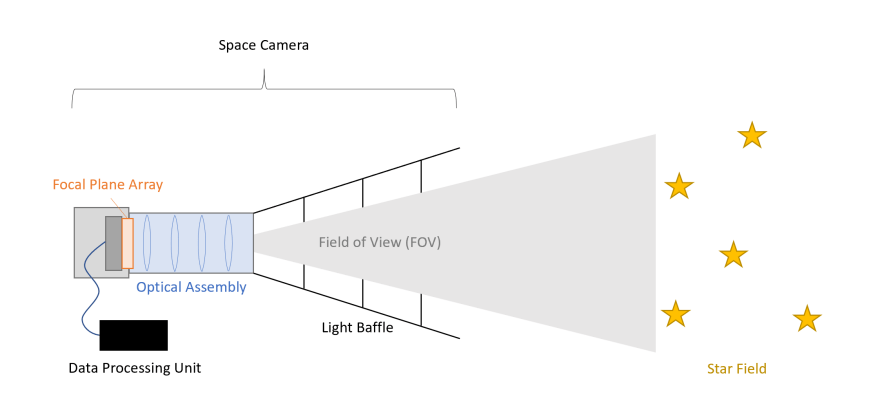

One of the hardest things for many people to conceptualize when talking about how fast something is going is that they must ask, “Compared to what?” All motion only makes sense from a frame of reference, and many spacecraft traveling in the depths of the void lack any regular reference from which to understand how fast they’re going. There have been several different techniques to try to solve this problem, but one of the ones that have been in development the longest is StarNAV – a way to navigate in space using only the stars.

Continue reading “Lost In Space? Just Use Relativity”A Tiny Telescope is Revealing “Hot Jupiter” Secrets

