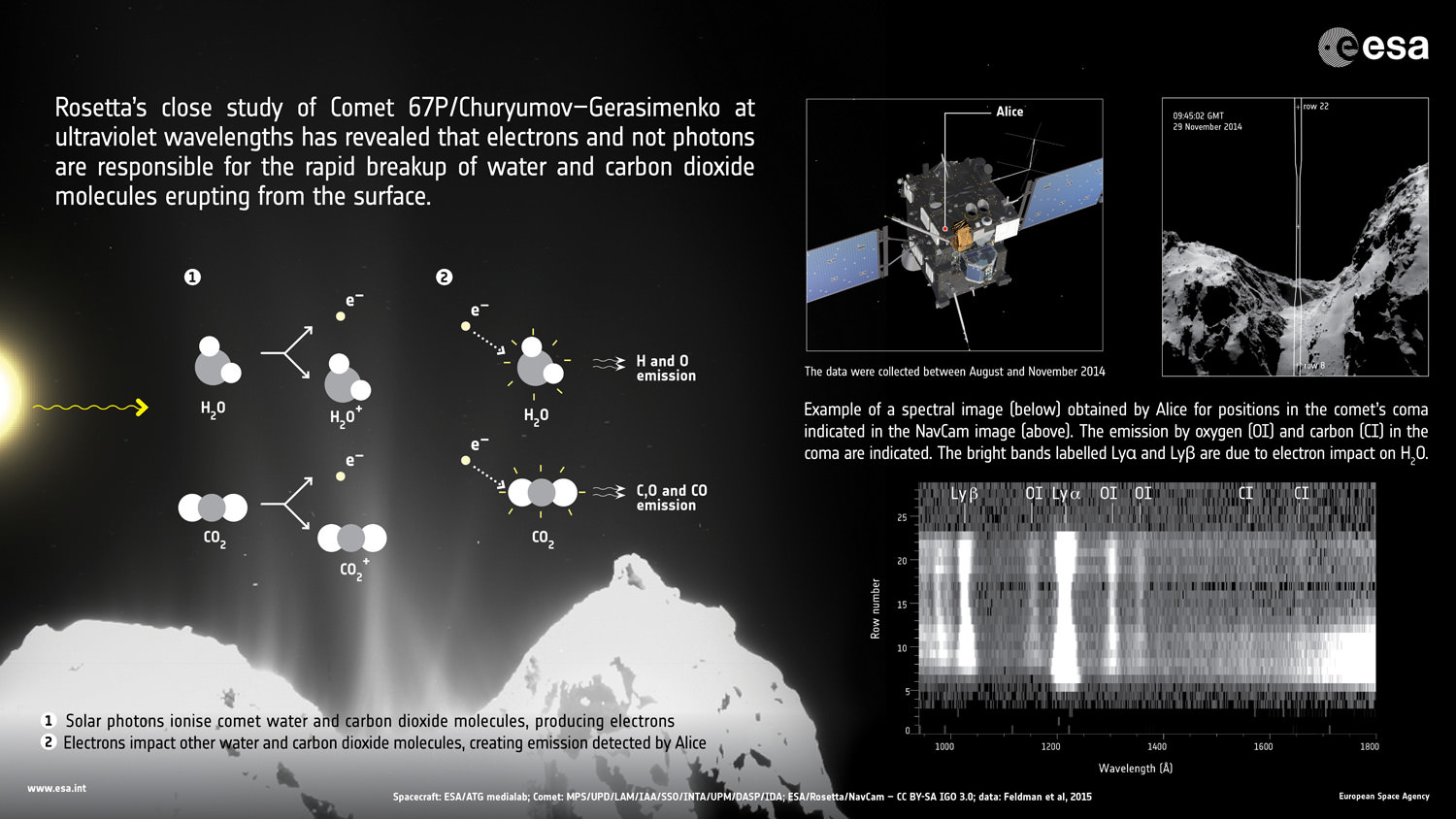

Rosetta Discovery of Surprise Molecular Breakup Mechanism in Comet Coma Alters Perceptions

A NASA science instrument flying aboard the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft has made a very surprising discovery – namely that the molecular breakup mechanism of “water and carbon dioxide molecules spewing from the comet’s surface” into the atmosphere of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is caused by “electrons close to the surface.”

