Mapping the Universe with satellites and ground-based observatories have not only provided scientists with a pretty good understanding of its structure, but also of its composition. And for some time now, they have been working with a model that states that the Universe consists of 4.9% “normal” matter (i.e. that which we can see), 26.8% “dark matter” (that which we can’t), and 68.3% “dark energy”.

From what they have observed, scientists have also concluded that the normal matter in the Universe is concentrated in web-like filaments, which make up about 20% of the Universe by volume. But a recent study performed by the Institute of Astro- and Particle Physics at the University of Innsbruck in Austria has found that a surprising amount of normal matter may live in the voids, and that black holes may have deposited it there.

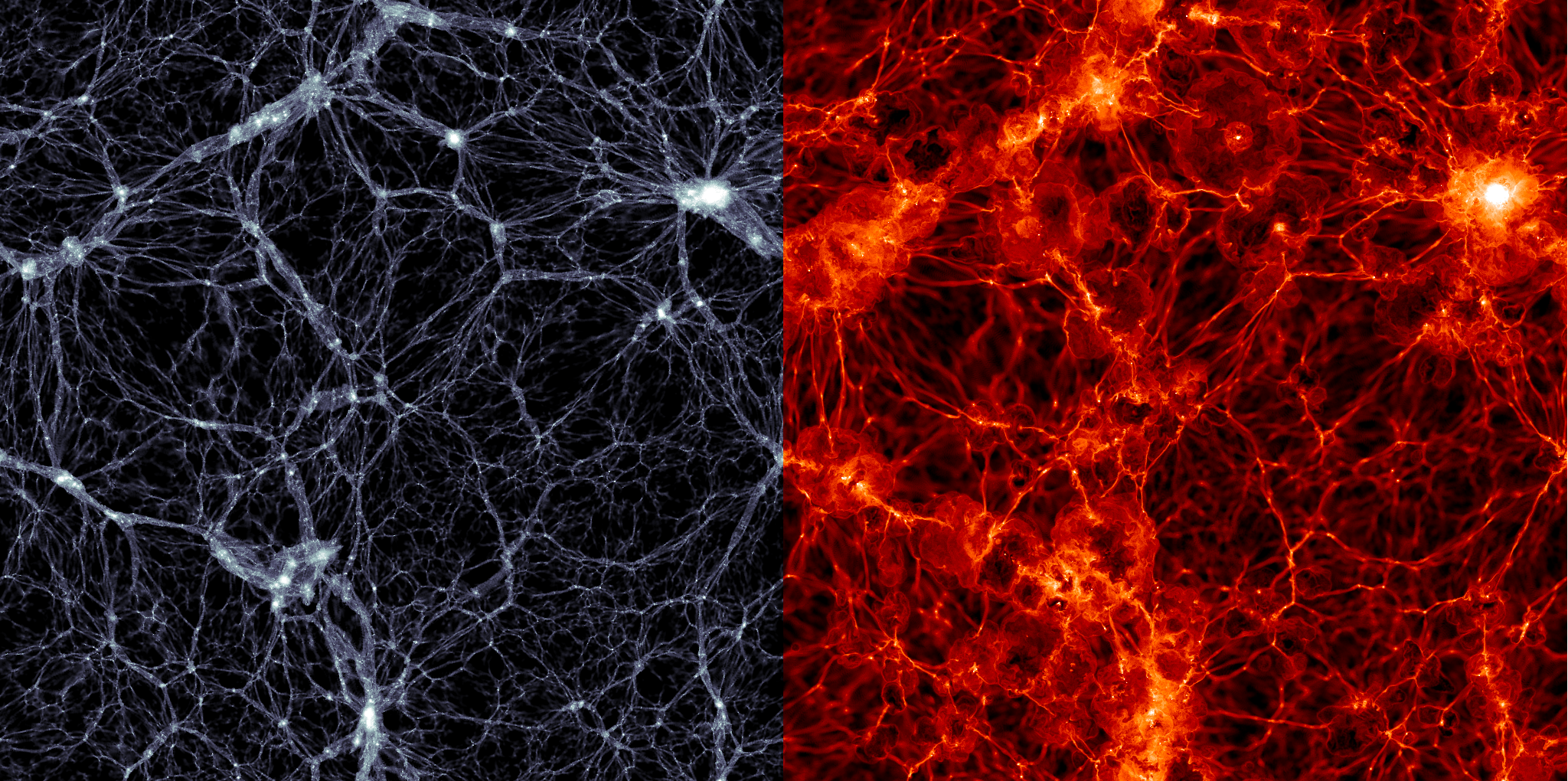

In a paper submitted to the Royal Astronomical Society, Dr. Haider and his team described how they performed measurements of the mass and volume of the Universe’s filamentary structures to get a better idea of where the Universe’s mass is located. To do this, they used data from the Illustris project – a large computer simulation of the evolution and formation of galaxies.

