[/caption]

We’re still mostly in the dark about Dark Matter, and the highly anticipated results from the XENON100 detector has perhaps shed a tad more light on the subject – by not making a detection in the first 100 days of the experiment. Researchers from the project say they have now been able to place the most stringent limits yet on the properties of dark matter.

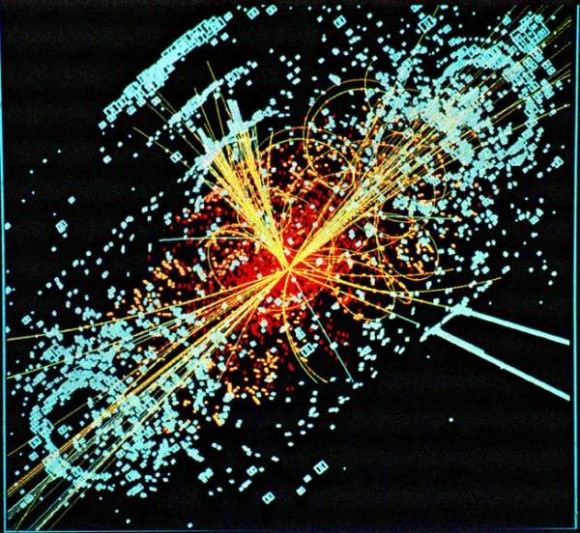

To look for any possible hints of Dark Matter interacting with ordinary matter, the project has been looking for WIMPS — or weakly interacting massive particles – but for now, there is no new evidence for the existence of WIMPS, or Dark Matter either.

