[/caption]

Cosmologists – and not particle physicists — could be the ones who finally measure the mass of the elusive neutrino particle. A group of cosmologists have made their most accurate measurement yet of the mass of these mysterious so-called “ghost particles.” They didn’t use a giant particle detector but used data from the largest survey ever of galaxies, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. While previous experiments had shown that neutrinos have a mass, it is thought to be so small that it was very hard to measure. But looking at the Sloan data on galaxies, PhD student Shawn Thomas and his advisers at University College London put the mass of a neutrino at no greater than 0.28 electron volts, which is less than a billionth of the mass of a single hydrogen atom. This is one of the most accurate measurements of the mass of a neutrino to date.

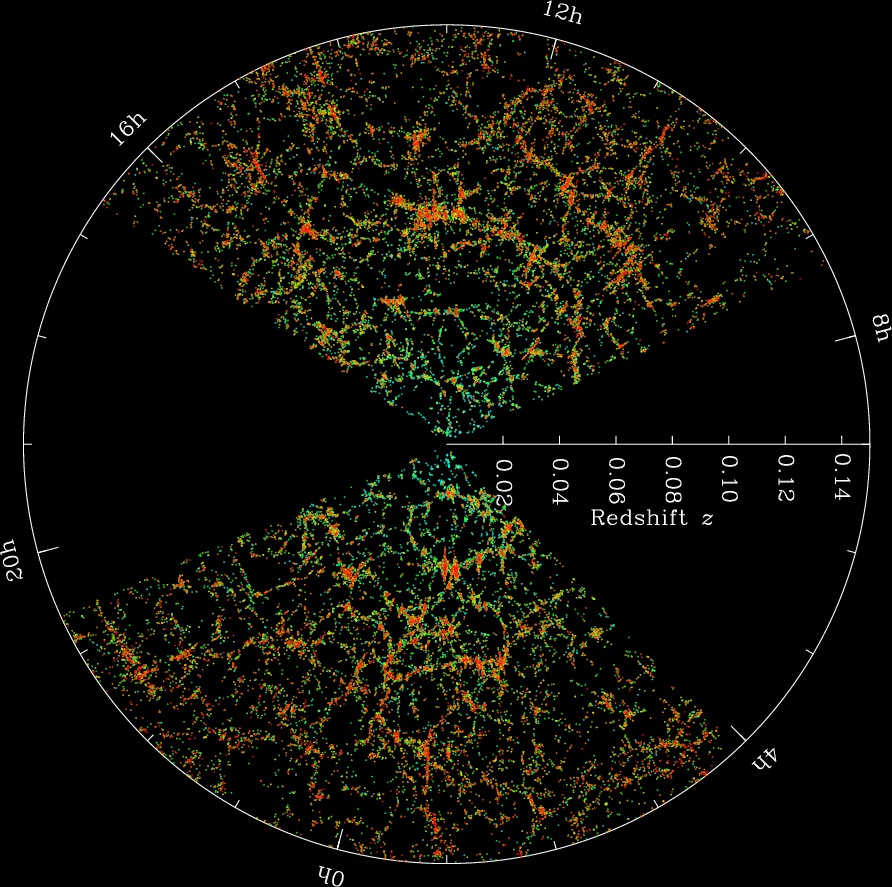

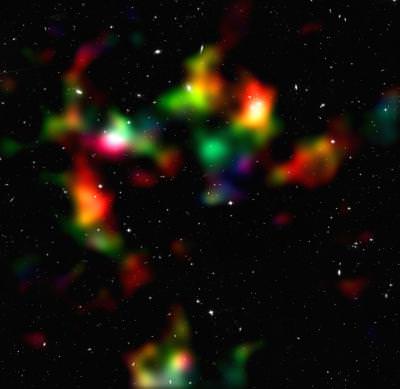

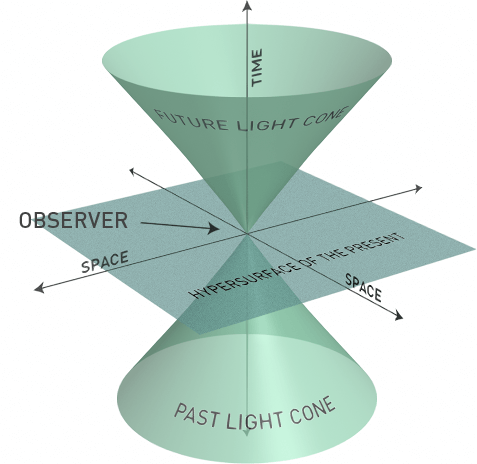

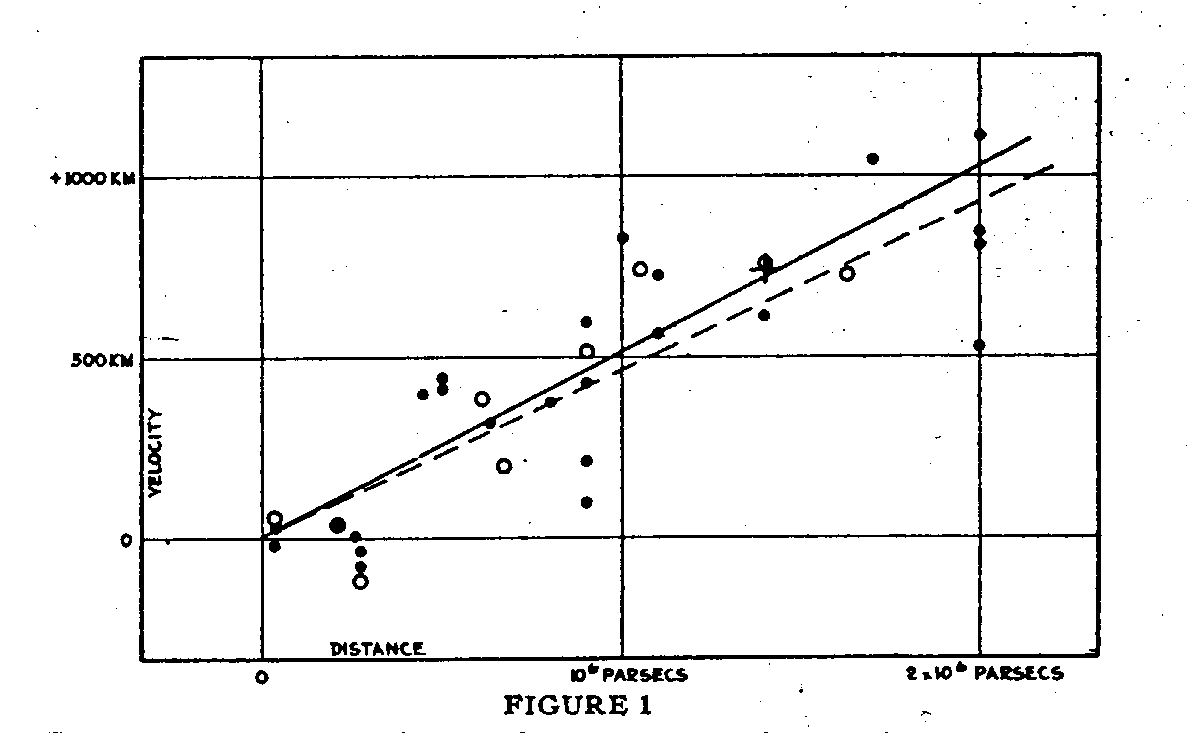

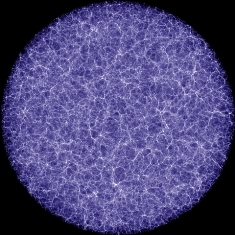

Their work is based on the principle that the huge abundance of neutrinos (there are trillions passing through you right now) has a large cumulative effect on the matter of the cosmos, which naturally forms into “clumps” of groups and clusters of galaxies. As neutrinos are extremely light they move across the universe at great speeds which has the effect of smoothing this natural “clumpiness” of matter. By analysing the distribution of galaxies across the universe (i.e. the extent of this “smoothing-out” of galaxies) scientists are able to work out the upper limits of neutrino mass.

A neutrino is capable of passing through a light year –about six trillion miles — of lead without hitting a single atom.

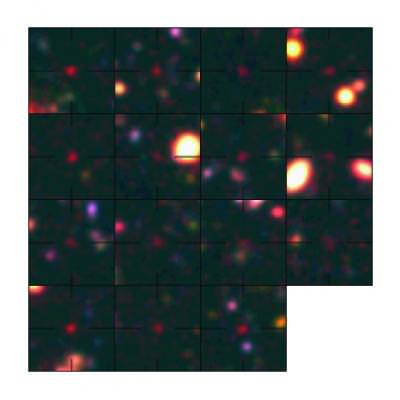

