[/caption]

According to Wikipedia, a journal club is a group of individuals who meet regularly to critically evaluate recent articles in scientific literature. Being Universe Today if we occasionally stray into critically evaluating each other’s critical evaluations, that’s OK too. And of course, the first rule of Journal Club is… don’t talk about Journal Club.

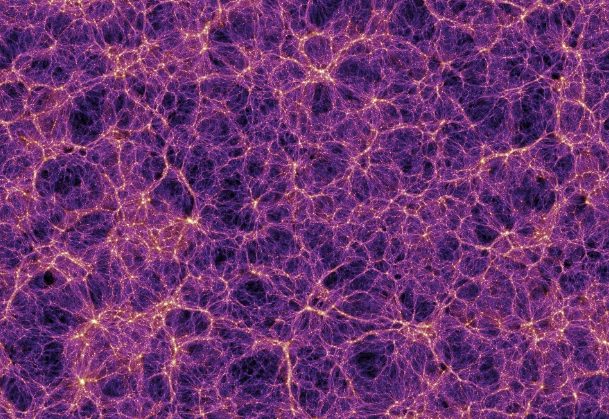

So, without further ado – today’s journal article on the dissection table is about using our limited understanding of dark matter to attempt visualise the cosmic web of the very early universe.

Today’s article:

Visbal et al The Grand Cosmic Web of the First Stars.

So… dark matter, pretty strange stuff huh? You can’t see it – which presumably means it’s transparent. Indeed it seems to be incapable of absorbing or otherwise interacting with light of any wavelength. So dark matter’s presence in the early universe should make it readily distinguishable from conventional matter – which does interact with light and so would have been heated, ionised and pushed around by the radiation pressure of the first stars.

This fundemental difference may lead to a way to visualise the early universe. To recap those early years, first there was the Big Bang, then three minutes later the first hydrogen nuclei formed, then 380,000 years later the first stable atoms formed. What follows from there is the so-called dark ages – until the first stars began to form from the clumping of cooled hydrogen. And according to the current standard model of Lambda Cold Dark Matter – this clumping primarily took place within gravity wells created by cold (i.e. static) dark matter.

This period is what is known as the reionization era, since the radiation of these first stars reheated the interstellar hydrogen medium and hence re-ionized it (back into a collection of H+ ions and unbound electrons).

While this is all well established cosmological lore – it is also the case that the radiation of the first stars would have applied a substantial radiation pressure on that early dense interstellar medium.

So, the early interstellar medium would not only be expanding due to the expansion of the universe, but also it would be being pushed outwards by the radiation of the first stars – meaning that there should be a relative velocity difference between the interstellar medium and the dark matter of the early universe – since the dark matter would be immune to any radiation pressure effects.

To visualize this relative velocity difference, we can look for hydrogen emissions, which are 21 cm wavelength light – unless further red-shifted, but in any case these signals are well into the radio spectrum. Radio astronomy observations at these wavelengths offer a window to enable observation of the distribution of the very first stars and galaxies – since these are the source of the first ionising radiation that differentiates the dark matter scaffolding (i.e. the gravity wells that support star and galaxy formation) from the remaining reionized interstellar medium. And so you get the first signs of the cosmic web when the universe was only 200 million years old.

Higher resolution views of this early cosmic web of primeval stars, galaxies and galactic clusters are becoming visible through high resolution radio astronomy instruments such as LOFAR – and hopefully one day in the not-too-distant future, the Square Kilometre Array – which will enable visualisation of the early universe in unprecedented detail.

So – comments? Does this fascinating observation of 21cm line absorption lines somehow lack the punch of a pretty Hubble Space Telescope image? Is radio astronomy just not sexy? Want to suggest an article for the next edition of Journal Club?