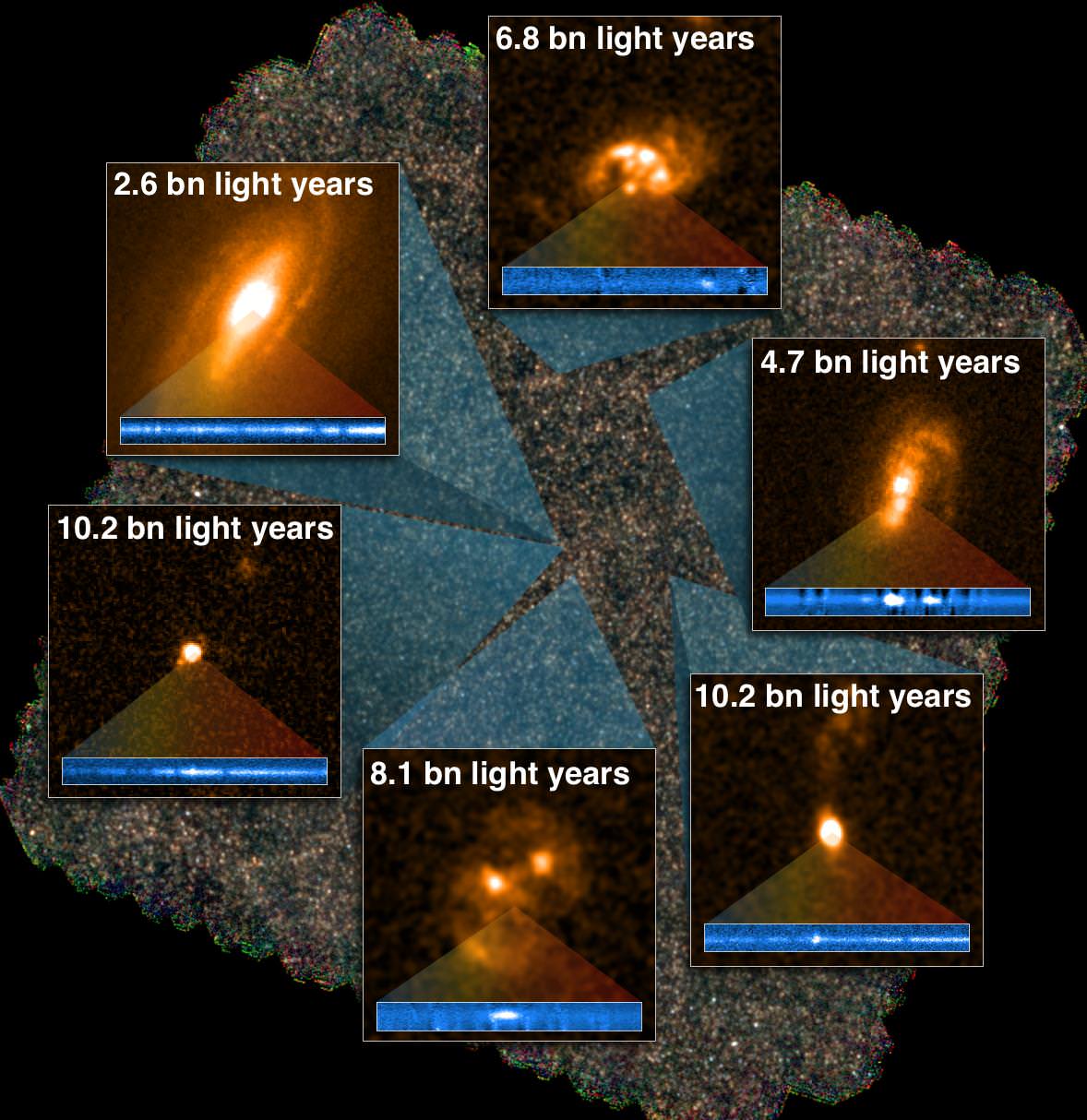

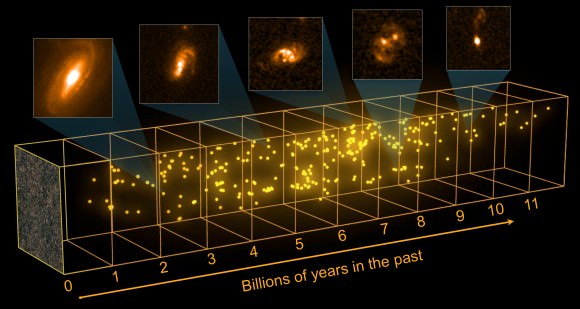

Behind every modern tale of cosmological discovery is the supercomputer that made it possible. Such was the case with the announcement yesterday from the European Space Agencies’ Planck mission team which raised the age estimate for the universe to 13.82 billion years and tweaked the parameters for the amounts dark matter, dark energy and plain old baryonic matter in the universe.