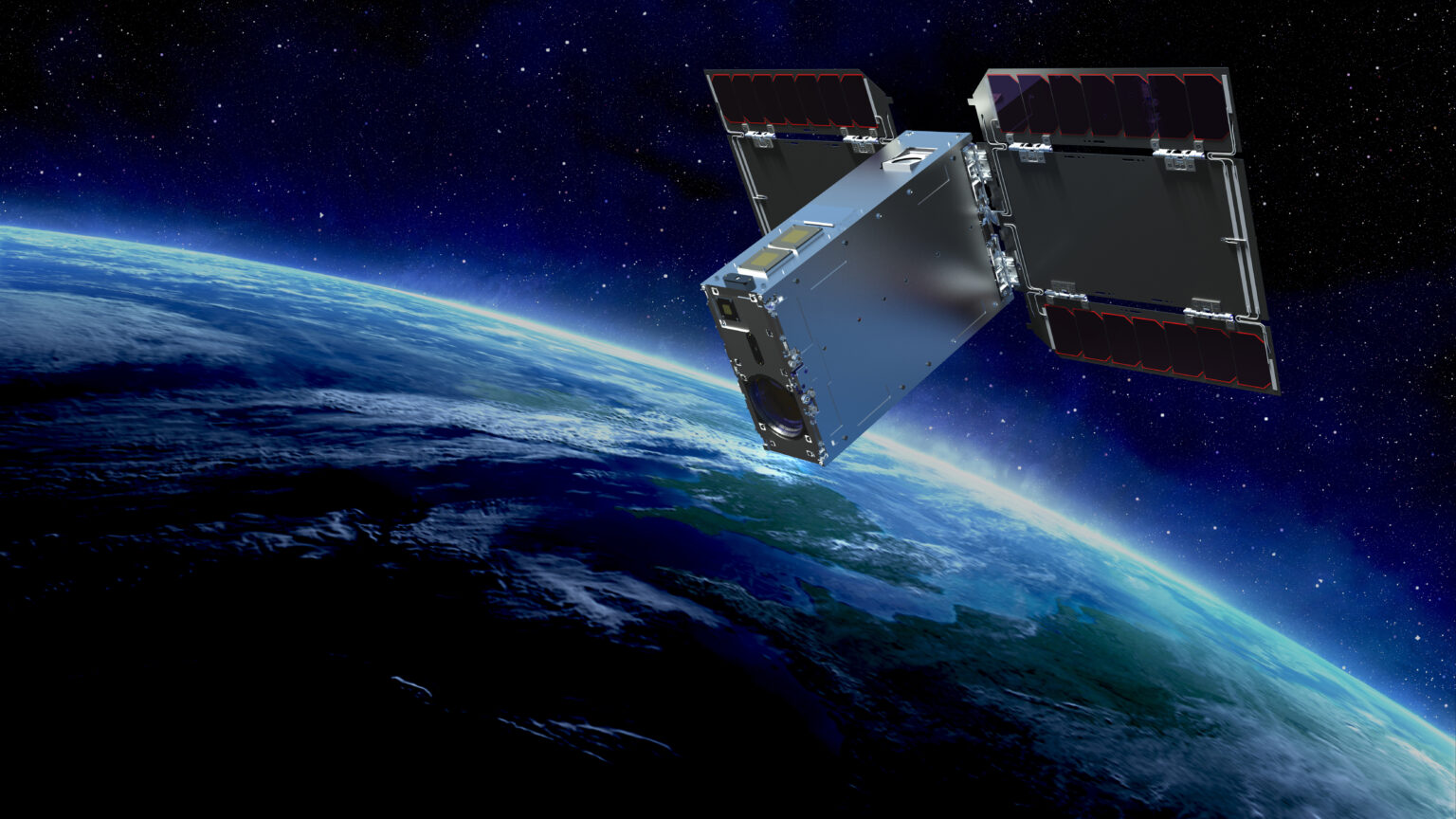

A recent study presented this week at the 2023 meeting of the American Geophysical Union discusses observations of “hot Jupiters” from the NASA-funded CubeSat mission known as the Colorado Ultraviolet Transit Experiment (CUTE). Unlike most exoplanet-hunting telescopes, whose sizes are comparable to a small school bus, CUTE measures 36 centimeters (14 inches) in length, equivalent to the size of a cereal box. These findings come after members of the team, which consists of undergraduate and graduate students, published an overview paper about CUTE in The Astronomical Journal in January 2023 and results from CUTE observing WASP-189b in The Astrophysical Journal Letters in August 2023.

Continue reading “A Tiny Telescope is Revealing “Hot Jupiter” Secrets”Building a Satellite out of Wood? Use Magnolia

Typically when you think of a satellite, you think of a metal box with electronic components inside it. But that is simply because most satellites have been made that way throughout history. There is nothing against using other materials to build satellites. Now, a team of researchers from Japan has completed testing on another type of material that could eventually be used on an actual satellite – magnolia wood.

Continue reading “Building a Satellite out of Wood? Use Magnolia”Pale Blue Successfully Operates its Water-Based Propulsion System in Orbit

New in-space propulsion techniques seem to be popping out of the woodwork. The level of innovation behind moving things around in space is astounding, and now a company from Japan has just hit a significant milestone. Pale Blue, which I assumed was named as a nod to a beloved Carl Sagan book, recently successfully tested their in-orbit water-based propulsion system, adding yet another safe, affordable propulsion system to satellite designers’ repertoires.

Continue reading “Pale Blue Successfully Operates its Water-Based Propulsion System in Orbit”NASA is Testing out new Composite Materials for Building Lightweight Solar Sail Supports

