[/caption]

Now that the old year has drawn to a close, it’s traditional to take stock. And why not think big and take stock of everything there is?

Let’s base our inventory on energy. And as Einstein taught us that energy and mass are equivalent, that means automatically taking stock of all the mass that’s in the universe, as well – including all the different forms of matter we might be interested in.

Of course, since the universe might well be infinite in size, we can’t simply add up all the energy. What we’ll do instead is look at fractions: How much of the energy in the universe is in the form of planets? How much is in the form of stars? How much is plasma, or dark matter, or dark energy?

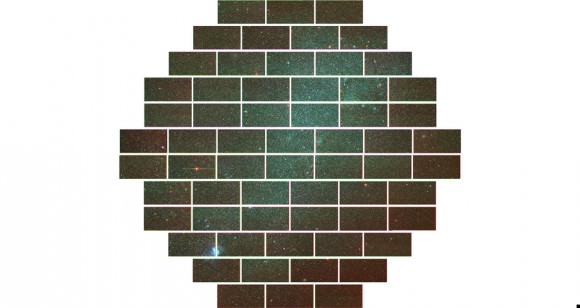

The chart above is a fairly detailed inventory of our universe. The numbers I’ve used are from the article The Cosmic Energy Inventory by Masataka Fukugita and Jim Peebles, published in 2004 in the Astrophysical Journal (vol. 616, p. 643ff.). The chart style is borrowed from Randall Munroe’s Radiation Dose Chart over at xkcd.

These fractions will have changed a lot over time, of course. Around 13.7 billion years ago, in the Big Bang phase, there would have been no stars at all. And the number of, say, neutron stars or stellar black holes will have grown continuously as more and more massive stars have ended their lives, producing these kinds of stellar remnants. For this chart, following Fukugita and Peebles, we’ll look at the present era. What is the current distribution of energy in the universe? Unsurprisingly, the values given in that article come with different uncertainties – after all, the authors are extrapolating to a pretty grand scale! The details can be found in Fukugita & Peebles’ article; for us, their most important conclusion is that the observational data and their theoretical bases are now indeed firm enough for an approximate, but differentiated and consistent picture of the cosmic inventory to emerge.

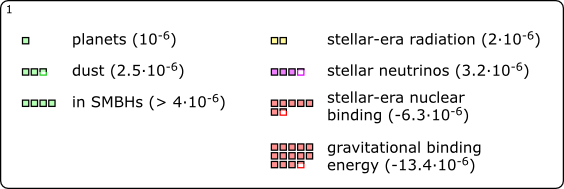

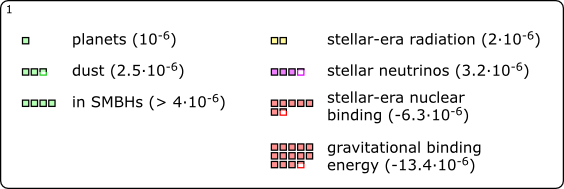

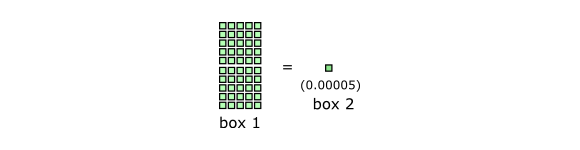

Let’s start with what’s closest to our own home. How much of the energy (equivalently, mass) is in the form of planets? As it turns out: not a lot. Based on extrapolations from what data we have about exoplanets (that is, planets orbiting stars other than the sun), just one part-per-million (1 ppm) of all energy is in the form of planets; in scientific notation: 10-6. Let’s take “1 ppm” as the basic unit for our first chart, and represent it by a small light-green square. (Fractions of 1 ppm will be represented by partially filled such squares.) Here is the first box (of three), listing planets and other contributions of about the same order of magnitude:

So what else is in that box? Other forms of condensed matter, mainly cosmic dust, account for 2.5 ppm, according to rough extrapolations based on observations within our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Among other things, this is the raw material for future planets!

