[/caption]

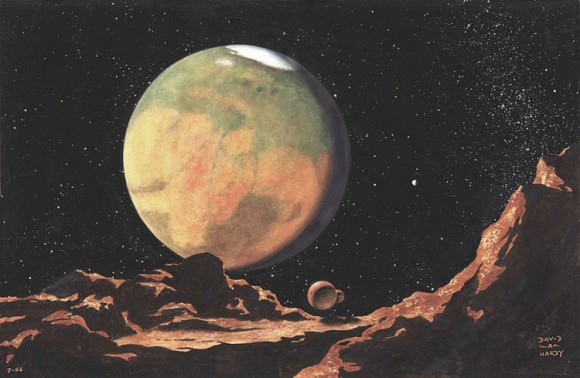

For over 50 years, award-winning space and astronomy artist David A. Hardy has taken us to places we could only dream of visiting. His career started before the first planetary probes blasted off from Earth to travel to destinations in our solar system and before space telescopes viewed distant places in our Universe. It is striking to view his early work and to see how accurately he depicted distant vistas and landscapes, and surely, his paintings of orbiting space stations and bases on the Moon and Mars have inspired generations of hopeful space travelers.

Hardy published his first work in 1952 when he was just 15. He has since illustrated and produced covers for dozens of science and science fiction books and magazines. He has written and illustrated his own books and has worked with astronomy and space legends like Patrick Moore, Arthur C. Clarke, Carl Sagan, Wernher von Braun, and Isaac Asimov. His work has been exhibited around the world, including at the National Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C. which houses two of his paintings.

Universe Today is proud to announce that Hardy has helped us update the banner at the top of our website (originally designed by Christopher Sisk) to make it more astronomically accurate.

Hardy has also recently debuted his own new website where visitors can peruse and learn more about his work, and buy prints and other items.

We had the chance to talk with Hardy about his enduring space art and career:

Universe Today: When you first started your space art, there weren’t images from Voyager, Cassini, Hubble, etc. to give you ideas for planetary surfaces and colored space views. What was your inspiration?

David Hardy: I got to look through a telescope when I was about 16. You only have to see the long shadows creeping across a lunar crater to know that this is a world. But I also found the book ‘The Conquest of Space‘ in my local library, and Chesley Bonestell’s photographic paintings of the Moon and planets just blew me away! I knew that I wanted to produce pictures that would show people what it’s really like out there — not just as rather blurry discs of light through a telescope.

UT: And now that we have such spacecraft sending back amazing images, how has that changed your art, or how have the space images inspired you?

Hardy: I was lucky to start when I did, because in 1957 we had Sputnik, and then the exploration of space really started. We started getting photos of the Earth from space, and of the Moon from probes and orbiters, then of Mars, and eventually from the outer planets. Each of these made it possible to produce better and more realistic and accurate paintings of these worlds.

UT: We are amazed at your early work — you were so young and doing such amazing space art! How does it feel to have inspired several generations of people? — Surely your art has driven many to say, “I want to go there!”

Hardy: I certainly hope so — that was the idea! In 1954 I met the astronomer Patrick Moore, who asked me to illustrate a new book in 1954, and we have continued to work together until the present day. Back then we wanted to so a sort of British version of The Conquest of Space, which we called ‘The Challenge of the Stars.’ In the 1950s we couldn’t find a publisher — they all said it was ‘too speculative!’ But a book with that title was published in 1972; ironically (and unbelievably), just when humans visited the Moon for the last time. We had hoped that the first Moon-landings would lead to a base, and that we would go on to Mars, but for all sorts of reasons (mainly political) this never happened. In 2004 Patrick and I produced a book called ‘Futures: 50 Years in Space,’ celebrating our 50 years together. It was subtitled: ‘The Challenge of the Stars: What we thought then –What we know now.’

I quite often find that younger space artists tell me they were influenced by The Challenge of the Stars, just as I was influenced by The Conquest of Space, and this is a great honour.

