Last March, international researchers from the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization (BICEP2) telescope at the South Pole claimed that they detected primordial “B-mode” polarization of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. If confirmed, this would have been an incredibly important discovery for astrophysics, as it would constitute evidence of gravitational waves due to cosmic inflation in the first moments of the universe. Nevertheless, as often happens in science, the situation turns out to be more complicated than it initially appeared.

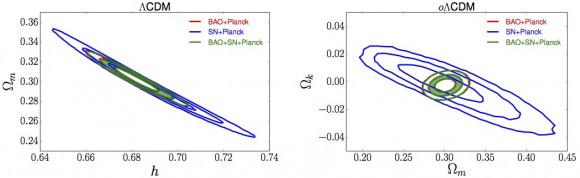

In a joint analysis of data from BICEP2/Keck Array in the South Pole and the space-based Planck telescope, scientists from both collaborations now have a more complete picture and argue that the interpretation of the evidence is muddier than they had previously thought. Their paper will appear in the arXiv pre-print server in a few days and is submitted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters. [Update: the paper is now available on the arXiv.] The European Space Agency issued a press release about the paper on Friday after a summary of it was leaked and briefly posted on a French website.

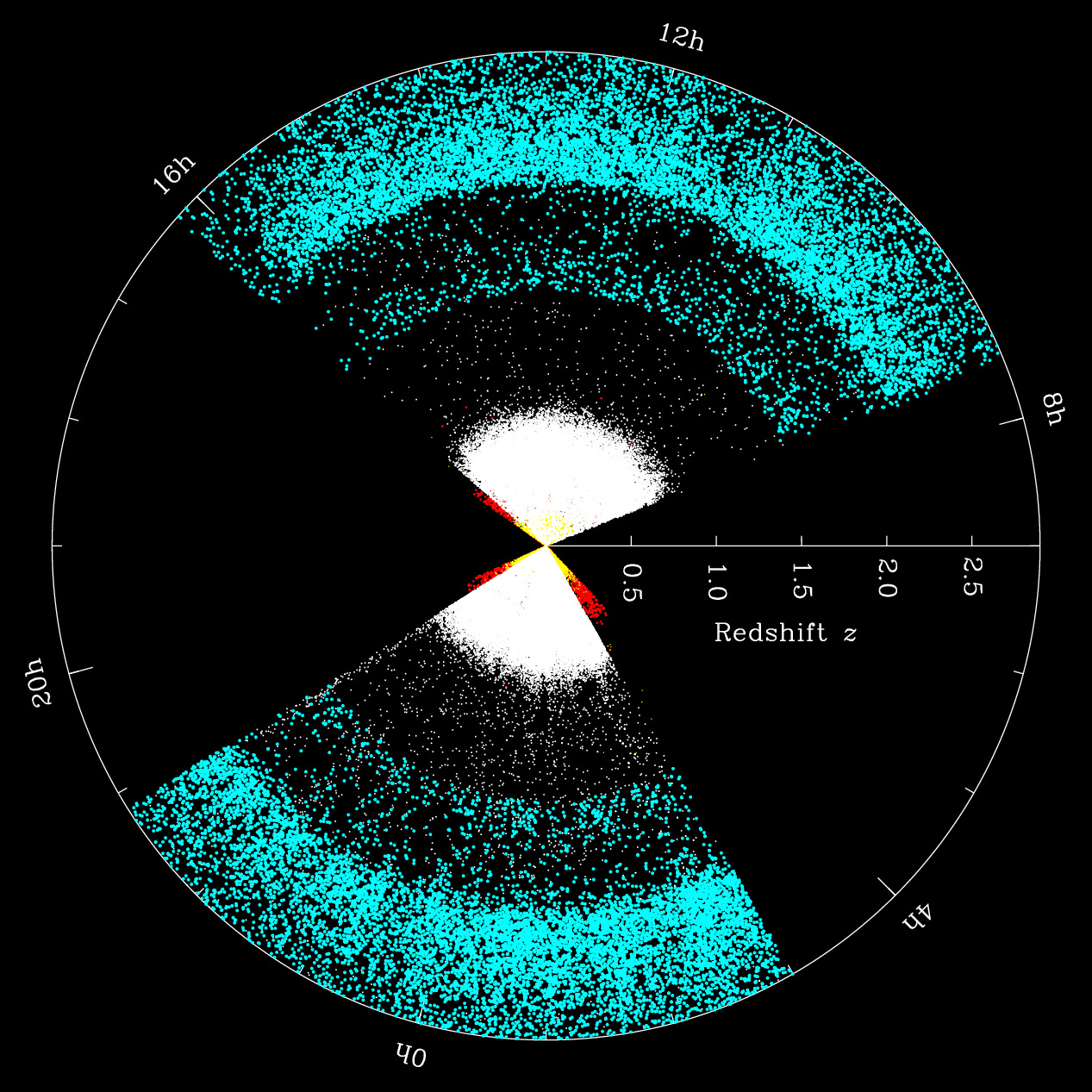

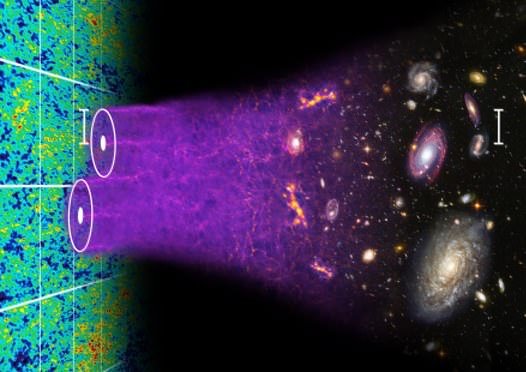

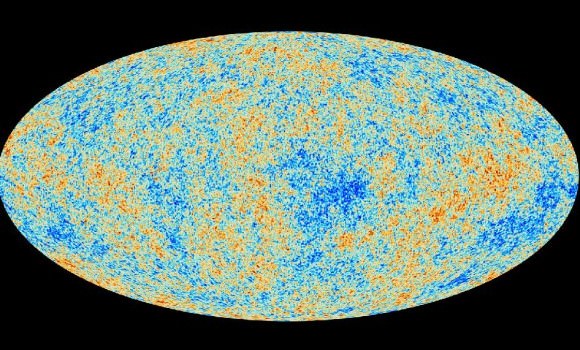

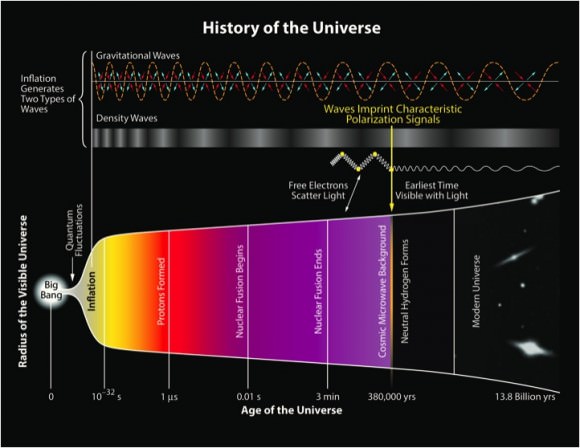

According to inflationary theory, the universe expanded for a brief period at an exponential rate 10-36 seconds after the Big Bang. As a result, models of inflation predict that this rapid acceleration would create ripples in space, generating gravitational waves that would remain energetic enough to leave an imprint on the last-scattered photons, the CMB radiation, approximately 380,000 years later. The CMB spectrum, the “afterglow of the hot Big Bang,” has rich structure in it and has been measured to a “ridiculous level of precision,” according to Professor Martin White (University of California, Berkeley), who gave a plenary talk on cosmology results from Planck at the recent American Astronomical Society meeting.

