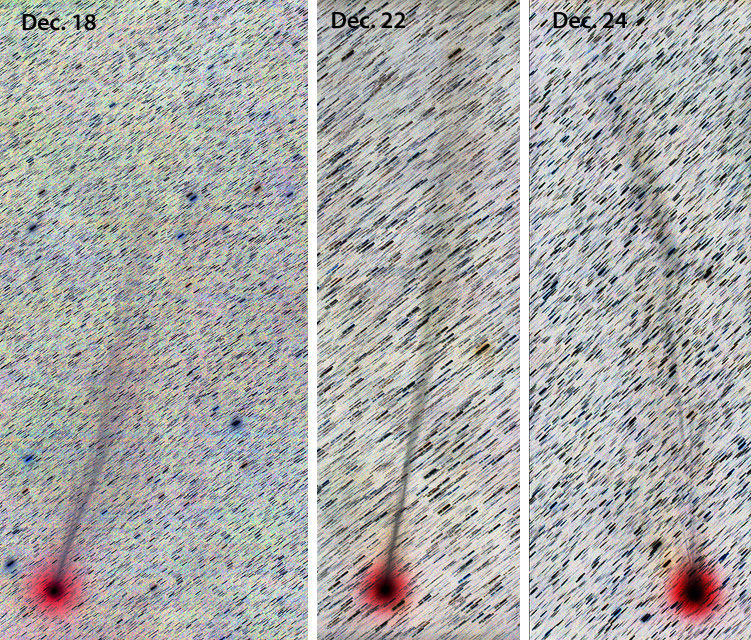

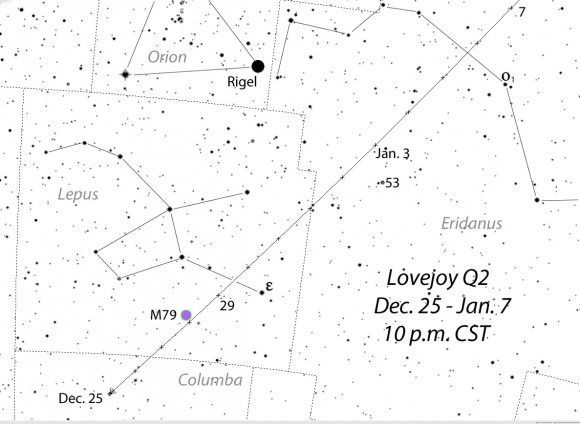

Maybe you’ve seen Comet Q2 Lovejoy. It’s a big fuzzy ball in binoculars low in the southern sky in the little constellation Lepus the Hare. That’s the comet’s coma or temporary atmosphere of dust and gas that forms when ice vaporizes in sunlight from the nucleus. Until recently a faint 3° ion or gas tail trailed in the coma’s wake, but on and around December 23rd it snapped off and was ferried away by the solar wind. Just as quickly, Lovejoy re-grew a new ion tail but can’t seem to hold onto that one either. Like a feather in the wind, it’s in the process of being whisked away today.

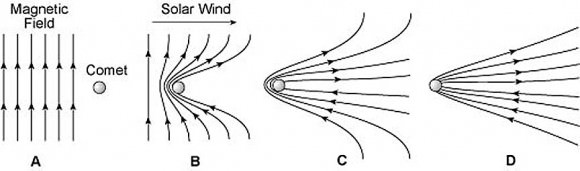

Easy come, easy go. Comets usually have two tails, one of dust particles that reflect sunlight and another of ionized gases that fluoresce in Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Ion tails form when cometary gases, primarily carbon monoxide, are ionized by solar radiation and lose an electron to become positively charged. Once “electrified”, they’re susceptible to magnetic fields embedded in the high-speed stream of charged particles flowing from the Sun called the solar wind. Magnetic field lines embedded in the wind drape around the comet and draw the ions into a long, skinny tail directly opposite the Sun.

Disconnection events happen when fluctuations in the solar wind cause oppositely directed magnetic fields to reconnect in explosive fashion and release energy that severs the tail. Set free, it drifts away from the comet and dissipates. In active comets, the nucleus continues to produce gases, which in turn are ionized by the Sun and drawn out into a replacement appendage. In one of those delightful coincidences, comets and geckos both share the ability to re-grow a lost tail.

Comet Encke tail disconnection April 20, 2007 as seen by STEREO

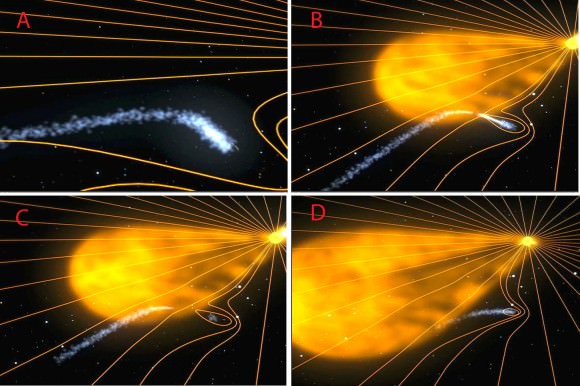

Comet Halley experienced two ion tail disconnection events in 1986, but one of the most dramatic was recorded by NASA’s STEREO spacecraft on April 20, 2007. A powerful coronal mass ejection (CME) blew by comet 2P/Encke that spring day wreaking havoc with its tail. Magnetic field lines from the plasma blast reconnected with opposite polarity magnetic fields draped around the comet much like when the north and south poles of two magnets snap together. The result? A burst of energy that sent the tail flying.

Comet Lovejoy may have also crossed a sector boundary where the magnetic field carried across the Solar System by Sun’s constant breeze changed direction from south to north or north to south, opposite the magnetic domain the comet was immersed in before the crossing. Whether solar wind flutters, coronal mass ejections or sector boundary crossings, more tail budding likely lies in Lovejoy’s future. Like the chard in your garden that continues to sprout after repeated snipping, the comet seems poised to spring new tails on demand.

If you haven’t seen the comet, it’s now glowing at magnitude +5.5 and faintly visible to the naked eye from a dark sky site. Without an obvious dust tail and sporting a faint ion tail(s), the comet’s basically a giant coma, a fuzzy glowing ball easily visible in a pair of binoculars or small telescope.

In a very real sense, Comet Lovejoy experienced a space weather event much like what happens when a CME compresses Earth’s magnetic field causing field lines of opposite polarity to reconnect on the back or nightside of the planet. The energy released sends millions of electrons and protons cascading down into our upper atmosphere where they stimulate molecules of oxygen and nitrogen to glow and produce the aurora. One wonders whether comets might even experience their own brief auroral displays.

Excellent visualization showing how magnetic fields line on Earth’s nightside reconnect to create the rain of electrons that cause the aurora borealis. Notice the similarity to comet tail loss.