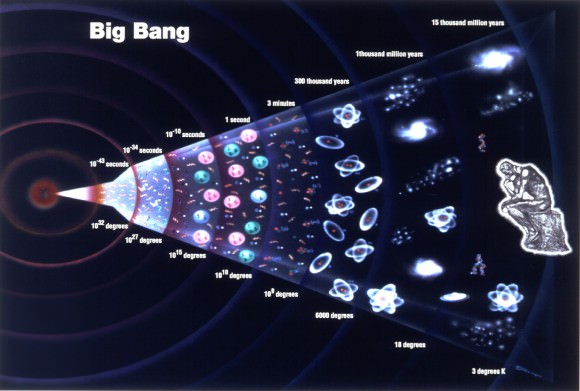

As an ongoing research project run by an international collaboration of scientists (and using supercomputers from around the world), Illustris has created the most detailed simulations of our Universe to date. Beginning with conditions roughly 300,000 years after the Big Bang, these simulations track how gravity and the flow of matter changed the structure of the cosmos up to the present day, roughly 13.8 billion years later.

The process begins with the supercomputers simulating a cube of space in the universe, which measures some 350 million light years on each side. Both normal and dark matter are dealt with, particularly the gravitational effect that dark matter has on normal matter. Using this data, Haider and his team noticed something very interesting about the distribution of matter in the cosmos.

Essentially, they found that about 50% of the total mass of the Universe is compressed into a volume of 0.2%, consisting of the galaxies we see. A further 44% is located in the enveloping filaments, consisting of gas particles and dust. The remaining 6% is located in the empty spaces that fall between them (aka. the voids), which make up 80% of the Universe.

However, a surprising faction of this normal matter (20%) appears to have been transported there, apparently by the supermassive black holes located at the center of galaxies. The method for this delivery appears to be in how black holes convert some of the matter that regularly falls towards them into energy, which is then delivered to the sounding gas, leading to large outflows of matter.

These outflows stretch for hundreds of thousands of lights years beyond the host galaxy, filling the void with invisible mass. As Dr. Haider explains, these conclusions supported by this data are rather startling. “This simulation,” he said, “one of the most sophisticated ever run, suggests that the black holes at the center of every galaxy are helping to send matter into the loneliest places in the universe. What we want to do now is refine our model, and confirm these initial findings.”

The findings are also significant because they just may offer an explanation to the so-called “missing baryon problem”. In short, this problem describes how there is an apparent discrepancy between our current cosmological models and the amount of normal matter we can see in the Universe. Even when dark matter and dark energy are factored in, half of the remaining 4.9% of the Universe’s normal matter still remains unaccounted for.

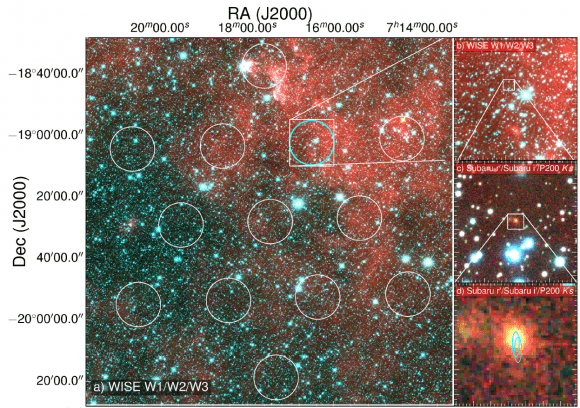

For decades, scientists have been working to find this “missing matter”, and several suggestions have been made as to where it might be hiding. For instance, in 2011, a team of students at the Monash School of Physics in Australia confirming that some of it was in the form of low-density, high energy matter that could only be observed in the x-ray wavelength.

In 2012, using data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, a NASA research team reported that our galaxy, and the nearby Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, were surrounded by an enormous halo of hot gas that was invisible at normal wavelengths. These findings indicated that all galaxies may be surrounded by mass that, while not visible to the naked eye, is nevertheless detectable using current methods.

And just days ago, researchers from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) described how they had used fast radio bursts (FRBs) to measure the density of cosmic baryons in the intergalactic medium – which yielded results that seem to indicate that our current cosmological models are correct.

Factor in all the mass that is apparently being delivered to the void by supermassive black holes, and it could be that we finally have a complete inventory of all the normal matter of the Universe. This is certainly an exciting prospect, as it means that one of the greatest cosmological mysteries of our time could finally be solved.

Now if we could just account for the “abnormal” matter in the Universe, and all that dark energy, we’d be in business!

Further Reading: Royal Astronomical Society