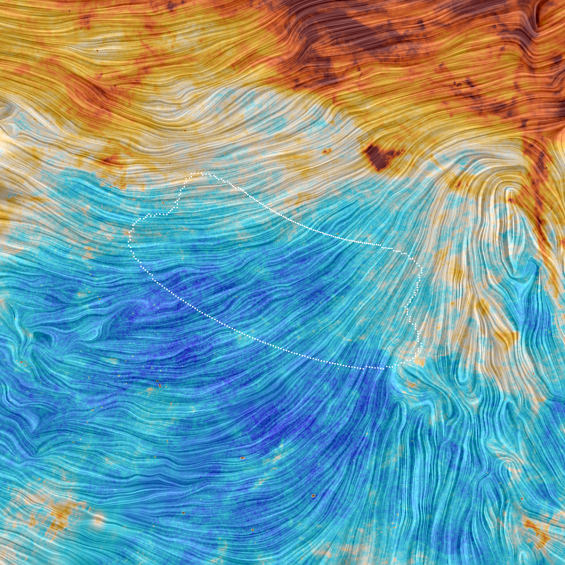

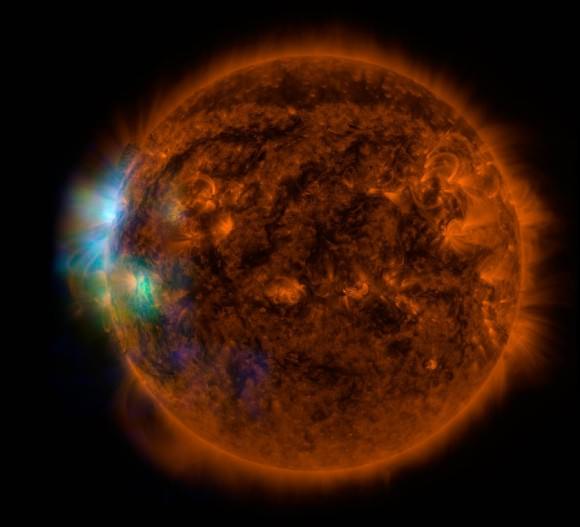

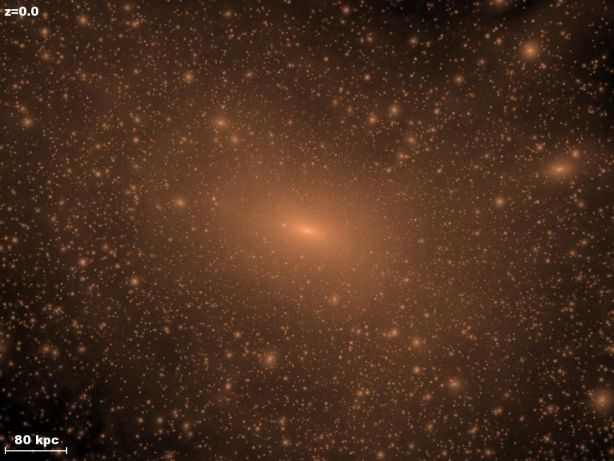

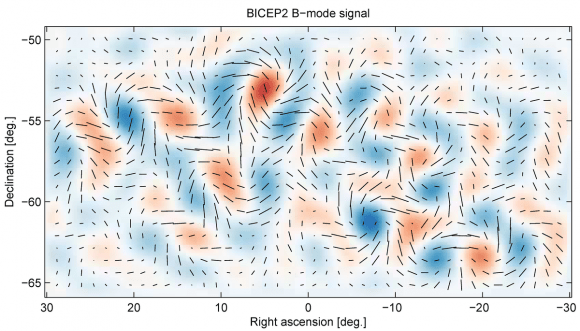

The twists in the polarization signal of the CMB, known as B-modes (shown below) and quantified by a nonzero tensor-to-scalar ratio r, would be evidence in favor of inflation but they are much more difficult to detect. Scientists are trying to decipher a signal on the level of parts per trillion of ambient temperature, mere fractions of a nano-degree! Since inflation would explain why the universe appears to have no overall curvature, why it approximately appears the same in all directions, and why it has structures of galaxies in it, BICEP2’s result last year—the first claimed detection of cosmic inflation—excited physicists around the world. But last summer, Planck scientists presented a map of polarized light from interstellar dust grains and argued that the polarization signal BICEP2 detected could be due to “foreground” dust in our own Milky Way galaxy rather than due to primordial gravitational waves in the distant universe. The hotly debated controversy remained unresolved and led to the new joint analysis by scientists from both teams.

BICEP2 is sensitive to low frequencies (150 GHz) while Planck is more sensitive to higher ones (353 GHz). As Professor Brian Keating (University of California, San Diego), a member of the BICEP2 collaboration, puts it, “it’s as if you’re listening to an opera, but BICEP2 could only hear the tenors and Planck could only hear the sopranos.” Unfortunately, the joint analysis produced only an upper limit to the value of r, meaning that the evidence for B-mode polarization due to inflation remains elusive for now. “It’s probably at best an admixture of Milky Way dust and gravitational waves,” says Keating. [Full disclosure: until last year, Ramin Skibba was a research scientist in the same department but in a different field as Keating at UC San Diego.]

This result must seem disappointing to BICEP2 scientists, but science often works this way, especially for such a difficult phenomenon to study. The signal is strong, but the interpretation is more complicated than it first appeared. On a positive note, the analysis shows that CMB researchers are faced with a foreground challenge rather than one due to the Earth’s atmosphere or to their detectors.

Although Planck will have additional polarization measurements and more assessments of systematic uncertainties in a later data release, they will not be able to settle this debate for now. But new experiments will come online soon, including a BICEP3, and they will produce more precise measurements that could effectively remove the contribution from dust. The signal is tractable, and scientists are looking forward to the day when they can declare with strong statistical significance that they have finally discovered evidence of inflation.