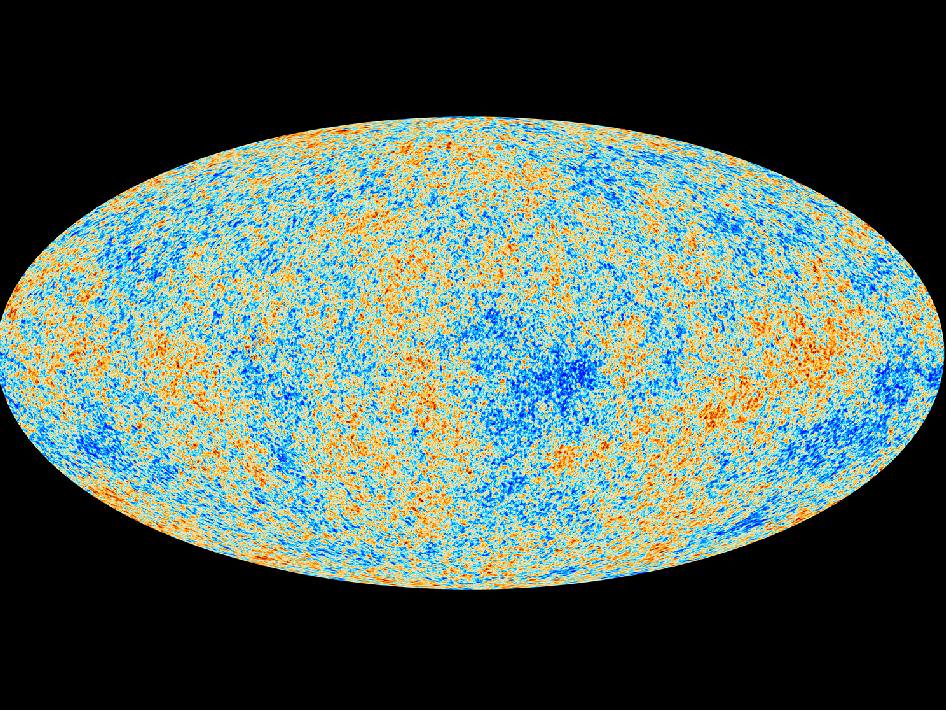

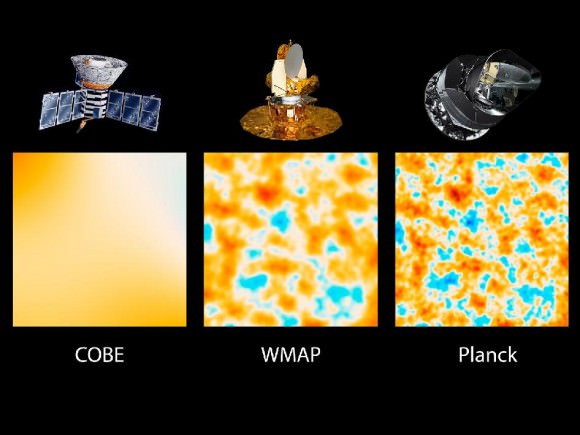

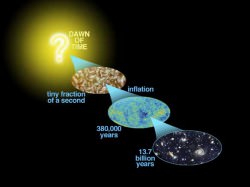

Planck built upon our understanding of the early universe by providing us the most detailed picture yet of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the “fossil relic” of the Big Bang first discovered by Penzias & Wilson in 1965. Planck’s discoveries built upon the CMB map of the universe observed by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and serves to further validate the Big Bang theory of cosmology.

But studying the tiny fluctuations in the faint cosmic microwave background isn’t easy, and that’s where Hopper comes in. From its L2 Lagrange vantage point beyond Earth’s Moon, Planck’s 72 onboard detectors observe the sky at 9 separate frequencies, completing a full scan of the sky every six months. This first release of data is the culmination of 15 months worth of observations representing close to a trillion overall samples. Planck records on average of 10,000 samples every second and scans every point in the sky about 1,000 times.

That’s a challenge to analyze, even for a supercomputer. Hopper is a Cray XE6 supercomputer based at the Department of Energy’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing center (NERSC) at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. Named after computer scientist and pioneer Grace Hopper, the supercomputer has a whopping 217 terabytes of memory running across 153,216 computer cores with a peak performance of 1.28 petaflops a second. Hopper placed number five on a November 2010 list of the world’s top supercomputers. (The Tianhe-1A supercomputer at the National Supercomputing Center in Tianjin China was number one at a peak performance of 4.7 petaflops per second).

One of the main challenges for the team sifting through the flood of CMB data generated by Planck was to filter out the “noise” and bias from the detectors themselves.

“It’s like more than just bugs on a windshield that we want to remove to see the light, but a storm of bugs all around us in every direction,” said Planck project scientist Charles Lawrence. To overcome this, Hopper runs simulations of how the sky would appear to Planck under different conditions and compares these simulations against observations to tease out data.

“By scaling up to tens of thousands of processors, we’ve reduced the time it takes to run these calculations from an impossible 1,000 years to a few weeks,” said Berkeley lab and Planck scientist Ted Kisner.

But the Planck mission isn’t the only data that Hopper is involved with. Hopper and NERSC were also involved with last year’s discovery of the final neutrino mixing angle. Hopper is also currently involved with studying wave-plasma interactions, fusion plasmas and more. You can see the projects that NERSC computers are tasked with currently on their site along with CPU core hours used in real time. Maybe a future descendant of Hopper could give Deep Thought of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame competition in solving the answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything.

Also, a big congrats to Planck and NERSC researchers. Yesterday was a great day to be a cosmologist. At very least, perhaps folks won’t continue to confuse the field with cosmetology… trust us, you don’t want a cosmologist styling your hair!