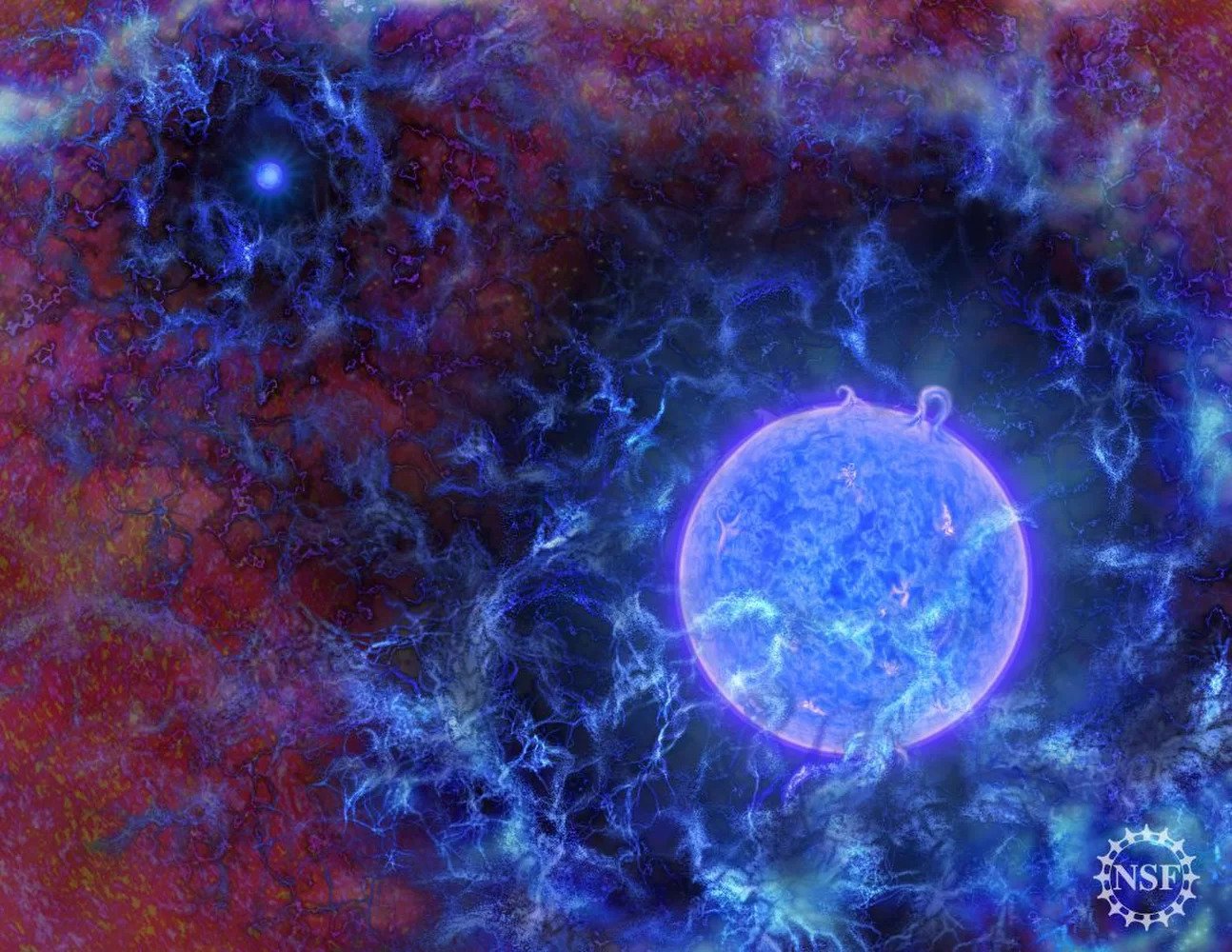

An enormous and incredibly luminous distant galaxy has turned out to actually be three galaxies in the process of merging together, based on the latest observations from ALMA as well as the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. Located 13 billion light-years away, this galactic threesome is being seen near the very beginning of what astronomers call the “Cosmic Dawn,” a time when the Universe first became illuminated by stars.

“This exceedingly rare triple system, seen when the Universe was only 800 million years old, provides important insights into the earliest stages of galaxy formation during a period known as ‘Cosmic Dawn’ when the Universe was first bathed in starlight,” said Richard Ellis, professor of astronomy at Caltech and member of the research team. “Even more interesting, these galaxies appear poised to merge into a single massive galaxy, which could eventually evolve into something akin to the Milky Way.”

