Can low-mass stars play host to giant, Jupiter-sized planets? Theories of planet formation suggest that it’s highly unlikely. But a team of scientists in the UK found that it’s possible, though rare.

Continue reading “TESS Shows That Even Small Stars Can Host Giant Planets”First Exoplanet Discovered Beyond the “Snow Line”

Data from NASA’s crippled Kepler space telescope has unleashed a windfall of hot Jupiters — sizzling gas giants that circle their host star within days — and only a handful of Earth-like planets. A quick analysis might make it seem as though hot Jupiters are far more common than their smaller and more distant counterparts.

But in large surveys, astronomers have to be careful of the observational biases introduced into their data. Kepler, for example, mainly finds broiling furnace worlds close to their host stars. These are easier to spot than small exoplanets that take hundreds of days to transit.

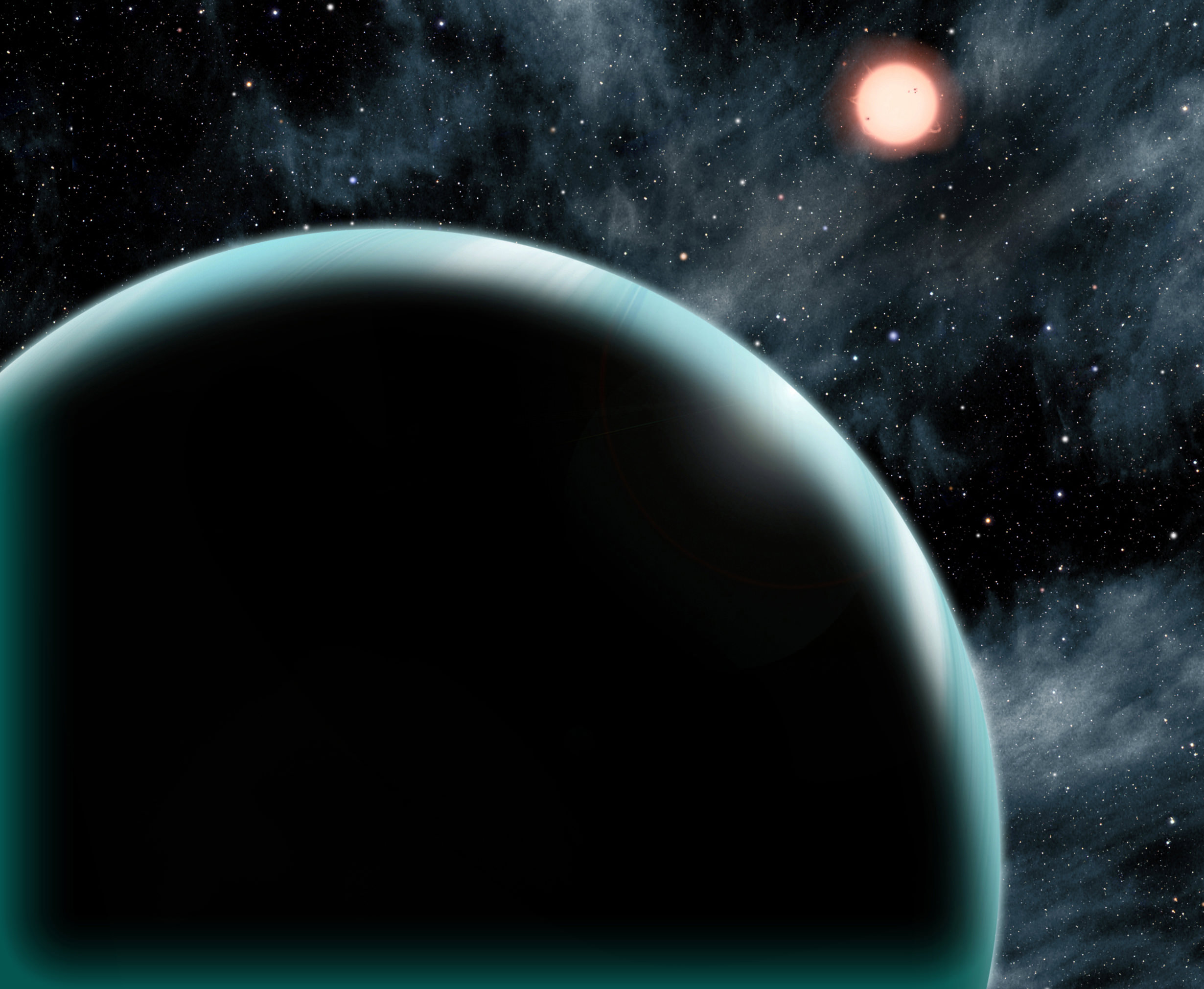

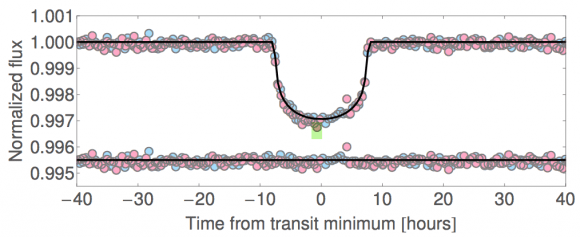

New data, however, shows a transiting exoplanet, Kepler-421b, with the longest known year, clocking in at 704 days.

“Finding Kepler-421b was a stroke of luck,” said lead author David Kipping from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in a press release. “The farther a planet is from its star, the less likely it is to transit the star from Earth’s point of view. It has to line up just right.”

Kepler-421b is roughly 4 times Earth’s girth and at least 60 times Earth’s mass. It circles its host star at about 1.2 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. But because its host star is much smaller than our Sun, this places its orbit beyond the snow line — the dividing line between rocky and gas planets.

On Earth, snow lines typically form at high elevations where falling temperatures turn atmospheric moisture to snow. Similarly, in planetary systems, snow lines are thought to form in the distant, colder reaches of the stars’ disk.

Depending on the distance from the star, however, other more exotic molecules — such as carbon dioxide, methane, and carbon monoxide — can freeze and turn to snow. This forms a frost on dust grains: the building blocks of planets and comets.

“The snow line is a crucial distance in planet formation theory. We think all gas giants must have formed beyond this distance,” said Kipping.

The fact that this gas giant is still beyond this distance, roughly 4 billion years after formation, suggests that it’s the first non-migrating gas giant in a transiting system found.

Astronomers currently think gas giants form by small rocky cores that glom together until the body is massive enough to accrete a gaseous envelope. As they grow, they migrate inward, sometimes moving as close to their host star as Mercury is to the Sun.

Kepler-421b may be the first exoplanet discovered to have formed in situ. But further observations, especially those of its atmosphere, will help shed light on its formation history. Unfortunately given its long year, it won’t transit again until February, 2016.

The research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and is available online.