On September 8th, 2016, NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission was launched into space. In the coming months, this space probe will approach and then rendezvous with the asteroid 101955 Bennu – a Near-Earth Object (NEO) – for the sake of studying it. The mission will also acquire samples of the asteroid, which will be returned to Earth by 2023.

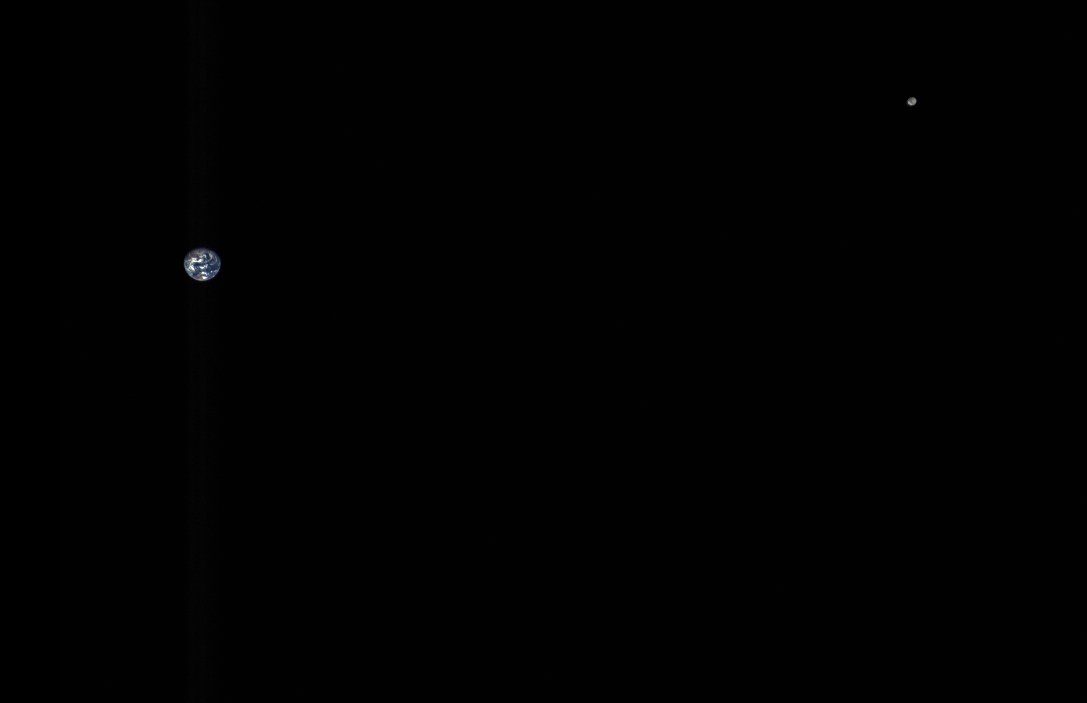

The OSIRIS-REx mission is an historic one, since it will be the first US spacecraft to conduct a sample-return mission with an asteroid. In the meantime, as the probe has makes its way further into space, it has been providing some truly breathtaking images of the journey. Consider the recently-released composite image of the Earth-Moon system, which NASA created using images that were taken by the probe on October 2nd, 2017.

The images were all taken by the probe’s MapCam instrument, a medium-range camera designed to capture images of outgassing around Bennu and help map its surface in color. On this occasion, it snapped three beautiful pictures of Earth and the Moon. These images were all taken when the spacecraft was at a distance of approximately 5 million km (3 million mi) from Earth – about 13 times the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

As part of the OSIRIS-REx Camera Suite (OCAMS), which is operated by researchers at the University of Arizona, the CapCam has four color filters. To produce the image, three of them (b, v and w) were used as a blue, green and red filters and then stacked on top of each other. The Earth and Moon were each color-corrected, and the Moon was brightened to make it more easily visible.