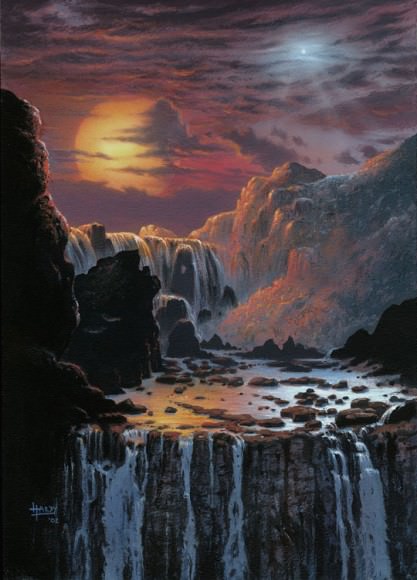

UT: What places on Earth have most inspired your art?

Hardy: I’m a past President (and now European VP) of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA; www.iaaa.org), and we hold workshops in the most ‘alien’ parts of Planet Earth. Through these I have been to the volcanoes of Hawaii and Iceland, to Death Valley CA, the Grand Canyon and Meteor Crater, AZ, to Nicaragua. . . all of these provide not just inspiration but analogues of other worlds like Mars, Io or Triton, so that we can make our work more believable and authentic — as well as more beautiful, hopefully.

UT: How has technology changed how you do your work?

Hardy: I have always kept up with new technology, making use of xeroxes, photography (I used to do all my own darkroom work and processing), and most recently computers. I got an Atari ST with 512k (yes, K!) of RAM in 1986, and my first Mac in 1991. I use Photoshop daily, but I use hardly any 3D techniques, apart from Terragen to produce basic landscapes and Poser for figures. I do feel that 3D digital techniques can make art more impersonal; it can be difficult or impossible to know who created it! And I still enjoy painting in acrylics, especially large works on which I can use ‘impasto’ –laying on paint thickly with a palette knife and introducing textures that cannot be produced digitally!

UT: Your new website is a joy to peruse — how does technology/the internet help you to share your work?

Hardy: Thank you. It is hard now to remember how we used to work when we were limited to sending work by mail, or faxing sketches and so on. The ability to send first a low-res jpeg for approval, and then a high-res one to appear in a book or on a magazine cover, is one of the main advantages, and indeed great joys, of this new technology.

UT: I imagine an artist as a person working alone. However, you are part of a group of artists and are involved heavily in the Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists. How helpful is it to have associations with fellow artists?

Hardy: It is true that until 1988, when I met other IAAA artists (both US, Canadian and, then, Soviet, including cosmonaut Alexei Leonov) in Iceland I had considered myself something of a lone wolf. So it was almost like ‘coming out of the closet’ to meet other artists who were on the same wavelength, and could exchange notes, hints and tips.

UT: Do you have a favorite image that you’ve created?

Hardy: Usually the last! Which in this case is a commission for a metre-wide painting on canvas called ‘Ice Moon’. I put this on Facebook, where it has received around 100 comments and ‘likes’ — all favourable, I’m glad to say. It can be seen there on my page, or on my own website, www.astroart.org (UT note: this is a painting in acrylics on stretched canvas, with the description,”A blue ice moon of a gas giant, with a derelict spaceship which shouldn’t look like a spaceship at first glance.”)

UT: Anything else you feel is important for people to know about your work?

Hardy: I do feel that it’s quite important for people to understand the difference between astronomical or space art, and SF (‘sci-fi’) or fantasy art. The latter can use a lot more imagination, but often contains very little science — and often gets it quite wrong. I also produce a lot of SF work, which can be seen on my site, and have done around 70 covers for ‘The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’ since 1971, and many for ‘Analog’. I’m Vice President of the Association of Science Fiction & Fantasy Artists (ASFA; www.asfa-art.org ) too. But I always make sure that my science is right! I would also like to see space art more widely accepted in art galleries, and in the Art world in general; we do tend to feel marginalised.

UT: Thank you for providing Universe Today with a more “accurate” banner — we really appreciate your contribution to our site!

Hardy: My pleasure.

See more at Hardy’s website, AstroArt or his Facebook page. Click on any of the images here to go directly to Hardy’s website for more information on each.

Here’s a list of the books Hardy has written and/or illustrated.