Since ancient times, philosophers and scholars have sought to understand light. In addition to trying to discern its basic properties (i.e. what is it made of – particle or wave, etc.) they have also sought to make finite measurements of how fast it travels. Since the late-17th century, scientists have been doing just that, and with increasing accuracy.

In so doing, they have gained a better understanding of light’s mechanics and the important role it plays in physics, astronomy and cosmology. Put simply, light moves at incredible speeds and is the fastest moving thing in the Universe. Its speed is considered a constant and an unbreakable barrier, and is used as a means of measuring distance. But just how fast does it travel?

Speed of Light (c):

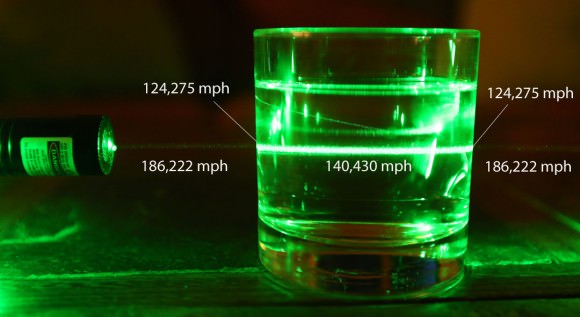

Light travels at a constant speed of 1,079,252,848.8 (1.07 billion) km per hour. That works out to 299,792,458 m/s, or about 670,616,629 mph (miles per hour). To put that in perspective, if you could travel at the speed of light, you would be able to circumnavigate the globe approximately seven and a half times in one second. Meanwhile, a person flying at an average speed of about 800 km/h (500 mph), would take over 50 hours to circle the planet just once.

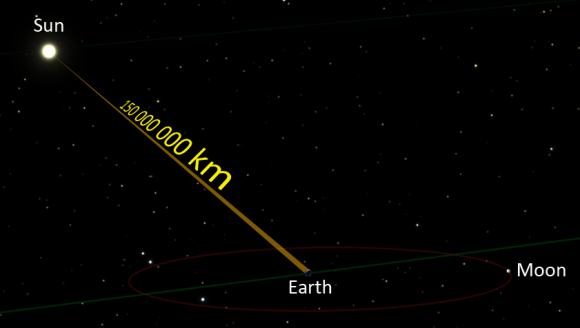

To put that into an astronomical perspective, the average distance from the Earth to the Moon is 384,398.25 km (238,854 miles ). So light crosses that distance in about a second. Meanwhile, the average distance from the Sun to the Earth is ~149,597,886 km (92,955,817 miles), which means that light only takes about 8 minutes to make that journey.

Little wonder then why the speed of light is the metric used to determine astronomical distances. When we say a star like Proxima Centauri is 4.25 light years away, we are saying that it would take – traveling at a constant speed of 1.07 billion km per hour (670,616,629 mph) – about 4 years and 3 months to get there. But just how did we arrive at this highly specific measurement for “light-speed”?

History of Study:

Until the 17th century, scholars were unsure whether light traveled at a finite speed or instantaneously. From the days of the ancient Greeks to medieval Islamic scholars and scientists of the early modern period, the debate went back and forth. It was not until the work of Danish astronomer Øle Rømer (1644-1710) that the first quantitative measurement was made.

In 1676, Rømer observed that the periods of Jupiter’s innermost moon Io appeared to be shorter when the Earth was approaching Jupiter than when it was receding from it. From this, he concluded that light travels at a finite speed, and estimated that it takes about 22 minutes to cross the diameter of Earth’s orbit.

Christiaan Huygens used this estimate and combined it with an estimate of the diameter of the Earth’s orbit to obtain an estimate of 220,000 km/s. Isaac Newton also spoke about Rømer’s calculations in his seminal work Opticks (1706). Adjusting for the distance between the Earth and the Sun, he calculated that it would take light seven or eight minutes to travel from one to the other. In both cases, they were off by a relatively small margin.

Later measurements made by French physicists Hippolyte Fizeau (1819 – 1896) and Léon Foucault (1819 – 1868) refined these measurements further – resulting in a value of 315,000 km/s (192,625 mi/s). And by the latter half of the 19th century, scientists became aware of the connection between light and electromagnetism.

This was accomplished by physicists measuring electromagnetic and electrostatic charges, who then found that the numerical value was very close to the speed of light (as measured by Fizeau). Based on his own work, which showed that electromagnetic waves propagate in empty space, German physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber proposed that light was an electromagnetic wave.