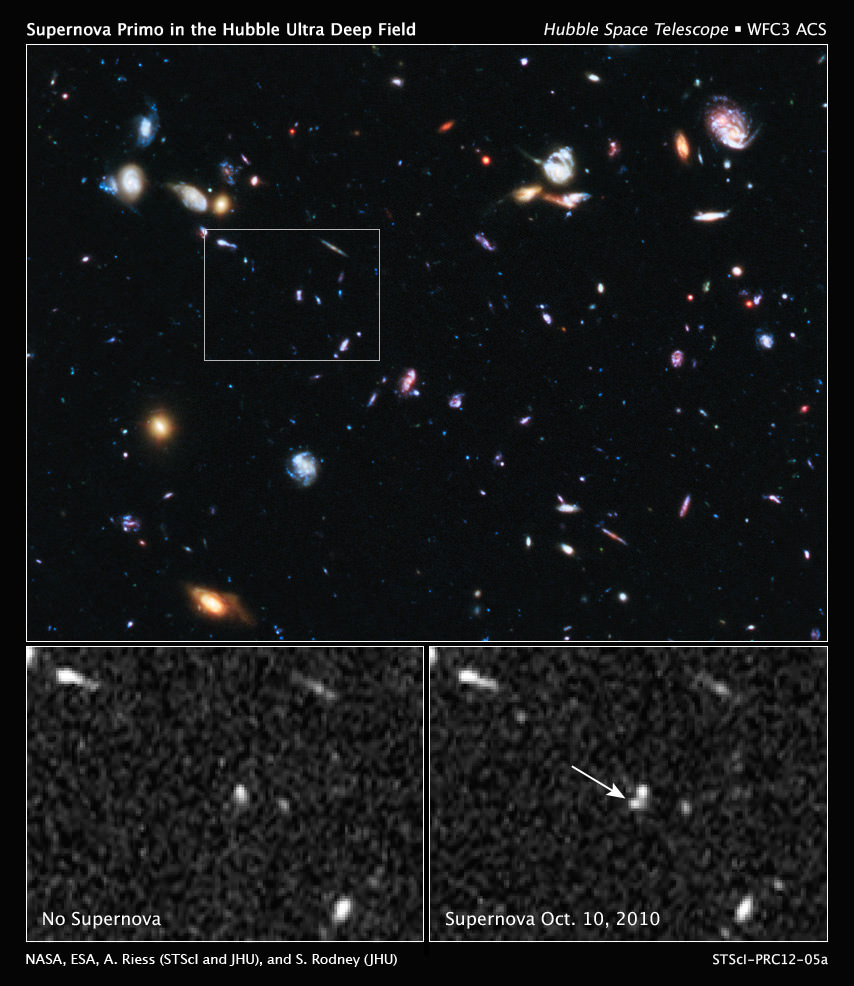

For the next contribution, a jump in scale. To the best of our knowledge, pretty much every galaxy contains a supermassive black hole (SMBH) in its central region. Masses for these SMBHs vary between a hundred thousand times the mass of our Sun and several billion solar masses. Matter falling into such a black hole (and getting caught up, intermittently, in super-hot accretion disks swirling around the SMBHs) is responsible for some of the brightest phenomena in the universe: active galaxies, including ultra high-powered quasars. The contribution of matter caught up in SMBHs to our energy inventory is rather modest, though: about 4 ppm; possibly a bit more.

Who else is playing in the same league? The sum total of all electromagnetic radiation produced by stars and by active galaxies (to name the two most important sources) over the course of the last billions of years, to name one: 2 ppm. Also, neutrinos produced during supernova explosions (at the end of the life of massive stars), or in the formation of white dwarfs (remnants of lower-mass stars like our Sun), or simply as part of the ordinary fusion processes that power ordinary stars: 3.2 ppm all in all.

Then, there’s binding energy: If two components are bound together, you will need to invest energy in order to separate them. That’s why binding energy is negative – it’s an energy deficit you will need to overcome to pry the system’s components apart. Nuclear binding energy, from stars fusing together light elements to form heavier ones, accounts for -6.3 ppm in the present universe – and the total gravitational binding energy accumulated as stars, galaxies, galaxy clusters, other gravitationally bound objects and the large-scale structure of the universe have formed over the past 14 or so billion years, for an even larger -13.4 ppm. All in all, the negative contributions from binding energy more than cancel out all the positive contributions by planets, radiation, neutrinos etc. we’ve listed so far.

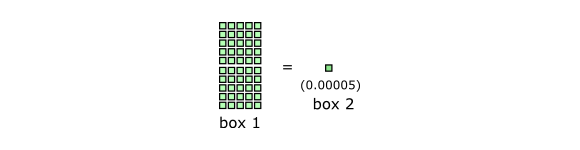

Which brings us to the next level. In order to visualize larger contributions, we need a change scale. In box 2, one square will represent a fraction of 1/20,000 or 0.00005. Put differently: Fifty of the little squares in the first box correspond to a single square in the second box:

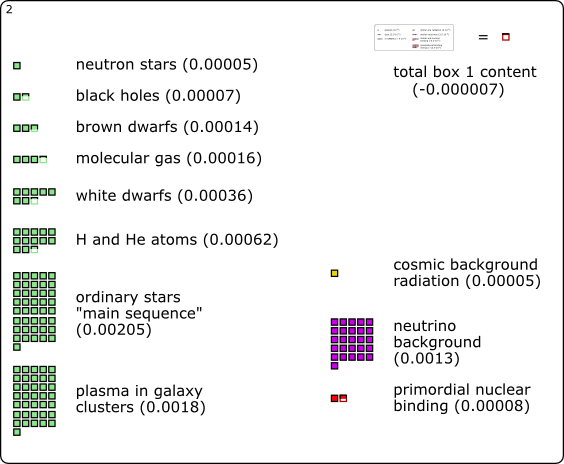

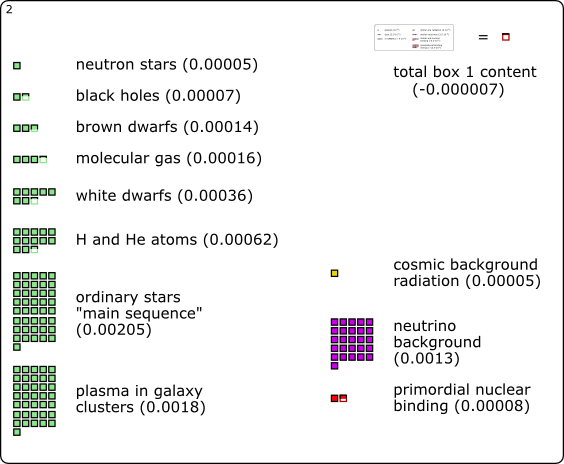

So here, without further ado, is box 2 (including, in the upper right corner, a scale model of the first box):

Now we are in the realm of stars and related objects. By measuring the luminosity of galaxies, and using standard relations between the masses and luminosity of stars (“mass-to-light-ratio”), you can get a first estimate for the total mass (equivalently: energy) contained in stars. You’ll also need to use the empirical relation (“initial mass function”) for how this mass is distributed, though: How many massive stars should there be? How many lower-mass stars? Since different stars have different lifetimes (live massively, die young), this gives estimates for how many stars out there are still in the prime of life (“main sequence stars”) and how many have already died, leaving white dwarfs (from low-mass stars), neutron stars (from more massive stars) or stellar black holes (from even more massive stars) behind. The mass distribution also provides you with an estimate of how much mass there is in substellar objects such as brown dwarfs – objects which never had sufficient mass to make it to stardom in the first place.

Let’s start small with the neutron stars at 0.00005 (1 square, at our current scale) and the stellar black holes (0.00007). Interestingly, those are outweighed by brown dwarfs which, individually, have much less mass, but of which there are, apparently, really a lot (0.00014; this is typical of stellar mass distribution – lots of low-mass stars, much fewer massive ones.) Next come white dwarfs as the remnants of lower-mass stars like our Sun (0.00036). And then, much more than all the remnants or substellar objects combined, ordinary, main sequence stars like our Sun and its higher-mass and (mostly) lower-mass brethren (0.00205).

Interestingly enough, in this box, stars and related objects contribute about as much mass (or energy) as more undifferentiated types of matter: molecular gas (mostly hydrogen molecules, at 0.00016), hydrogen and helium atoms (HI and HeI, 0.00062) and, most notably, the plasma that fills the void between galaxies in large clusters (0.0018) add up to a whopping 0.00258. Stars, brown dwarfs and remnants add up to 0.00267.

Further contributions with about the same order of magnitude are survivors from our universe’s most distant past: The cosmic background radiation (CMB), remnant of the extremely hot radiation interacting with equally hot plasma in the big bang phase, contributes 0.00005; the lesser-known cosmic neutrino background, another remnant of that early equilibrium, contributes a remarkable 0.0013. The binding energy from the first primordial fusion events (formation of light elements within those famous “first three minutes”) gives another contribution in this range: -0.00008.

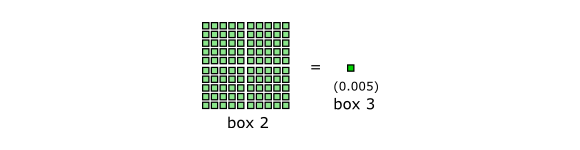

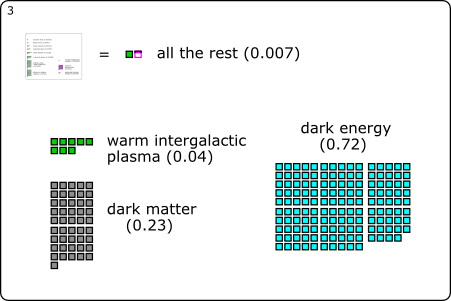

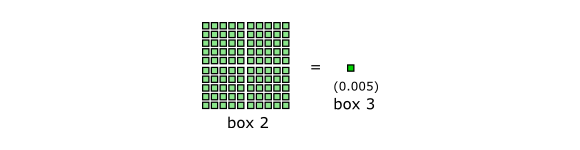

While, in the previous box, the matter we love, know and need was not dominant, it at least made a dent. This changes when we move on to box 3. In this box, one square corresponds to 0.005. In other words: 100 squares from box 2 add up to a single square in box 3:

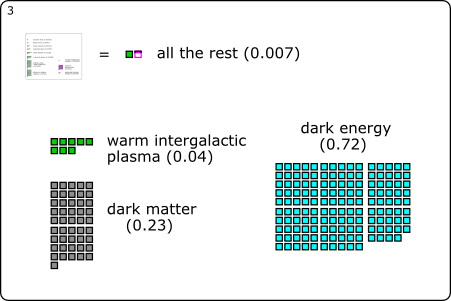

Box 3 is the last box of our chart. Again, a scale model of box 2 is added for comparison: All that’s in box 2 corresponds to one-square-and-a-bit in box 3.

The first new contribution: warm intergalactic plasma. Its presence is deduced from the overall amount of ordinary matter (which follows from measurements of the cosmic background radiation, combined with data from surveys and measurements of the abundances of light elements) as compared with the ordinary matter that has actually been detected (as plasma, stars, e.g.). From models of large-scale structure formation, it follows that this missing matter should come in the shape (non-shape?) of a diffuse plasma, which isn’t dense (or hot) enough to allow for direct detection. This cosmic filler substance amounts to 0.04, or 85% of ordinary matter, showing just how much of a fringe phenomena those astronomical objects we usually hear and read about really are.

The final two (dominant) contributions come as no surprise for anyone keeping up with basic cosmology: dark matter at 23% is, according to simulations, the backbone of cosmic large-scale structure, with ordinary matter no more than icing on the cake. Last but not least, there’s dark energy with its contribution of 72%, responsible both for the cosmos’ accelerated expansion and for the 2011 physics Nobel Prize.

Minority inhabitants of a part-per-million type of object made of non-standard cosmic matter – that’s us. But at the same time, we are a species, that, its cosmic fringe position notwithstanding, has made remarkable strides in unravelling the big picture – including the cosmic inventory represented in this chart.

__________________________________________

Here is the full chart for you to download: the PNG version (1200×900 px, 233 kB) or the lovingly hand-crafted SVG version (29 kB).

The chart “The Cosmic Energy Inventory” is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0. In short: You’re free to use it non-commercially; you must add the proper credit line “Markus Pössel [www.haus-der-astronomie.de]”; if you adapt the work, the result must be available under this or a similar license.

Technical notes: As is common in astrophysics, Fukugita and Peebles give densities as fractions of the so-called critical density; in the usual cosmological models, that density, evaluated at any given time (in this case: the present), is critical for determining the geometry of the universe. Using very precise measurements of the cosmic background radiation, we know that the average density of the universe is indistinguishable from the critical density. For simplicity’s sake, I’m skipping this detour in the main text and quoting all of F & P’s numbers as “fractions of the universe’s total energy (density)”.

For the supermassive black hole contributions, I’ve neglected the fraction ?n in F & P’s article; that’s why I’m quoting a lower limit only. The real number could theoretically be twice the quoted value; it’s apparently more likely to be close to the value given here, though. For my gravitational binding energy, I’ve added F & P’s primeval gravitational binding energy (no. 4 in their list) and their binding energy from dissipative gravitational settling (no. 5).

The fact that the content of box 3 adds up not quite to 1, but to 0.997, is an artefact of rounding not quite consistently when going from box 2 to box 3. I wanted to keep the sum of all that’s in box 2 at the precision level of that box.