In ancient times, the scholars, seers and magi of various cultures believed that the world took a number of forms – ranging from a ziggurat or a cube to the more popular flat disc surrounded by a sea. But thanks to the ongoing efforts of astronomers, we have come to understand that it is in fact a sphere, and one of many planets in a system that orbits the Sun.

Within the past few centuries, improvements in both scientific instruments and more comprehensive observations of the heavens have also helped astronomers to determine (with extreme accuracy) what the nature of Earth’s orbit is. In addition to knowing the precise distance from the Sun, we also know that our planet orbits the Sun with one pole constantly tilted towards it.

Earth’s Axis:

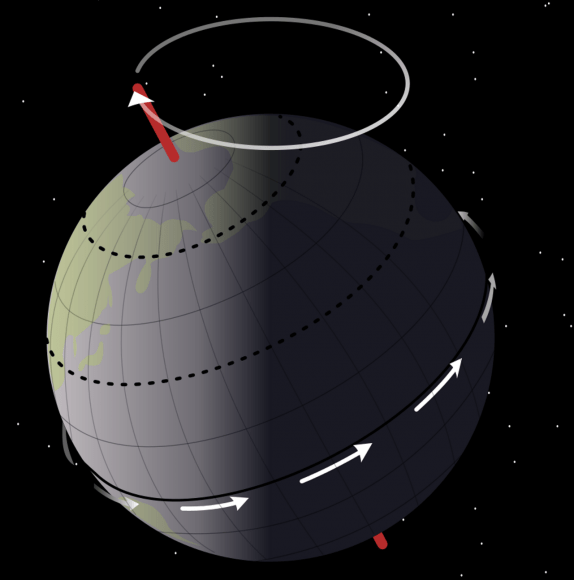

This is what is known axial tilt, where a planet’s vertical axis is tilted a certain degree towards the ecliptic of the object it orbits (in this case, the Sun). Such a tilt results in there being a difference in how much sunlight reaches a given point on the surface during the course of a year. In the case of Earth, the axis is tilted towards the ecliptic of the Sun at approximately 23.44° (or 23.439281° to be exact).

Seasonal Variations:

This tilt in Earth’s axis is what is responsible for seasonal changes during the course of the year. When the North Pole is pointed towards the Sun, the northern hemisphere experiences summer and the southern hemisphere experiences winter. When the South Pole is pointed towards the Sun, six months later, the situation is reversed.

In addition to variations in temperature, seasonal changes also result in changes to the diurnal cycle. Basically, in the summer, the day last longer and the Sun climbs higher in the sky. In winter, the days become shorter and the Sun is lower in the sky. In northern temperate latitudes, the Sun rises north of true east during the summer solstice, and sets north of true west, reversing in the winter. The Sun rises south of true east in the summer for the southern temperate zone, and sets south of true west.

The situation becomes extreme above the Arctic Circle, where there is no daylight at all for part of the year, and for up to six months at the North Pole itself (known as a “polar night”). In the southern hemisphere, the situation is reversed, with the South Pole oriented opposite the direction of the North Pole and experiencing what is known as a “midnight sun” (a day that lasts 24 hours).

The four seasons can be determined by the solstices (the point of maximum axial tilt toward or away from the Sun) and the equinoxes (when the direction of tilt and the Sun are perpendicular). In the northern hemisphere, winter solstice occurs around December 21st, summer solstice around June 21st, spring equinox around March 20th, and autumnal equinox on or about September 22nd or 23rd. In the southern hemisphere, the situation is reversed, with the summer and winter solstices exchanged and the spring and autumnal equinox dates swapped.

Changes Over Time:

The angle of the Earth’s tilt is relatively stable over long periods of time. However, Earth’s axis does undergo a slight irregular motion known as nutation – a rocking, swaying, or nodding motion (like a gyroscope) – that has a period of 18.6 years. Earth’s axis is also subject to a slight wobble (like a spinning top), which is causing its orientation to change over time.

Known as precession, this process is causing the date of the seasons to slowly change over a 25,800 year cycle. Precession is not only the reason for the difference between a sidereal year and a tropical year, it is also the reason why the seasons will eventually flip. When this happens, summer will occur in the northern hemisphere during December and winter during June.

Precession, along with other orbital factors, is also the reason for what is known as “length-of-day variation”. Essentially, this is a phenomna where the dates of Earth’s perihelion and aphelion (which currently take place on Jan. 3rd and July 4th, respectively) change over time. Both of these motions are caused by the varying attraction of the Sun and the Moon on the Earth’s equatorial region.

Needless to say, Earth’s rotation and orbit around the Sun are not as simple we once though. During the Scientific Revolution, it was a huge revelation to learn that the Earth was not a fixed point in the Universe, and that the “celestial spheres” were planets like Earth. But even then, astronomers like Copernicus and Galileo still believed that the Earth’s orbit was a perfect circle, and could not imagine that its rotation was subject to imperfections.

It’s only been with time that the true nature of our planet’s inclination and movements have come to be understood. And what we know is that they lead to some serious variations over time – both in the short run (i.e. seasonal change), and in the long-run.

We’ve written many articles about the Earth and the seasons for Universe Today. Here’s Why is the Earth Tilted?, The Rotation of the Earth, What Causes Day and Night?, How Fast Does the Earth Rotate?, Why Does the Earth Spin?

If you’d like more information on the Earth’s axis, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide on Earth. And here’s a link to NASA’s Earth Observatory.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast all about Earth. Listen here, Episode 51: Earth.