[/caption]

From a University of Buffalo press release:

Did the early universe have just one spatial dimension? That’s the mind-boggling concept at the heart of a theory that physicist Dejan Stojkovic from the University at Buffalo and colleagues proposed in 2010. They suggested that the early universe — which exploded from a single point and was very, very small at first — was one-dimensional (like a straight line) before expanding to include two dimensions (like a plane) and then three (like the world in which we live today).

The theory, if valid, would address important problems in particle physics.

Now, in a new paper in Physical Review Letters, Stojkovic and Loyola Marymount University physicist Jonas Mureika describe a test that could prove or disprove the “vanishing dimensions” hypothesis.

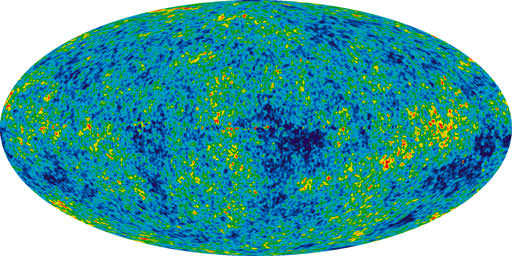

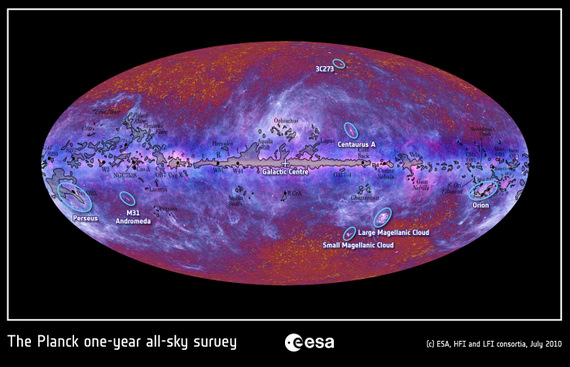

Because it takes time for light and other waves to travel to Earth, telescopes peering out into space can, essentially, look back into time as they probe the universe’s outer reaches.

Gravitational waves can’t exist in one- or two-dimensional space. So Stojkovic and Mureika have reasoned that the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a planned international gravitational observatory, should not detect any gravitational waves emanating from the lower-dimensional epochs of the early universe.

Stojkovic, an assistant professor of physics, says the theory of evolving dimensions represents a radical shift from the way we think about the cosmos — about how our universe came to be.

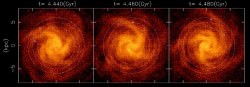

The core idea is that the dimensionality of space depends on the size of the space we’re observing, with smaller spaces associated with fewer dimensions. That means that a fourth dimension will open up — if it hasn’t already — as the universe continues to expand.

The theory also suggests that space has fewer dimensions at very high energies of the kind associated with the early, post-big bang universe.

If Stojkovic and his colleagues are right, they will be helping to address fundamental problems with the standard model of particle physics, including the following:

The incompatibility between quantum mechanics and general relativity. Quantum mechanics and general relativity are mathematical frameworks that describe the physics of the universe. Quantum mechanics is good at describing the universe at very small scales, while relativity is good at describing the universe at large scales. Currently, the two theories are considered incompatible; but if the universe, at its smallest levels, had fewer dimensions, mathematical discrepancies between the two frameworks would disappear.

Physicists have observed that the expansion of the universe is speeding up, and they don’t know why. The addition of new dimensions as the universe grows would explain this acceleration. (Stojkovic says a fourth dimension may have already opened at large, cosmological scales.)

The standard model of particle physics predicts the existence of an as yet undiscovered elementary particle called the Higgs boson. For equations in the standard model to accurately describe the observed physics of the real world, however, researchers must artificially adjust the mass of the Higgs boson for interactions between particles that take place at high energies. If space has fewer dimensions at high energies, the need for this kind of “tuning” disappears.

“What we’re proposing here is a shift in paradigm,” Stojkovic said. “Physicists have struggled with the same problems for 10, 20, 30 years, and straight-forward extensions of the existing ideas are unlikely to solve them.”

“We have to take into account the possibility that something is systematically wrong with our ideas,” he continued. “We need something radical and new, and this is something radical and new.”

Because the planned deployment of LISA is still years away, it may be a long time before Stojkovic and his colleagues are able to test their ideas this way.

However, some experimental evidence already points to the possible existence of lower-dimensional space.

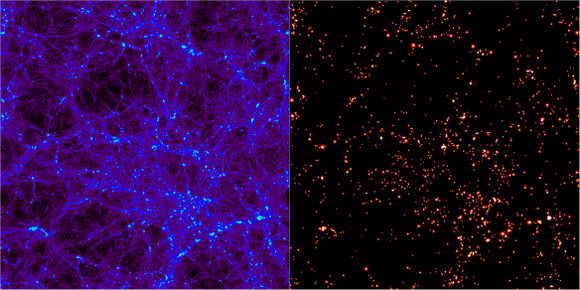

Specifically, scientists have observed that the main energy flux of cosmic ray particles with energies exceeding 1 teraelectron volt — the kind of high energy associated with the very early universe — are aligned along a two-dimensional plane.

If high energies do correspond with lower-dimensional space, as the “vanishing dimensions” theory proposes, researchers working with the Large Hadron Collider particle accelerator in Europe should see planar scattering at such energies.

Stojkovic says the observation of such events would be “a very exciting, independent test of our proposed ideas.”

Sources: EurekAlert, Physical Review Letters.