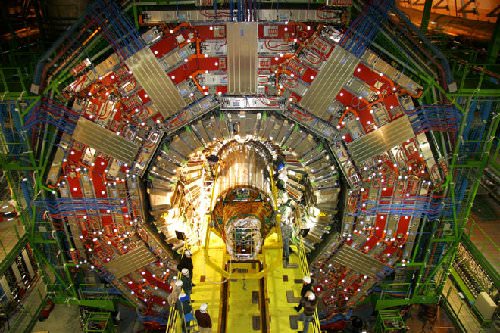

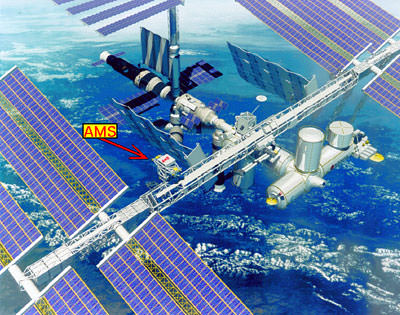

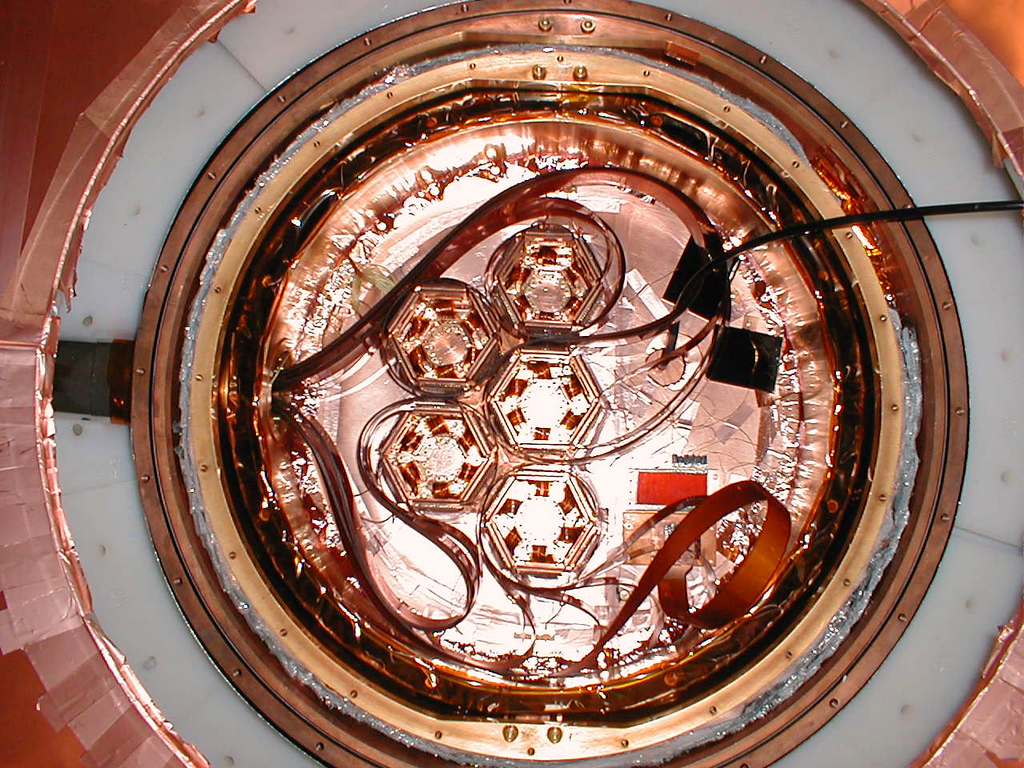

The extremely sensitive XENON100 detector is buried beneath the Gran Sasso mountain in central Italy, shielding it from cosmic radiation so it hopefully can detect WIMPS, hypothetical particles that might be heavier than atomic nuclei, and the most popular candidate for what Dark Matter might be made of. The detector consists of 62 kg of liquid xenon contained within a heavily shielded tank. If a WIMP would enter the detector, it should interact with the xenon nuclei to generate light and electric signals – which would be a kind of “You Have Won!” indicator.