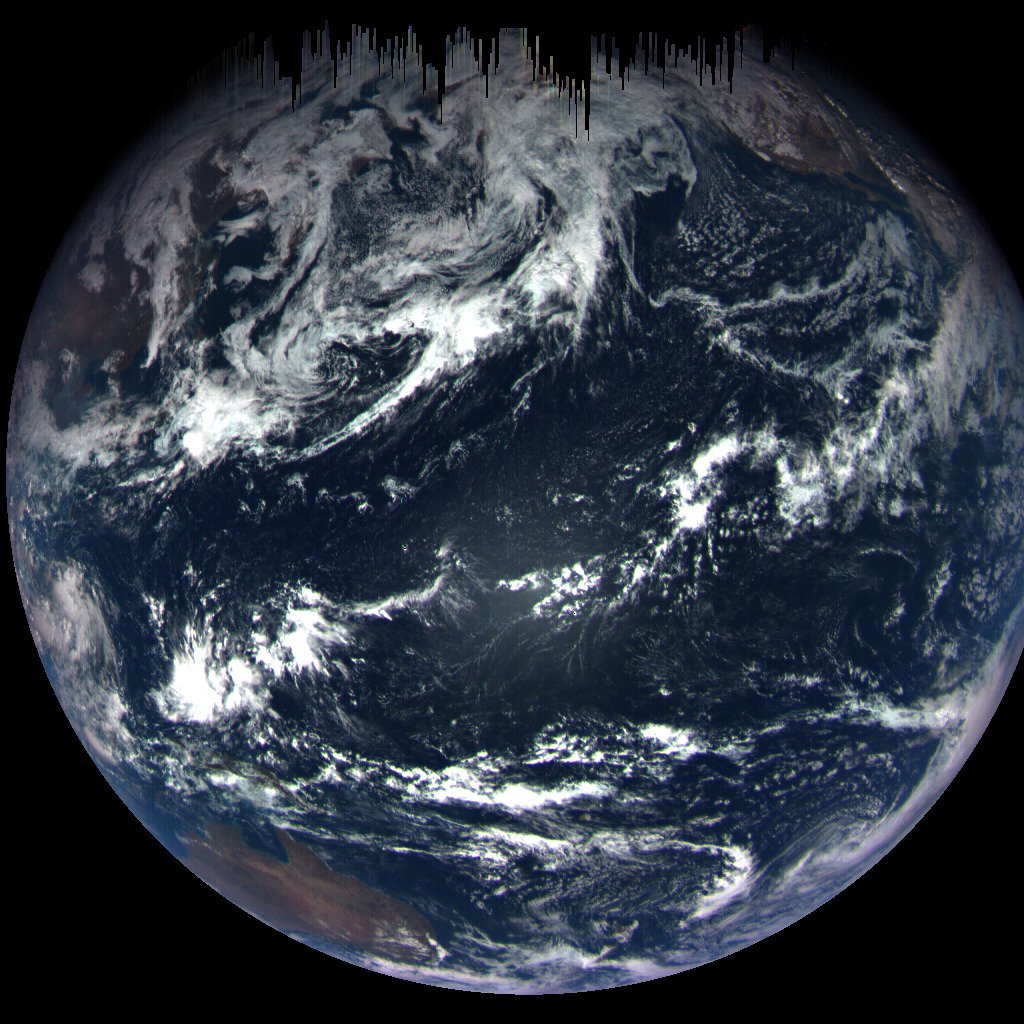

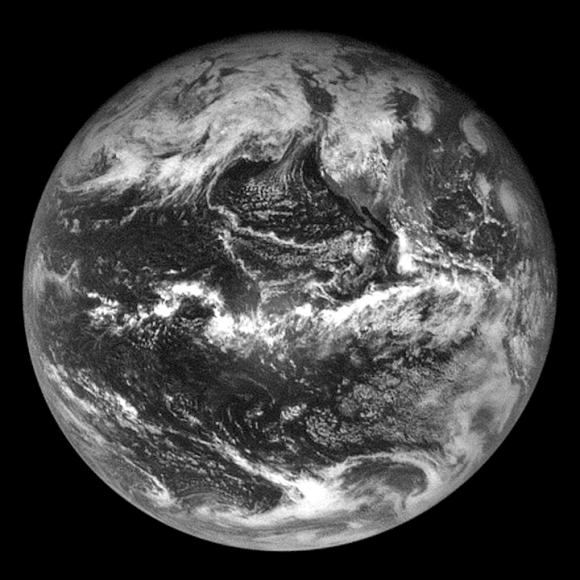

A second image of planet Earth (shown above), was taken on September 22nd, 2017, by one of the probe’s navigational cameras (NavCam 1). As the name suggests, this instrument is intended to help OSIRIS-REx orient itself while making its journey to Bennu and while it studies the asteroid. This is done by tracking starfields in space (while in transit) and landmarks on Bennu’s surface once it has arrived.