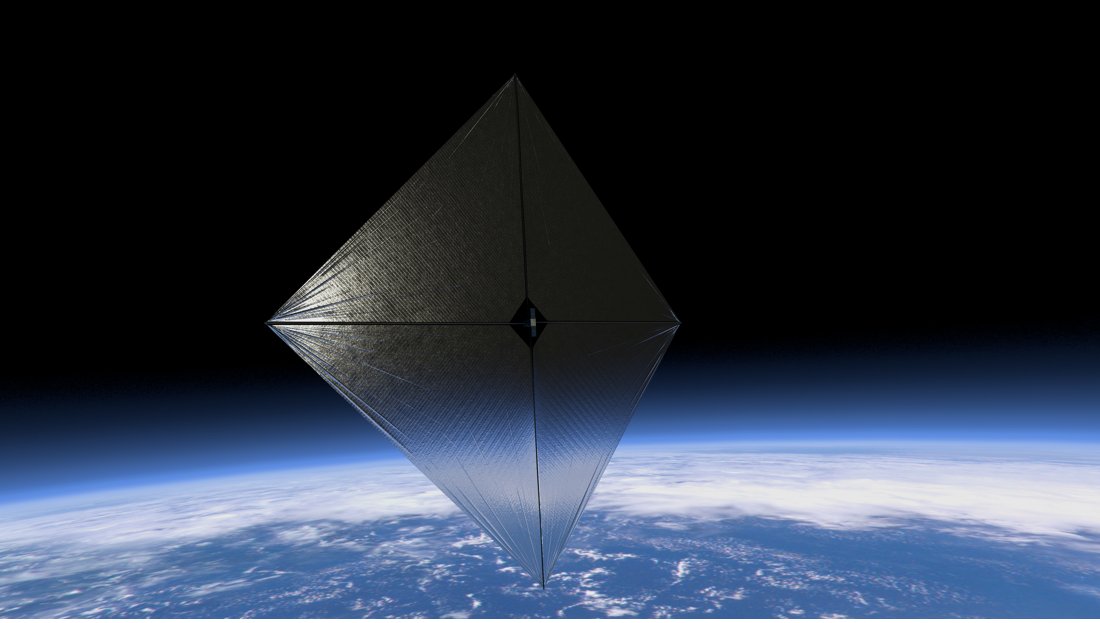

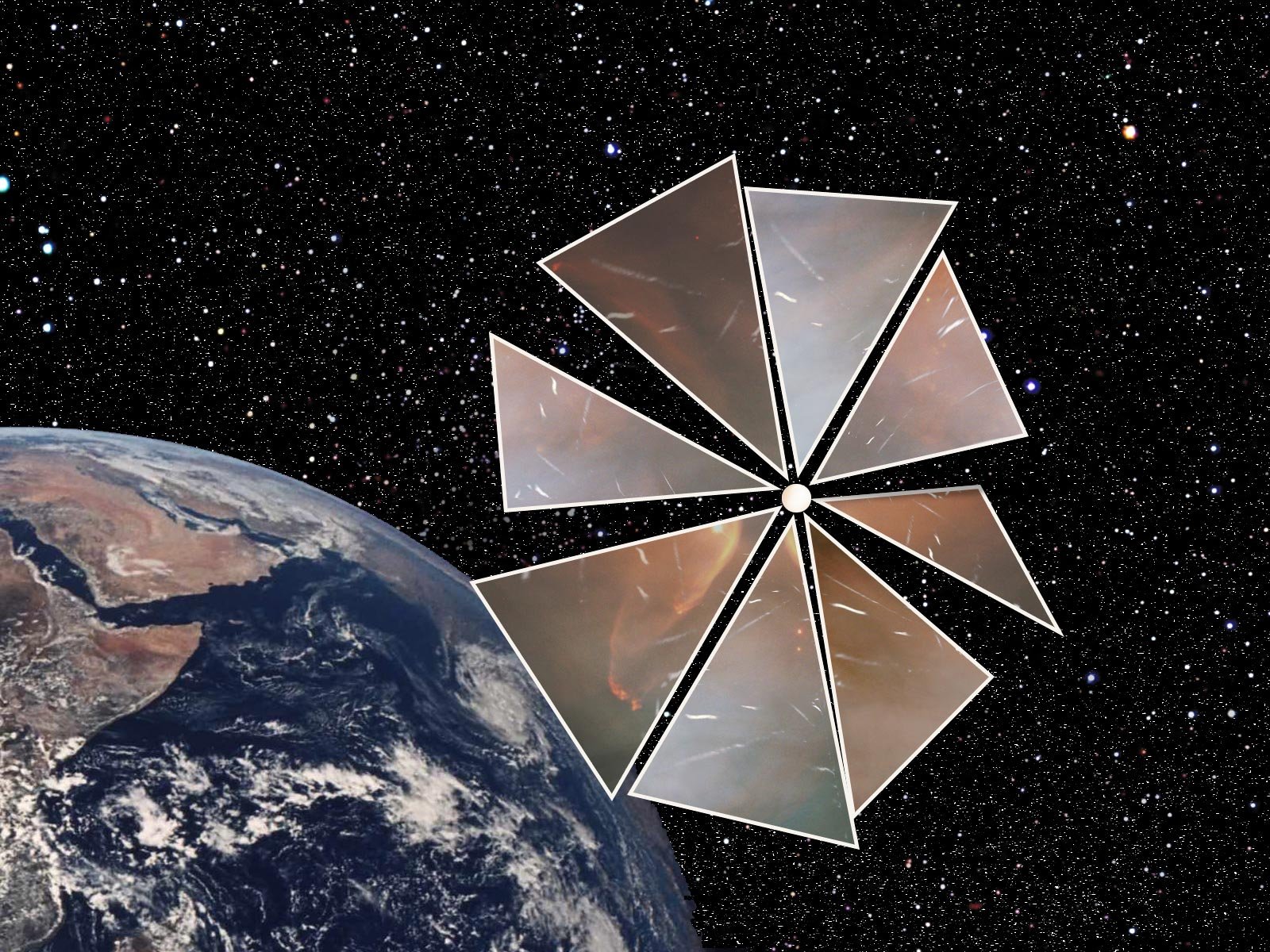

Space exploration is driven by technology – sometimes literally in the case of propulsion technologies. Solar sails are one of those propulsion technologies that has been getting a lot of attention lately. They have some obvious advantages, such as not requiring fuel, and their ability to last almost indefinitely. But they have some disadvantages too, not the least of which is how difficult they are to deploy in space. Now, a team from NASA’s Langley Research Center has developed a novel time of composite boom that they believe can help solve that weakness of solar sails, and they have a technology demonstration mission coming up next year to prove it.

Continue reading “NASA is Testing out new Composite Materials for Building Lightweight Solar Sail Supports”A Small Satellite With a Solar Sail Could Catch up With an Interstellar Object

When Oumuamua, the first interstellar object ever observed passing through the Solar System, was discovered in 2017, it exhibited some unexpected properties that left astronomers scratching their heads. Its elongated shape, lack of a coma, and the fact that it changed its trajectory were all surprising, leading to several competing theories about its origin: was it a hydrogen iceberg exhibiting outgassing, or maybe an extraterrestrial solar sail (sorry folks, not likely) on a deep-space journey? We may never know the answer, because Oumuamua was moving too fast, and was observed too late, to get a good look.

It may be too late for Oumuamua, but we could be ready for the next strange interstellar visitor if we wanted to. A spacecraft could be designed and built to catch such an object at a moment’s notice. The idea of an interstellar interceptor like this has been floated by various experts, and funding to study such a concept has even been granted through NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. But how exactly would such an interceptor work?

Continue reading “A Small Satellite With a Solar Sail Could Catch up With an Interstellar Object”Teeny Tiny Space Telescope has Taken Thousands of Pictures of Both Earth and Space