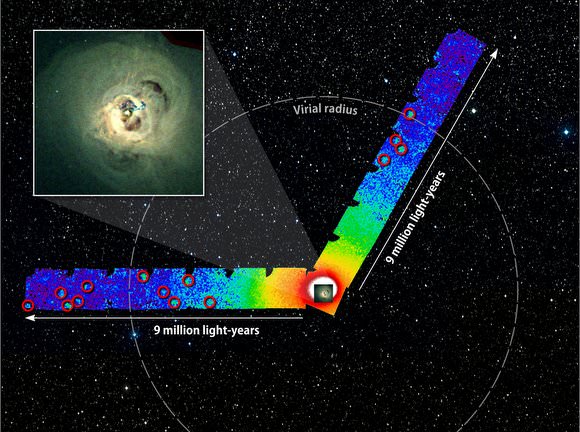

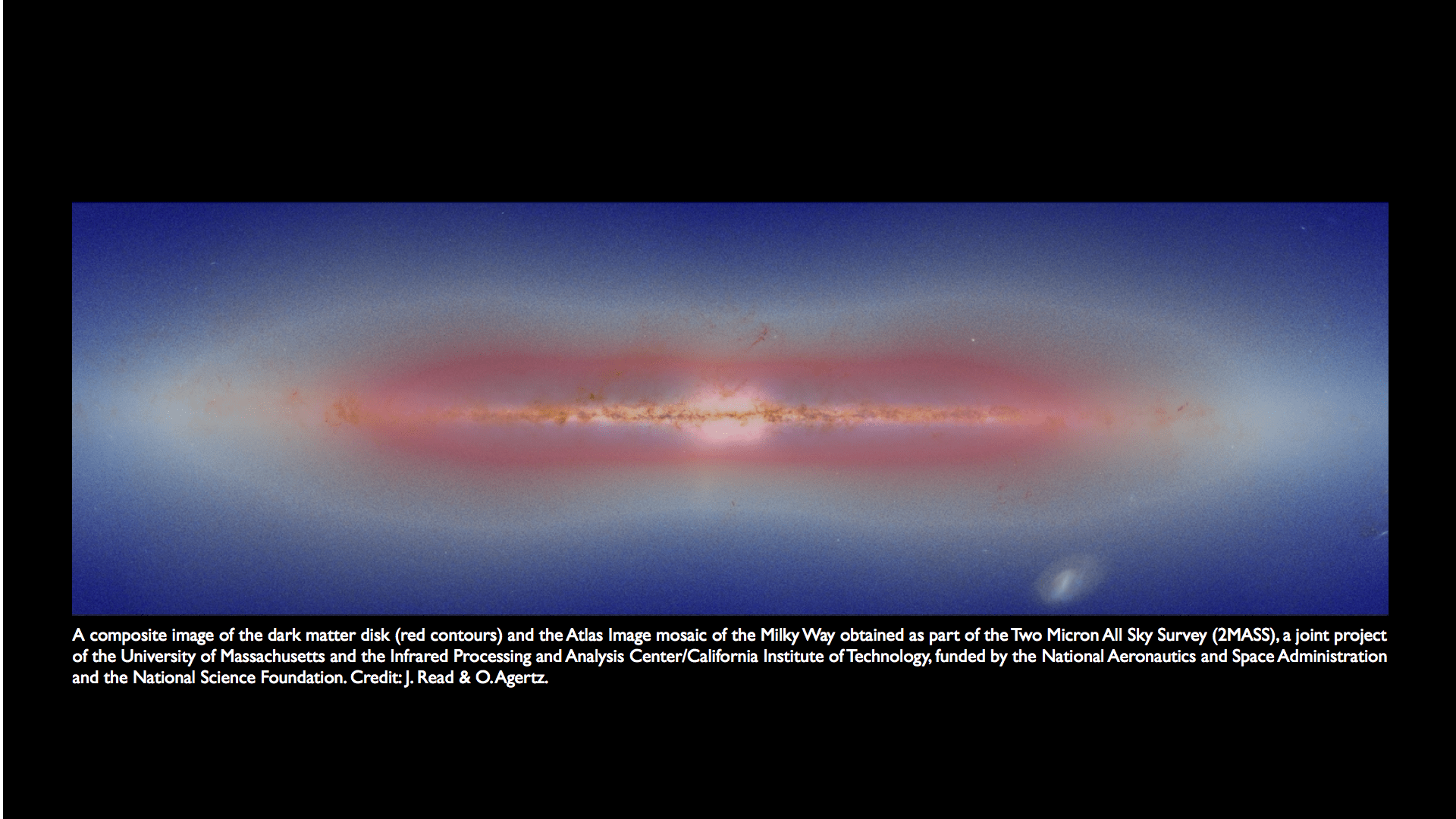

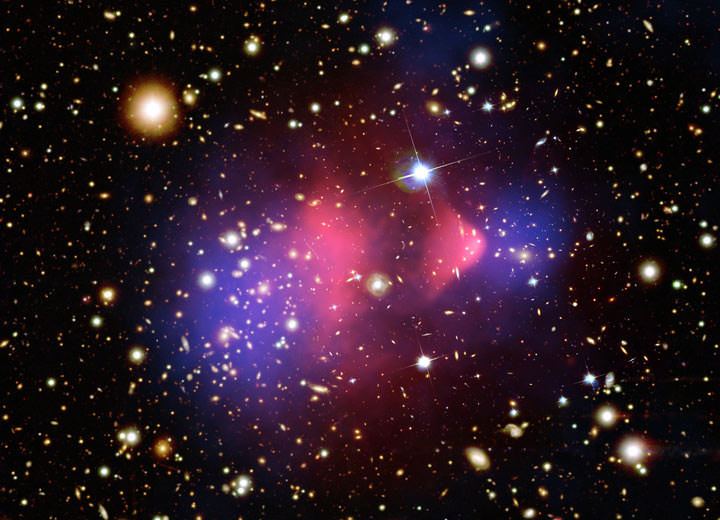

Dark Matter is thought to make up more than 80% of all mass in the universe, but the nature of it is still unknown. Scientists believe that it is made up of exotic particles unlike the normal (baryonic) matter, which we, the Earth, Sun and stars are made of, and it is invisible so it has only been inferred from its gravitational effects.

The XENON detector ran from January to June 2010 for its first run, and in their paper on arxiv, the team revealed they found three candidate events that might be due to Dark Matter. But two of these were expected to appear anyway because of background noise, the team said, so their results are effectively negative.

Does this rule out the existence of WIMPS? Not necessarily – the team will keep working on their search. Plus, results from a preliminary analysis from11.2 days worth of data, taken during the experiment’s commissioning phase in October and November 2009, already set new upper limits on the interaction rate of WIMPs – the world’s best for WIMP masses below about 80 times the mass of a proton.

And the XENON100 team was optimistic. “These new results reveal the highest sensitivity reported as yet by any dark matter experiment, while placing the strongest constraints on new physics models for particles of dark matter,” the team said in a statement.

Sources: EurekAlert, physicsworld