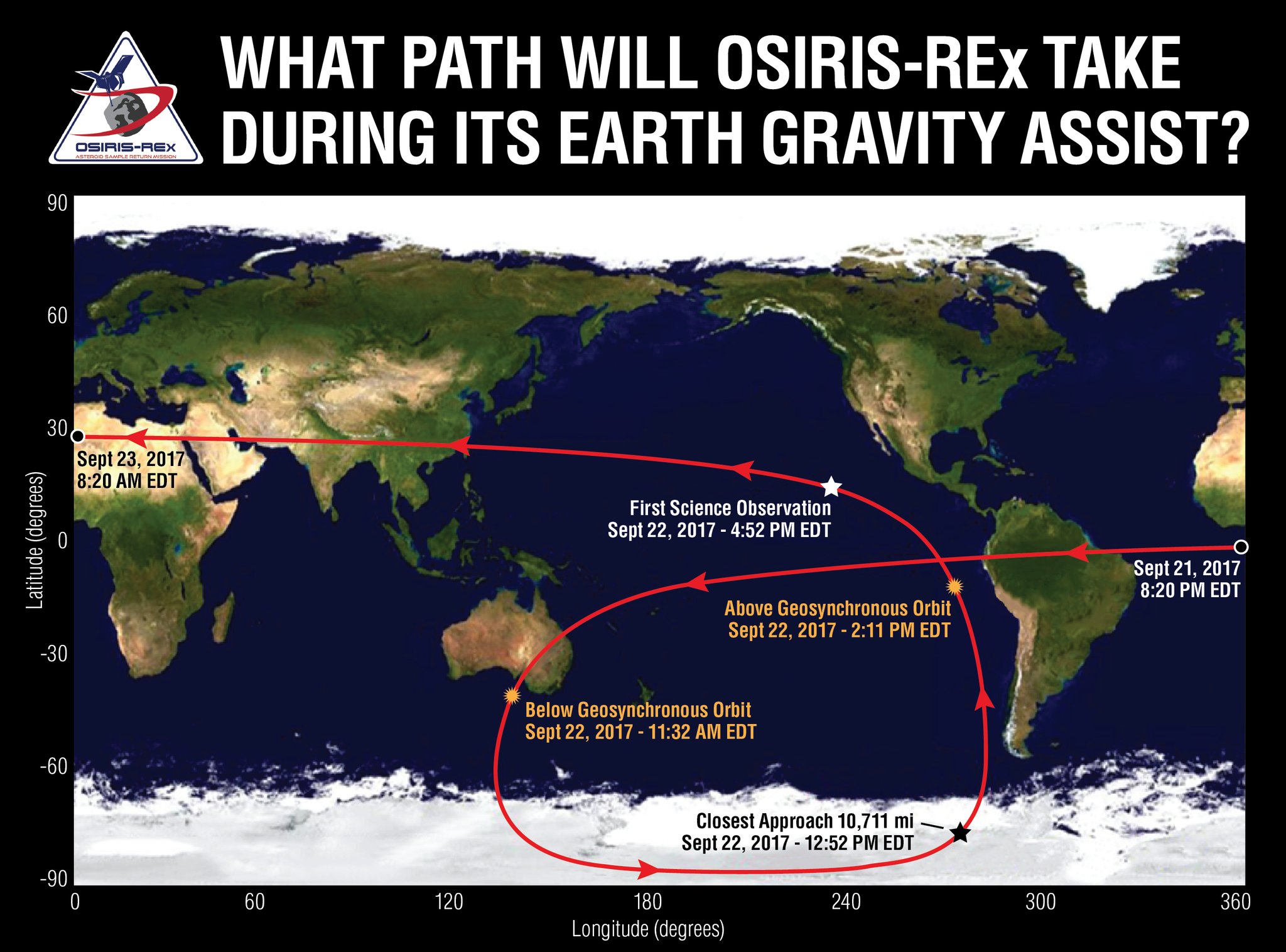

The image was taken when OSIRIS-REx was at a distance of 110,000 km (69,000 mi) from Earth. This was just after the probe had completed an Earth gravity-assist maneuver, where it used Earth’s gravitational force to slingshot around its equator and pick up more speed. The original image (shown below) was rotated so that the North Pole would be pointed up and the entire image was enlarged to provide more detail.

As you can see in the altered image, North America is visible on the upper right portion, while Hurricane Maria and the remnants of Hurricane Jose are visible in the far upper-right. The acquisition of these images was the result of painstaking calculations and planning, which were performed in advance by engineers and navigation specialists on the mission team using software called Systems Tool Kit (STK).

These plans were developed to ensure that the probe would be able to snap pictures with precise timing, which were then uploaded to the spacecraft’s computer weeks ahead of time. Within hours of the probe executing its gravity-assist maneuver, crews on the ground were treated to the first images from the spacecraft’s navigational cameras, which confirmed that the probe was following the right path.