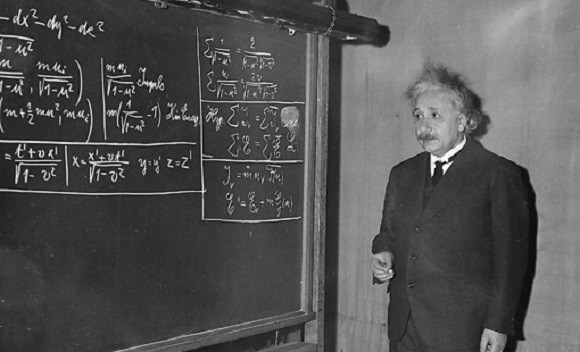

The next great breakthrough came during the early 20th century/ In his 1905 paper, titled “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies”, Albert Einstein asserted that the speed of light in a vacuum, measured by a non-accelerating observer, is the same in all inertial reference frames and independent of the motion of the source or observer.

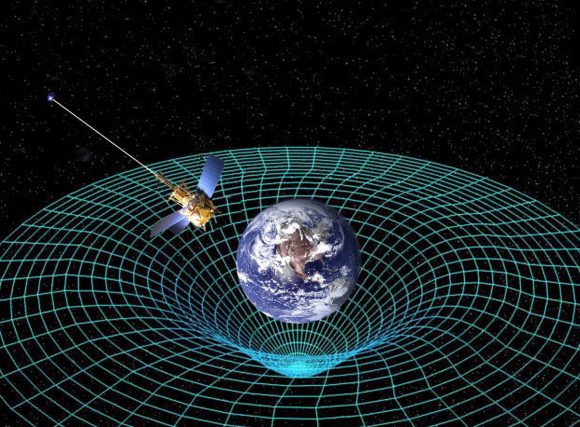

Using this and Galileo’s principle of relativity as a basis, Einstein derived the Theory of Special Relativity, in which the speed of light in vacuum (c) was a fundamental constant. Prior to this, the working consensus among scientists held that space was filled with a “luminiferous aether” that was responsible for its propagation – i.e. that light traveling through a moving medium would be dragged along by the medium.

This in turn meant that the measured speed of the light would be a simple sum of its speed through the medium plus the speed of that medium. However, Einstein’s theory effectively made the concept of the stationary aether useless and revolutionized the concepts of space and time.

Not only did it advance the idea that the speed of light is the same in all inertial reference frames, it also introduced the idea that major changes occur when things move close the speed of light. These include the time-space frame of a moving body appearing to slow down and contract in the direction of motion when measured in the frame of the observer (i.e. time dilation, where time slows as the speed of light approaches).

His observations also reconciled Maxwell’s equations for electricity and magnetism with the laws of mechanics, simplified the mathematical calculations by doing away with extraneous explanations used by other scientists, and accorded with the directly observed speed of light.

During the second half of the 20th century, increasingly accurate measurements using laser inferometers and cavity resonance techniques would further refine estimates of the speed of light. By 1972, a group at the US National Bureau of Standards in Boulder, Colorado, used the laser inferometer technique to get the currently-recognized value of 299,792,458 m/s.

Role in Modern Astrophysics:

Einstein’s theory that the speed of light in vacuum is independent of the motion of the source and the inertial reference frame of the observer has since been consistently confirmed by many experiments. It also sets an upper limit on the speeds at which all massless particles and waves (which includes light) can travel in a vacuum.

One of the outgrowths of this is that cosmologists now treat space and time as a single, unified structure known as spacetime – in which the speed of light can be used to define values for both (i.e. “lightyears”, “light minutes”, and “light seconds”). The measurement of the speed of light has also become a major factor when determining the rate of cosmic expansion.