Central to this new calculation is the existence of the largest ever 3D map of galaxies, called Mega Z, which covers over 700,000 galaxies recorded by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and allows measurements over vast stretches of the known universe.

“Of all the hypothetical candidates for the mysterious Dark Matter, so far neutrinos provide the only example of dark matter that actually exists in nature,” said Ofer Lahav, Head of UCL’s Astrophysics Group. “It is remarkable that the distribution of galaxies on huge scales can tell us about the mass of the tiny neutrinos.”

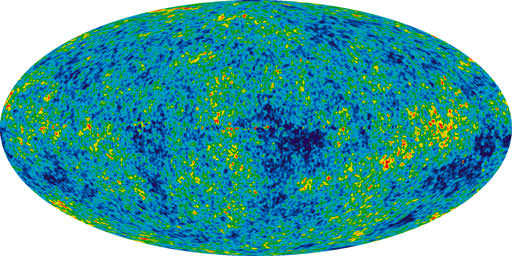

The Cosmologists at UCL were able to estimate distances to galaxies using a new method that measures the colour of each of the galaxies. By combining this enormous galaxy map with information from the temperature fluctuations in the after-glow of the Big Bang, called the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation, they were able to put one of the smallest upper limits on the size of the neutrino particle to date.

“Although neutrinos make up less than 1% of all matter they form an important part of the cosmological model,” said Dr. Shaun Thomas. “It’s fascinating that the most elusive and tiny particles can have such an effect on the Universe.”

“This is one of the most effective techniques available for measuring the neutrino masses,” said Dr. Filipe Abadlla. “This puts great hopes to finally obtain a measurement of the mass of the neutrino in years to come.”

The authors are confident that a larger survey of the Universe, such as the one they are working on called the international Dark Energy Survey, will yield an even more accurate weight for the neutrino, potentially at an upper limit of just 0.1 electron volts.

The results are published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Source: University College London