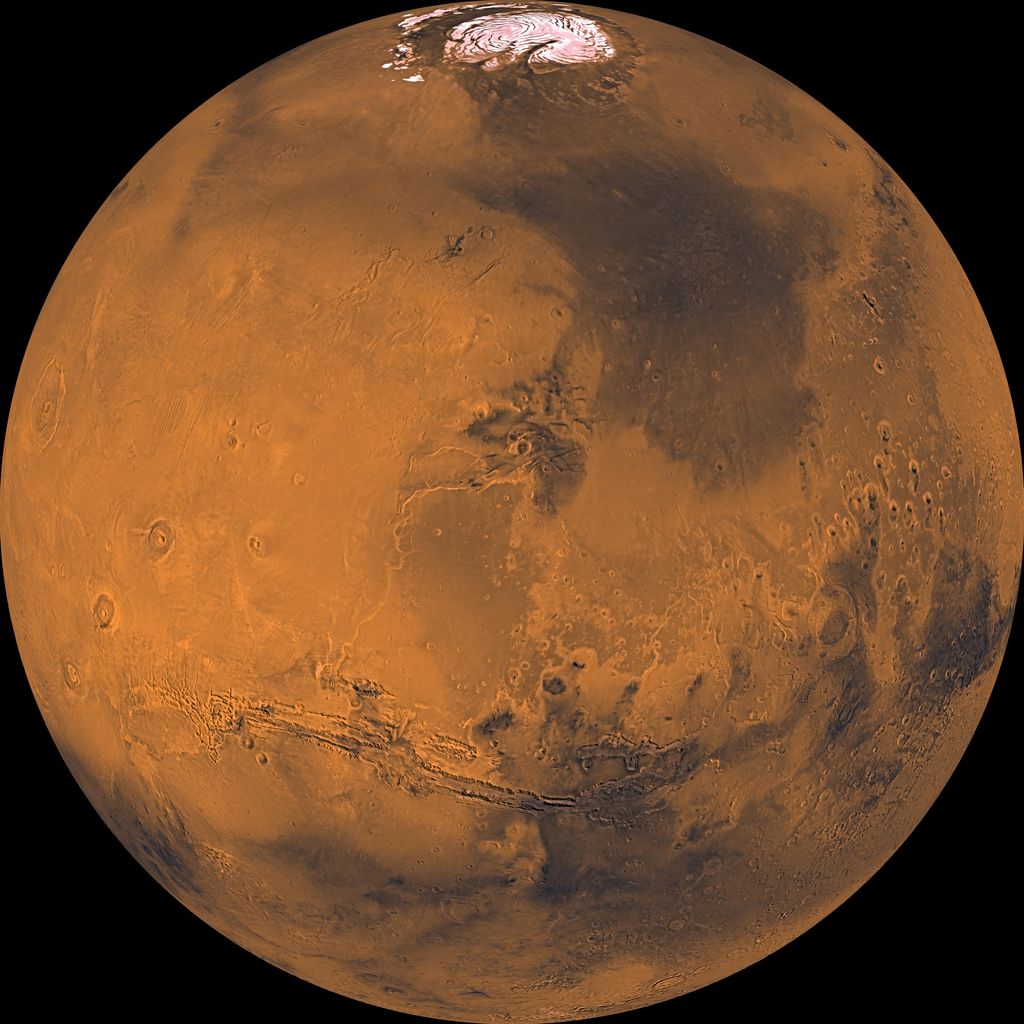

The probe is scheduled to reach Bennu in December of 2018, with approach operations commencing this coming August. Bennu is also expected to make a close pass with Earth several centuries from now, and could even collide with us by then. But for the time being, it represents a major opportunity to study the history and evolution of the Solar System, since it is essentially a remnant left over from its formation.

By studying this asteroid up close, and bringing samples back to Earth for further study, the OSRIS-REx mission could help us understand how life began on Earth and where the Solar System as a whole is headed. But in the meantime, the probe has been able to provide us with some beautiful snapshots of Earth, which serve to remind us all of certain things.

Much like Voyager 1‘s “Pale Blue Dot” photo, seeing Earth from space helps to drive home the fact that life is rare and precious. It also reminds us that we, as a species, are all in this together and completely and utterly dependent on our planet and its ecosystems. Once in awhile, we need to be reminded of these things. Otherwise, we might do some stupid – like ruin it!

Further Reading: NASA