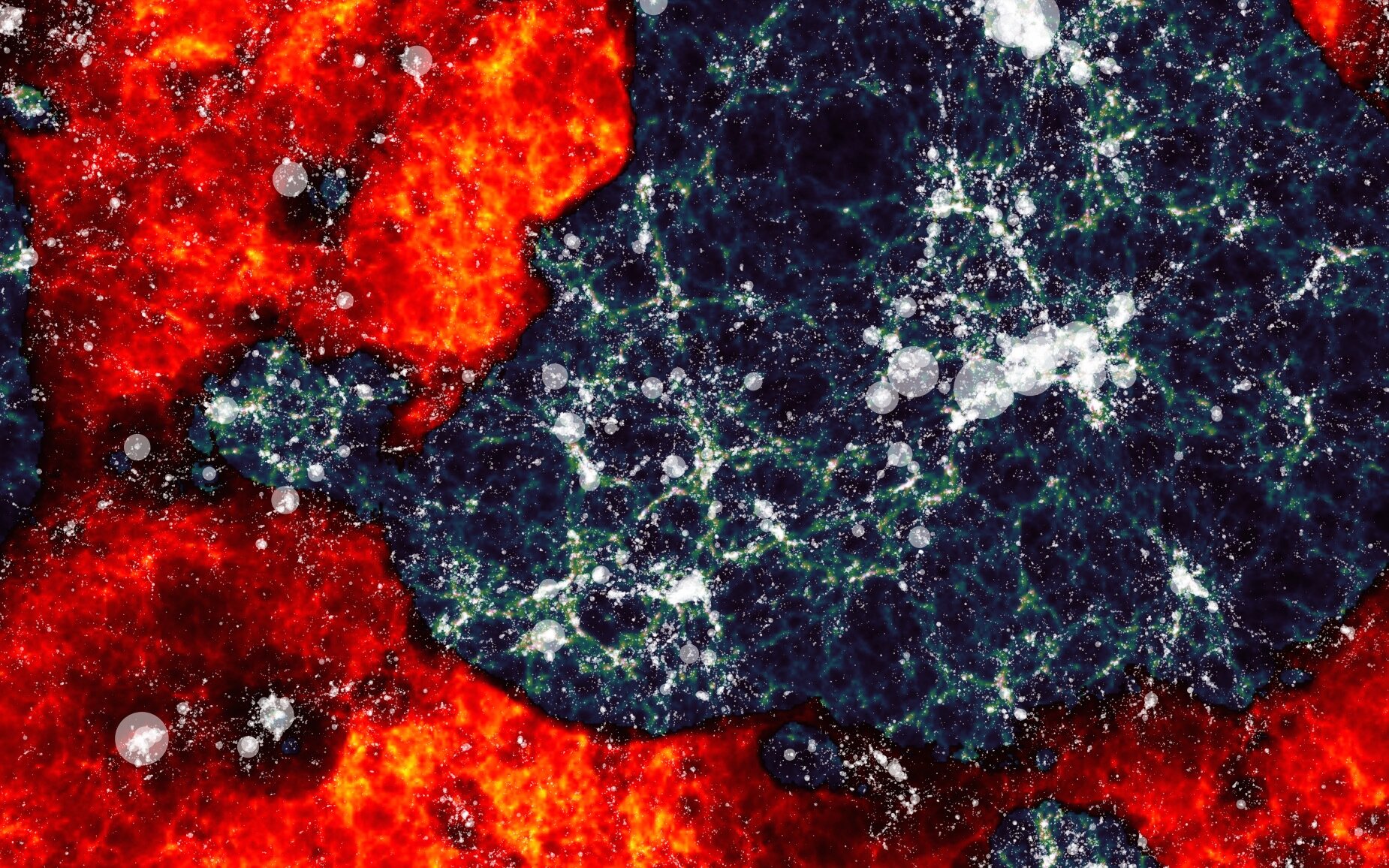

In the image above, infrared data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope are shown in red, visible data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope are green, and ultraviolet data from Japan’s Subaru telescope are blue. First discovered in 2009, the object is named “Himiko” after a legendary queen of Japan.

The merging galaxies within Himiko are surrounded by a vast cloud of hydrogen and helium, glowing brightly from the galaxies’ powerful outpouring of energy.

What’s particularly intriguing to astronomers is the noted lack of heavier elements like carbon in the cloud.

“This suggests that the gas cloud around the galaxy is actually quite primitive in its composition,” Ellis states in an NRAO video, “and has not yet been enriched by the products of nuclear fusion in the stars in the triple galaxy system. And what this implies is that the system is much younger and potentially what we call primeval… a first-generation object that is being seen. If true that’s very very exciting.”

Further research of distant objects like Himiko with the new high-resolution capabilities of ALMA will help astronomers determine how the Universe’s first galaxies “turned on”… was it a relatively sudden event, or did it occur gradually over many millions of years?

Watch the full video from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory below:

The research team’s results have been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

Source: NASA/JPL press release and the NRAO.