[/caption]

It used to be the case that if you wanted to send a spacecraft mission out past the asteroid belt, you’d need a chunk of plutonium-238 to generate electric power – like for Pioneers 10 and 11, Voyagers 1 and 2, Galileo, Cassini, even Ulysses which just did a big loop out and back to get a new angle on the Sun – and now New Horizons on its way to Pluto.

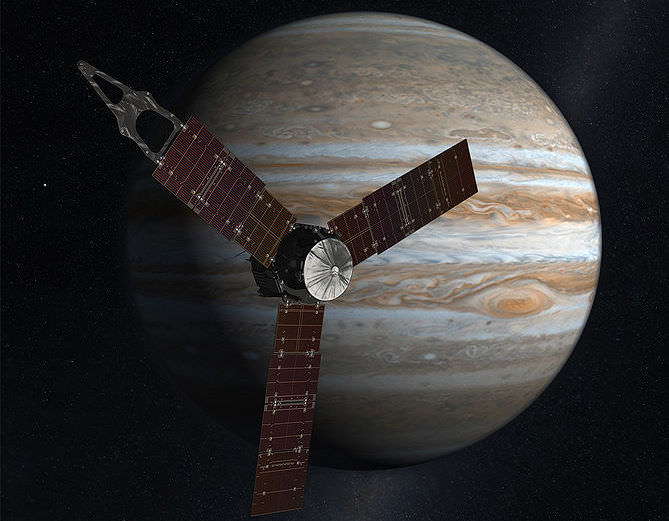

But in 2011, the Juno mission to Jupiter is scheduled for launch – the first outer planet exploration mission to be powered by solar panels. And also scheduled for 2011, in another break with tradition – Curiosity, the Mars Science Laboratory will be the first Mars rover to be powered by a plutonium-238 radioisotope thermoelectric generator – or RTG.

I mean OK, the Viking landers had RTGs, but they weren’t rovers. And the rovers (including Sojourner) had radioisotope heaters, but they weren’t RTGs.

So, solar or RTG – what’s best? Some commentators have suggested that NASA’s decision to power Juno with solar is a pragmatic one – seeking to conserve a dwindling supply of RTGs – which have a bit of a PR problem due to the plutonium.

However, if it works, why not push the limits of solar? Although some of our longest functioning probes (like the 33 year old Voyagers) are RTG powered, their long-term survival is largely a result of them operating far away from the harsh radiation of the inner solar system – where things are more likely to break down before they run out of power. That said, since Juno will lead a perilous life flying close to Jupiter’s own substantial radiation, longevity may not be a key feature of its mission.

Perhaps RTG power has more utility. It should enable Curiosity to go on roving throughout the Martian winter – and perhaps manage a range of analytical, processing and data transmission tasks at night, unlike the previous rovers.

With respect to power output, Juno’s solar panels would allegedly produce a whopping 18 kilowatts in Earth orbit, but will only manage 400 watts in Jupiter orbit. If correct, this is still on par with the output of a standard RTG unit – although a large spacecraft like Cassini can stack several RTG units together to generate up to 1 kilowatt.

So, some pros and cons there. Nonetheless, there is a point – which we might position beyond Jupiter’s orbit now – where solar power just isn’t going to cut it and RTGs still look like the only option.

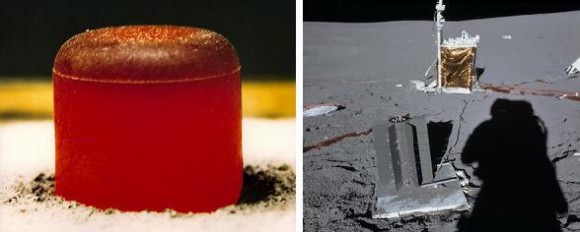

RTGs take advantage of the heat generated by a chunk of radioactive material (generally plutonium 238 in a ceramic form), surrounding it with thermocouples which use the thermal gradient between the heat source and the cooler outer surface of the RTG unit to generate current.

In response to any OMG it’s radioactive concerns, remember that RTGs travelled with the Apollo 12-17 crews to power their lunar surface experiment packages – including the one on Apollo 13 – which was returned unused to Earth with the lunar module Aquarius – the crew’s life boat until just before re-entry. Allegedly, NASA tested the waters where the remains of Aquarius ended up and found no trace of plutonium contamination – much as expected. It’s unlikely that its heat tested container was damaged on re-entry and its integrity was guaranteed for ten plutonium-238 half-lives, that is 900 years.

In any case, the most dangerous thing you can do with plutonium is to concentrate it. In the unlikely event that an RTG disintegrates on Earth re-entry and its plutonium is somehow dispersed across the planet – well, good. The bigger worry would be that it somehow stays together as a pellet and plonks into your beer without you noticing. Cheers.