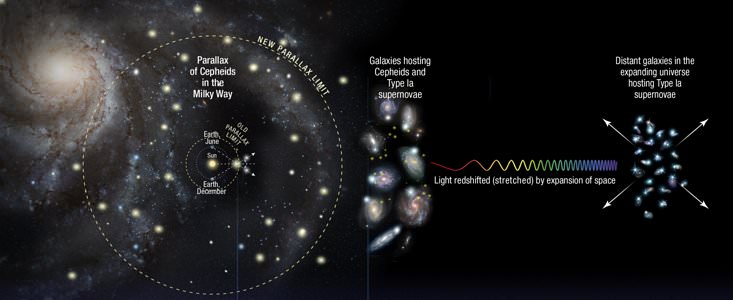

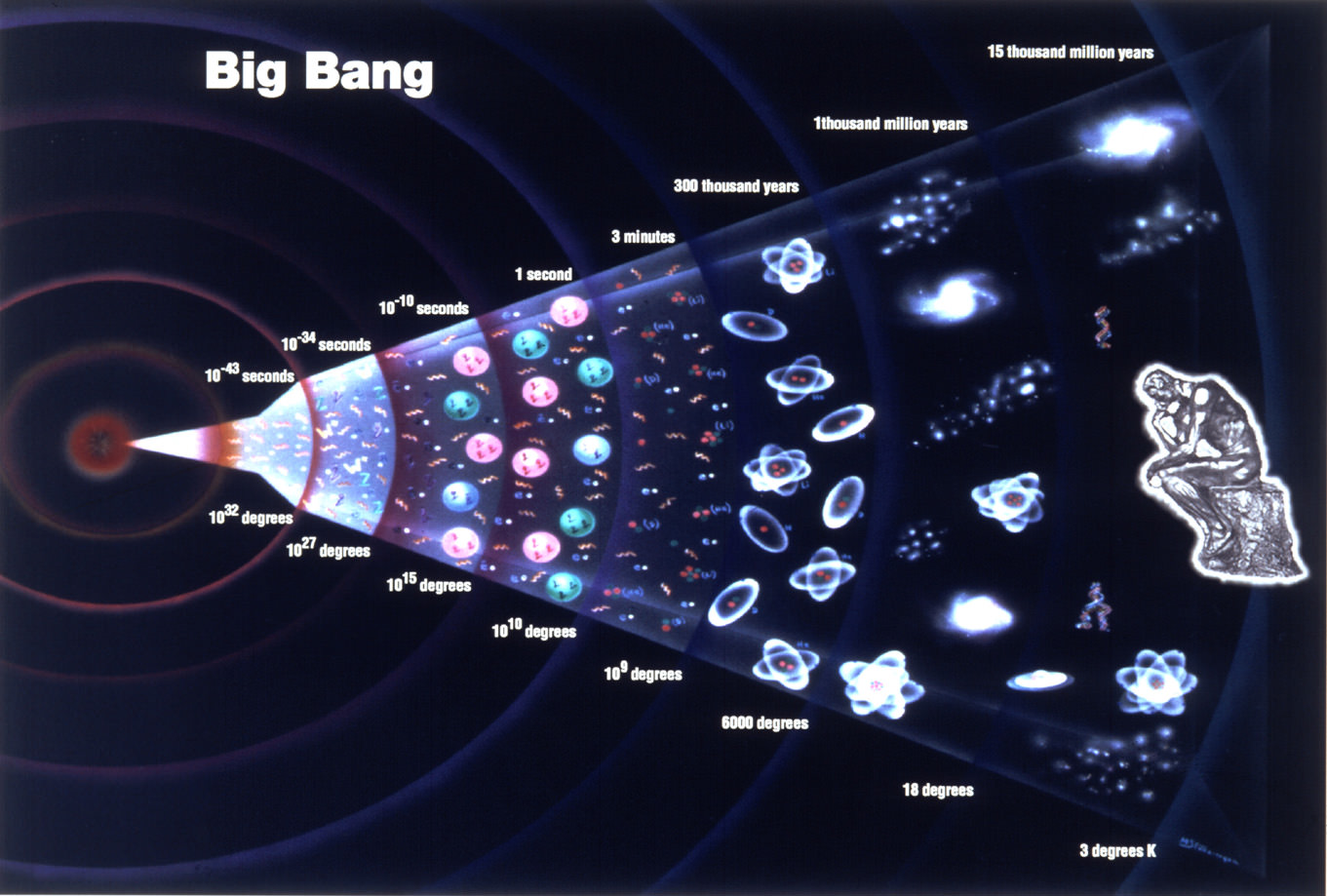

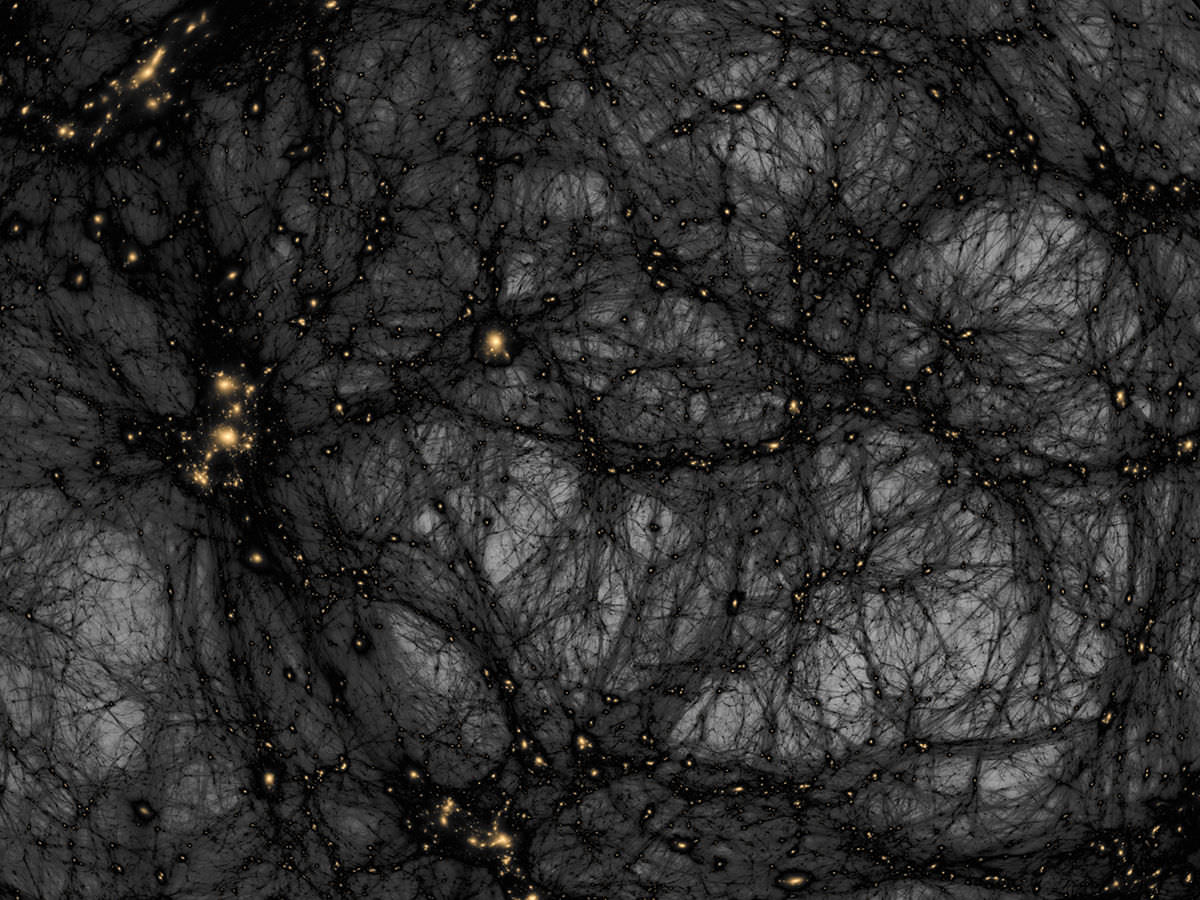

Beginning in the 1920’s with observations of Lemaitre and Hubble, scientists and astronomers became aware that the Universe is expanding from a point of origin. Hubble also observed that the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it appears to be moving. In what is now referred to as the Hubble Parameter, the speed at which the Universe is expanding is calculated to 68 km/s per megaparsec.

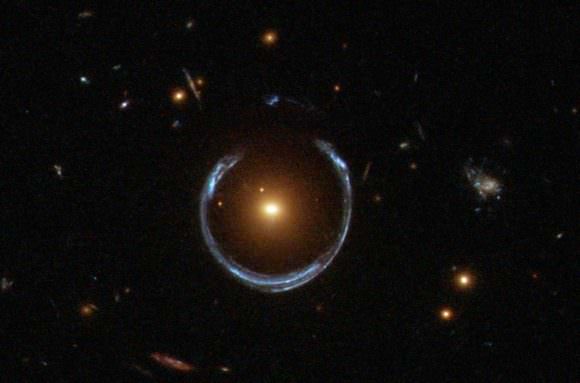

This phenomena, which has been theorized to mean that some galaxies could actually be moving faster than the speed of light, may place a limit on what is observable in our Universe. Essentially, galaxies traveling faster than the speed of light would cross a “cosmological event horizon”, where they are no longer visible to us.

Also, by the 1990’s, redshift measurements of distant galaxies showed that the expansion of the Universe has been accelerating for the past few billion years. This has led to theories like “Dark Energy“, where an unseen force is driving the expansion of space itself instead of objects moving through it (thus not placing constraints on the speed of light or violating relativity).

Along with special and general relativity, the modern value of the speed of light in a vacuum has gone on to inform cosmology, quantum physics, and the Standard Model of particle physics. It remains a constant when talking about the upper limit at which massless particles can travel, and remains an unachievable barrier for particles that have mass.

Perhaps, someday, we will find a way to exceed the speed of light. While we have no practical ideas for how this might happen, the smart money seems to be on technologies that will allow us to circumvent the laws of spacetime, either by creating warp bubbles (aka. the Alcubierre Warp Drive), or tunneling through it (aka. wormholes).

Until that time, we will just have to be satisfied with the Universe we can see, and to stick to exploring the part of it that is reachable using conventional methods.

We have written many articles about the speed of light for Universe Today. Here’s How Fast is the Speed of Light?, How are Galaxies Moving Away Faster than Light?, How Can Space Travel Faster than the Speed of Light?, and Breaking the Speed of Light.

Here’s a cool calculator that lets you convert many different units for the speed of light, and here’s a relativity calculator, in case you wanted to travel nearly the speed of light.

Astronomy Cast also has an episode that addresses questions about the speed of light – Questions Show: Relativity, Relativity, and more Relativity.

Sources: