The first results from the largest and most complex scientific instrument on board the International Space Station has provided tantalizing hints of nature’s best-kept particle secrets, but a definitive signal for dark matter remains elusive. While the AMS has spotted millions of particles of antimatter – with an anomalous spike in positrons — the researchers can’t yet rule out other explanations, such as nearby pulsars.

“These observations show the existence of new physical phenomena,” said AMS principal investigator Samuel Ting,” and whether from a particle physics or astrophysical origin requires more data. Over the coming months, AMS will be able to tell us conclusively whether these positrons are a signal for dark matter, or whether they have some other origin.”

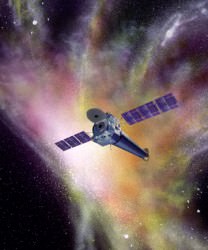

The AMS was brought to the ISS in 2011 during the final flight of space shuttle Endeavour, the penultimate shuttle flight. The $2 billion experiment examines ten thousand cosmic-ray hits every minute, searching for clues into the fundamental nature of matter.

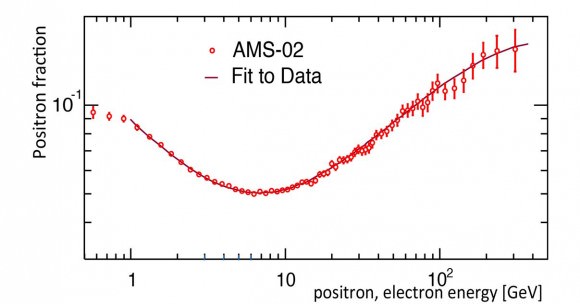

During the first 18 months of operation, the AMS collected of 25 billion events. It found an anomalous excess of positrons in the cosmic ray flux — 6.8 million are electrons or their antimatter counterpart, positrons.

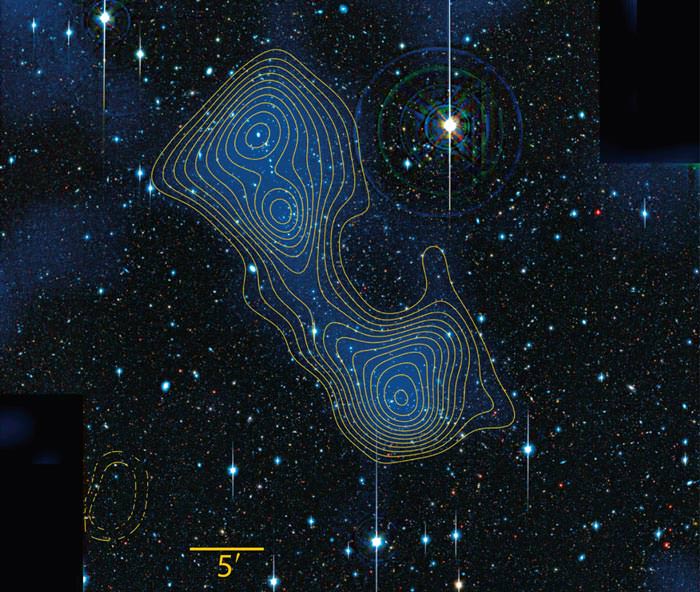

The AMS found the ratio of positrons to electrons goes up at energies between 10 and 350 gigaelectronvolts, but Ting and his team said the rise is not sharp enough to conclusively attribute it to dark matter collisions. But they also found that the signal looks the same across all space, which would be expected if the signal was due to dark matter – the mysterious stuff that is thought to hold galaxies together and give the Universe its structure.

Additionally, the energies of these positrons suggest they might have been created when particles of dark matter collided and destroyed each other.

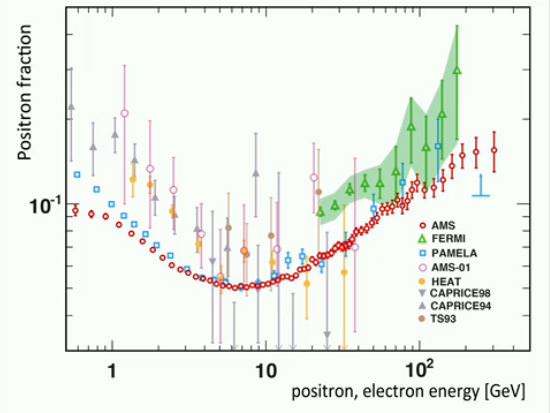

The AMS results are consistent with the findings of previous telescopes, like the Fermi and PAMELA gamma-ray instruments, which also saw a similar rise, but Ting said the AMS results are more precise.

The results released today do not include the last 3 months of data, which have not yet been processed.

“As the most precise measurement of the cosmic ray positron flux to date, these results show clearly the power and capabilities of the AMS detector,” Ting said.

Cosmic rays are charged high-energy particles that permeate space. An excess of antimatter within the cosmic ray flux was first observed around two decades ago. The origin of the excess, however, remains unexplained. One possibility, predicted by a theory known as supersymmetry, is that positrons could be produced when two particles of dark matter collide and annihilate. Ting said that over the coming years, AMS will further refine the measurement’s precision, and clarify the behavior of the positron fraction at energies above 250 GeV.

Although having the AMS in space and away from Earth’s atmosphere – allowing the instruments to receive a constant barrage of high-energy particles — during the press briefing, Ting explained the difficulties of operating the AMS in space. “You can’t send a student to go out and fix it,” he quipped, but also added that the ISS’s solar arrays and the departure and arrival of the various spacecraft can have an effect on thermal fluctuations the sensitive equipment might detect. “You need to monitor and correct the data constantly or you are not getting accurate results,” he said.

Despite recording over 30 billion cosmic rays since AMS-2 was installed on the International Space Station in 2011, the Ting said the findings released today are based on only 10% of the readings the instrument will deliver over its lifetime.

Asked how much time he needs to explore the anomalous readings, Ting just said, “Slowly.” However, Ting will reportedly provide an update in July at the International Cosmic Ray Conference.

More info: CERN press release, the team’s paper: First Result from the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer on the International Space Station: Precision Measurement of the Positron Fraction in Primary Cosmic Rays of 0.5–350 GeV