By Matthew Williams

March 15, 2025

Earlier this week, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) announced the science objectives for the fourth cycle of the James Webb Space Telescope's (JWST) General Observations program - aka. Cycle 4 GO. In keeping with Webb's major science objectives, many of these programs will focus on the study of the earliest galaxies in the Universe.

Continue reading

By Andy Tomaswick

March 15, 2025

Ingenuity proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that a helicopter can operate on another planet. Over 72 flights, the little quadcopter that could captivated the imagination of space exploration fans everywhere. But, several factors limited it, and researchers at NASA think they can do better. Two papers presented at the recent Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, held March 10-14 in The Woodlands, Texas, and led by Pascal Lee of NASA Ames and Derric Loya of the SETI Institute and Colorado Mesa University, describe a use case for that still-under-development helicopter, which they call Nighthawk.

Continue reading

By Carolyn Collins Petersen

March 14, 2025

Exploration of the outer Solar System may be getting a boost from the Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO). When this gigantic telescope opens its eye later in 2025, it begins a decade-long survey of the ever-changing sky. As part of this time-lapse vision of the cosmos, distant objects in the Kuiper Belt will be among its most challenging targets.

Continue reading

By Andy Tomaswick

March 14, 2025

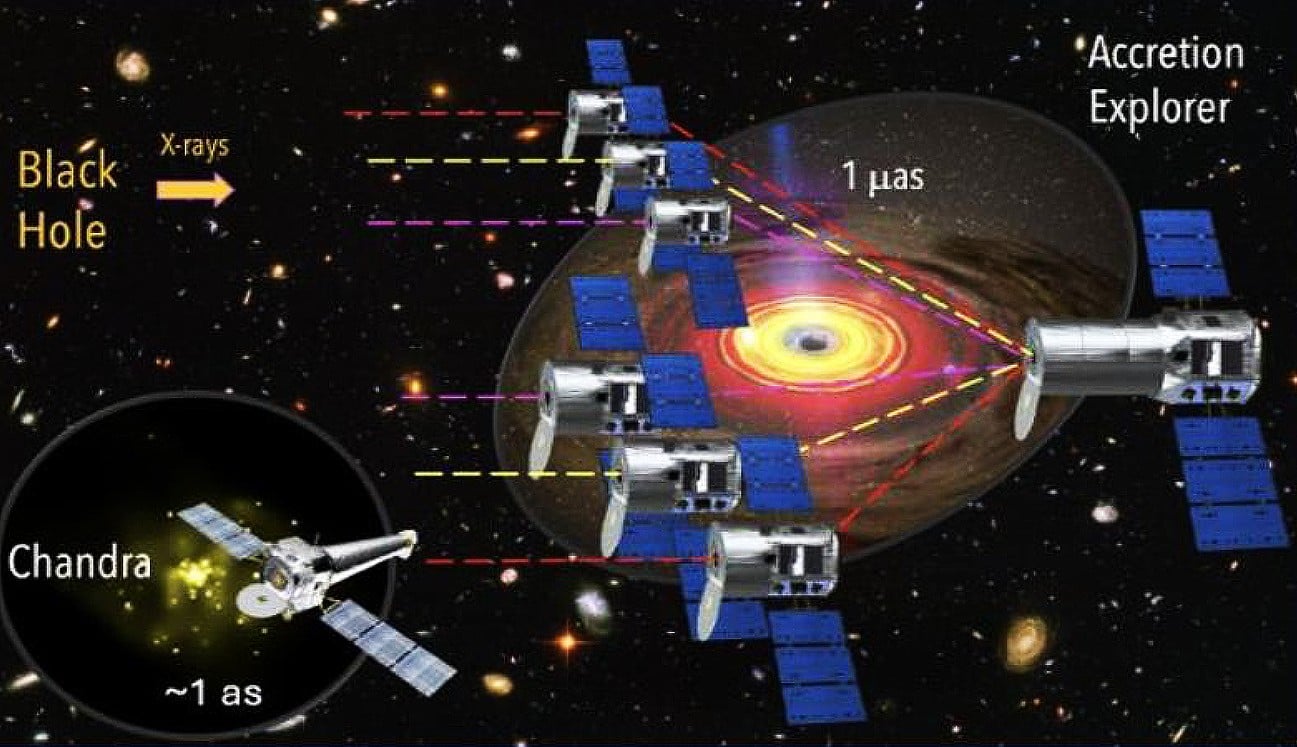

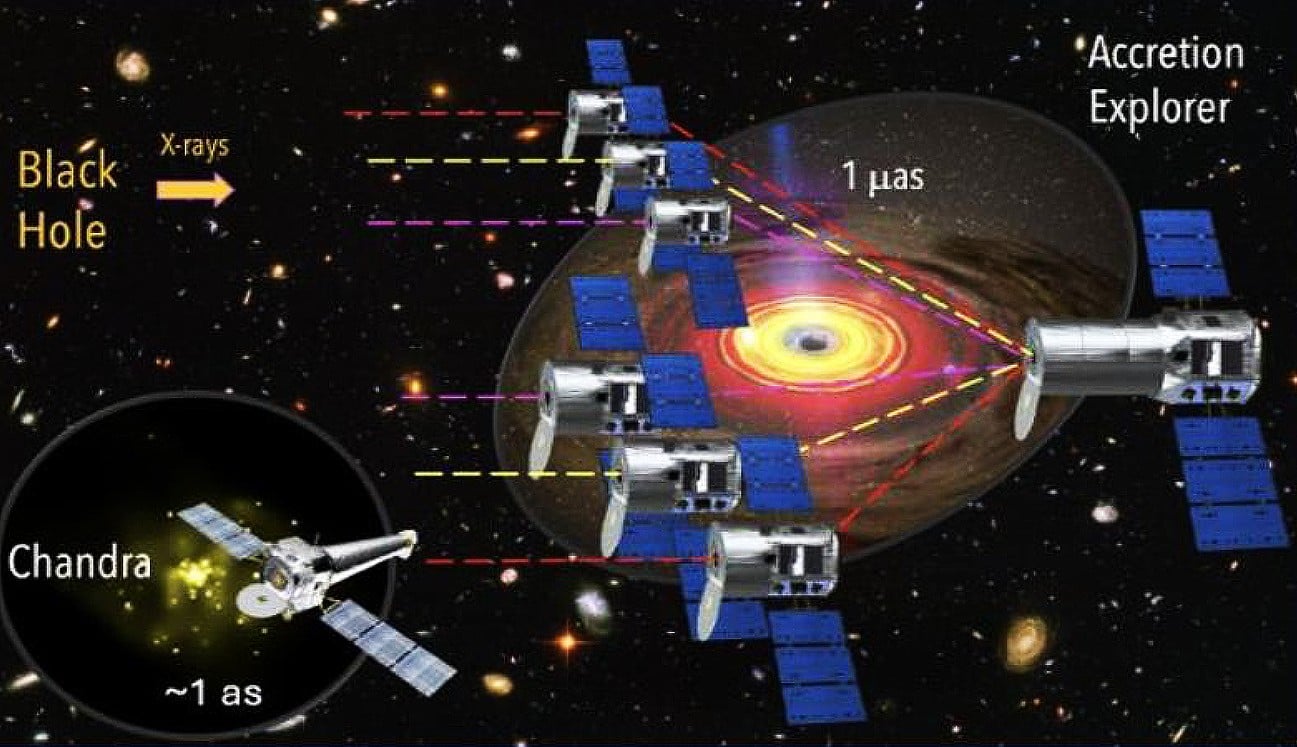

X-ray astronomy is a somewhat neglected corner of the more general field of astronomy. The biggest names in telescopes, like Hubble and James Webb, don't even touch that bandwidth. And Chandra, the most capable space-based X-ray observatory to date, is far less well-known. However, some of the most interesting phenomena in the universe can only be truly understood through X-rays, and it's a shame that the discipline doesn't garner more attention. Kimberly Weaver of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center hopes to change that perception as she works on a NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) grant to develop an in-space X-ray interferometer that could allow us to see for the first time what causes the power behind supermassive black holes.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 14, 2025

Thursday brought with it a total lunar eclipse for parts of the world that could see the Moon. If you missed it (like I did) then no problem since Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost mission has got your back. The lunar lander took a break from its science duties on our nearest astronomical neighbour to capture this stunning image of the eclipse. Observers on Earth saw the shadow of the Earth fall across the Moon but for Blue Ghost, it experienced a solar eclipse where the Sun hid behind the Earth!