A new nanosat has been quietly snapping over 4500 pictures of the Earth and the sky after its launch on May 15th. Rocketed into orbit on a Falcon 9, the nanosat, known as GEOStare2, actually contains two different telescopes – one focuses on a wide field of view while the other has a much narrower field of view but much higher resolution. Together they aim to provide data on Earth, the stars, and the network of satellites in between.

Continue reading “Teeny Tiny Space Telescope has Taken Thousands of Pictures of Both Earth and Space”A Cubesat Will Test out Water as a Propulsion System

Novel propulsion systems for CubeSats have been on an innovative tear of late. UT has reported on propulsion systems that use everything from solid iodine to the Earth’s own magnetic field as a way of moving a small spacecraft. Now there is a potential solution using a much more mundane material for a propellant – water.

Continue reading “A Cubesat Will Test out Water as a Propulsion System”The First Cubesat With a Hall-Effect Thruster has Gone to Space

Student-led teams aren’t the only ones testing out novel electric propulsion techniques recently. Back in November, a company called Exotrail successfully tested a completely new kind of electric propulsion system in space – a small hall-effect thruster.

Continue reading “The First Cubesat With a Hall-Effect Thruster has Gone to Space”A New Satellite Is Going to Try to Maintain Low Earth Orbit Without Any Propellant

Staying afloat in space can be deceptively hard. Just ask the characters from Gravity, or any number of the hundreds of small satellites that fall into the atmosphere in a given year. Any object placed in low Earth orbit (LEO) must constantly fight against the drag caused by the small number of air molecules that make it up to that height.

Usually they counteract this force by using small amounts of propellant. However, smaller satellites don’t have the luxury of enough propellant to keep them afloat for any period of time. But now a team of students from the University of Michigan has launched a prototype satellite that attempts to stay afloat using a novel technique – magnetism.

Continue reading “A New Satellite Is Going to Try to Maintain Low Earth Orbit Without Any Propellant”