The surprising results relating to the emission of the comet coma came from measurements gathered by the probes NASA funded Alice instrument and is causing scientists to completely rethink what we know about the wandering bodies, according to the instruments science team.

“The discovery we’re reporting is quite unexpected,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator for the Alice instrument at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, in a statement.

“It shows us the value of going to comets to observe them up close, since this discovery simply could not have been made from Earth or Earth orbit with any existing or planned observatory. And, it is fundamentally transforming our knowledge of comets.”

A paper reporting the Alice findings has been accepted for publication by the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, according to statements from NASA and ESA.

Alice is a spectrograph that focuses on sensing the far-ultraviolet wavelength band and is the first instrument of its kind to operate at a comet.

Until now it had been thought that photons from the sun were responsible for causing the molecular breakup, said the team.

The carbon dioxide and water are being released from the nucleus and the excitation breakup occurs barely half a mile above the comet’s nucleus.

“Analysis of the relative intensities of observed atomic emissions allowed the Alice science team to determine the instrument was directly observing the “parent” molecules of water and carbon dioxide that were being broken up by electrons in the immediate vicinity, about six-tenths of a mile (one kilometer) from the comet’s nucleus.”

The excitation mechanism is detailed in the graphic below.

“The spatial variation of the emissions along the slit indicates that the excitation occurs within a few hundred meters of the surface and the gas and dust production are correlated,” according to the Astronomy and Astrophysics journal paper.

The data shows that the water and CO2 molecules break up via a two-step process.

“First, an ultraviolet photon from the Sun hits a water molecule in the comet’s coma and ionises it, knocking out an energetic electron. This electron then hits another water molecule in the coma, breaking it apart into two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen, and energising them in the process. These atoms then emit ultraviolet light that is detected at characteristic wavelengths by Alice.”

“Similarly, it is the impact of an electron with a carbon dioxide molecule that results in its break-up into atoms and the observed carbon emissions.”

After a decade long chase of over 6.4 billion kilometers (4 Billion miles), ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft arrived at the pockmarked Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Aug. 6, 2014 for history’s first ever attempt to orbit a comet for long term study.

Since then, Rosetta deployed the Philae landing craft to accomplish history’s first ever touchdown on a comets nucleus. It has also orbited the comet for over 10 months of up close observation, coming at times to as close as 8 kilometers. It is equipped with a suite 11 instruments to analyze every facet of the comet’s nature and environment.

Comet 67P is still becoming more and more active as it orbits closer and closer to the sun over the next two months. The pair reach perihelion on August 13, 2015 at a distance of 186 million km from the Sun, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

Alice works by examining light emitted from the comet to understand the chemistry of the comet’s atmosphere, or coma and determine the chemical composition with the far-ultraviolet spectrograph.

According to the measurements from Alice, the water and carbon dioxide in the comet’s atmospheric coma originate from plumes erupting from its surface.

“It is similar to those that the Hubble Space Telescope discovered on Jupiter’s moon Europa, with the exception that the electrons at the comet are produced by solar radiation, while the electrons at Europa come from Jupiter’s magnetosphere,” said Paul Feldman, an Alice co-investigator from the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, in a statement.

Other instruments aboard Rosetta including MIRO, ROSINA and VIRTIS, which study relative abundances of coma constituents, corroborate the Alice findings.

“These early results from Alice demonstrate how important it is to study a comet at different wavelengths and with different techniques, in order to probe various aspects of the comet environment,” says ESA’s Rosetta project scientist Matt Taylor, in a statement.

“We’re actively watching how the comet evolves as it moves closer to the Sun along its orbit towards perihelion in August, seeing how the plumes become more active due to solar heating, and studying the effects of the comet’s interaction with the solar wind.”

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.