Continue reading

By Andy Tomaswick

March 14, 2025

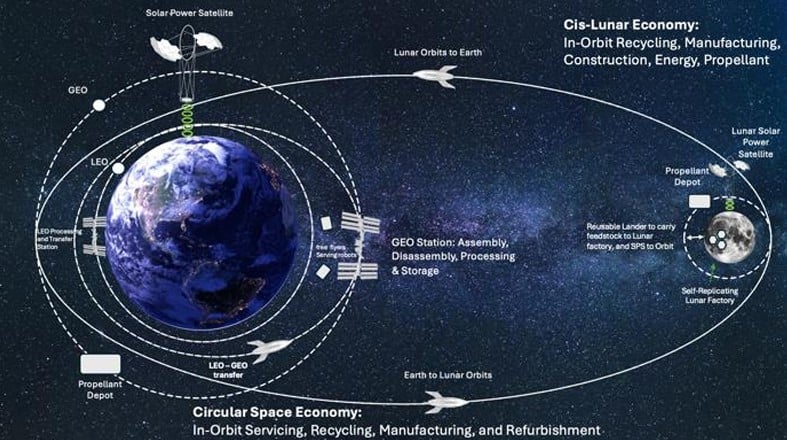

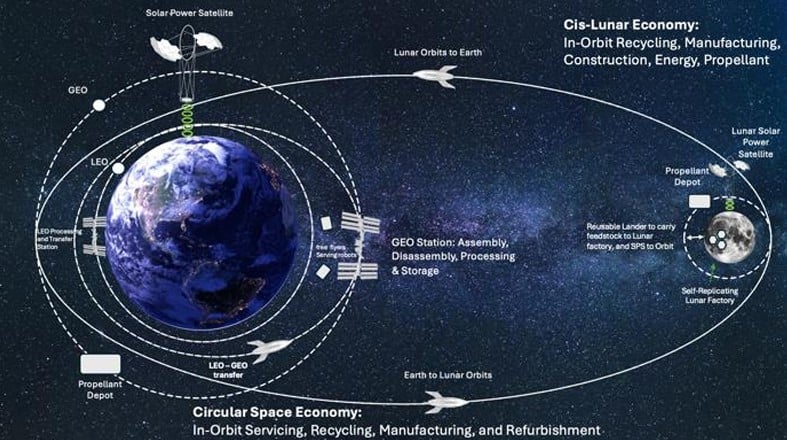

Solar Power Satellite (SPS) advocates have been dreaming of using space resources to build massive constructions for decades. In-space Resource Utilization (ISRU) advocates would love to oblige them, but so far, there hasn't yet been enough development on either front to create a testable system. A research team from a company called MetaSat and the University of Glasgow hope to change that with a new plan called META-LUNA, which utilizes lunar resources to build (and recycle) a fleet of their specially designed SPS.

Continue reading

By Matthew Williams

March 13, 2025

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) has announced the science objectives for Webb's General Observer Programs in Cycle 4 (Cycle 4 GO) program. The Cycle 4 observations include 274 programs that establish the science program for JWST's fourth year of operations, amounting to 8,500 hours of prime observing time. This is a significant increase from Cycle 3 observations and the 5,500 hours of prime time and 1,000 hours of parallel time it entailed.

Continue reading

By David Dickinson

March 13, 2025

A distant trio of worlds may shed light on planetary formation in the early solar system.

Sometimes, good things come in threes. If astronomers are correct, a system in the distant Kuiper Belt may not be two but three worlds, offering an insight into formation in the early solar system.

The study comes out of researchers at Brigham Young University and the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Continue reading

By Mark Thompson

March 13, 2025

The increasing frequency of so-called ‘1-in-a-1000-year' weather events highlights how global warming is disrupting rather more typical weather patterns beyond what scientific models can reliably predict. A recent paper proposes a three-tier scientific approach for addressing these unprecedented climate challenges: improving rapid response capabilities, making incremental infrastructure adaptations, and pursuing transformational system changes to manage escalating climate chaos.

Continue reading

By Evan Gough

March 13, 2025

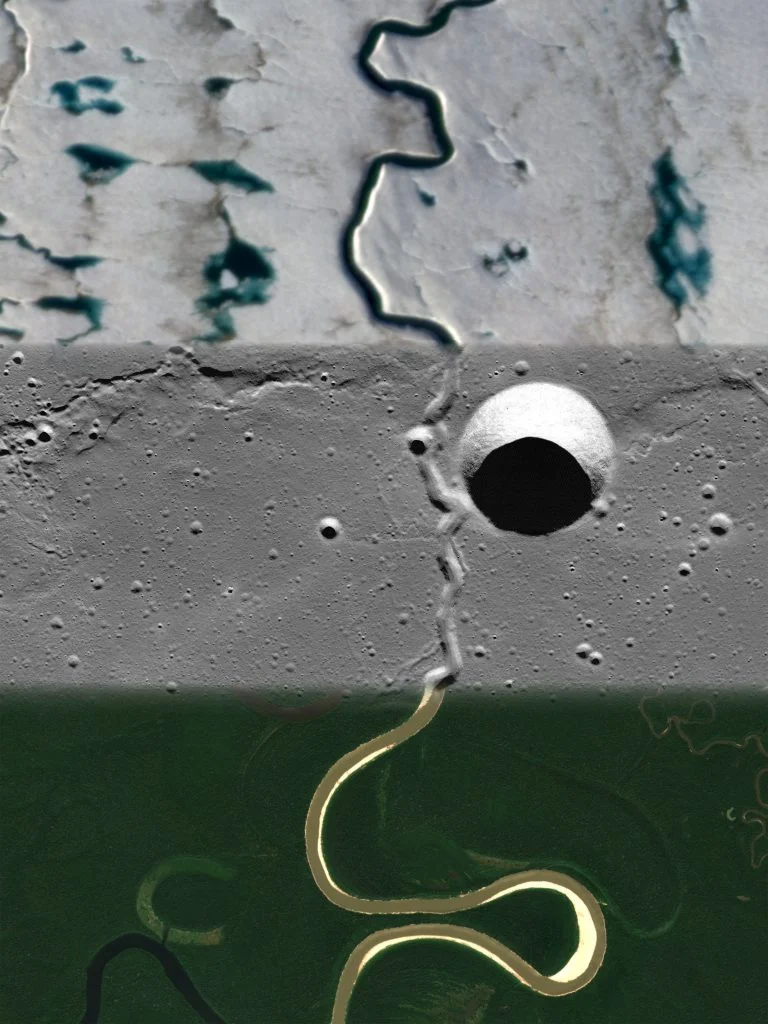

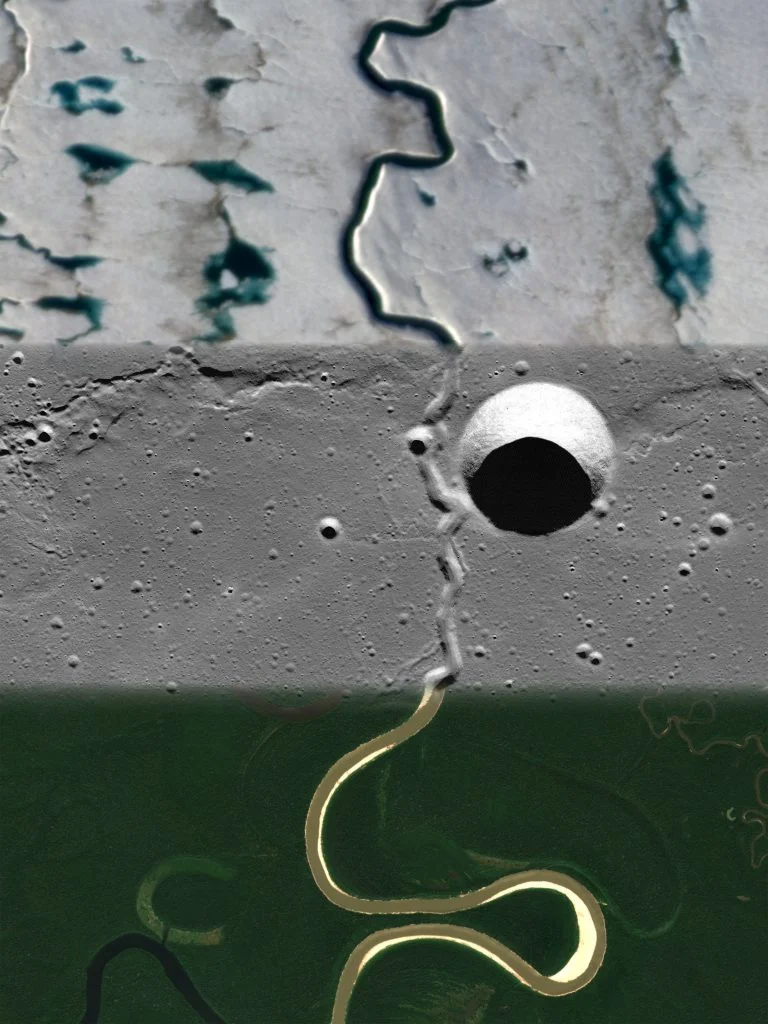

Orbital images of Mars show how water has carved channels into the planet's surface. However, Mars also had a volcanic past when lava carved its own surface channels, confounding scientists' attempts to understand the planet's history. Some channels could also

Continue reading

Universe Today

Universe Today